Dusty solar panels and darker skies are expected to bring the Mars lander mission to a close around the end of this year.

NASA’s InSight Mars lander is gradually losing power and is anticipated to end science operations later this summer. By December, InSight’s team expects the lander to have become inoperative, concluding a mission that has thus far detected more than 1,300 marsquakes – most recently, a magnitude 5 that occurred on May 4 – and located quake-prone regions of the Red Planet.

The information gathered from those quakes has allowed scientists to measure the depth and composition of Mars’ crust, mantle, and core. Additionally, InSight (short for Interior Exploration using Seismic Investigations, Geodesy and Heat Transport) has recorded invaluable weather data and studied remnants of Mars’ ancient magnetic field.

“InSight has transformed our understanding of the interiors of rocky planets and set the stage for future missions,” said Lori Glaze, director of NASA’s Planetary Science Division. “We can apply what we’ve learned about Mars’ inner structure to Earth, the Moon, Venus, and even rocky planets in other solar systems.”

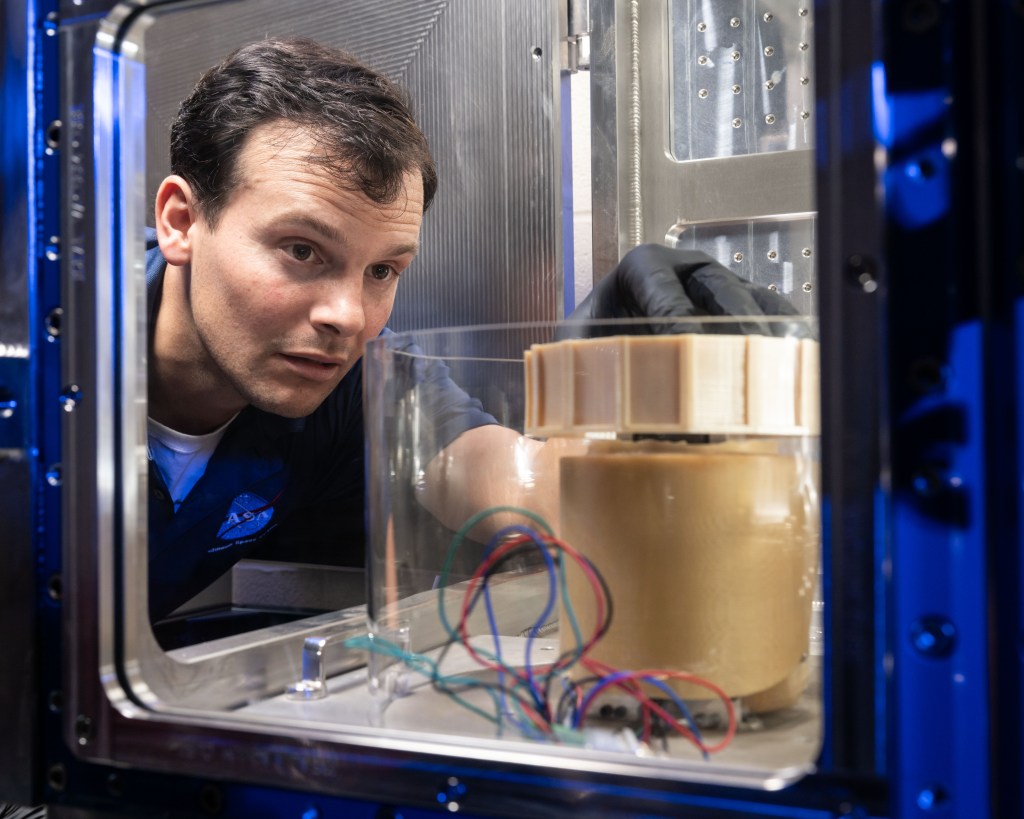

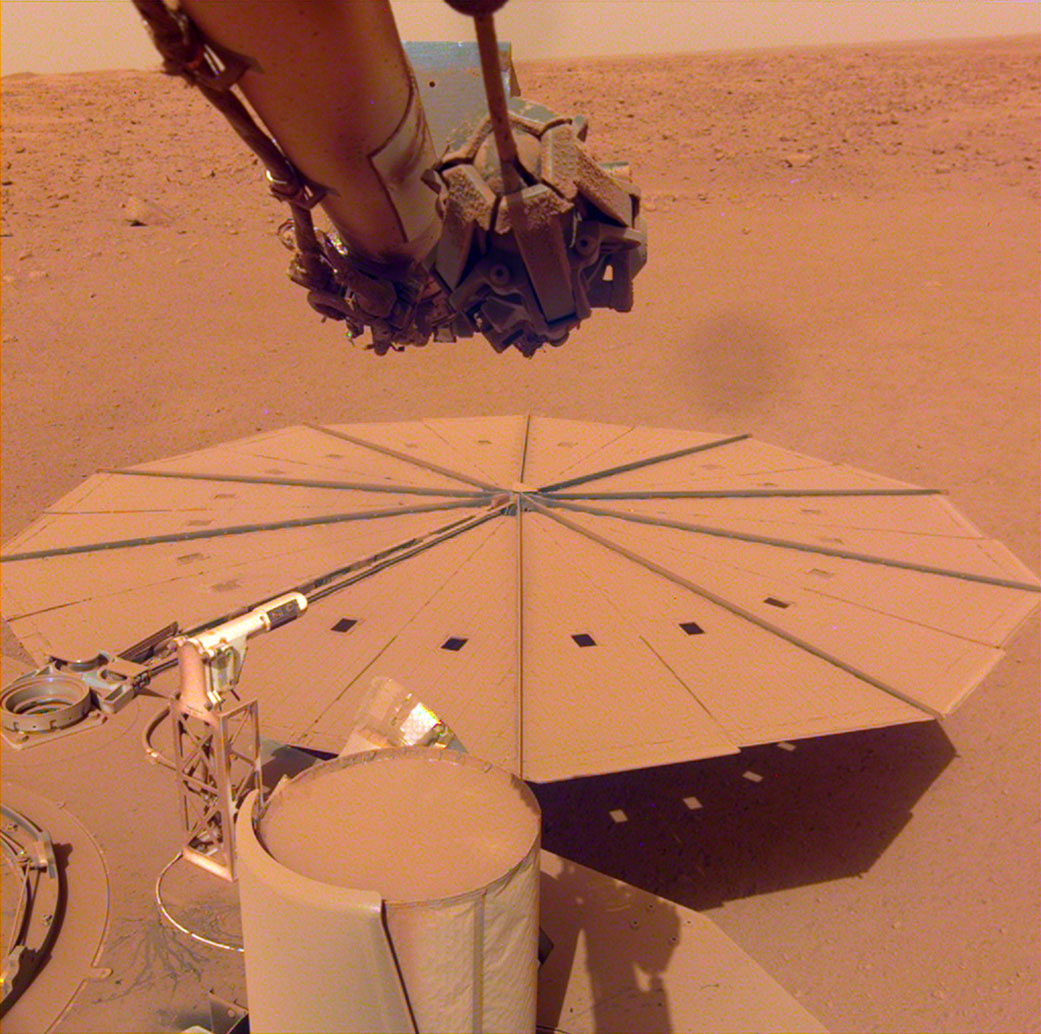

InSight landed on Mars Nov. 26, 2018. Equipped with a pair of solar panels that each measures about 7 feet (2.2 meters) wide, it was designed to accomplish the mission’s primary science goals in its first Mars year (nearly two Earth years). Having achieved them, the spacecraft is now into an extended mission, and its solar panels have been producing less power as they continue to accumulate dust.

Because of the reduced power, the team will soon put the lander’s robotic arm in its resting position (called the “retirement pose”) for the last time later this month. Originally intended to deploy the seismometer and the lander’s heat probe, the arm has played an unexpected role in the mission: Along with using it to help bury the heat probe after sticky Martian soil presented the probe with challenges, the team used the arm in an innovative way to remove dust from the solar panels. As a result, the seismometer was able to operate more often than it would have otherwise, leading to new discoveries.

When InSight landed, the solar panels produced around 5,000 watt-hours each Martian day, or sol – enough to power an electric oven for an hour and 40 minutes. Now, they’re producing roughly 500 watt-hours per sol – enough to power the same electric oven for just 10 minutes.

Additionally, seasonal changes are beginning in Elysium Planitia, InSight’s location on Mars. Over the next few months, there will be more dust in the air, reducing sunlight – and the lander’s energy. While past efforts removed some dust, the mission would need a more powerful dust-cleaning event, such as a “dust devil” (a passing whirlwind), to reverse the current trend.

“We’ve been hoping for a dust cleaning like we saw happen several times to the Spirit and Opportunity rovers,” said Bruce Banerdt, InSight’s principal investigator at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Southern California, which leads the mission. “That’s still possible, but energy is low enough that our focus is making the most of the science we can still collect.”

If just 25% of InSight’s panels were swept clean by the wind, the lander would gain about 1,000 watt-hours per sol – enough to continue collecting science. However, at the current rate power is declining, InSight’s non-seismic instruments will rarely be turned on after the end of May.

Energy is being prioritized for the lander’s seismometer, which will operate at select times of day, such as at night, when winds are low and marsquakes are easier for the seismometer to “hear.” The seismometer itself is expected to be off by the end of summer, concluding the science phase of the mission.

At that point, the lander will still have enough power to operate, taking the occasional picture and communicating with Earth. But the team expects that around December, power will be low enough that one day InSight will simply stop responding.

More About the Mission

JPL manages InSight for NASA’s Science Mission Directorate. InSight is part of NASA’s Discovery Program, managed by the agency’s Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama. Lockheed Martin Space in Denver built the InSight spacecraft, including its cruise stage and lander, and supports spacecraft operations for the mission.

A number of European partners, including France’s Centre National d’Études Spatiales (CNES) and the German Aerospace Center (DLR), are supporting the InSight mission. CNES provided the Seismic Experiment for Interior Structure (SEIS) instrument to NASA, with the principal investigator at IPGP (Institut de Physique du Globe de Paris). Significant contributions for SEIS came from IPGP; the Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research (MPS) in Germany; the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology (ETH Zurich) in Switzerland; Imperial College London and Oxford University in the United Kingdom; and JPL. DLR provided the Heat Flow and Physical Properties Package (HP3) instrument, with significant contributions from the Space Research Center (CBK) of the Polish Academy of Sciences and Astronika in Poland. Spain’s Centro de Astrobiología (CAB) supplied the temperature and wind sensors.

Andrew Good

Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena, Calif.

818-393-2433

andrew.c.good@jpl.nasa.gov

Karen Fox / Alana Johnson

NASA Headquarters, Washington

301-286-6284 / 202-358-1501

karen.c.fox@nasa.gov / alana.r.johnson@nasa.gov

2022-071