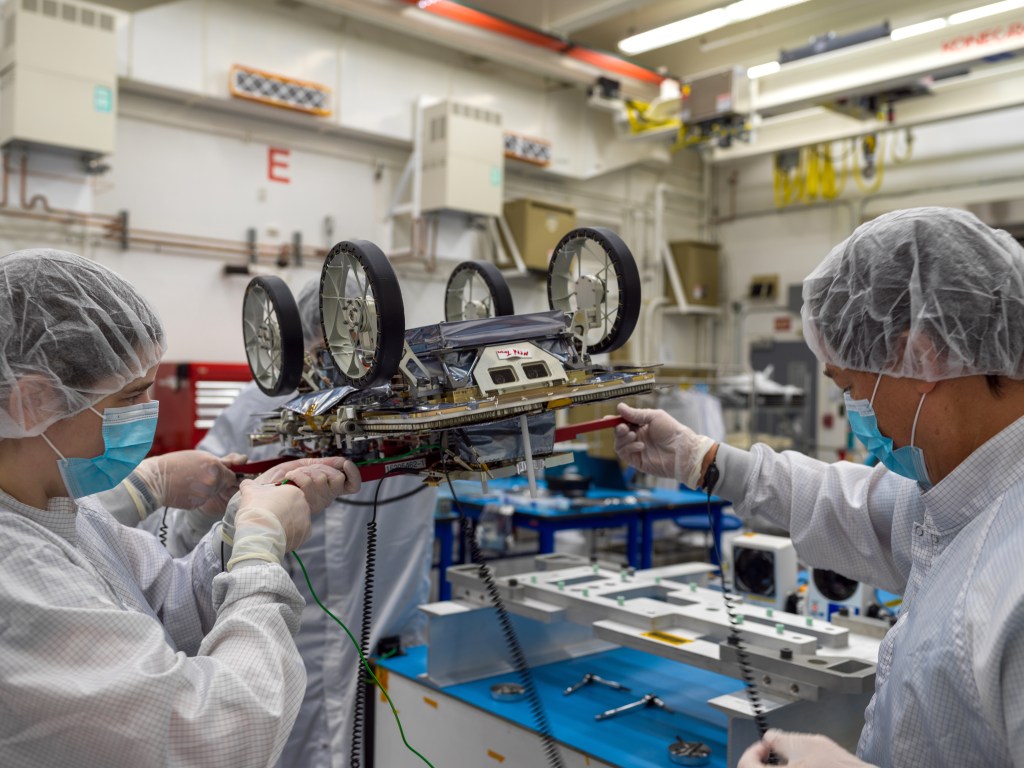

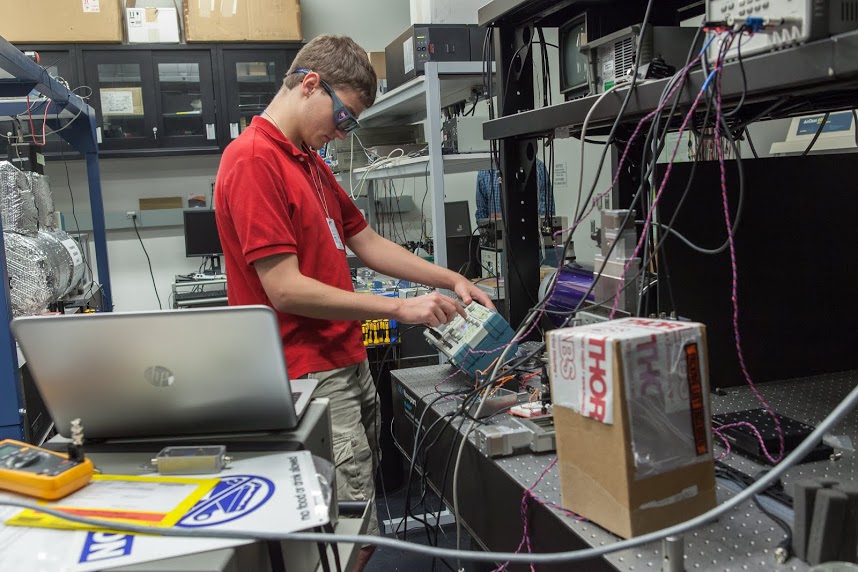

Puffs of smoke waft from a circuit board as interns solder tiny circuits for the Evolved Laser Interferometer Space Antenna.

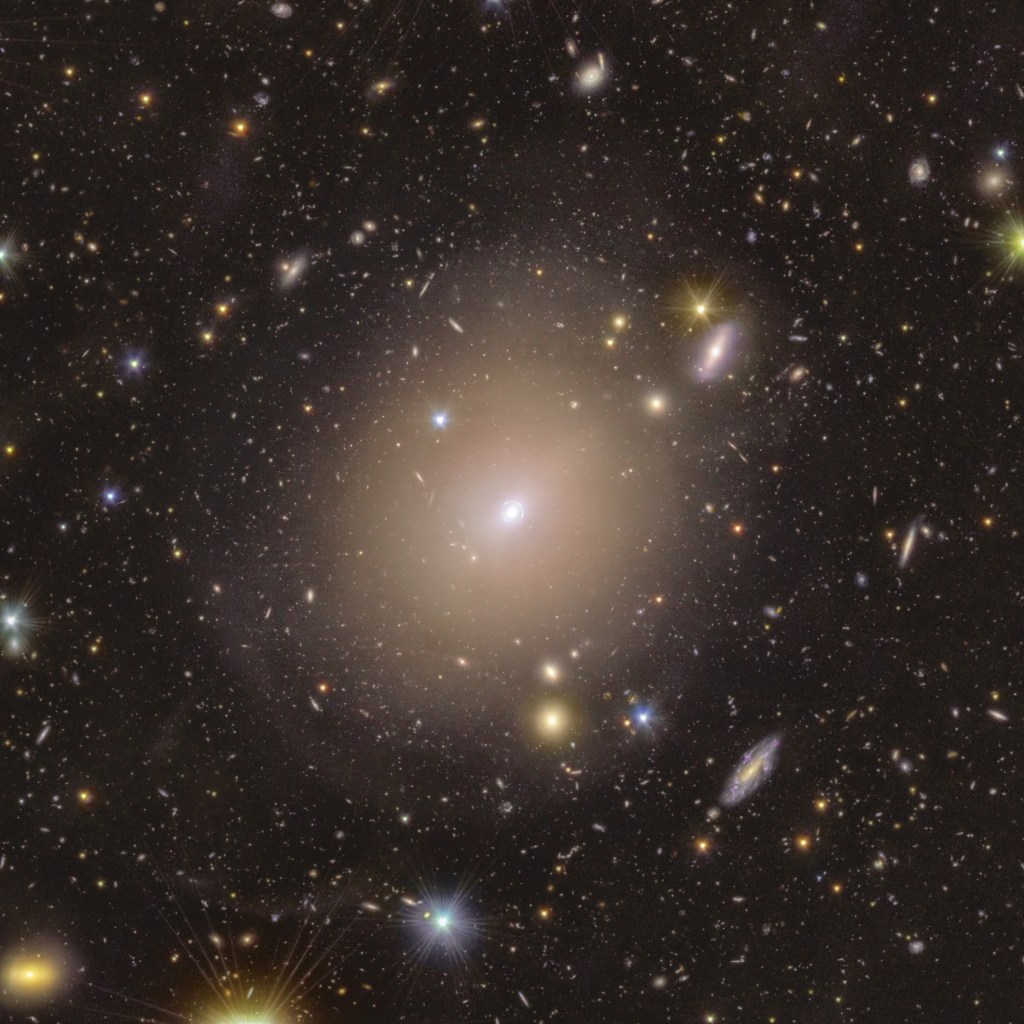

“We’re looking for evidence of black holes,” Robert Buttles said. “As of now we only have images of material spinning around a black hole, but we haven’t been able to physically measure the black hole itself.”

Pairs of black holes radiate gravitational waves as they orbit each other in a binary system. Analyzing these waves can allow scientists to study black holes directly.

“All other emission from a black hole binary is actually from material around the black hole—for example, gas falling into the black hole from an accretion disk and generating x-rays—but not [data] from the black hole itself,” said Jeffery Livas, an astrophysicist working on the eLISA.

Ripples occur when a stone falls into the water. The same applies with gravity when a black hole binary disturbs nearby regions of spacetime. These gravitational ripples cause the cosmos to oscillate imperceptibly, stretching even our bodies here on Earth by trillionths of meters.

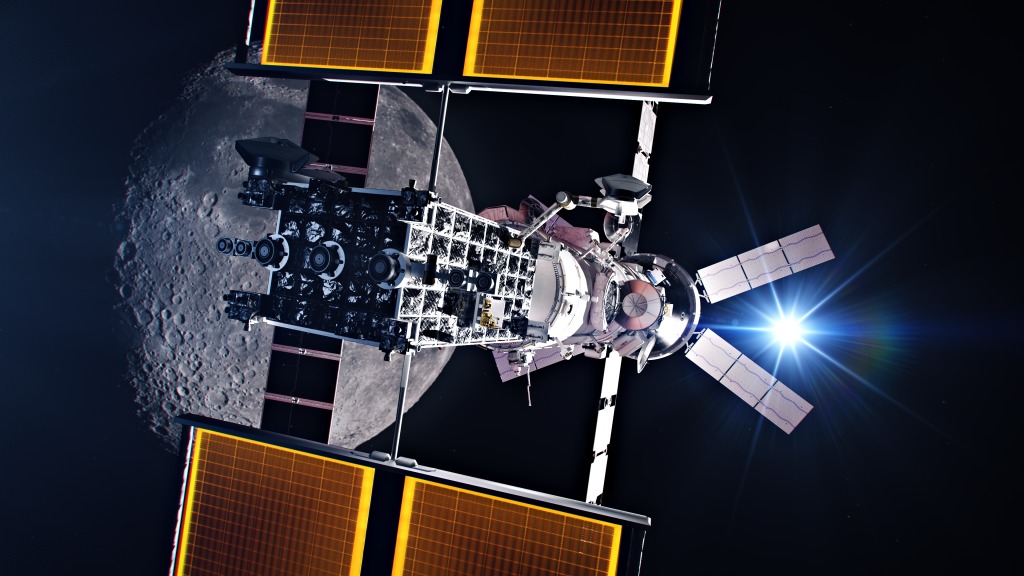

The eLISA mission aims to identify, locate, and study the sources of these waves to learn about the formation of large-scale structure in the universe and test general relativity with precise observations. This observatory consists of three satellites, each housing two metallic test masses that magnetism, radiation, and interplanetary fields cannot rattle.

“You want the masses to be shielded from everything except for gravity,” Livas said. “We don’t know how to shield from gravity. And these masses floating in space have no net force on them. We then range the distance between them with a laser beam. And if we see a pattern where the distance changes, where the shape stretches in one direction and scrunches in another, we mark that oscillation as a gravitational wave.”

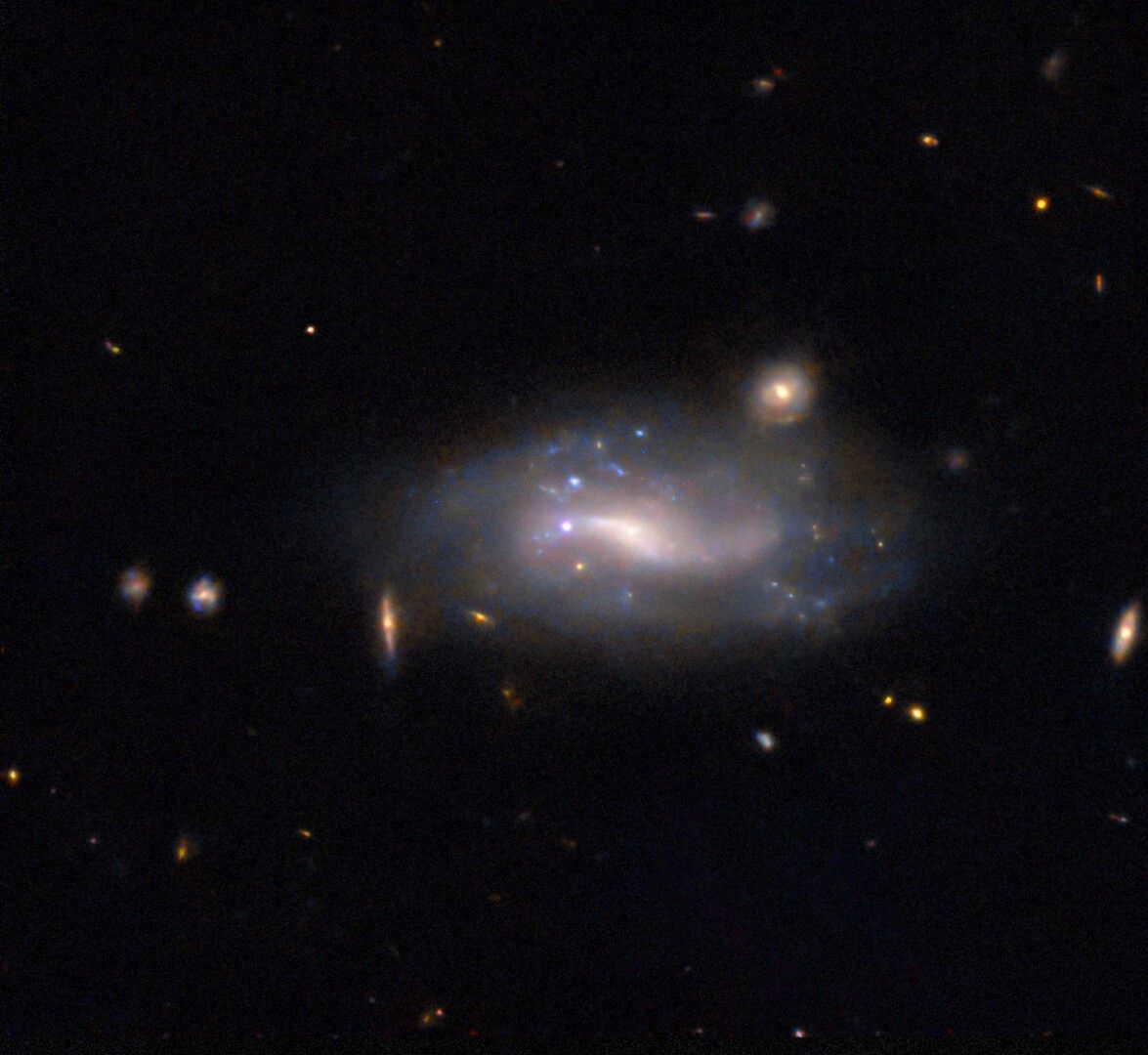

Gravitational waves require incredibly dense masses moving at extremely high speeds to form. Binary star systems, galaxies colliding, and other forces scientists have yet to discover could also generate gravitational waves.

“We expect there will be sources we don’t know anything about or have not yet imagined,” Livas said.