Observations from research aircraft show that the Southern Ocean absorbs much more carbon from the atmosphere than it releases, confirming it is a very strong carbon sink and an important buffer for the effects of human-caused greenhouse gas emissions, according to a new, NASA-supported study.

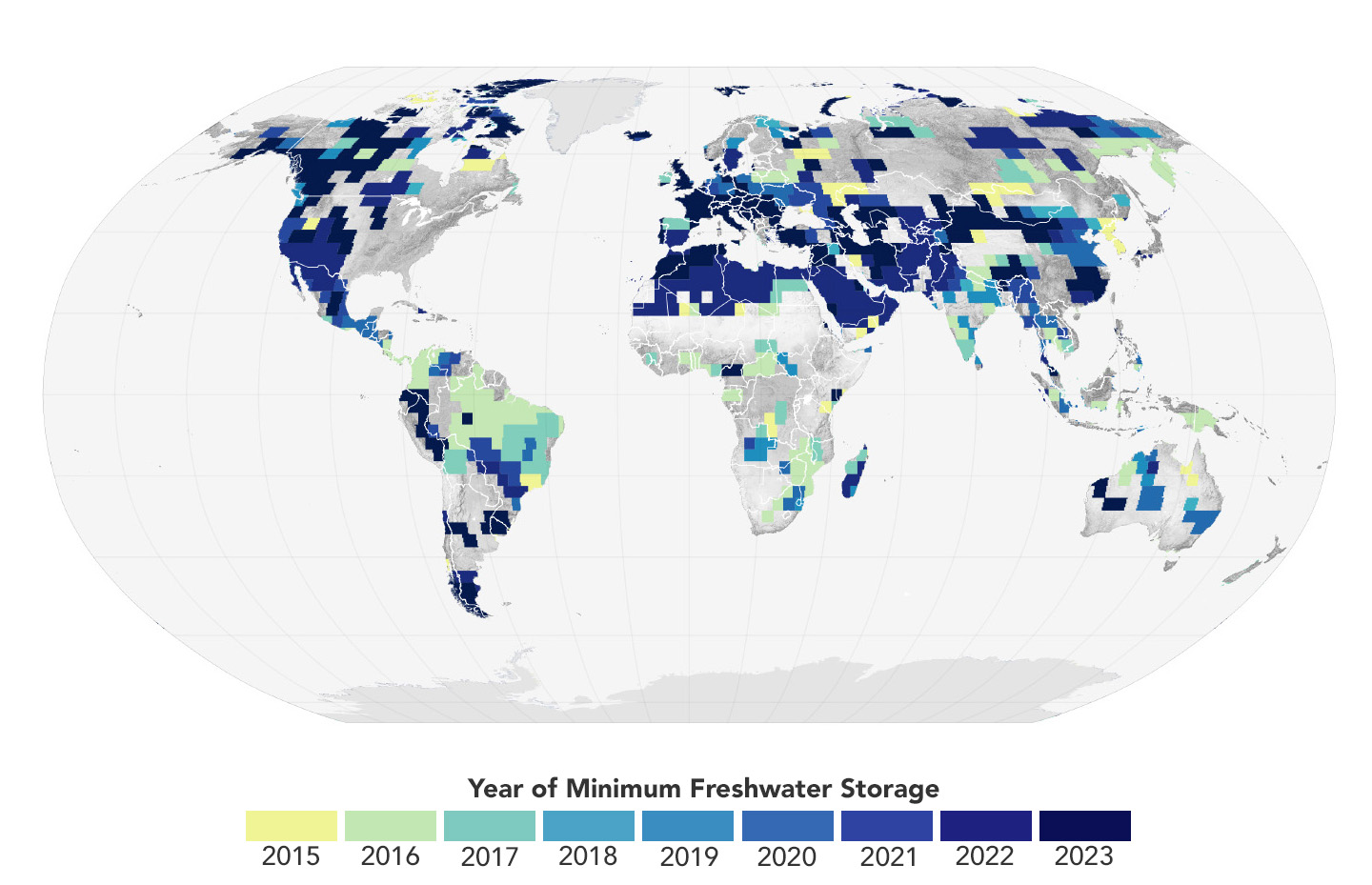

Recent research had raised uncertainty about just how much atmospheric carbon dioxide (CO2) these icy waters absorb. Those studies relied on measurements of ocean acidity – which increases when ocean water absorbs CO2 – taken by instruments that float in the ocean.

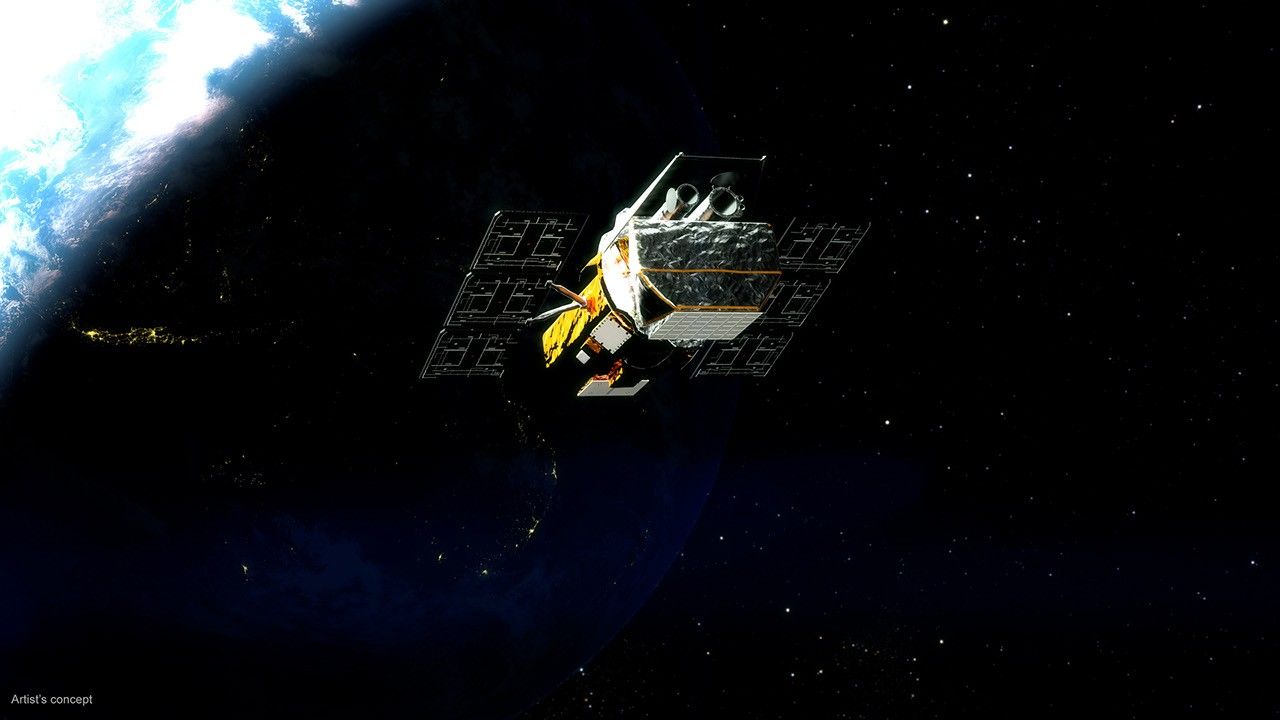

The new study, published in Science, used aircraft observations of CO2 to show that the Southern Ocean is a stronger carbon sink than previously thought, playing a significant role in mitigating the impact of greenhouse gases. Aircraft observations were collected over nearly a decade from 2009 to 2018 during three field experiments, including from NASA’s Atmospheric Tomography Mission (ATom) in 2016.

“Airborne measurements show a drawdown of carbon dioxide in the lower atmosphere over the Southern Ocean surface in summer, indicating carbon uptake by the ocean,” explained Matthew Long, lead author and a scientist at the National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR) in Boulder, Colorado.

They found that the Southern Ocean absorbs significantly more CO2 in the Southern Hemisphere summer than it releases in the winter, making it a strong carbon sink. Data from the airborne campaigns also showed a larger amount of carbon absorbed by the Southern Ocean and smaller amount released than previous estimates using ocean acidity data. The findings highlight the importance of aircraft-based observations to understand carbon cycling.

The research was funded by the National Science Foundation, NASA and NOAA.

Download this image from NASA Goddard’s Scientific Visualization Studio

The Ocean as a Sponge for CO2

When human emissions of CO2 enter the atmosphere, some of that gas is absorbed by the ocean, slowing the rise in global temperature and climate change. Cold water from the deep ocean rises to the surface through a process called upwelling. Once at the surface, that colder water absorbs CO2 in the atmosphere – often with the help of photosynthesizing organisms called phytoplankton – before sinking again.

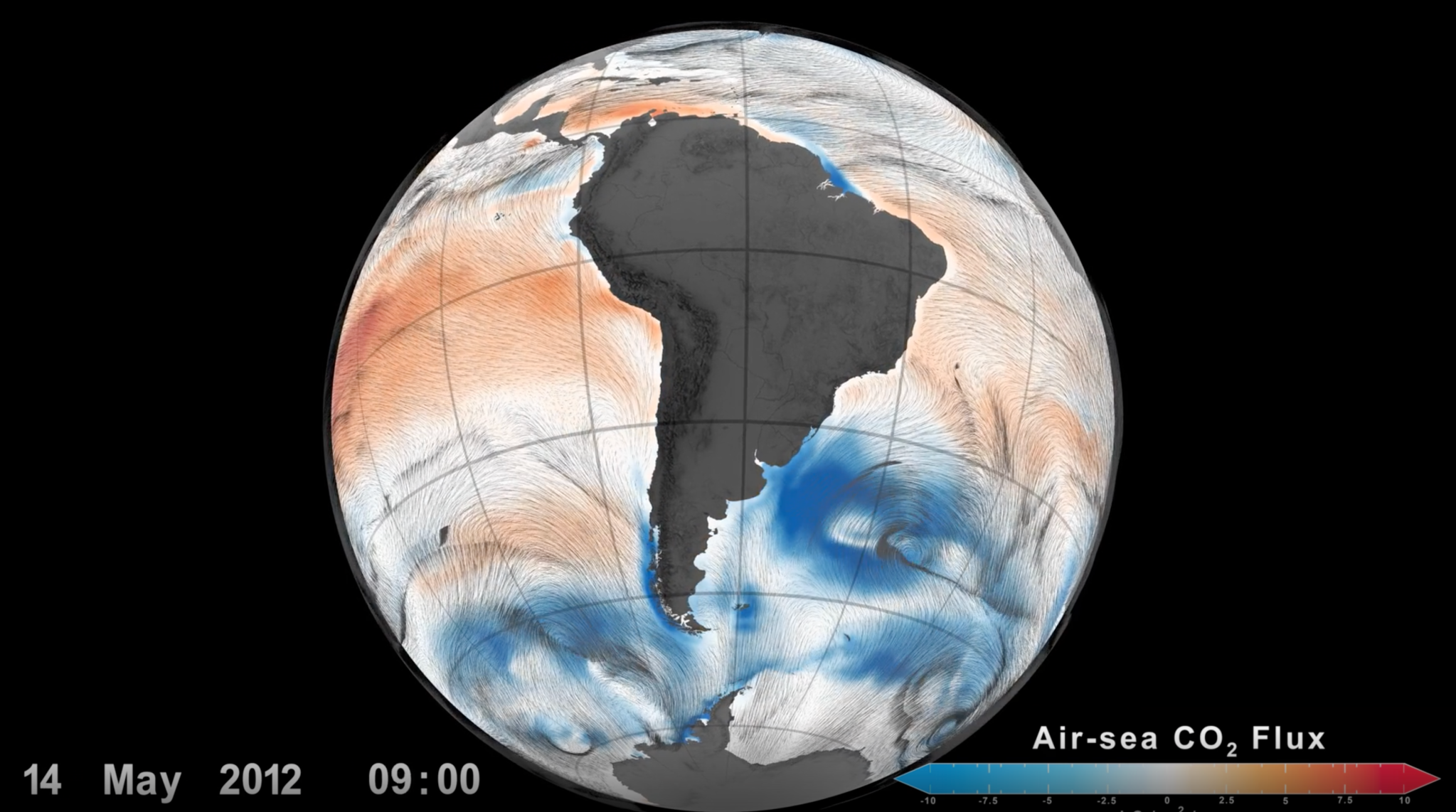

Computer models based on measurements of CO2 and other ocean properties suggest that 40% of the human-produced CO2 in the ocean, worldwide, was originally absorbed from the atmosphere into the Southern Ocean, making it one of the most important carbon sinks on our planet. But measuring the flux, or exchange, of CO2 where the air meets the sea has been challenging.

In this study, the team used airborne measurements from three field experiments: ATom, HIPPO and ORCAS. Collectively, these projects captured a critical piece of information: the vertical gradient of CO2 in the atmosphere. For example, during the ORCAS campaign in early 2016, scientists saw a drop in CO2 concentrations as the plane descended and high turbulence near the ocean surface, suggesting an exchange of gases like CO2 between the air and ocean.

Taking measurements of CO2 over the course of several field experiments flying above the Southern Ocean gave the scientists a series of snapshots of the vertical change in CO2 (called profiles) over time and throughout the seasonal carbon cycle. These profiles, along with a suite of several atmospheric computer models, helped the team estimate the flux of how much CO2 was being absorbed and released by the Southern Ocean throughout the year.

Credits: Chelsea Thompson, NOAA

For more information about NASA’s Airborne Science programs, visit: https://airbornescience.nasa.gov/

By Sofie Bates