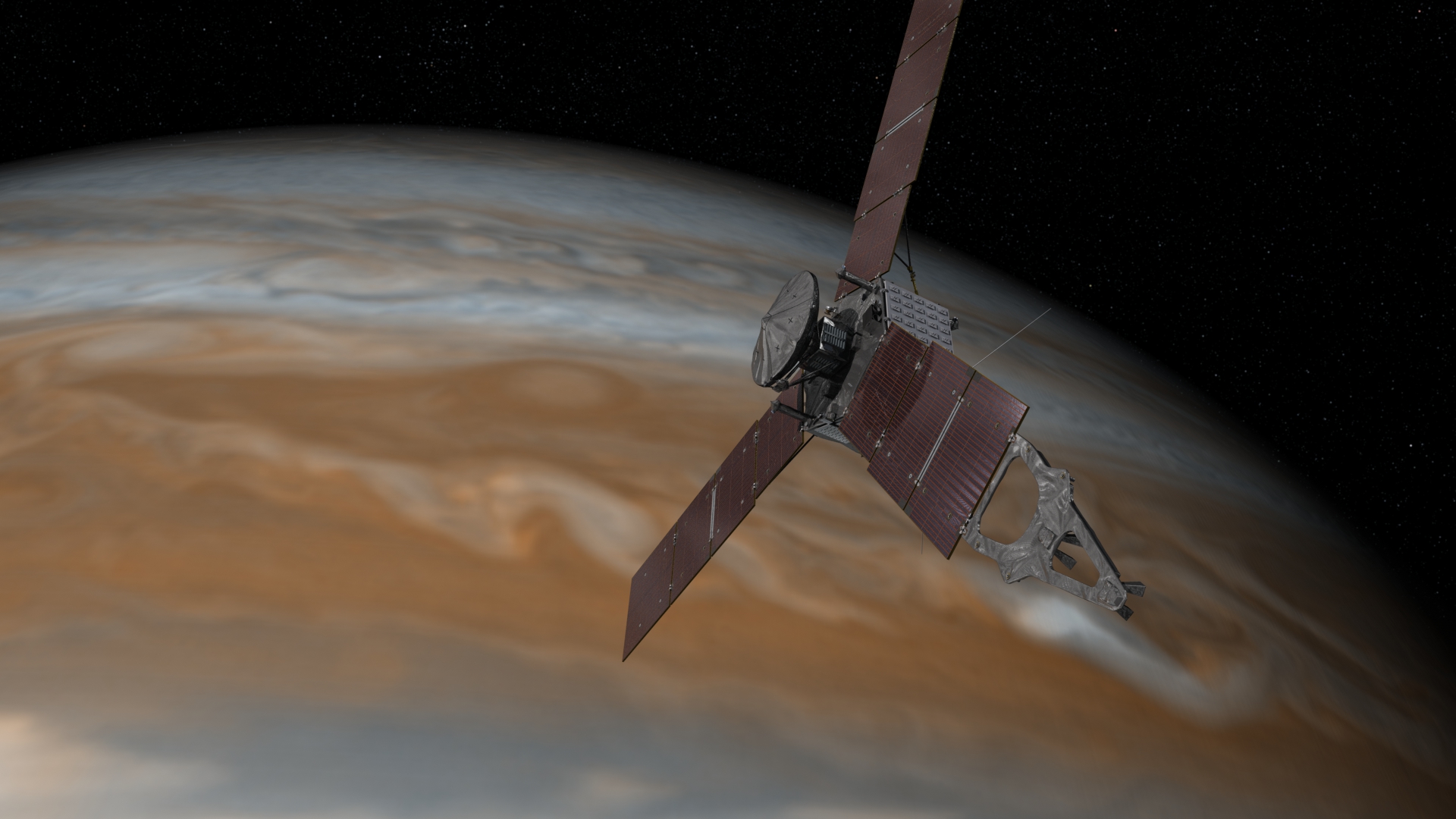

On July 4, NASA will fly a solar-powered spacecraft the size of a basketball court within 2,900 miles (4,667 kilometers) of the cloud tops of our solar system’s largest planet.

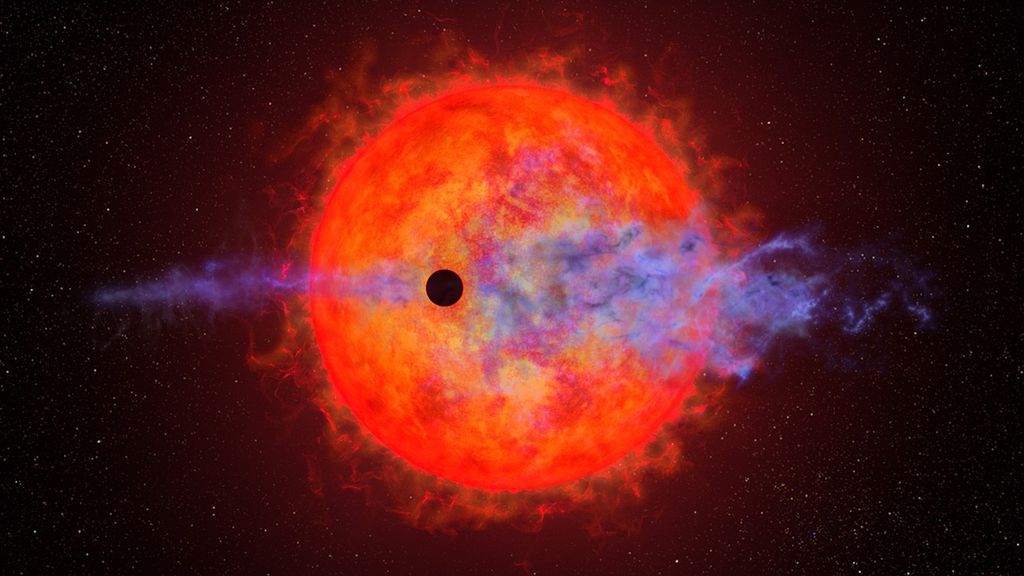

As of Thursday, Juno is 18 days and 8.6 million miles (13.8 million kilometers) from Jupiter. On the evening of July 4, Juno will fire its main engine for 35 minutes, placing it into a polar orbit around the gas giant. During the flybys, Juno will probe beneath the obscuring cloud cover of Jupiter and study its auroras to learn more about the planet’s origins, structure, atmosphere and magnetosphere.

“At this time last year our New Horizons spacecraft was closing in for humanity’s first close views of Pluto,” said Diane Brown, Juno program executive at NASA Headquarters in Washington. “Now, Juno is poised to go closer to Jupiter than any spacecraft ever before to unlock the mysteries of what lies within.”

A series of 37 planned close approaches during the mission will eclipse the previous record for Jupiter set in 1974 by NASA’s Pioneer 11 spacecraft of 27,000 miles (43,000 kilometers). Getting this close to Jupiter does not come without a price — one that will be paid each time Juno’s orbit carries it toward the swirling tumult of orange, white, red and brown clouds that cover the gas giant.

“We are not looking for trouble, we are looking for data,” said Scott Bolton, principal investigator of Juno from the Southwest Research Institute in San Antonio. “Problem is, at Jupiter, looking for the kind of data Juno is looking for, you have to go in the kind of neighborhoods where you could find trouble pretty quick.”

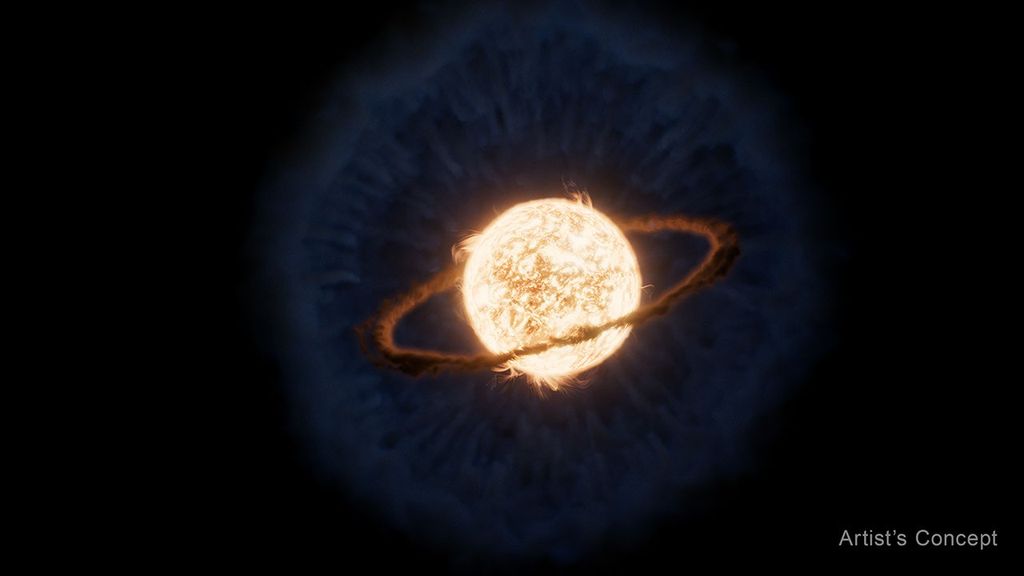

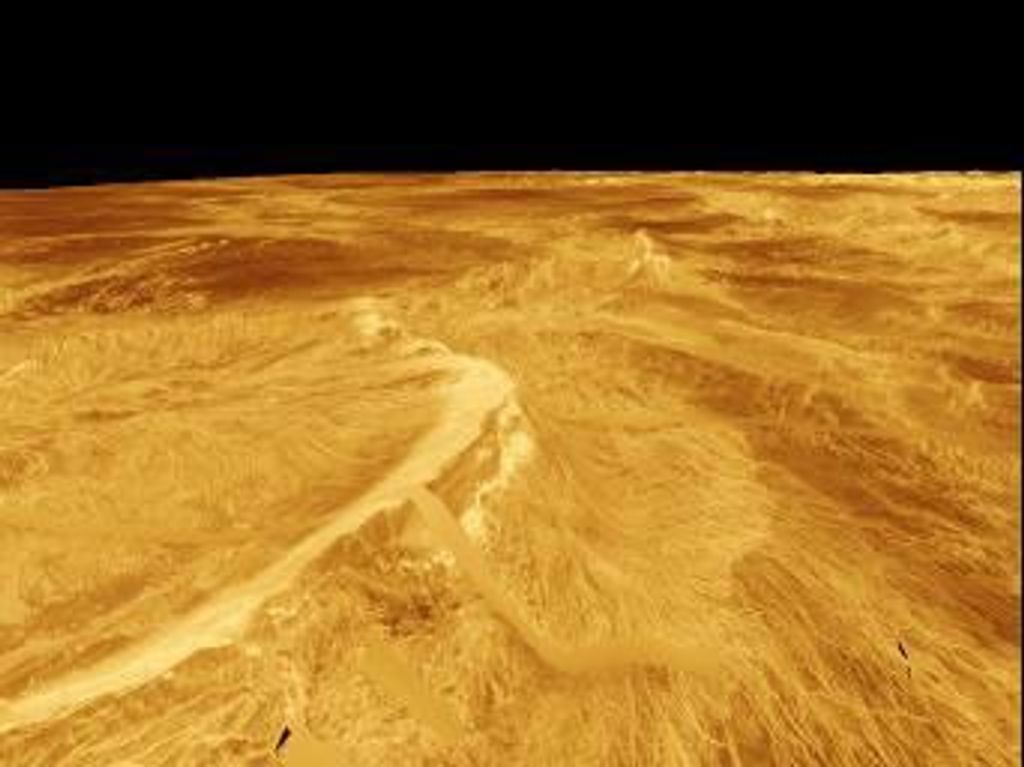

The source of potential trouble can be found inside Jupiter itself. Well below the Jovian cloud tops is a layer of hydrogen under such incredible pressure it acts as an electrical conductor. Scientists believe that the combination of this metallic hydrogen along with Jupiter’s fast rotation — one day on Jupiter is only 10 hours long — generates a powerful magnetic field that surrounds the planet with electrons, protons and ions traveling at nearly the speed of light. The endgame for any spacecraft that enters this doughnut-shaped field of high-energy particles is an encounter with the harshest radiation environment in the solar system.

“Over the life of the mission, Juno will be exposed to the equivalent of over 100 million dental X-rays,” said Rick Nybakken, Juno’s project manager from NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Pasadena, California. “But, we are ready. We designed an orbit around Jupiter that minimizes exposure to Jupiter’s harsh radiation environment. This orbit allows us to survive long enough to obtain the tantalizing science data that we have traveled so far to get.”

Juno’s orbit resembles a flattened oval. Its design is courtesy of the mission’s navigators, who came up with a trajectory that approaches Jupiter over its north pole and quickly drops to an altitude below the planet’s radiation belts as Juno races toward Jupiter’s south pole. Each close flyby of the planet is about one Earth day in duration. Then Juno’s orbit will carry the spacecraft below its south pole and away from Jupiter, well beyond the reach of harmful radiation.

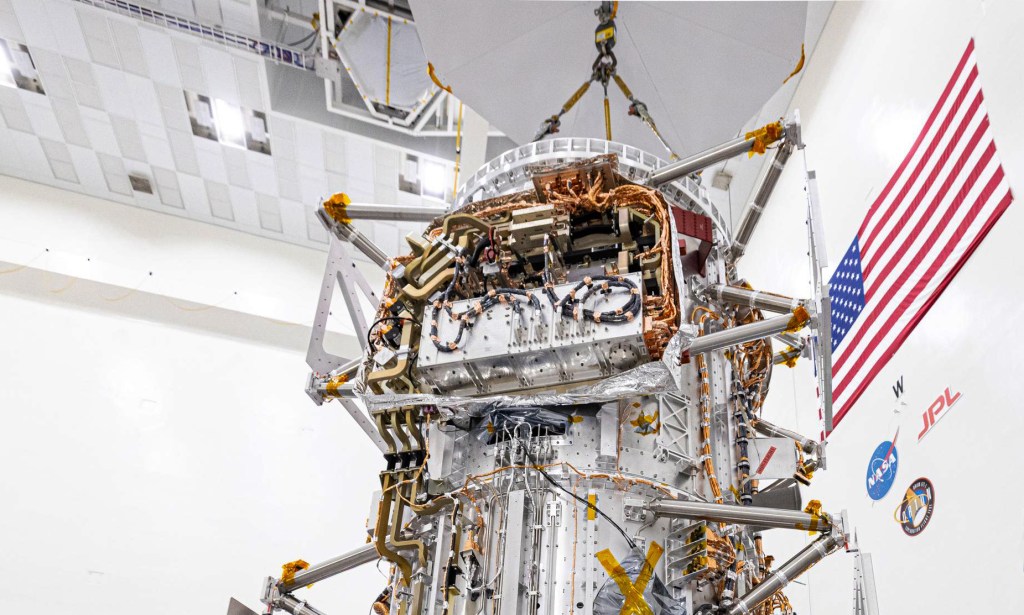

While Juno is replete with special radiation-hardened electrical wiring and shielding surrounding its myriad of sensors, the highest profile piece of armor Juno carries is a first-of-its-kind titanium vault, which contains the spacecraft’s flight computer and the electronic hearts of many of its science instruments. Weighing in at almost 400 pounds (172 kilograms), the vault will reduce the exposure to radiation by 800 times of that outside of its titanium walls.

Without the vault, Juno’s electronic brain would more than likely fry before the end of the very first flyby of the planet. But, while 400 pounds of titanium can do magical things, it can’t do it forever in an extreme radiation environment like that on Jupiter. The quantity and energy of the high-energy particles is just too much. However, Juno’s special orbit allows the radiation dose and the degradation to accumulate slowly, allowing Juno to do a remarkable amount of science for 20 months.

“Over the course of the mission, the highest energy electrons will penetrate the vault, creating a spray of secondary photons and particles,” said Heidi Becker, Juno’s Radiation Monitoring Investigation lead. “The constant bombardment will break the atomic bonds in Juno’s electronics.”

The Juno spacecraft launched Aug. 5, 2011 from Cape Canaveral, Florida. JPL manages the Juno mission for the principal investigator, Scott Bolton, of Southwest Research Institute in San Antonio. Juno is part of NASA’s New Frontiers Program, which is managed at NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama, for NASA’s Science Mission Directorate. Lockheed Martin Space Systems, Denver, built the spacecraft. The California Institute of Technology in Pasadena manages JPL for NASA.

More information on the Juno mission is available at:

The public can follow the mission on Facebook and Twitter at:

http://www.facebook.com/NASAJuno

Dwayne Brown / Laurie Cantillo

Headquarters, Washington

202-358-1726 / 202-358-1077

dwayne.c.brown@nasa.gov / laura.l.cantillo@nasa.gov

DC Agle

Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena, Calif.

818-393-9011

david.c.agle@jpl.nasa.gov