The History of Ames Research Center

Basic and applied research have been cornerstones of the work at NASA's center in the Silicon Valley of California since its founding as an aeronautical laboratory in December of 1939.

The NACA’s Second Laboratory

NASA’s Ames Research Center evolved as a unique place where state-of-the-art facilities and world-class talent melded to produce cutting-edge research in fields such as aerodynamics, thermodynamics, simulation, space and life sciences, and intelligent systems. The center’s contributions have fundamentally shaped fields of study related to aeronautics and space. The ingenuity and problem-solving capabilities of personnel at Ames have affected all our lives in numerous ways, from everyday air travel to how we envision the possibility of life on other worlds.

Established in 1939 as the work of the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA) expanded, the new laboratory at Moffett Field was named in honor of Joseph Sweetman Ames, a chairman of the NACA and former provost and president of the Johns Hopkins University. On December 20, 1939, just two months after a committee chaired by Charles Lindbergh selected the location, ground was broken to inaugurate the construction of the new laboratory. Before the NACA officially approved the name of Ames Aeronautical Laboratory on March 12, 1940, the site was known simply as an expansion of the NACA’s first laboratory.

The First Facilities

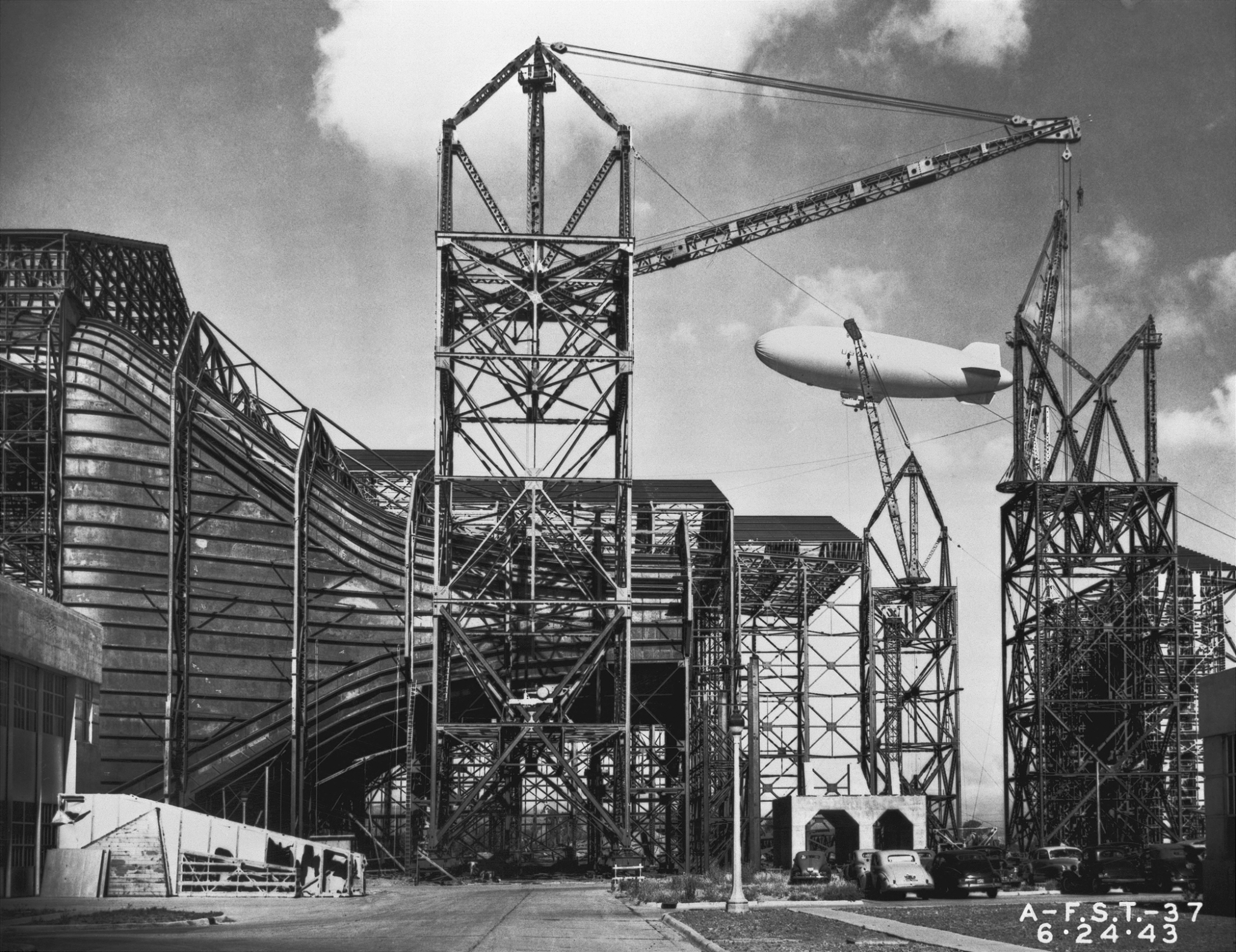

A wooden shack served as the office for planning the construction of the first facilities at Ames. The first facilities included a flight research hangar and a few wind tunnels. The expansion beyond the NACA’s first laboratory was necessary since that laboratory, present day Langley Research Center, had run out of available space and was experiencing a shortage of adequate electrical power at the time. A new site was essential for the continued development of aeronautical research in the United States.

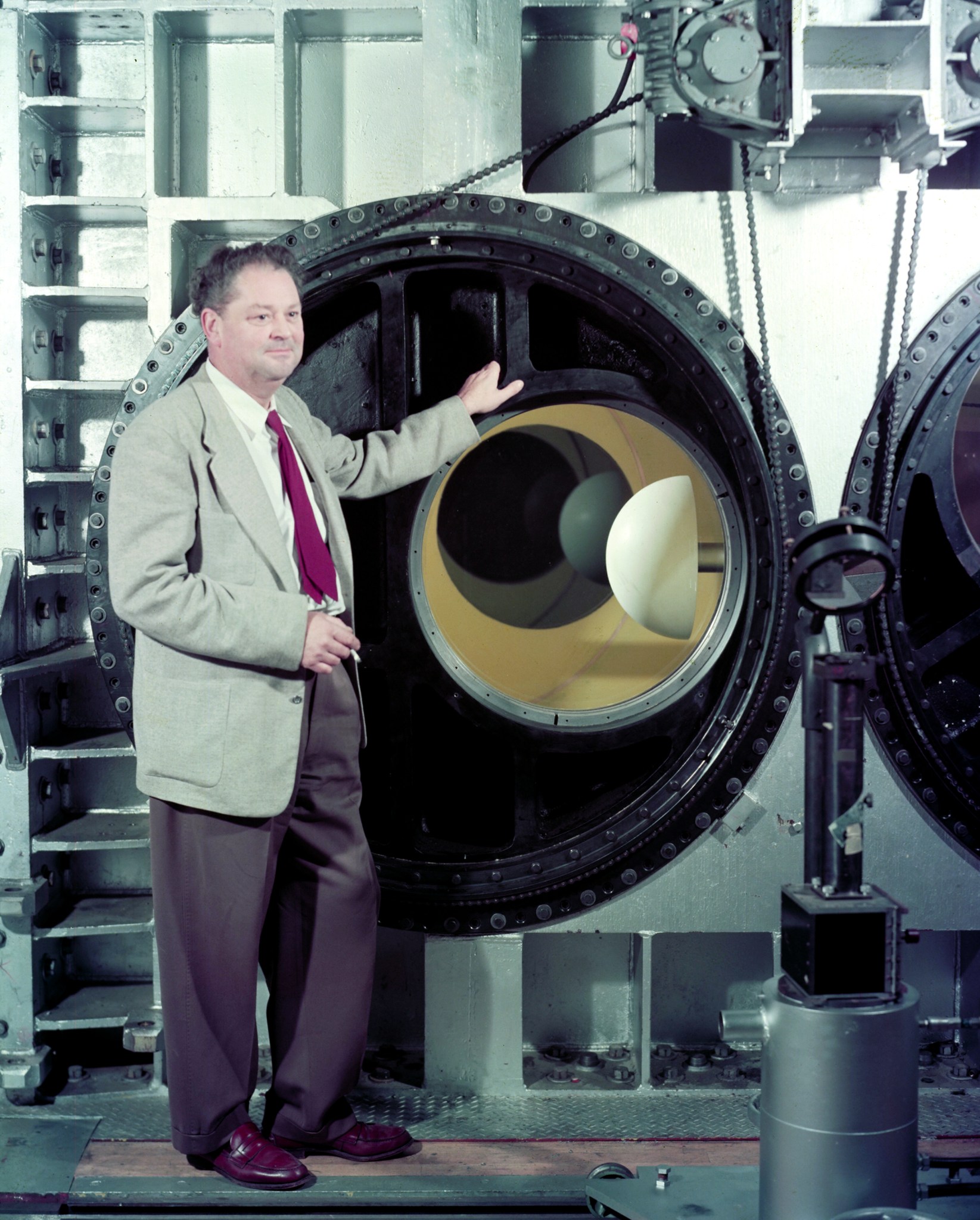

Building upon the innovative wind tunnels that the NACA had designed over the previous two decades, the NACA’s aeronautical engineers at Ames built new, cutting-edge tunnels that included the world’s largest (what became the National Full-Scale Aerodynamics Complex) and one of the fastest (the 16-Foot High Speed Tunnel). These facilities and the testing they enabled made quick, practical, and crucial design changes possible. In its early years backdropped by World War Two, the center provided civilian expertise and infrastructure vital to improving America’s military air power. In the decades that followed, nearly every American aircraft has been tested in one way or another at Ames.

Aeronautics

The early years at Ames were devoted to testing the limits of aeronautical theory with wind tunnels and flight research. As supersonic flight became a reality in the late 1940s, Ames researchers devised new theoretical insights that informed the design of aircraft, making supersonic flight more efficient.

At even higher speeds, thermodynamics becomes important since hypersonic objects can burn up like a meteor in the atmosphere. Known as the heating problem, one of the most enduring and counterintuitive innovations to come out of Ames to solve this problem is the blunt body concept. In 1953, researchers at Ames published a paper suggesting a blunt shape for a vehicle returning from space that would help prevent it from burning up in Earth’s atmosphere. A blunt tip changed how the atmosphere around the vehicle—whether a missile or a crewed spacecraft—became hot. This would prove crucial for returning astronauts safely to Earth even though the solution had initially come from missile design.

The blunt body concept has since informed the development of lifting bodies, the design of the space shuttle, and it is still incorporated into the capsules and probes that must survive atmospheric entry, whether on Earth or on other worlds.

Science

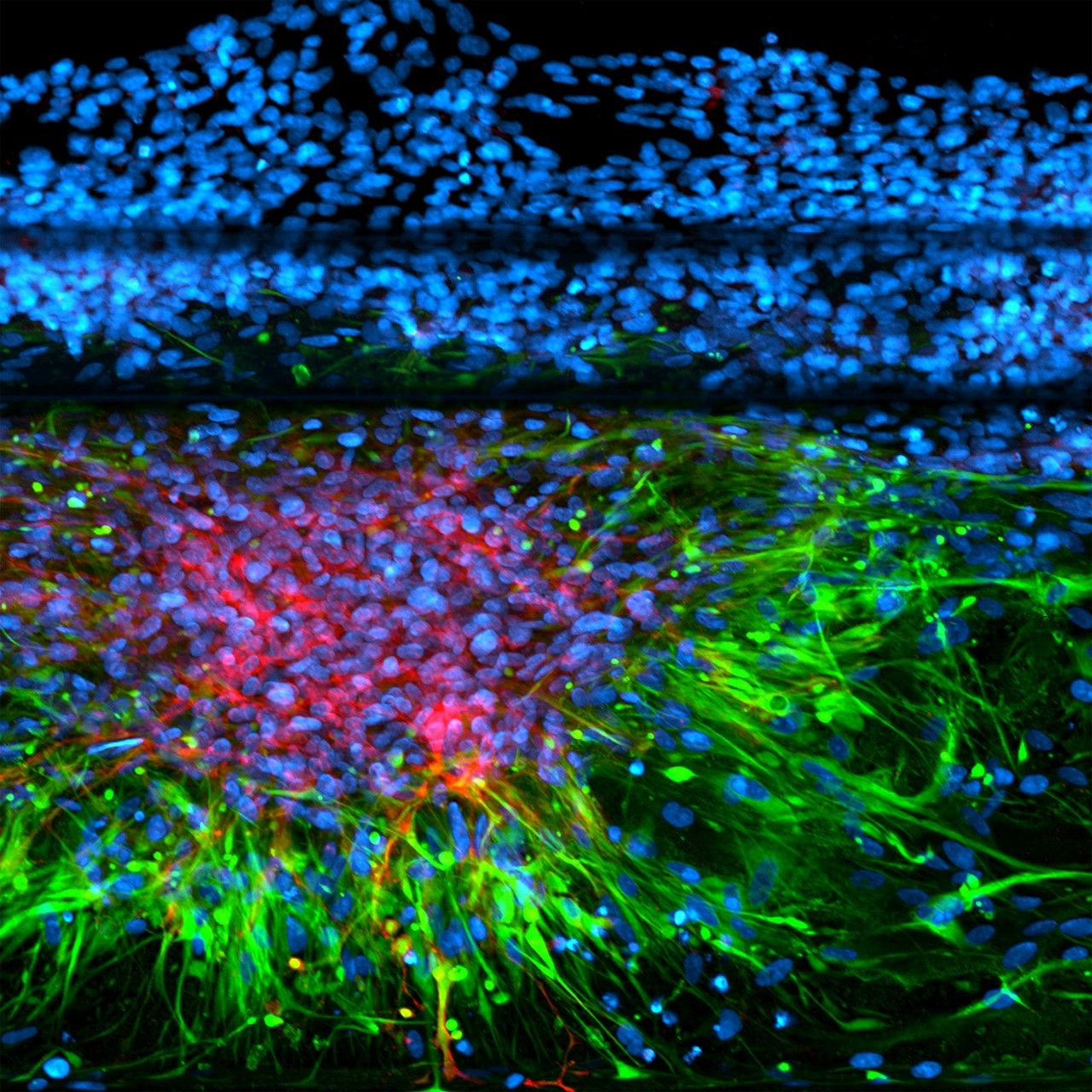

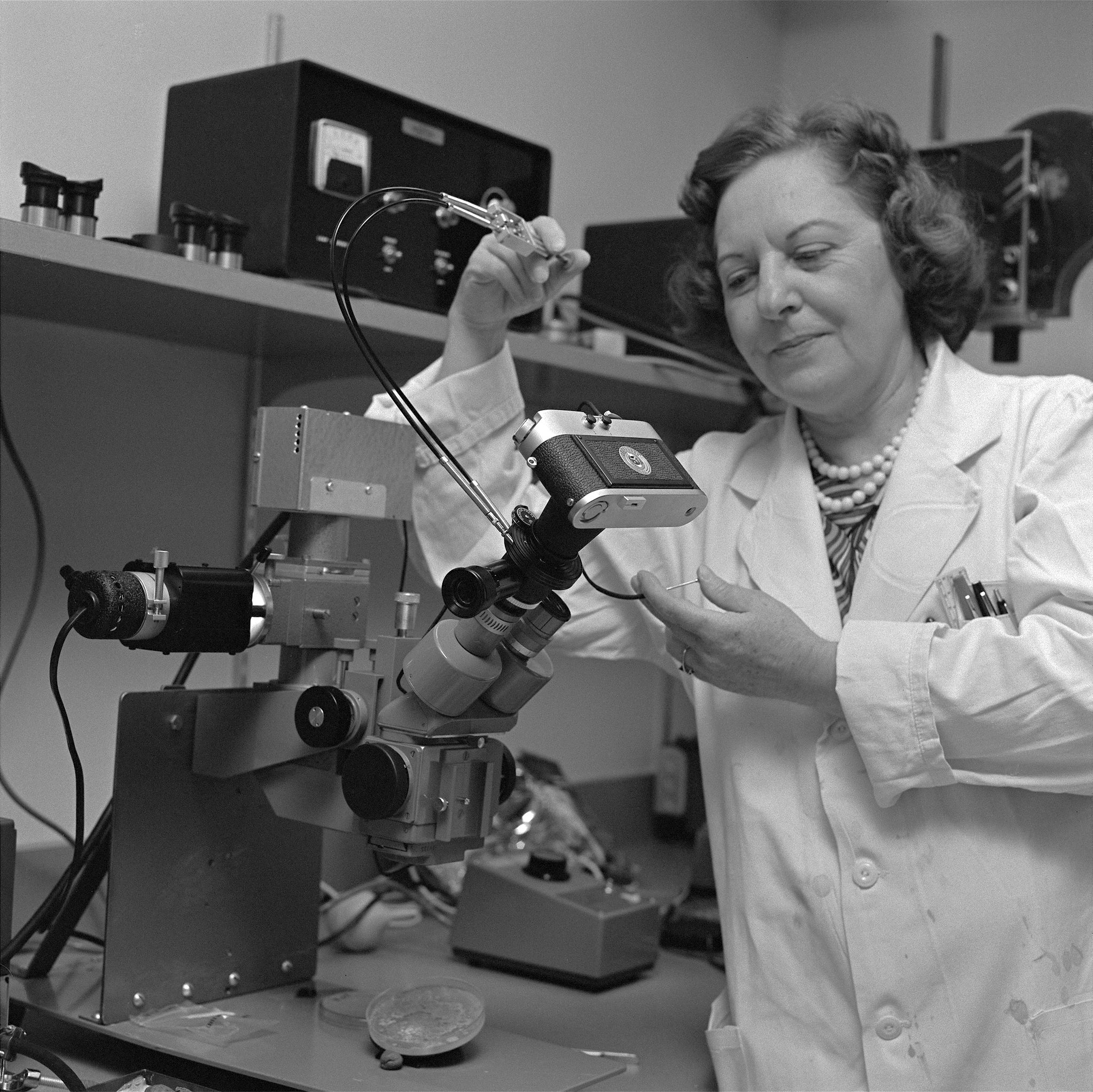

Science at Ames holds a unique place within NASA. Almost as soon as NASA was founded, the agency began developing plans for studying biological sciences in the context of space travel. After a competitive search for where to establish expertise in the space life sciences for the agency, NASA selected Ames. Ames thus became an early leader in studying life in extreme environments and searching for life beyond Earth.

Ames researchers were among the first to inspect lunar samples and check for signs of life when Apollo 11 returned from the Moon. Ames led the biology team for NASA’s Viking mission that successfully landed on Mars and returned a wealth of chemical data from the surface of the Red Planet. While the results of Viking could not confirm any signs of life, life sciences research at Ames expanded beyond studying exobiology and the effects of gravity on living organisms to encompass more biomedical research, ecosystem science and technology, and advanced life support systems. Beginning in the 1990s, Ames led the development of virtual institutes for NASA for two decades, leveraging the most effective information and communications technology to enable collaborative and interdisciplinary research across institutional and geographic boundaries. This shaped and strengthened the scientific community as the new interdisciplinary field of astrobiology developed.

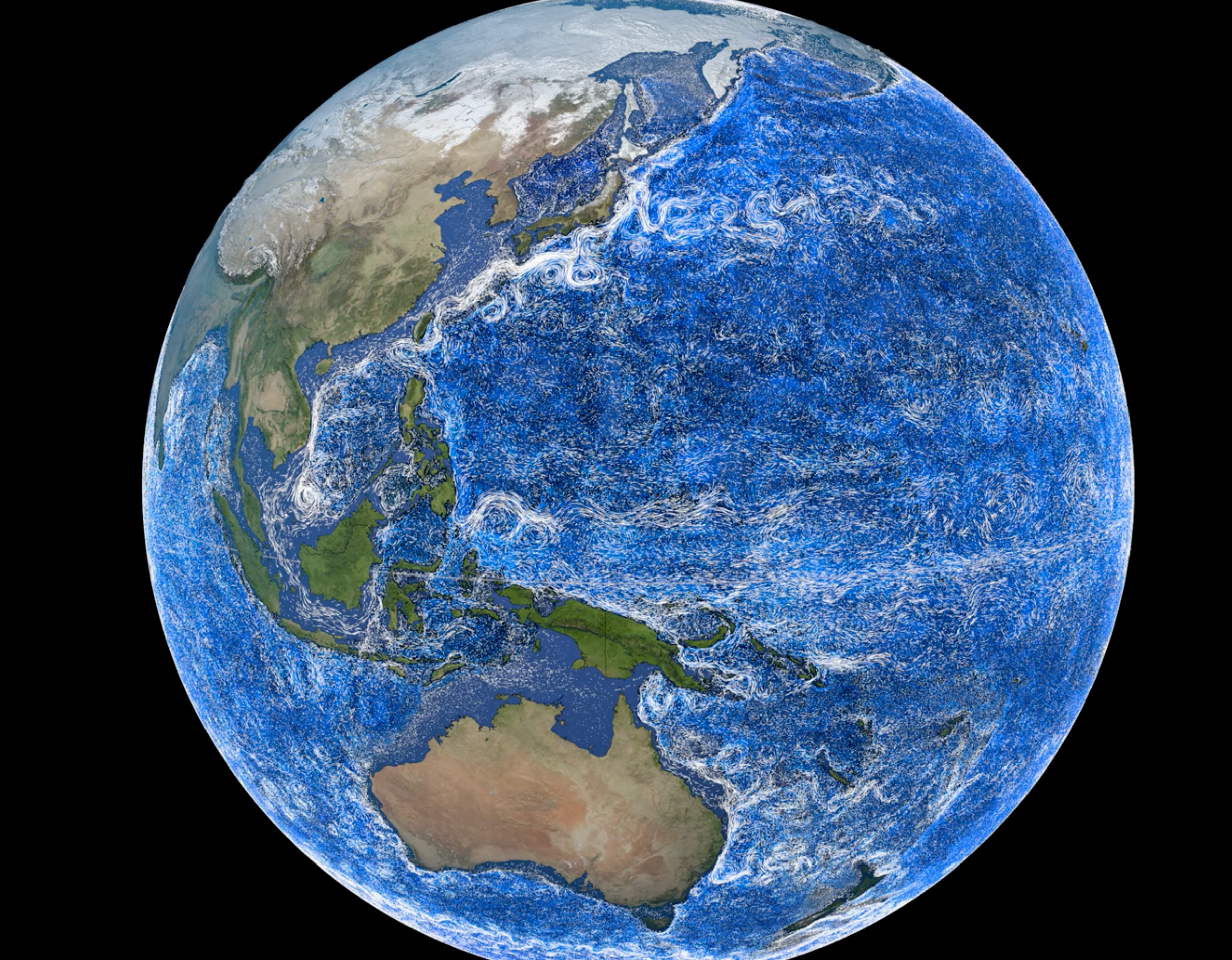

In addition to the life sciences, other multidisciplinary efforts have driven the interplay between observation and experimental data, leading to new mission concepts and the development of new technologies and instrumentation. Space and Earth science activities have long histories at Ames, including airborne astronomy efforts such as the Kuiper Airborne Observatory and SOFIA as well as Earth science applications including studies conducted from U-2s and ER-2 aircraft. These and similar airborne science platforms have enabled decades of timely and cutting-edge research, from mapping croplands and soils to studying how land interacts with the atmosphere.

Spaceflight Missions

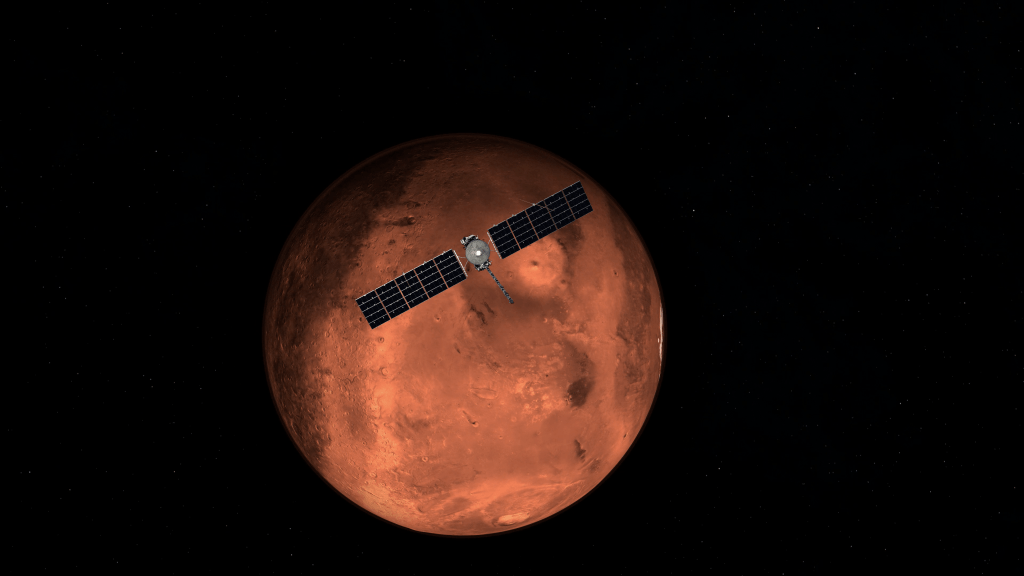

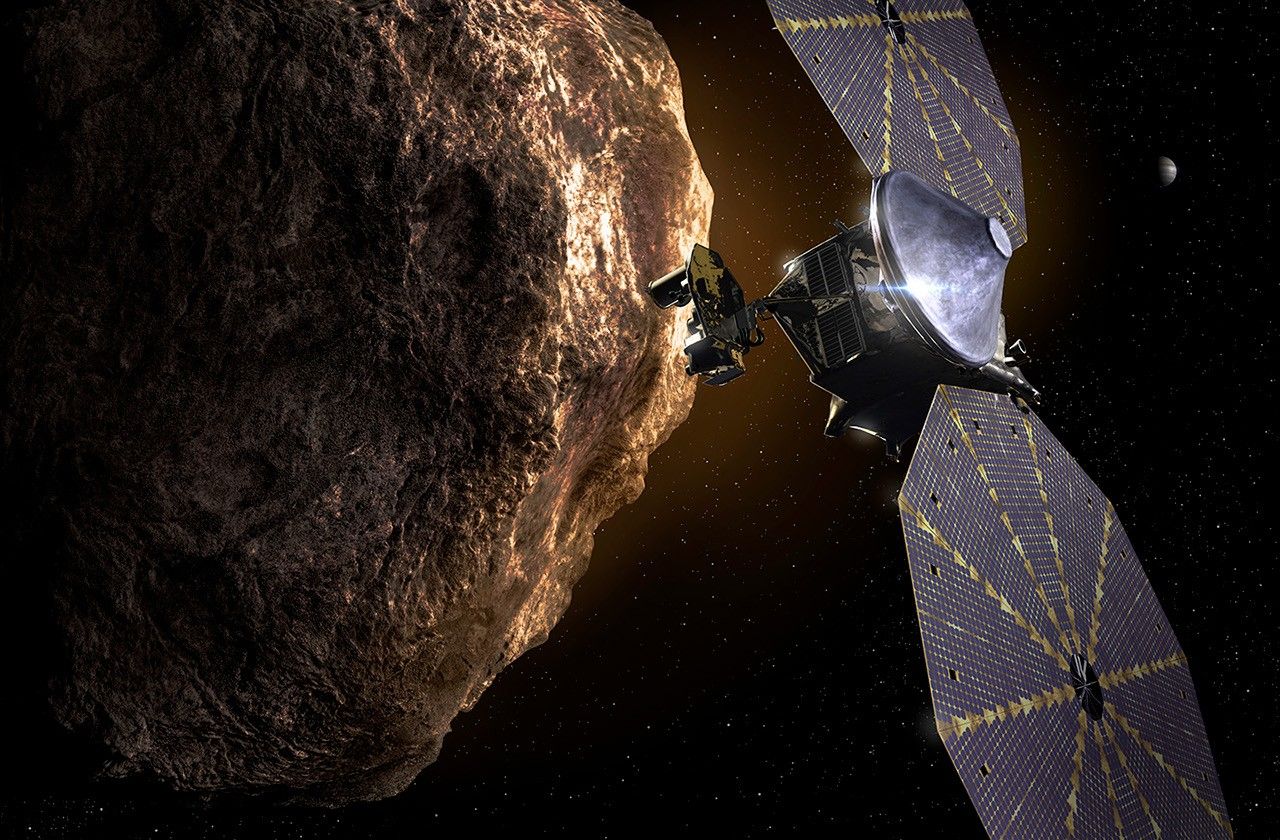

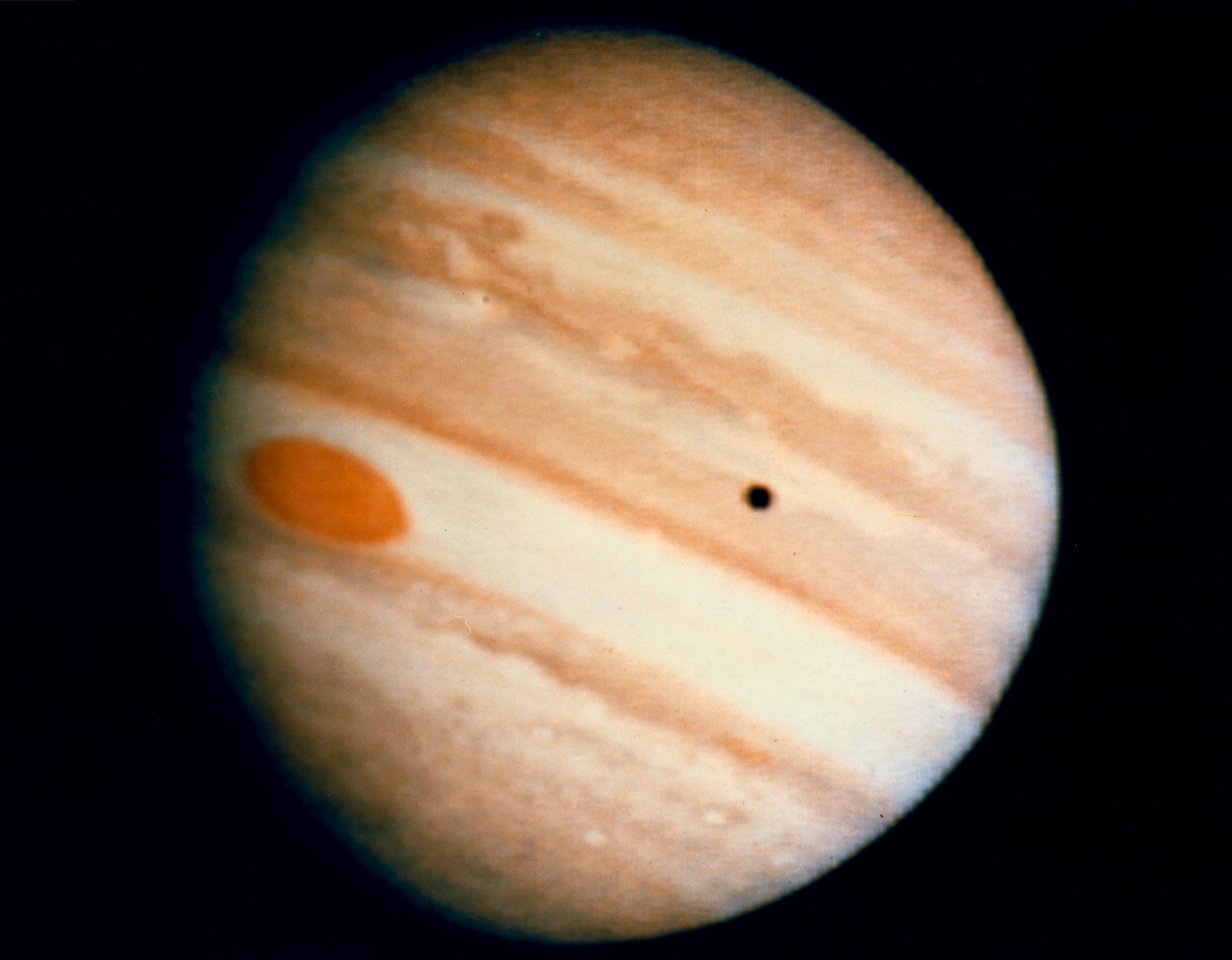

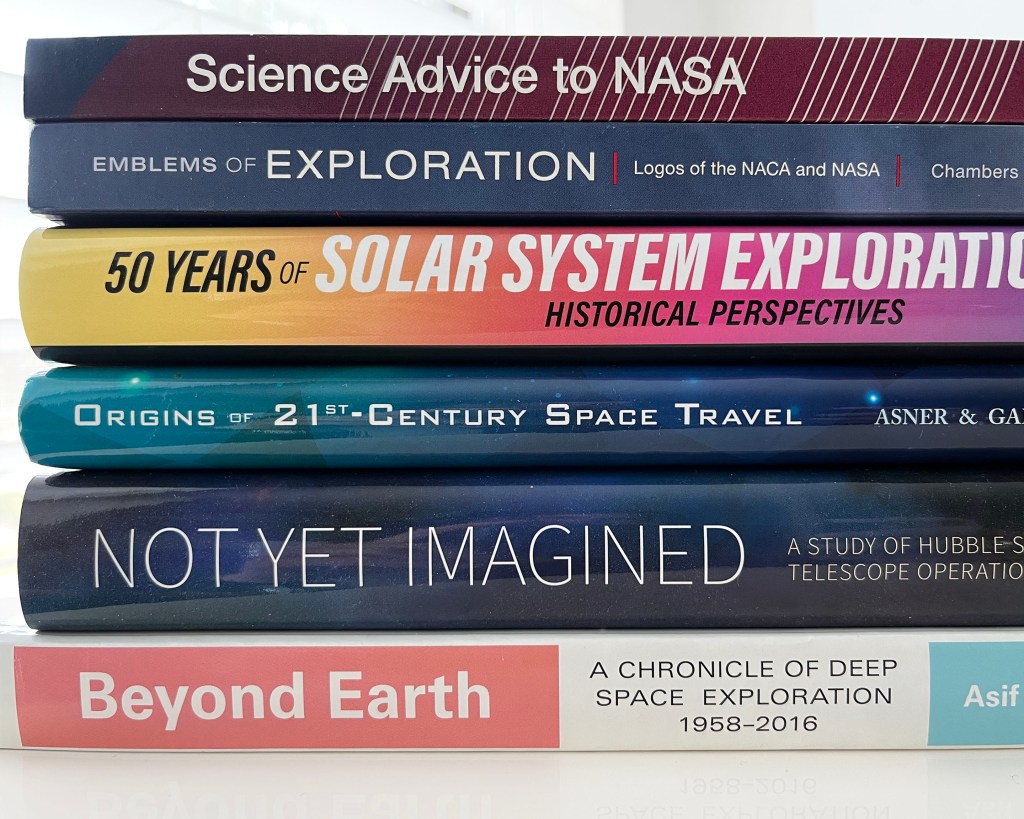

Ames-led missions in space have achieved historic firsts. In the 1960s, Ames managed Pioneers 6 through 9, which became the first space-based solar weather-monitoring network. Ames continued the program with Pioneers 10 and 11, the first two of only five spacecraft that have been sent on trajectories that will leave the solar system. Following Pioneer 11, the Pioneer Venus mission sent an orbiter and probes to explore Venus. Ames later managed the Galileo probe, the first spacecraft to enter Jupiter’s atmosphere. Entry systems remain an area of Ames expertise, enabling NASA’s missions to learn more about other worlds in our solar system.

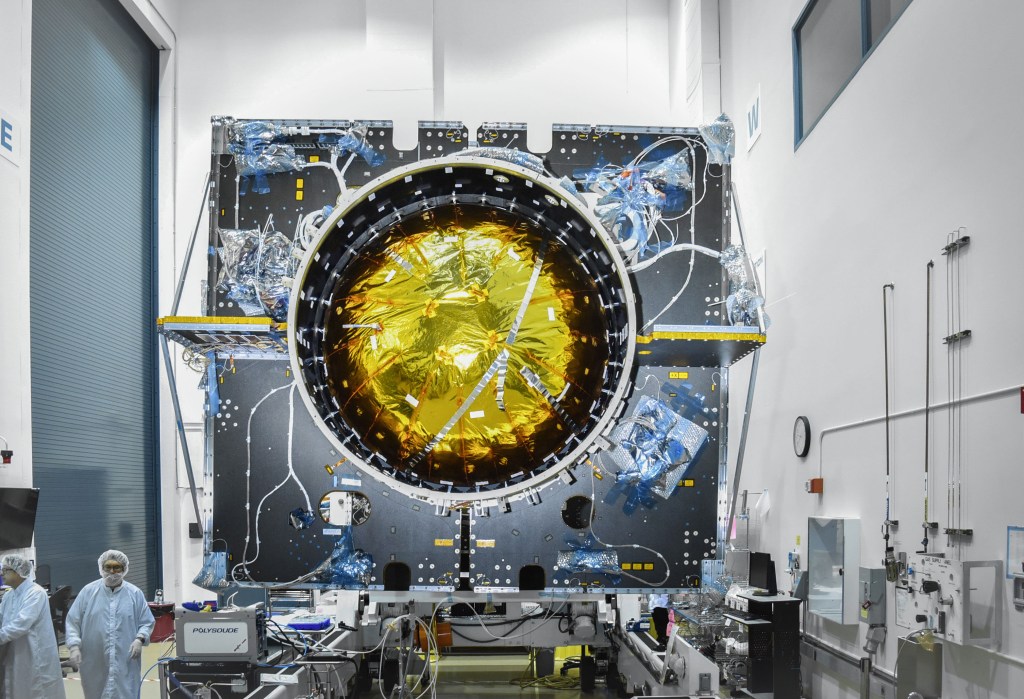

The continuing standardization of spacecraft architecture and the greater prevalence of commercially available hardware suitable for spaceflight have contributed to the proliferation of small spacecraft. The first Ames nanosatellite, GeneSat, launched in 2006 and successfully demonstrated the feasibility of a life sciences experiment using microscopic fluid flow technology in space.

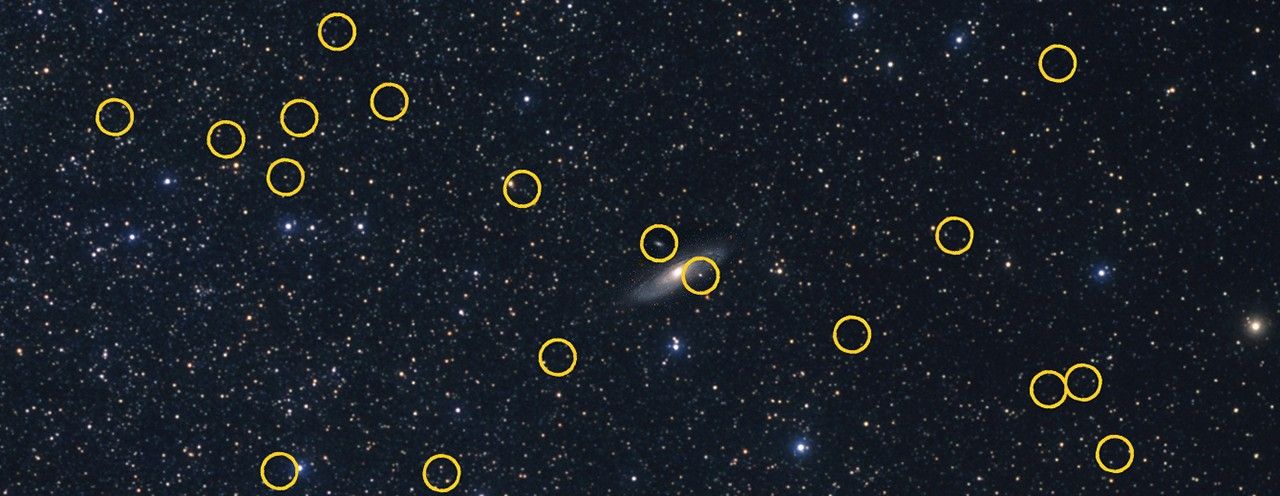

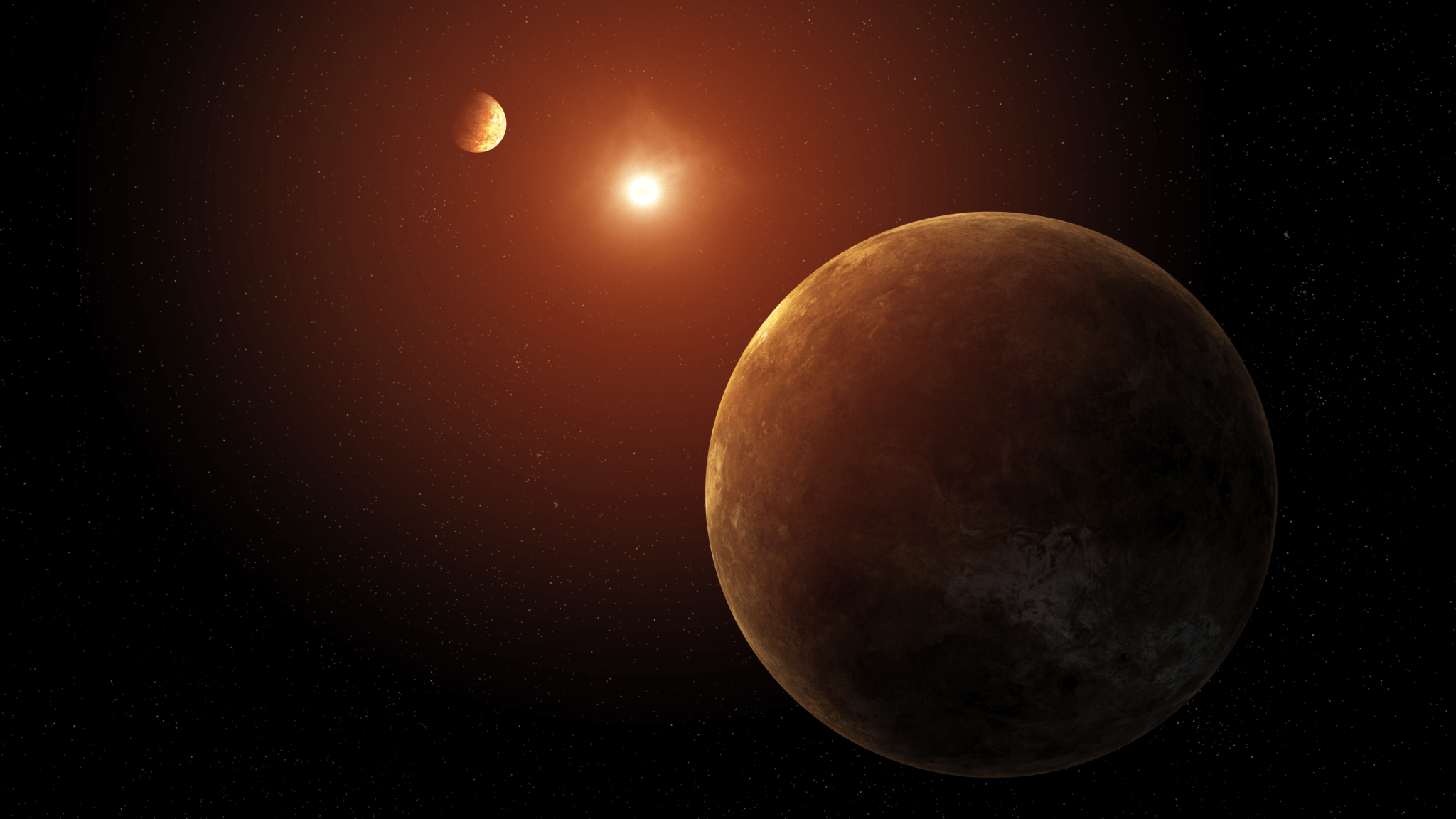

Beyond our own solar system, astronomers discovered the first exoplanet in orbit around a Sun-like star in 1995. Ames developed the mission and led the science for the Kepler space telescope. When Kepler launched in 2009, it became NASA’s first mission that could find Earth-size planets within the habitable zones of other stars. Kepler discovered more than 2,600 worlds before the spacecraft was retired in late 2018. Based on Kepler’s data, we have learned that there are more planets than stars in our galaxy.

Ames researchers have long contributed to our understanding of our nearest celestial neighbor, the Moon. For decades, there was no evidence to suggest that there could be water on the Moon. That changed in the 1990s. After the Clementine mission in 1994 found faint hints of what could be water ice on the Moon, Ames led the Lunar Prospector mission, the first lunar mission ever launched on a commercially developed rocket. The high hydrogen levels at the poles that Lunar Prospector found strongly suggested the presence of water ice. Ames’s Lunar Crater Observation and Sensing Satellite, or LCROSS, confirmed Lunar Prospector’s findings. Confirming water ice at the south pole of the Moon has changed our perception of what is possible on the Moon. Ames-led missions to refine our understanding followed, including LADEE, the Lunar Atmosphere and Dust Environment Explorer, and Ames instruments have flown on Commercial Lunar Payload Services (CLPS) missions.

Supercomputing

As the nascent Silicon Valley grew up around the center, Ames initially kept pace with acquiring and leveraging the latest in computer technology. The first electronic computer arrived at Ames in 1949, an early milestone in the later development of flight simulators at the center. Ames staff realized they could use the reprogrammable capability of those early analog computers to test a wide variety of configurations for aircraft, all from the ground. The flexibility of reprogramming a simulator was further strengthened with the development of interchangeable cabs, the structures that recreate the cockpit environment. That flexibility allows testing not just of existing aircraft and spacecraft, but any theoretical design for future use.

Advances in computing supported the demanding computations involved in aeronautics research, in addition to spaceflight applications. But as the pace of computer development increased in the 1960s, Ames was unable to keep up. The center simply could not buy new computers every time one was released. As the Apollo program was winding down and other, newer NASA centers could acquire new computers, Ames had fallen behind. That lapse was temporary. In the early 1970s, Ames’s third director, Hans Mark, took action that set Ames on its path to becoming the preeminent NASA center for supercomputing. Beyond raw computing power, Ames applied NASA’s new computing capabilities to, perhaps most significantly, advance the state-of-the-art as a continuing world leader in computational fluid dynamics.

From its roots as an aeronautical laboratory of the NACA to a research center within NASA, Ames has inherited a rich past that informs the future and contributes to the success of NASA’s mission.