The last astronauts of the Apollo program were lucky. Not just because they were chosen to fly to the Moon, but because they missed some really bad weather en route. This wasn’t a hurricane or heat wave, but space weather – the term for radiation in the solar system, much of which is released by the Sun. In August 1972, right in between the Apollo 16 and Apollo 17 missions, a solar storm occurred sending out dangerous bursts of radiation. On Earth, we’re protected by our magnetic field, but out in space, this would have been hazardous for the astronauts.

The ability to forecast these kinds of events is increasingly important as NASA prepares to send the first woman and the next man to the Moon under the Artemis program. Research now underway may have found a reliable new method to predict this solar activity. The Sun’s activity rises and falls in an 11-year cycle. The forecast for the next solar cycle says it will be the weakest of the last 200 years. The maximum of this next cycle – measured in terms of sunspot number, a standard measure of solar activity level – could be 30 to 50% lower than the most recent one. The results show that the next cycle will start in 2020 and reach its maximum in 2025.

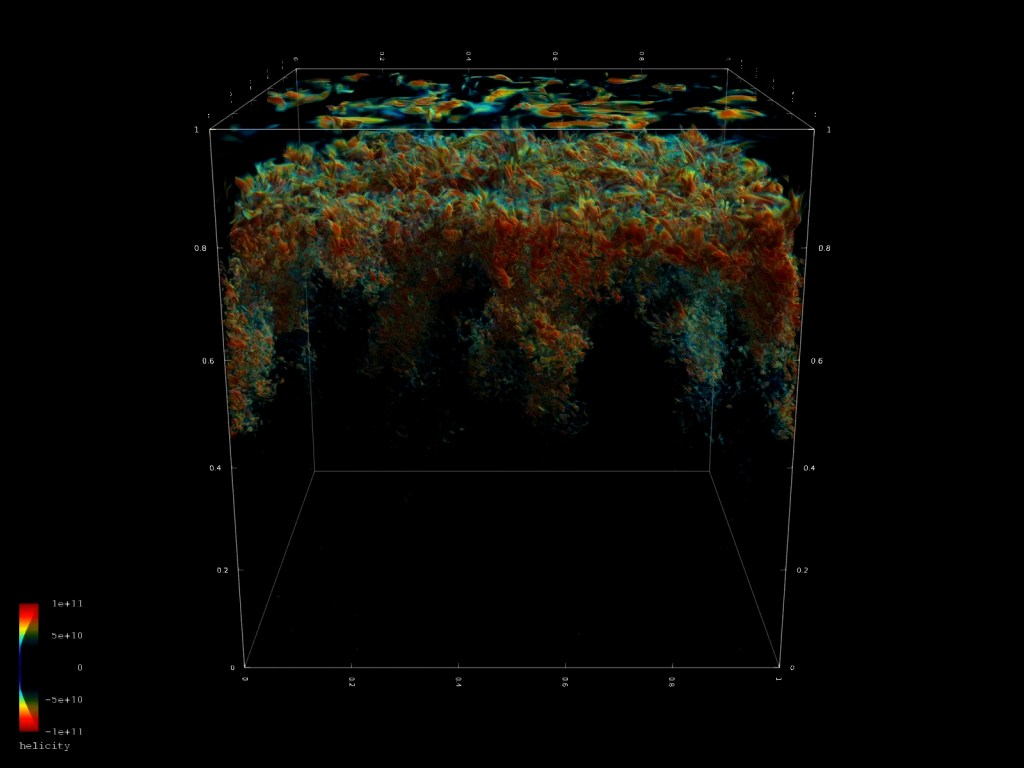

Sunspots are regions on the Sun with magnetic fields thousands of times stronger than the Earth’s. Fewer of them at the point of maximum solar activity means fewer dangerous blasts of radiation.

Both the forecast and the improving ability to make such predictions about space weather are good news for mission planners who can schedule human exploration missions during periods of lower radiation, when possible.

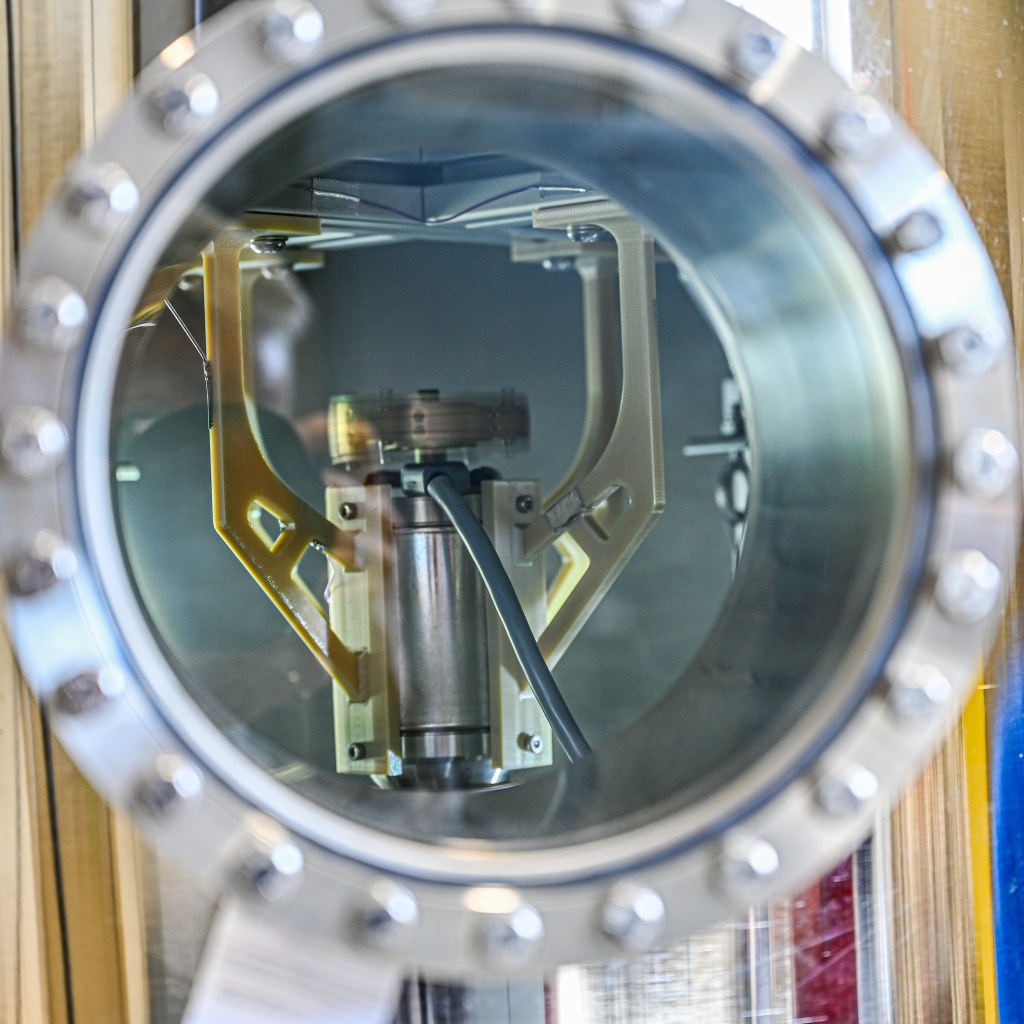

The new research was led by Irina Kitiashvili, a researcher with the Bay Area Environmental Research Institute at NASA’s Ames Research Center, in California’s Silicon Valley. It combined observations from two NASA space missions – the Solar and Heliospheric Observatory and the Solar Dynamics Observatory – with data collected since 1976 from the ground-based National Solar Observatory.

One challenge for researchers working to predict the Sun’s activities is that scientists don’t yet completely understand the inner workings of our star. Plus, some factors that play out deep inside the Sun cannot be measured directly. They have to be estimated from measurements of related phenomena on the solar surface, like sunspots.

Kitiashvili’s method differs from other prediction tools in terms of the raw material for its forecast. Previously, researchers used the number of sunspots to represent indirectly the activity of the solar magnetic field. The new approach takes advantage of direct observations of magnetic fields emerging on the surface of the Sun – data which has only existed for the last four solar cycles.

Mathematically combining the data from the three sources of Sun observations with the estimates of its interior activity generated a forecast designed to be more reliable than using any of those sources alone.

In 2008 the researchers used this method to make their prediction, which was then put to the test as the current solar cycle unfolded over the last decade. It has performed well, with the forecast strength and timing of the solar maximum aligning closely with reality.

Knowing how the Sun will behave can offer necessary insight to plan protections for our next explorers who will venture into deep space. It also lets us protect technology we depend on: satellite missions studying the universe from space, landers and rovers heading to the Moon and Mars, and the telecommunications satellites right in our own backyard.

NASA is charged to get American astronauts to the Moon in the next five years with a landing on the lunar South Pole. With a calm and quiet space weather forecast for the coming decade, it is a great time to explore!

—

Kitiashvili’s work was supported by the National Science Foundation and by NASA.

Learn more about how NASA will protect astronauts on deep-space missions aboard the Orion crew capsule: Scientists and Engineers Evaluate Orion Radiation Protection Plan.

For news media:

For more information about this subject, please contact the NASA Ames newsroom.