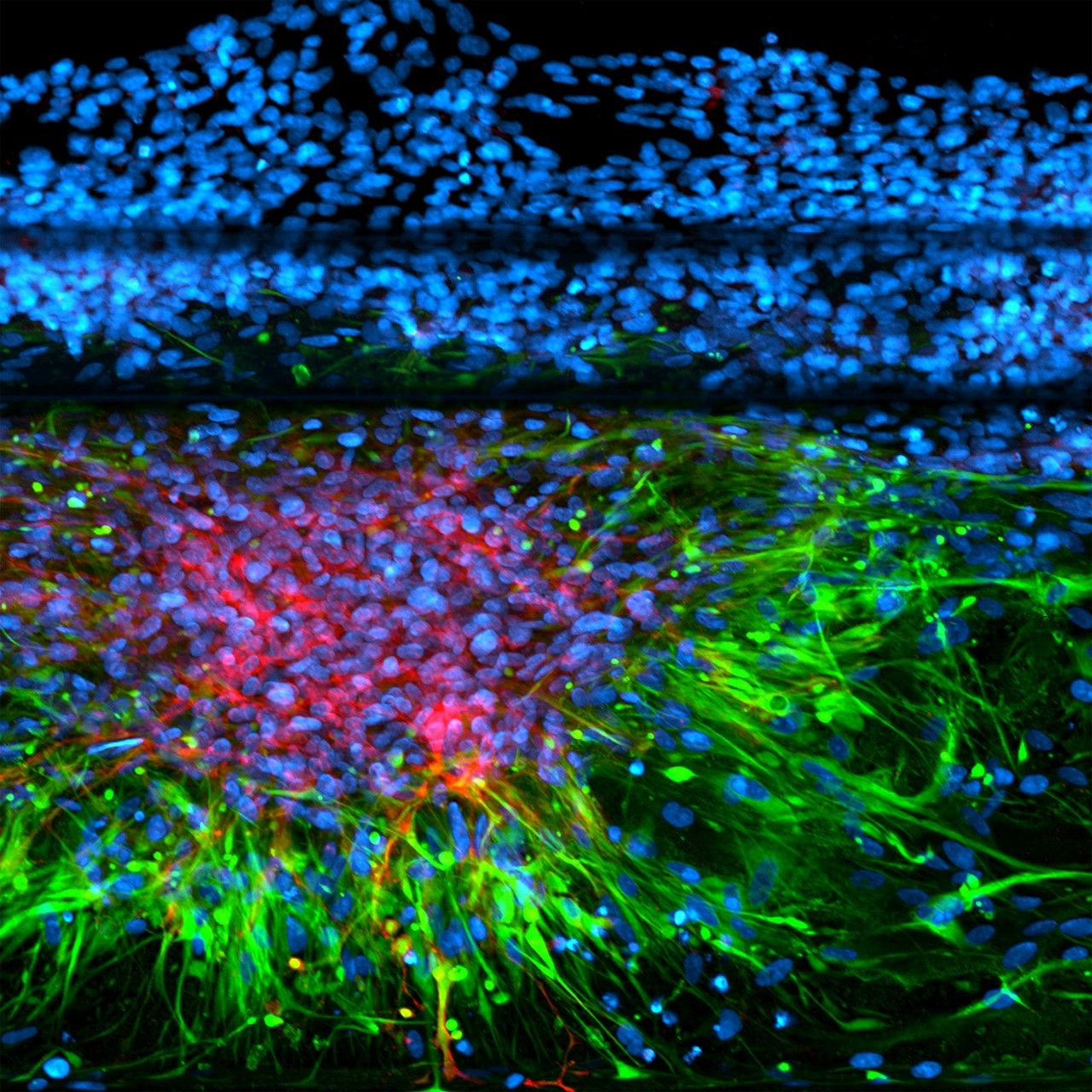

NASA is preparing to send astronauts on journeys that will include longer stretches in microgravity – to the Moon and onward to Mars. Understanding how basic biology works in space will help astronauts adapt and thrive during long duration missions. To better understand how space affects astronauts, researchers often study other model organisms, like mice, whose biology has similarities to human body systems.

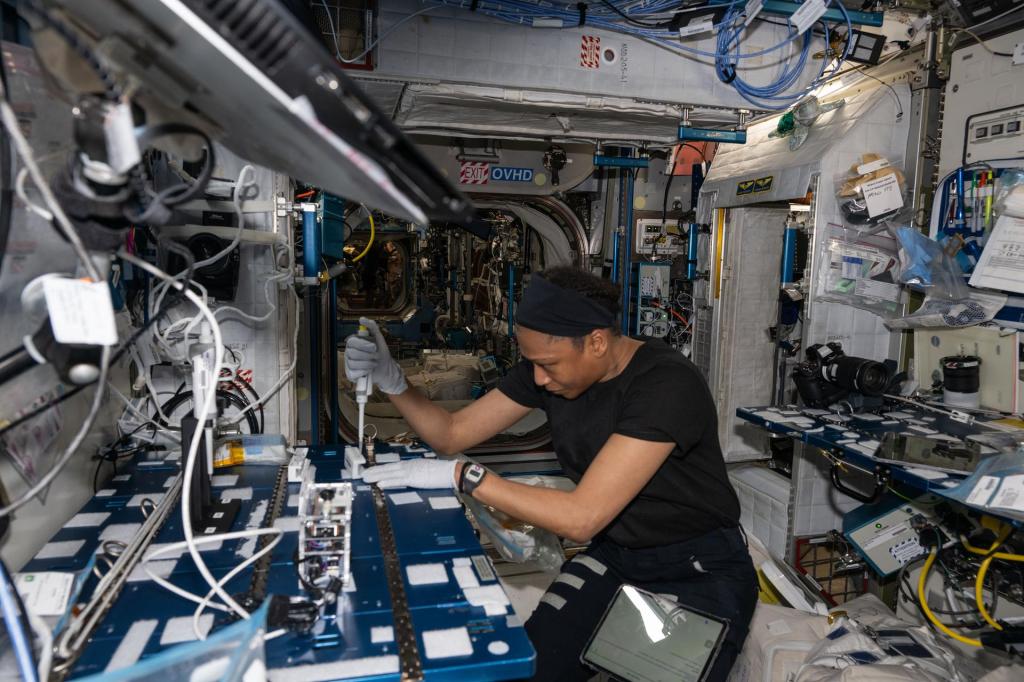

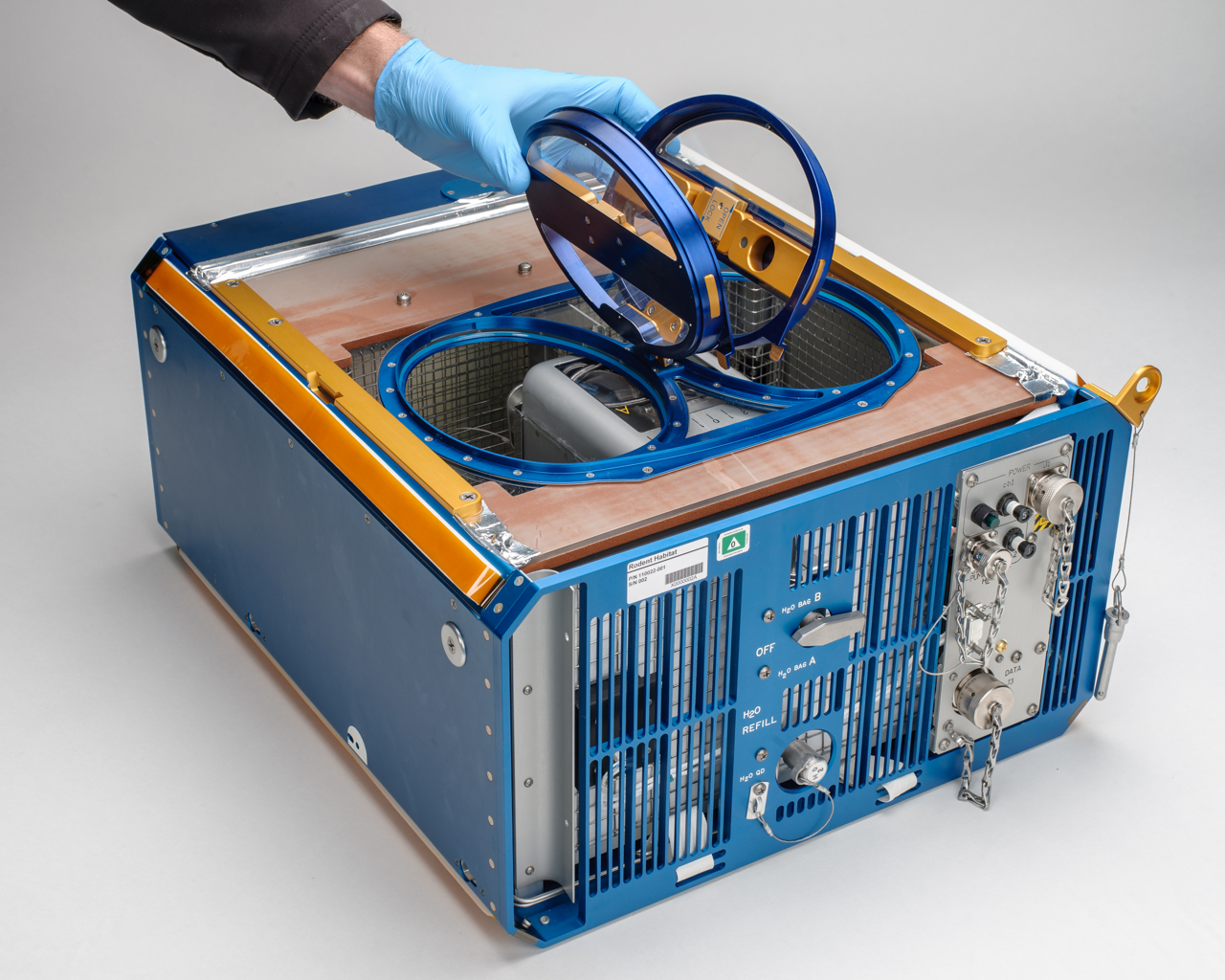

NASA scientists have now published the first detailed study of how mice behave in the NASA Rodent Hardware System, which has housed almost a dozen experiments on the International Space Station since 2014. They found that the rodents engaged in all the typical mouse behaviors, even in the “weightlessness” of the microgravity environment.

“Behavior is a remarkable representation of the biology of the whole organism,” said April Ronca, a researcher at NASA’s Ames Research Center in California’s Silicon Valley, and lead author of the paper. “It informs us about overall health and brain function.”

Business Mostly as Usual for Mice in Space

In this study, scientists examined video recordings of mice and compared their activity to that of mice that stayed on Earth. The total study duration included 37 days in microgravity – a long-duration mission on the scale of the rodent life span.

The results showed that the spaceflight mice did all the things they normally would: feeding, grooming their fur, huddling together and interacting with other mice. The rodents quickly adapted to their new weightless circumstances, for example by anchoring themselves to the habitat walls with their hindlimbs or tails and stretching out their bodies. This pose was similar to mice on Earth standing up on their back legs to explore their environment.

Throughout their time aboard the space station, the mice actively explored the entire habitat. At the end of the study, they weighed about the same as the Earth-based group and their coats were in excellent condition – both signs of good health.

A unique behavior was seen in some mice, starting about a week after launch. The study included groups of younger and older females, and the younger mice in space were more physically active than their counterparts on the ground. The younger group also began to show a new behavior that the scientists describe as “race-tracking” – running laps around the cage. This even evolved into a group activity.

Scientists don’t yet know the reasons for this group circling behavior. It could be that the physical exercise itself was rewarding for the mice, that the behavior was a stress response, or that the motion provided stimulation to the body’s balance system, which is mostly absent in microgravity. The researchers think stress is less likely to be the cause – the mice behaved normally otherwise and were in excellent health – but more research is needed to know for sure.

For the moment, even knowing about the circling will be helpful for other studies of mouse physiology in space. For example, other scientists might now take into consideration increased blood flow from the rodents’ extra activity.

A Useful Comparison “of Mice and Men”

Unlike other rodent housing flown in space, the mice in this study were able to grab hold of things and to run inside NASA’s rodent habitat. That physical activity matters when scientists are studying the effect of microgravity on bone loss, for example, and need the animals to be able to move around in ways similar to humans. The habitat provides a useful basis for comparison of mice and humans for a better understanding of human responses to spaceflight.

The new study has helped to establish NASA’s system as a capability for conducting long-duration rodent studies in space. Its findings will also inform the other spaceflight experiments in the Rodent Research series, which are now analyzing their results.

“Our behavioral study shows that the NASA Rodent Hardware System provides the capability to conduct meaningful long-duration biological research studies on the International Space Station,” said Ronca. “Experiments conducted in the habitat can focus on how mouse physiology responds to the spaceflight environment during extended missions and on similarities in response to astronaut crew.”

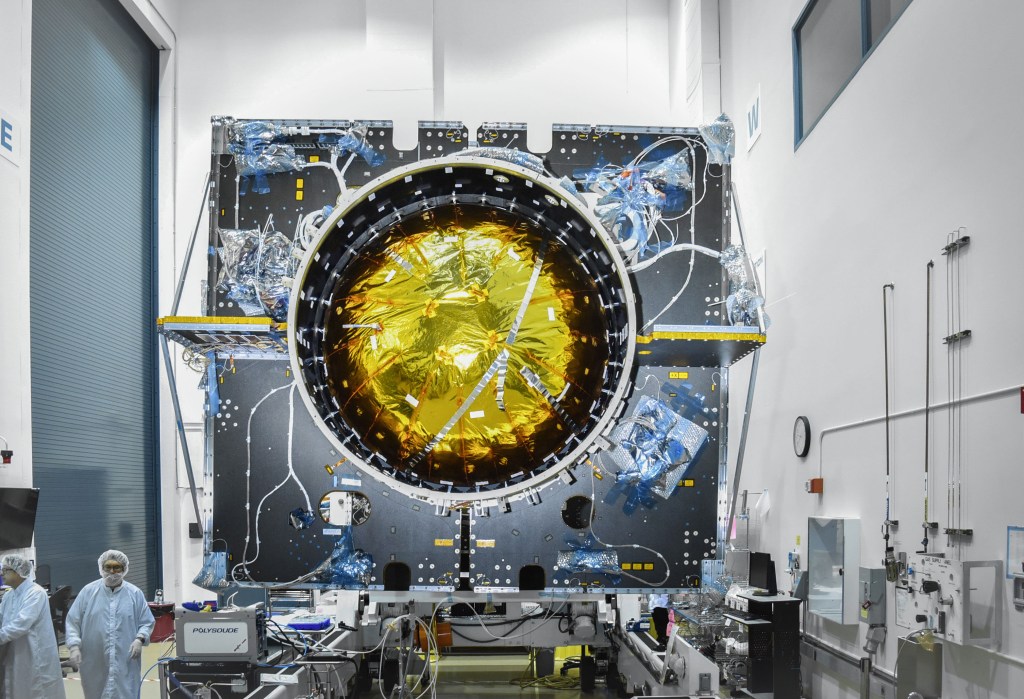

The hardware system was designed at Ames, to make research like this possible in space. The study’s results were published online in the journal Scientific Reports on April 11, 2019, using data from the Rodent Research-1 mission. The Novartis Institutes for Biomedical Research and the Center for the Advancement of Science in Space collaborated with NASA on the study.

For news media:

Members of the news media interested in covering this topic should contact Alison Hawkes at alison.hawkes@nasa.gov.