A new experiment facility, now undergoing testing at NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama, will be flown to the International Space Station in 2018. The primary focus of experiments in the new Life Sciences Glovebox will be to aid research on the long-term impact of microgravity on human physiology — potentially leading to innovative techniques for protecting human explorers during bold new missions into deep space, and also improving life on Earth.

The fully enclosed, acrylic-windowed facility is roughly the size of a large fish tank. It has 15 cubic feet of workspace and features two glove ports on the front window, and two each on the right and left sides. The access points permit up to two astronaut crew members, sometimes guided in real-time by scientists back on Earth, to conduct one or more experiments simultaneously. The limited access points enable researchers to minimize contact with materials potentially hazardous to their health or difficult for the space station’s air scrubbers to filter out.

Scheduled for launch to the space station in August 2018, the new glovebox is cousin to the veteran Microgravity Science Glovebox. That workhorse facility, installed on the space station in 2002 and currently housed in the station’s “Destiny” laboratory, has seen high demand for access from scientists around the world, all of them vying for lab time involving the one-of-a-kind orbiting research apparatus. The heavy volume of requests led to development and construction of the new Life Sciences Glovebox, said Susan Spencer, deputy project manager for the new facility being developed at Marshall.

“For 15 years, the Microgravity Glovebox has been constantly in use and constantly in demand,” Spencer said. “That comes as no surprise, given its one-of-a-kind nature. But it was clear we needed to relieve the payload congestion — providing a second facility to better serve the research community competing for glovebox experiment time.”

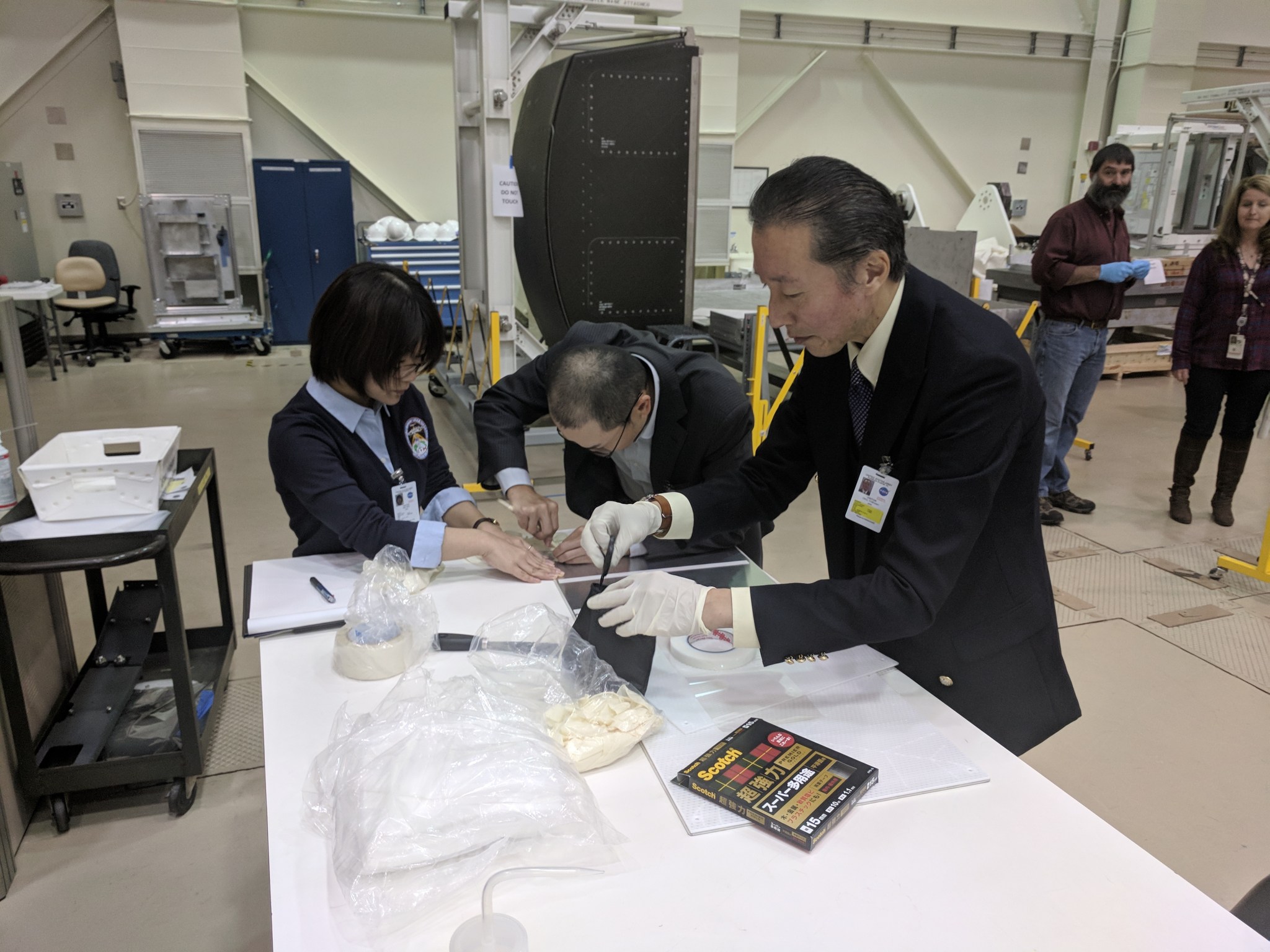

The Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency built the new facility in partnership with the Dutch commercial firm Bradford Engineering several years ago. The partners recently revived the Life Sciences Glovebox effort, updating heritage hardware and preparing it for flight, to answer the increased demand for research time in the glovebox. Marshall contributed the secondary structure to support the glovebox and its thermal control and power control systems.

“It’s been an amazing team effort across Marshall, NASA and the international partnership to ready this hardware for launch, from the refinement of heritage JAXA hardware to the avionics design, plus integration and testing support from across Marshall’s Engineering Directorate,” Spencer said.

The new facility will be installed in the space station’s Japanese “Kibo” module, housed in an existing, zero-gravity stowage rack. Featuring a power supply designed by Marshall, as well as air filtration, adjustable lighting, video and data recording and real-time downlink capability, the glovebox will enable biologists and other researchers to continuously observe and participate in their experiments — experiencing nearly the same degree of oversight they enjoy in their own labs on Earth.

Marshall will finish its integration and testing of glovebox elements in coming months and ship the facility to Japan in March 2018, where it will undergo preparation for its launch to the station. The avionics package is set to be launched to the station next June, with ancillary hardware and critical spare parts manifested on various commercial spaceflights. The roughly 900-pound core facility itself will be last to be launched.

“The glovebox core facility, set to fly to space in a refrigerator-freezer rack modified by Boeing to accommodate the core facility packed in the foam clamshell, will be the largest soft-stowed payload ever flown,” Spencer said proudly. “Soft-stowing,” or packing flight hardware in foam and then securely containing it for launch, is an efficient, low-cost alternative to the conventional approach of hard-mounting flight hardware inside the launch vehicle.

The first new experiment in the glovebox should be underway by November 2018. But Spencer said she’s already as proud of this endeavor as any flight project she’s supported in her nearly 30 years with NASA.

“My goal in life was always to build and fly hardware to space,” she said. “Seeing something you’ve had your hands on lift off and fly? Watching the launch of a flight mission you’ve contributed your best work to? There’s nothing like that experience.”

Marshall manages both gloveboxes for NASA and its international partners. As with all station science, the ISS Research Integration Office at NASA’s Johnson Space Center in Houston coordinates with researchers, while Marshall monitors round-the-clock science operations and communications from the Payload Operations Integration Center.

To learn more about Marshall’s work supporting NASA’s mission in space, visit: