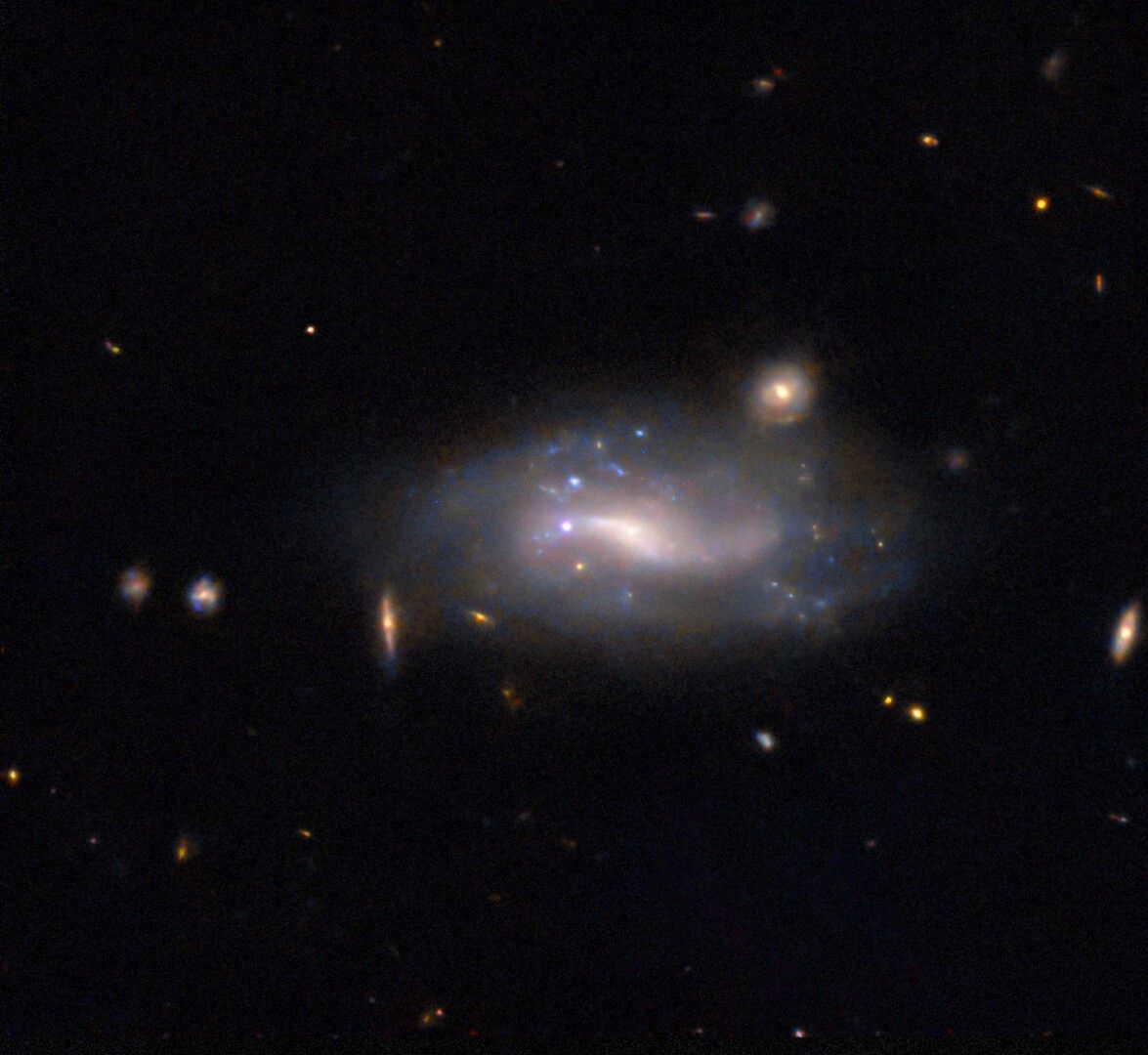

Scientists analyzing the first data from the Neutron star Interior Composition Explorer (NICER) mission have found two stars that revolve around each other every 38 minutes — about the time it takes to stream a TV drama. One of the stars in the system, called IGR J17062–6143 (J17062 for short), is a rapidly spinning, superdense star called a pulsar. The discovery bestows the stellar pair with the record for the shortest-known orbital period for a certain class of pulsar binary system.

The data from NICER also show J17062’s stars are only about 186,000 miles (300,000 kilometers) apart, less than the distance between Earth and the Moon. Based on the pair’s breakneck orbital period and separation, scientists involved in a new study of the system think the second star is a hydrogen-poor white dwarf.

“It’s not possible for a hydrogen-rich star, like our Sun, to be the pulsar’s companion,” said Tod Strohmayer an astrophysicist at Goddard and lead author on the paper. “You can’t fit a star like that into an orbit so small.”

A previous 20-minute observation by the Rossi X-ray Timing Explorer (RXTE) in 2008 was only able to set a lower limit for J17062’s orbital period. NICER, which was installed aboard the International Space Station last June, has been able to observe the system for much longer periods of time. In August, the instrument focused on J17062 for more than seven hours over 5.3 days. Combining additional observations in October and November, the science team was able to confirm the record-setting orbital period for a binary system containing what astronomers call an accreting millisecond X-ray pulsar (AMXP).

When a massive star goes supernova, its core collapses into a black hole or a neutron star, which is small and superdense — around the size of a city but containing more mass than the Sun. Neutron stars are so hot the light they radiate passes red-hot, white-hot, UV-hot and enters the X-ray portion of the electromagnetic spectrum. A pulsar is a rapidly spinning neutron star.

The 2008 RXTE observation of J17062 found X-ray pulses recurring 163 times a second. These pulses mark the locations of hot spots around the pulsar’s magnetic poles, so they allow astronomers to determine how fast it’s spinning. J17062’s pulsar is rotating at about 9,800 revolutions per minute.

Hot spots form when a neutron star’s intense gravitational field pulls material away from a stellar companion — in J17062, from the white dwarf — where it collects into an accretion disk. Matter in the disk spirals down, eventually making its way onto the surface. Neutron stars have strong magnetic fields, so the material lands on the surface of the star unevenly, traveling along the magnetic field to the magnetic poles where it creates hot spots.

The constant barrage of in-falling gas causes accreting pulsars to spin more rapidly. As they spin, the hot spots come in and out of the view of X-ray instruments like NICER, which record the fluctuations. Some pulsars rotate over 700 times per second, comparable to the blades of a kitchen blender. X-ray fluctuations from pulsars are so predictable that NICER’s companion experiment, the Station Explorer for X-ray Timing and Navigation Technology (SEXTANT), has already shown they can serve as beacons for autonomous navigation by future spacecraft.

Over time, material from the donor star builds up on the surface of the neutron star. Once the pressure of this layer builds up to the point where its atoms fuse, a runaway thermonuclear reaction occurs, releasing the energy equivalent of 100 15-megaton bombs exploding over every square centimeter, explained Strohmayer. X-rays from such outbursts can also be captured by NICER, although one has yet to be seen from J17062.

The researchers were able to determine that J17062’s stars revolve around each other in a circular orbit, which is common for AMXPs. The white dwarf donor star is a “lightweight,” only around 1.5 percent of our Sun’s mass. The pulsar is much heavier, around 1.4 solar masses, which means the stars orbit a point around 1,900 miles (3,000 km) from the pulsar. Strohmayer said it’s almost as if the donor star orbits a stationary pulsar, but NICER is sensitive enough to detect a slight fluctuation in the pulsar’s X-ray emission due to the tug from the donor star.

“The distance between us and the pulsar is not constant,” Strohmayer said. “It’s varying by this orbital motion. When the pulsar is closer, the X-ray emission takes a little less time to reach us than when it’s further away. This time delay is small, only about 8 milliseconds for J17062’s orbit, but it’s well within the capabilities of a sensitive pulsar machine like NICER.”

The results of the study were published May 9 in The Astrophysical Journal Letters.

NICER’s mission is to provide high-precision measurements to further study the physics and behavior of neutron stars. Other first-round results from the instrument have provided details about one object’s thermonuclear bursts and explored what happens to the accretion disk during these events.

“Neutron stars turn out to be truly unique nuclear physics laboratories, from a terrestrial standpoint,” said Zaven Arzoumanian, a Goddard astrophysicist and lead scientist for NICER. “We can’t recreate the conditions on neutron stars anywhere within our solar system. One of NICER’s key objectives is to study subatomic physics that isn’t accessible anywhere else.”

NICER is an Astrophysics Mission of Opportunity within NASA’s Explorer program, which provides frequent flight opportunities for world-class scientific investigations from space utilizing innovative, streamlined, and efficient management approaches within the heliophysics and astrophysics science areas. NASA’s Space Technology Mission Directorate supports the SEXTANT component of the mission, demonstrating pulsar-based spacecraft navigation.

By Jeanette Kazmierczak

NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, Md.