Last night, NASA’s Juno mission to Jupiter successfully executed a 10.5-hour propulsive maneuver — extraordinarily long by mission standards. The goal of the burn, as it’s known, will keep the solar-powered spacecraft out of what would have been a mission-ending shadow cast by Jupiter on the spacecraft during its next close flyby of the planet on Nov. 3, 2019.

Juno began the maneuver yesterday, on Sept. 30, at 7:46 p.m. EDT (4:46 p.m. PDT) and completed it early on Oct. 1. Using the spacecraft’s reaction-control thrusters, the propulsive maneuver lasted five times longer than any previous use of that system. It changed Juno’s orbital velocity by 126 mph (203 kph) and consumed about 160 pounds (73 kilograms) of fuel. Without this maneuver, Juno would have spent 12 hours in transit across Jupiter’s shadow — more than enough time to drain the spacecraft’s batteries. Without power, and with spacecraft temperatures plummeting, Juno would likely succumb to the cold and be unable to awaken upon exit.

“With the success of this burn, we are on track to jump the shadow on Nov. 3,” said Scott Bolton, Juno principal investigator at the Southwest Research Institute in San Antonio. “Jumping over the shadow was an amazingly creative solution to what seemed like a fatal geometry. Eclipses are generally not friends of solar-powered spacecraft. Now instead of worrying about freezing to death, I am looking forward to the next science discovery that Jupiter has in store for Juno.”

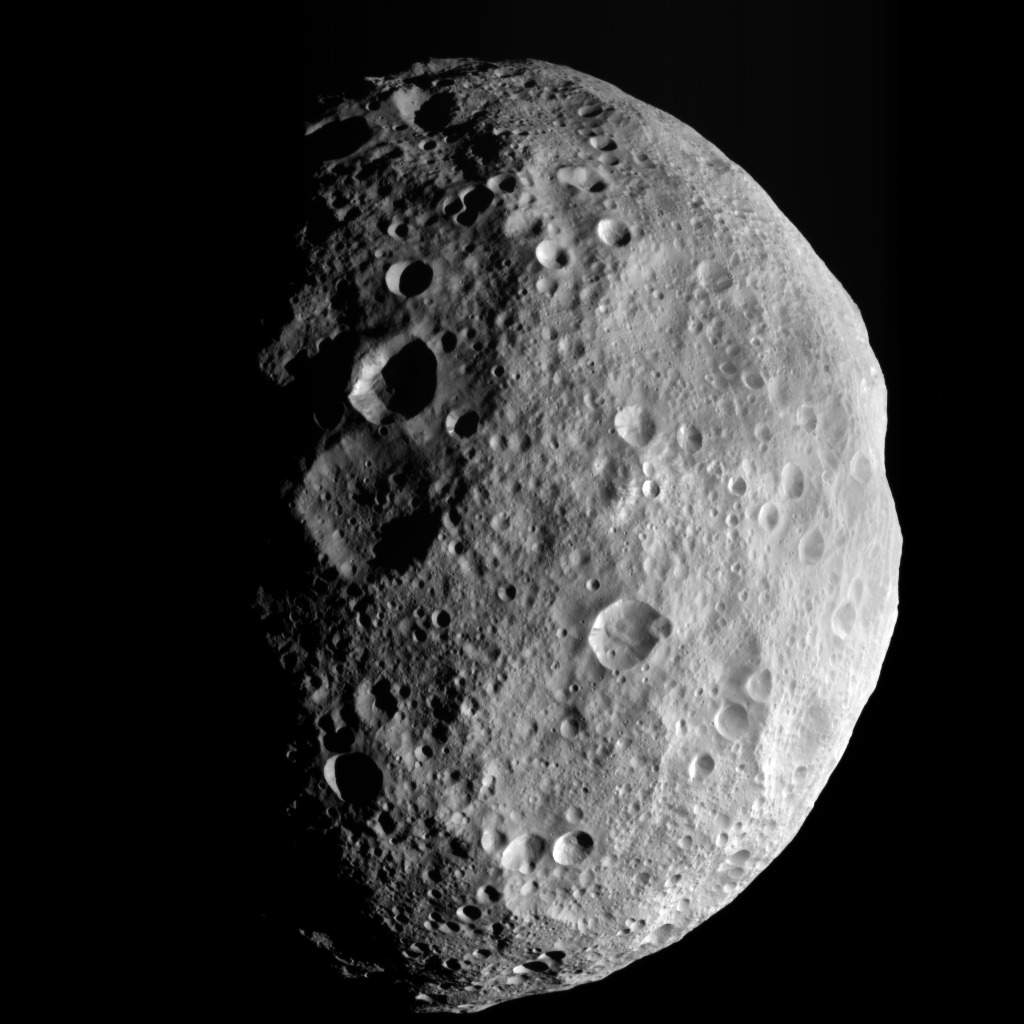

Juno has been navigating in deep space since 2011. It entered an initial 53-day orbit around Jupiter on July 4, 2016. Originally, the mission planned to reduce the size of its orbit a few months later to decrease the period between science flybys of the gas giant to every 14 days. But the project team recommended to NASA to forgo the main engine burn due to concerns about the spacecraft’s fuel delivery system. Juno’s 53-day orbit provides all the science as originally planned; it just takes longer to do so. The spacecraft’s longer life at Jupiter is what led to the need to avoid the gas giant’s shadow.

“Pre-launch mission planning did not anticipate a lengthy eclipse that would plunge our solar-powered spacecraft into darkness,” said Ed Hirst, Juno project manager at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California. “That we could plan and execute the necessary maneuver while operating in Jupiter’s orbit is a testament to the ingenuity and skill of our team, along with the extraordinary capability and versatility of our spacecraft.”

NASA’s JPL manages the Juno mission for the principal investigator, Scott Bolton, of the Southwest Research Institute in San Antonio. Juno is part of NASA’s New Frontiers Program, which is managed by NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama, for the agency’s Science Mission Directorate. The Italian Space Agency (ASI) contributed two instruments, a Ka-band frequency translator (KaT) and the Jovian Infrared Auroral Mapper (JIRAM). Lockheed Martin Space in Denver built and operates the spacecraft.

More information about Juno is available at:

https://www.missionjuno.swri.edu

More information on Jupiter is at:

The public can follow the mission on Facebook and Twitter at:

https://www.facebook.com/NASAJuno

https://www.twitter.com/NASAJuno

DC Agle

Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena, Calif.

818-393-9011

agle@jpl.nasa.gov

Alana Johnson

NASA Headquarters, Washington

202-672-4780

alana.r.johnson@nasa.gov

Deb Schmid

Southwest Research Institute, San Antonio

210-522-2254

dschmid@swri.org

2019-196