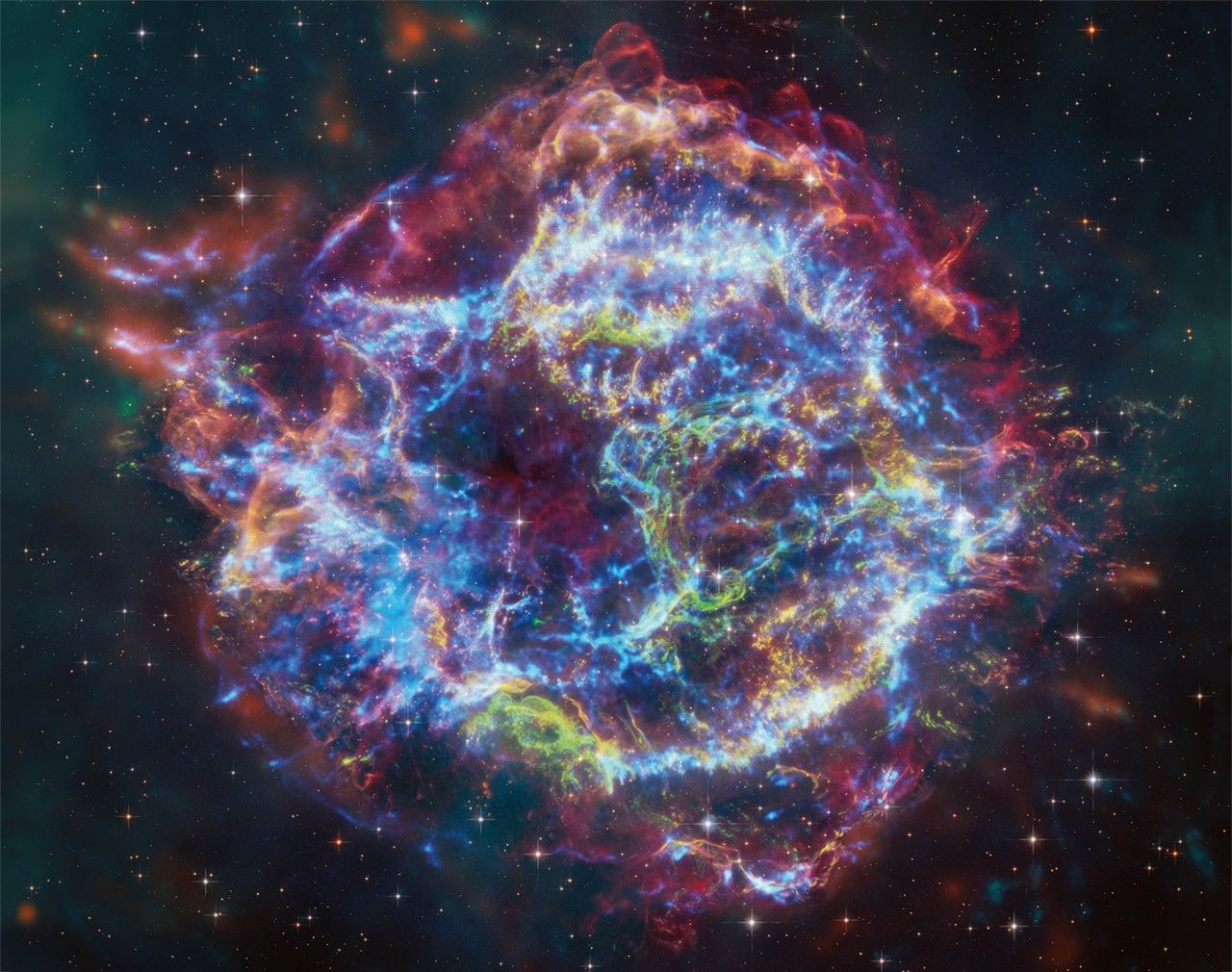

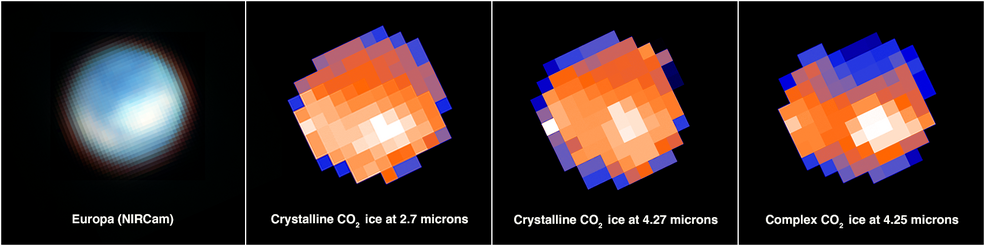

Astronomers using data from NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope have identified carbon dioxide in a specific region on the icy surface of Jupiters moon Europa.

Jupiter’s moon Europa is one of a handful of worlds in our solar system that could potentially harbor conditions suitable for life. Previous research has shown that beneath its water-ice crust lies a salty ocean of liquid water with a rocky seafloor. However, planetary scientists had not confirmed if that ocean contained the chemicals needed for life, particularly carbon.

Astronomers using data from NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope have identified carbon dioxide in a specific region on the icy surface of Europa. Analysis indicates that this carbon likely originated in the subsurface ocean and was not delivered by meteorites or other external sources. Moreover, it was deposited on a geologically recent timescale. This discovery has important implications for the potential habitability of Europa’s ocean.

“On Earth, life likes chemical diversity – the more diversity, the better. We’re carbon-based life. Understanding the chemistry of Europa’s ocean will help us determine whether it’s hostile to life as we know it, or if it might be a good place for life,” said Geronimo Villanueva of NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, lead author of one of two independent papers describing the findings.

“We now think that we have observational evidence that the carbon we see on Europa’s surface came from the ocean. That’s not a trivial thing. Carbon is a biologically essential element,” added Samantha Trumbo of Cornell University in Ithaca, New York, lead author of the second paper analyzing these data.

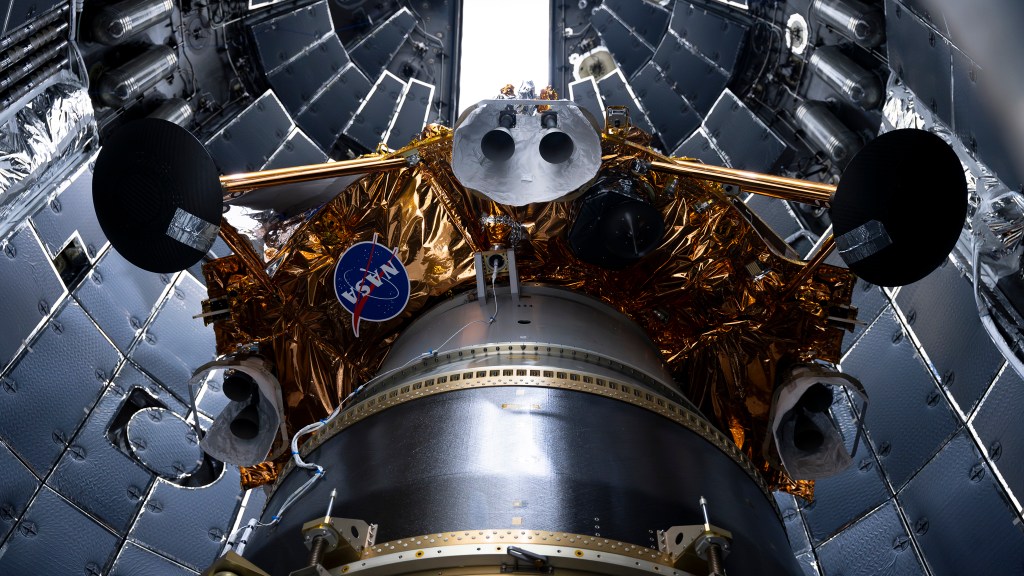

NASA plans to launch its Europa Clipper spacecraft, which will perform dozens of close flybys of Europa to further investigate whether it could have conditions suitable for life, in October 2024.

A Surface-Ocean Connection

Webb finds that on Europa’s surface, carbon dioxide is most abundant in a region called Tara Regio – a geologically young area of generally resurfaced terrain known as “chaos terrain.” The surface ice has been disrupted, and there likely has been an exchange of material between the subsurface ocean and the icy surface.

“Previous observations from the Hubble Space Telescope show evidence for ocean-derived salt in Tara Regio,” explained Trumbo. “Now we’re seeing that carbon dioxide is heavily concentrated there as well. We think this implies that the carbon probably has its ultimate origin in the internal ocean.”

“Scientists are debating how much Europa’s ocean connects to its surface. I think that question has been a big driver of Europa exploration,” said Villanueva. “This suggests that we may be able to learn some basic things about the ocean’s composition even before we drill through the ice to get the full picture.”

Both teams identified the carbon dioxide using data from the integral field unit of Webb’s Near-Infrared Spectrograph (NIRSpec). This instrument mode provides spectra with a resolution of 200 x 200 miles (320 x 320 kilometers) on the surface of Europa, which has a diameter of 1,944 miles, allowing astronomers to determine where specific chemicals are located.

Carbon dioxide isn’t stable on Europa’s surface. Therefore, the scientists say it’s likely that it was supplied on a geologically recent timescale – a conclusion bolstered by its concentration in a region of young terrain.

“These observations only took a few minutes of the observatory’s time,” said Heidi Hammel of the Association of Universities for Research in Astronomy, a Webb interdisciplinary scientist leading Webb’s Cycle 1 Guaranteed Time Observations of the solar system. “Even with this short period of time, we were able to do really big science. This work gives a first hint of all the amazing solar system science we’ll be able to do with Webb.”

Searching for a Plume

Villanueva’s team also looked for evidence of a plume of water vapor erupting from Europa’s surface. Researchers using NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope reported tentative detections of plumes in 2013, 2016, and 2017. However, finding definitive proof has been difficult.

The new Webb data shows no evidence of plume activity, which allowed Villanueva’s team to set a strict upper limit on the rate of material potentially being ejected. The team stressed, however, that their non-detection does not rule out a plume.

“There is always a possibility that these plumes are variable and that you can only see them at certain times. All we can say with 100% confidence is that we did not detect a plume at Europa when we made these observations with Webb,” said Hammel.

These findings may help inform NASA’s Europa Clipper mission, as well as ESA’s (European Space Agency’s) upcoming Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer (JUICE).

The two papers will be published in Science on Sept. 21.

The James Webb Space Telescope is the world’s premier space science observatory. Webb is solving mysteries in our solar system, looking beyond to distant worlds around other stars, and probing the mysterious structures and origins of our universe and our place in it. Webb is an international program led by NASA with its partners, ESA (European Space Agency) and the Canadian Space Agency.

Media Contacts:

Laura Betz

NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, Md.

laura.e.betz@nasa.gov

Christine Pulliam

Space Telescope Science Institute, Baltimore, Md.

cpulliam@stsci.edu