Bob Cabana: We looked down on Earth, not as citizens of any one country, but citizens of Planet Earth.

[ Eagle screeches ]

Launch Countdown Sequence: EGS Program Chief Engineer, verify no constraints to launch.

EGS Chief Engineer team has no constraints.

I copy that. You are clear to launch.

Five, four, three, two, one, and lift-off.

All clear.

Now passing through max q, maximum dynamic pressure.

Welcome to space.

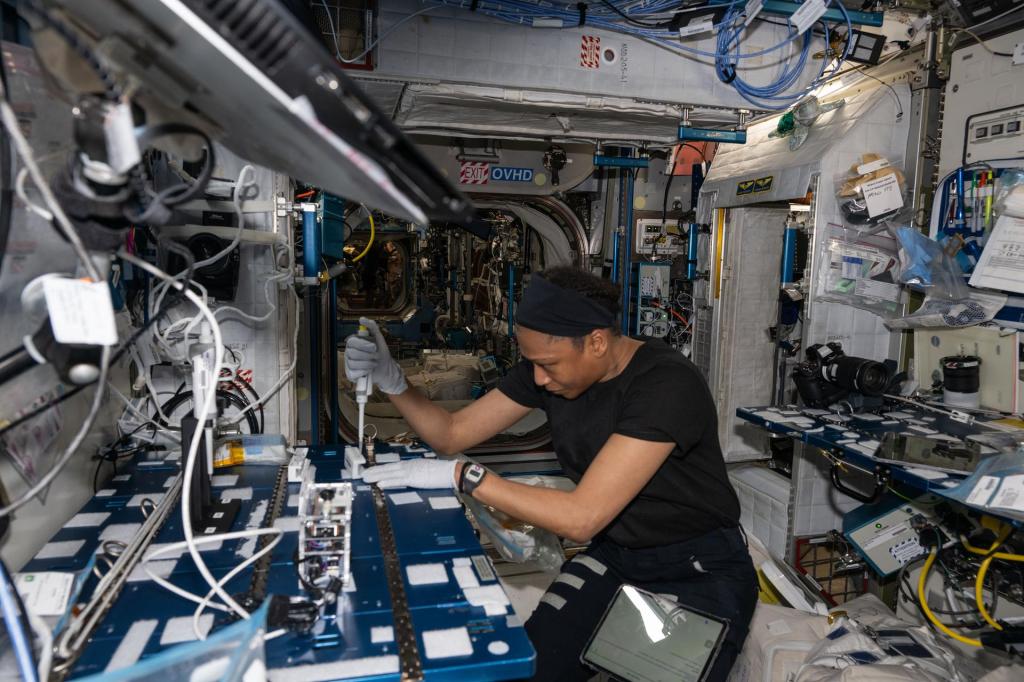

Joshua Santora (Host): Since the year 2000, there have been humans in space non-stop, every day. The International Space Station has been an engineering marvel, research laboratory, and platform for unparalleled exploration. This month, we celebrate the 20th anniversary of the launch of the first element of the International Space Station to lower earth orbit. In this episode, we sit down with the Space Shuttle commander who officially began construction of the ISS in space. Former astronaut Bob Cabana recounts his experiences in being the first American on station and turning on the lights.

All right, so I am in the booth this morning with Bob Cabana. Bob, thanks for being here this morning.

Bob Cabana: Absolutely, Josh. My pleasure.

Joshua Santora (Host): So, that’s the most simple introduction possible for you, but the longer introduction is — let me see if I can get this right — Naval Academy graduate, Colonel in the Marine Corps…

Bob Cabana: Yep.

Joshua Santora (Host):…astronaut, test pilot, Kennedy Space Center center director, and four-time Space Shuttle astronaut.

Bob Cabana: Yeah, that sums it up.

Joshua Santora (Host): We also have a biking enthusiast, as well as a recreational pilot, mud-runner, and I think the only things we’re missing are juggler and ballet in there.

Bob Cabana: I’m a lousy juggler. But I’m doing a 100-mile bike ride on Sunday. I’m gonna do the Space Coast Century.

Joshua Santora (Host): Oh, very good, very good. That’s awesome. But we have you here today to talk about the International Space Station. It is very arguably the greatest engineering accomplishment of humanity’s history, and you had the privilege of being there when we started the space station.

Bob Cabana: What a phenomenal accomplishment the space station is. Superb engineering test bed to prove the systems that we need or long-duration space flight and establishing a presence beyond our home planet and our solar system. Just a model of international and commercial partnership, you know, as we move forward. But, I mean, when you consider that we’ve got the United States, Russia, Canada, Japan, the European Space Agency and all its partners, and we’ve been working together as one up there for now 20 years, I mean, that is amazing.

In spite of all our political differences, the crews on the space station and the crews on the ground in Mission Control, we work together as one. And I think it’s a model for how we move forward as we return to the moon and we go on to Mars.

[ music ]

Joshua Santora (Host): I want to kind of take people back to, like you mentioned, 20 years ago. Can you give us a picture of what’s happening in the world and in the NASA world? Because obviously, like, this is a huge moment. It’s a pivotal moment in our history. So, set a scene for me here.

Bob Cabana: I’ll go back a little bit further. As we were doing the International Space Station, at the time, I’d gotten back off my third flight, my first command, and I was asked to be the chief of NASA’s Astronaut Office, and that was August 1994. And this is the time that we had just agreed to do the Shuttle-Mir Program with our Russian partners. And we would not have been successful on the International Space Station had we not first done Shuttle-Mir with the Russians. So, my first trip to Russia was in January of 1995, not long after the wall had come down.

And I went over to see how Norm Thagard and Bonnie Dunbar were doing. They were the two astronauts priming back-up training to fly that first Shuttle-Mir mission. And also to see what kind of accommodations were in Star City for Shannon Lucid, who was also going up on Mir. And to me, it was really kind of surreal. I remember it was 11:00, 12:00 at night, and I went cross-country skiing with Swedish astronaut Christer Fuglesang, who was over there training, and here I am, an active-duty Colonel in the United States Marine Corps, cross-country skiing with this Swede in the middle of the night on what was a secret base, going through holes in fences. It was just really unique.

Joshua Santora (Host): Wow.

Bob Cabana: But anyway, so, the Shuttle-Mir Program allowed us to work with the Russians to do the International Space Station. The docking adaptor that we put — STS-71 Atlantis was the first mission to dock with the Mir Space Station.

Mission Control: After 20 years, our spacecraft are docked in orbit again. Our new era of space exploration has begun.

Bob Cabana: And we had moved the airlock out of the middeck into the payload bay, and then we put the Russian docking adaptor on it. The systems that we actually docked with Mir, and it’s the same system that we docked with the International Space Station, was a Russian design, and it was based on essentially the same docking mechanism that was on the Apollo-Soyuz spacecraft.

So, you know, it was really interesting building that relationship, working with the Russians, and setting the stage for that first space station assembly mission. So, I’d been chief of the Astronaut Office for three years, and I really wanted to go fly in space again. And I got assigned to fly that first space station assembly mission.

Launch Control: From the Kennedy Space Center in Florida, this is Space Shuttle Endeavour launch control. This mission will mark the beginning of a five-year orbital assembly of the space station and kick off a new era of international space exploration using the resources and expertise of 16 nations.

Joshua Santora (Host): What’s that moment like? I mean, that’s got to feel, like, really special.

Bob Cabana: Well, it was just cool. I mean, it’s always cool to fly at first, but it was great to be back in the training flow for another mission. So, if I look back on, you know, that time while I was chief of the Astronaut Office, we established our relationship with the Russians. I developed a relationship with the Russians that I worked with in Star City. We had crews flying on the Mir Space Station. And I started assigning the crews for the future International Space Station missions and had assigned crews to the first three missions, essentially.

And folks didn’t necessarily want to be assigned to space station missions at that time because the program had been delayed. We were flying eight to nine shuttle missions a year, and you could fly a lot more frequently or fly a shuttle mission, you know. Committing to fly on a space station mission meant training in Russia. It meant learning Russian. It meant being assigned at least two years ahead of time to train to go fly on a space station.

Joshua Santora (Host): Wow.

Bob Cabana: It was very challenging. It was not something that was easy, and our method of training astronauts to fly in a space station and working with our international partners has changed over time. It’s still a two-year training flow for a specific flight, but I think we have a better understanding of what’s required and we have a better understanding how to work with our Russian partners in learning the Soyuz systems and the Russian systems on the space station and so on.

So, bottom line, it was a challenge for those folks on those first missions. Now, the assembly mission, that was run just like a standard NASA Space Shuttle mission. And we were assigned as a crew a year ahead of time. We ended up flying about a year late from when we were supposed to because of delays that were encountered. But I remember it was November of 1998. I had the entire crew over to my house, and we watched the FGB launch on a Proton rocket from the Baikonur Cosmodrome in Kazakhstan, and that was a successful launch, and we knew we had a mission.

Joshua Santora (Host): And the FGB was the Russian portion, the first piece?

Bob Cabana: The first segment. And that was actually — if you look at the designation of that, that was Assembly Mission 1 A/R — American/Russian.

And that’s because the FGB was built in Russia, but we paid for it through Boeing — on a contract with Boeing — and it was a US-paid-for module built by the Russians.

Joshua Santora (Host): Hm. Wow.

Bob Cabana: So, and the FGB — Functional Cargo Block — was named “Zarya”, which means “sunrise” in Russian. And once that launched, we knew we had a mission.

Joshua Santora (Host): Yeah.

Bob Cabana: And two weeks later, we were definitely going to space with Node 1, the Unity node. So, we were STS-88. That was a Space Shuttle designation. But from an ISS point of view, we were flight 2A — the second American assembly flight to ISS. But it was the first assembly mission. So, I had an awesome crew, you know. My pilot, Rick Sturckow, a Marine, that was his first flight. Rick is now one of the test pilots for Virgin Galactic, flying his rocket plane, you know.

Joshua Santora (Host): Oh, very cool. Oh, man.

Bob Cabana: And he went on to fly four Space Shuttle missions, commanding two of them. Jerry Ross was doing — he was lead for the EVAs, an EVA expert. Nancy Currie was my flight engineer and prime arm operator. Nancy has a PhD in industrial engineering and had been a helicopter pilot before coming to NASA. Jim Newman. Jim is an expert in rendezvous and proximity operations. He was on the crew and also one of my EVA members. And then we had Sergei Krikalev added to our crew.

Sergei had flown on the Space Shuttle back when Vladimir Titov also flew on a Space Shuttle mission and had trained in the United States as part of our exchanges. And he got added on to have Russian experience as we went up.

Bob Cabana from STS-88: Sergei has just been a real asset on this flight. I don’t think we’d have hardly any pictures or any time to do anything if we didn’t have him helping out. He’s super at helping us with EVA, and he’s super with just about everything.

Bob Cabana: And so that was the crew. And on December 4th, we launched on the Space Shuttle Endeavour off with the Node 1 tucked away in the payload bay to begin assembly of the International Space Station. And we tried to launch on December 3rd, but we were unable to. Things didn’t go right in the launch count. It just wasn’t real smooth.

Joshua Santora (Host): Sure.

Bob Cabana: And the weather wasn’t all that great. But we had an issue starting one of the auxiliary power units, and by the time figured out that everything was okay, we counted down to 18 seconds and didn’t go.

Joshua Santora (Host): Oh, man.

Woman: This is ST.

Launch Director: I copy.

[ Radio chatter ]

Is that an LCC hold for you Ray?

Man #1: Hold on.

Woman: I don’t know if we can explain it. We have an LCC violation.

Launch Director: All right, last time, the pick up is 858:0101.

Man #1: Copy. And we concur.

Launch Director: Heat com, everything looking okay on your side? They’re sitting right at 14-7.

Woman: That’s correct. Everything looks great.

Launch Director: Anybody else?…Look closer, folks.

You still a go?

Man #1: No, sir.

Man #2: On your mark.

Launch Director: NTD flight. We are no-go for launch.

Man #1: Copy that.

Launch Director: Yes, sir, we’ve picked up the count. We’re at 24 seconds. Request to cut off.

Man #1: Please cut off.

Man #2: Yes, sir.

Bob Cabana: And it was because of the time that it took to determine whether or not, you know, everything was okay to launch, and then they realized we didn’t have — we delayed enough that we didn’t have enough propellant in order to do the rendezvous. So, we scrubbed 18 seconds from launch.

Joshua Santora (Host): Oh.

Launch Director: Close call there, Ed. Good job.

Ed: Yeah, it was a close call.

Bob Cabana: And it was okay, you know,

Joshua Santora (Host): Sure.

Bob Cabana: We went back, and then the next night, we went out, and it was absolutely perfect. It was one of the smoothest launch counts I’ve seen.

Launch Commentator: Everything continues to look good, and we are cleared for launch today. No problems are being reported from the vehicle or the crew.

Bob Cabana from STS-88:Hello Bruce, let’s go do this tonight.

Bruce: Amen. We’re gonna do it tonight. You have a very exciting mission ahead of you, and we wish you maximum success.

Bob Cabana from STS-88:Endeavour Roger, thanks a lot.

Launch Commentator: Ten, nine, eight.

We have a go for main engine start.

We have main engine start.

Four, three, two, one.

We have booster ignition and liftoff of the Space Shuttle Endeavour with the first American element of the International Space Station uniting our efforts in space to achieve our common goals.

Bob Cabana: My daughter and I are real “Wizard of Oz” aficionados.

Joshua Santora (Host): Okay.

Bob Cabana: And they had re-released the “Wizard of Oz” all color-corrected and up to date and everything right before my launch.

Joshua Santora (Host): Right.

Bob Cabana: And so my daughter and I went to see it, and it was awesome. So, the night we didn’t launch, the next day, there was a picture on the front page of the Orlando Sentinel. And it had Endeavour on the launch pad with this huge rainbow, and Red Huber took the picture.

I have it framed in my office, and Red signed it for me. And like I said, everything went perfect, and the first wake-up music that we had on orbit the day after launch was Judy Garland singing “Somewhere Over the Rainbow.”

Joshua Santora (Host): Awesome.

Judy Garland: Somewhere over the rainbow, way up high.

Bob Cabana: I mean, I had tears coming down. It was emotional.

Joshua Santora (Host): Yeah.

Bob Cabana: And, you know, it just — it all came together. And so what I tell folks is that somewhere over the rainbow, dreams really do come true because we launched over that rainbow, and we had an absolutely dream flight from start to finish, Josh.

Judy Garland: There’s a dream that you dare to dream. Dreams really do come true.

Mission Control:Endeavour Houston, good morning, and that long distance dedication was to Bob from Sarah.

Joshua Santora (Host): Great. So, getting into kind of this mission, obviously, like, there was a design for the space station, there was a plan for the space station, but did you really kind of grasp the magnitude of what you all were beginning?

Bob Cabana: Oh, absolutely.

Joshua Santora (Host): ‘Cause the implications have been tremendous.

Bob Cabana: I think so, and we knew the criticality of being successful on that very first flight. I mean, we trained really hard. It was — You know, one of the things that we talked about in building the International Space Station — it was called the wall of EVA, all the space walks that we had to do in order to be successful building this space station.

We had three of them on my flight. And, you know, what we showed was we know how to do this, and we were extremely successful. I can’t think of how it could’ve gone better from start to finish. When you talk about the impact, did we know what we were doing, I wish I’d have brought it with me. I can’t remember it verbatim. But when we were inside the space station for the first time — and I’ll come back to more of that — but we made the first log entry in the log book of the International Space Station, and I wrote — I was sitting there thinking about what I wanted to say, and I wrote it all down, and then the entire crew signed it.

Joshua Santora (Host): Cool.

Bob Cabana: But the bottom line was that we recognized the importance of what we were doing. And the one line that I remember distinctly was “From small beginnings, great things come.”

Joshua Santora (Host): Awesome.

Bob Cabana: And when I look back on that small beginning on the International Space Station, just those two modules, a Unity mode — and what an appropriate name, Unity binding us all together as one — and Zarya, sunrise, a new beginning, the size of the International Space Station then and what it is today and all that we have accomplished and learned on it and have yet to learn on it and what it is still capable of doing. You know, it truly is just a phenomenal facility.

Joshua Santora (Host): So, you mentioned this log book. So, is this a document that every commander that goes up writes in?

Bob Cabana: Yeah, and the crew — absolutely. It’s up on orbit right now. It’s the International Space Station log book. And hopefully on the last flight of the space station, somebody’s gonna bring it home.

Joshua Santora (Host): Yeah. So, is it just, like –

Bob Cabana: It’s like the ship’s log, you know. “Captain Kirk, stardate.”

Joshua Santora (Host): So, is it light-hearted? Is it very professional? Obviously yours was a very, like, important milestone of, like, “We’re doing this for the future”.

Bob Cabana: It’s a takeoff on ship’s logs.

Joshua Santora (Host): Okay.

Bob Cabana: And there are special entries that get made. I mean, on New Year’s Eve, there’s always a special entry that the officer of the deck has to put in the ship’s log — on special occasions and stuff like that.

So, it’s a document that crews have signed, that crews have made special entries in. It’s not so much an exact “This is everything that’s gone on on the space station,” but it kind of takes after, you know, the history of log books on ships.

Joshua Santora (Host): So, kind of take us through this moment. Obviously, like, you have a mission on orbit. You’re preparing your — You’ve captured the Russian portion. You’re getting ready. Kind of talk us through — like, what’s this like to finally, like, join these two and then allow it to become one, essentially?

Bob Cabana: Well, you know, first off, watching Nancy lift the node out of the payload bay, she had an inch or less of clearance on each side, and she just — I didn’t know you could move the arm that slow. But, I mean, she did it so precisely.

Bob Cabana from STS-88: Had him take a shot where the camera was moving because Nancy was moving it so slow that it looked like a still photo every time I tried to take something.

Bob Cabana: And then we lifted it up — She lifted it up and positioned it over the docking station, and I fired the thrusters to bring the two pieces together. And then we used the docking system to drive them close and close the latches, and that mated Unity to the Orbiter. Then, we did the rendezvous with the FGB. And it was a flawless rendezvous.

And we have all kinds of tools during the rendezvous — the Ku band antenna on the Orbiter provides range and range rate. We had handheld lasers when we got in closer, shooting it to get range and range rate.

The Orbiter, the computers on it, even after we upgraded, only had 256k of memory in each one, so you’re limited as to the — They’re very radiation-hardened computers, very reliable, and run extremely well, but we had to load software depending on which phase of the mission we were in because it wasn’t all in the computer’s capability.

So, what we used to do to get more information available to us is we’d bring IBM 760 laptop — 760XD computers onboard — and we set up our own local area network pulling data off the PCMMU from the Orbiter.

And one of the programs that we ran was called RPOP — Rendezvous Proximity Operations Program. And Jim Newman, prior to being selected as an astronaut, used to train Rendezvous Proximity Operations. He was one of our trainers. And he actually wrote the programs for RPOP. So, I had that running, and that, it shows your rendezvous profile.

It predicts where you’re gonna go so you kind of know based on the jet firings, you know, how you’re falling. And, of course, you’ve got guidance from the Orbiter itself. And then I got Jim Newman, who has trained people on all of this, you know, in my ear, “What do you think about a couple of ops? How about an in?” You know, so…

Joshua Santora (Host): Just suggestions, ’cause obviously you’re in charge at this point.

Bob Cabana: I’m in charge. So, I’m using my onboard internal Coleman filter to filter all this data that I have to do what I think is right for the rendezvous. And it went perfect. So, I flew the FGB right down into the payload bay, and I couldn’t see out the windows because the Node was in the way. After a certain point, I’m bringing it into the payload bay just relying on cameras.

I had a center-line camera looking up at it and one on the end of the arm looking across at it. And flew it down so it was stopped perfectly stable. The grapple fixture was three feet from the end of the arm. All Nancy Currie had to do was move that arm three feet and grab it, right?

But we had to wait until we were over a Russian ground site to confirm that the FGB was in free drift before we grabbed it. ‘Cause you wouldn’t want to grab ahold of it and have its flight control system still on, fighting the arm, right?

Joshua Santora (Host): Sure.

Bob Cabana: And breaking the arm.

Bob Cabana from STS-88: Got drift? We were wondering — we seem to be moving pretty good here — what the first ground site was over Russia where we could verify…and make sure everything’s good.

Mission Control: Bob, good question. Sally says we’re verifying it as we speak.

Bob Cabana: So, it’s all stable, it’s right there, and we’re waiting to grab it. The orbiter — It’s hard to fly six degrees of Frenet at once.

Pitch, roll, and yaw as well as the translations, you know, X, Y, and Z. So, we programmed the auto-pilot to maintain the attitude, pitch, roll, and yaw, and then all you have to worry about are the translations.

Joshua Santora (Host): Sure.

Bob Cabana: So, it drifts slightly, and there’s a deadband that it operates within, and when it reaches the edge of that deadband, the jets fire to center it back up again. When the jets fire, you don’t always get a pure pitch, roll, and yaw. You get a roll-yaw coupling.

Joshua Santora (Host): Sure.

Bob Cabana: Inertial coupling.

Joshua Santora (Host): Obviously, like, it’s not like you’re flying through the air. It’s a very different game.

Bob Cabana: Yeah, but — similar but different. So, what happens when you get this inertial coupling is instead of getting a pure pitch, roll, or yaw, you get a translation, also. And we hit a deadband, and this happened. All right, well, everything was stable, and we were just waiting to grab it. And so all of a sudden, this 45,000-pound mass FGB is moving into the payload bay and toward the arm. It’s gonna hit us.

And so I fired the jets to back away from it, and nothing happened. It’s still coming to hit us. And you program the digital auto-pilot depending on the phase of the mission, and we were in a very fine control. There’s an A digital auto-pilot and a B that you’ve programmed, and I was in the B DAP for very fine control.

Fortunately, I had enough sense to select the A DAP, get some more control power. And we were able to back away from it. And, you know, then that saved us there, and move back in, got all stable again, and we’re ready to grab it once it was in free drift.

So, while all this was happening, you know, Jim, who had been very vocal throughout the entire rendezvous offering advice — it was just dead silence in the cockpit, right? Nobody said anything.

Joshua Santora (Host): So, I’m assuming everybody’s seeing this happen in real time.

Bob Cabana: Oh, yeah, yeah.

Joshua Santora (Host): So everyone knows what’s going on.

Bob Cabana: When it was all over, I said, “Jim,” I said, “…how come you didn’t offer me any advice when that happened?” He said, “Ohh, I know when to keep my mouth shut.” But that, you know, that was probably — For me, that was the most challenging part of the whole mission, you know, being able to react to that and do the right thing.

But once it was all stable again, we got over a Russian ground site, they said, “You’re clear to grapple.” Nancy grabbed it, we lifted it up, positioned it over the top of the Node on the other pressurized mating adaptor — PMA2. And this was a blind — We didn’t have anything where we could see precisely how we were aligned.

We had a visual system that had dots that was supposed to help us, and we had camera views and stuff that we’d practiced a lot in the simulator, which is not always as exact as actually being in real life.

Joshua Santora (Host): Sure.

Bob Cabana: We were able to position it, make sure it was in the right spot, fired the thrusters again, brought those two pieces together, and drove it tight. And at that point, we had the beginnings of the International Space Station.

[ music ]

Jim and Jerry went out subsequently on a couple of space walks connecting power and data connectors on the ISS, and then it came time for ingress. Prior to ingressing, Sergei and I activated the space station.

We had another set of 760XD computers back on the aft flight deck where we sent the commands to power up and activate the International Space Station and get its systems working. And we’d spent hours in the software development facility in Houston — Boeing, out at Sonny Carter — testing the software. We found errors that were corrected.

We did mission-essential integration tests at KSC. We spent hours down here at the Cape testing the Node software, hooked up to an emulator FGB, where we found more problems and corrected them. And when we got on orbit and sent those commands, I’m telling you, nobody was more surprised than me that everything worked perfect.

Not one anomaly. I mean, it just — every procedure that we went through — We powered it up, and everything worked perfectly.

Bob Cabana from STS-88:But this is our goal — it’s building a space station and setting the pace for the future. We’re sure enjoying it up here.

It’s extremely challenging, but it’s also extremely rewarding. And when you get to look out the window and Zarya and Unity joined together and knowing that you get to go inside tomorrow, it’s pretty awesome.

Bob Cabana: And that set the stage for ingress into the FGB, which was on December 10, 1998. And when it came time to enter the space station for the first time, I’d gotten a lot of questions from the media — who’s gonna be the first one inside?

And I didn’t tell anybody. I didn’t even tell the crew. And when it came time to open the hatch, I said, “Sergei, get up here.”

Mission Control: Cabana and Sergei Krikalev enter the module.

Joshua Santora (Host): Yeah, and there’s video of this out there. So, I mean, you can see literally, like, you’re there at the passageway between these two modules…

Mission Control: Commander Bob Cabana and Sergei Krikalev entering the module together. The first astronauts aboard the International Space Station in orbit.

Joshua Santora (Host):…and you grab Sergei, and walk us through what happens.

Bob Cabana: So, I believe that this is an international space station. We need to enter as an international crew. So, every hatch we opened as we went from the airlock through the docking station into the pressurized mating adaptor into the Node, into PMA2, into the FGB, Sergei and I enter each one side-by-side.

So, there was no first person in the International Space Station. I got to be the first American, and Sergei was the first Russian.

But I thought that really important that we make that statement, that we enter as a international crew. And then when we’d finally ingressed through all the modules and we were into the FGB, we set up and we did a press conference from inside the FGB — the first press conference from the International Space Station with the entire crew.

Bob Cabana from STS-88: It’s unbelievable. If you’ve got live coverage, look at the volume Sergei is floating around in. We are so pleased and excited and proud to be a part of the team that made this happen. And our special thanks to all the hours, all the hard work.

We remember when Unity was just an aluminum shell, and it is a truly fine piece of hardware. And just thanks to everybody in the Space Station program for all their hard work.

Bob Cabana: And, man, we had a lot of work to do to get it ready. And Sergei, in addition to being on that flight, was also on the first crew to actually live on the International Space Station. The first crew that launched the space station — that was in October of 2000. And Commander of the Soyuz was Yuri Gidzenko, and the commander of the space station was Bill Shepherd.

And Sergei was the engineer on that flight. And we wanted to make sure that we got as much done to have it ready for when the crew arrived so that they wouldn’t have as much work to do. So, we did everything that we had to do — and most of what we were doing was removing launch constraint bolts.

There were extra bolts and panels put in to make it strong enough to survive the launch, but were not required once it was on orbit, and they had to come out. So, we were moving all the launch restraint bolts and panels. We went into the FGB, and we cleaned all the filters. We opened up. You know, once the system started running and the fans were running to scrub the air and everything, any debris that didn’t get caught on the ground was now on all the filters, so we cleaned all the filters in the modules and just continued to get stuff set up and ready for the crew.

That night — I had a rule that — I had a couple crew members that really needed eight hours of sleep. So, on the middeck of the Orbiter, my rule was we’re gonna darken ship on the middeck when it’s sleep time, and you can stay up. You don’t have to go to bed if you don’t want to. You can sit up on the flight deck, look out the window, you know, send e-mails home, whatever, but you got to be quiet. And Jim Newman stayed up late. He was up on the flight deck. And this was when, you know, the crew had gone to bed. We’re docked to the space station. The hatch is open and everything. And we slept on the Orbiter. And he wants to go look in the space station one more time before he goes to sleep. So, he goes down on the middeck, and he’s being really quiet, you know, and where I was sleeping and Nancy Currie was sleeping, it was where the airlock used to be, and we had these big bags in there.

We called them refrigerator bags, but it had all the stuff that we were taking up to space for the space station, leaving stuff on it and everything. And I was snuggled between two of them and she between two others, and he went between them in the middle, and he doesn’t want to wake me, you know. And he goes into the airlock, turns the corner, and goes up into the space station, and who does he find but me and Sergei Krikalev in the space station.

Joshua Santora (Host): Hard to leave?

Bob Cabana: It was. So, we were just doing work. We were just doing more — and we were just talking about “What does this mean? What is the future of what we have done here?” And he joined us. And if you were on a — We set up sleep shifts on the Orbiter, so it was like eight hours of sleep. So, think of it as I’m going to bed at 11:00 at night, and I’m getting up at 7:00 in the morning, all right? That’s my eight hours of sleep.

And I think it was finally about 4:00 in the morning, and I turned to Jim and Sergei and I said, “That’s it, you know. We’re done. We got to get some sleep. We got a really busy day tomorrow. We’re gonna close things up, you know, and get ready for another EVA”.

And so I made the three of us go to sleep. But that was a special night. I mean, it was just — Just to be in the space station, spending all that time in there, making the log book entry, talking about what the future of this was, what it meant to be working together to lay the groundwork to establish a presence.

And, you know, I look back now, and anybody that is 18 years old or younger in the world has never known a time that there weren’t humans in space. Since October 2000, we’ve had a permanent crew on the International Space Station, and that’s our destiny, is to establish that presence, to learn, to explore, to go beyond our home planet.

Now, I just, you know — It was pretty special.

Bob Cabana from STS-88: Words can’t express it. It’s unbelievable to be part of such a great program bringing all these counties together, working together in space for everybody’s betterment, and just, you know, it’s really outstanding hardware. It’s just so nice inside. It’s really nice to be in a new home.

[ music ]

Joshua Santora (Host): We’re celebrating 20 years of the International Space Station. So, looking ahead, more years of the space station, more years of NASA, what do the next 20 to 60 years look like for us? What’s the future?

Bob Cabana: I look back on — Our first 60 years were pretty darn amazing.

Joshua Santora (Host): Yeah.

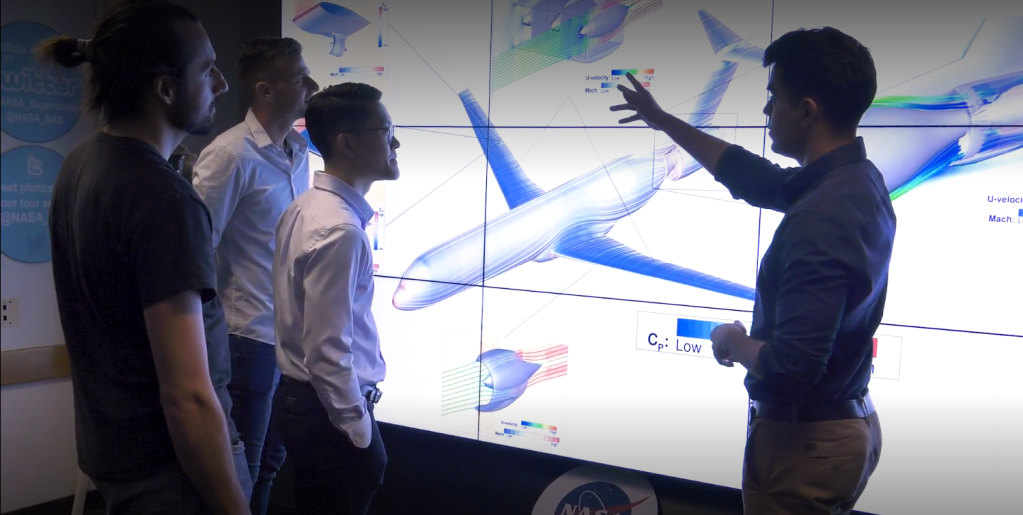

Bob Cabana: Right? And we have accomplished so much. But our next 60 years are gonna be better. You know, as amazing as the first 60 were, the next 60 are gonna be phenomenal. I mean, look at the changes just here at the Kennedy Space Center, how our multi-years of space board has grown and come to be.

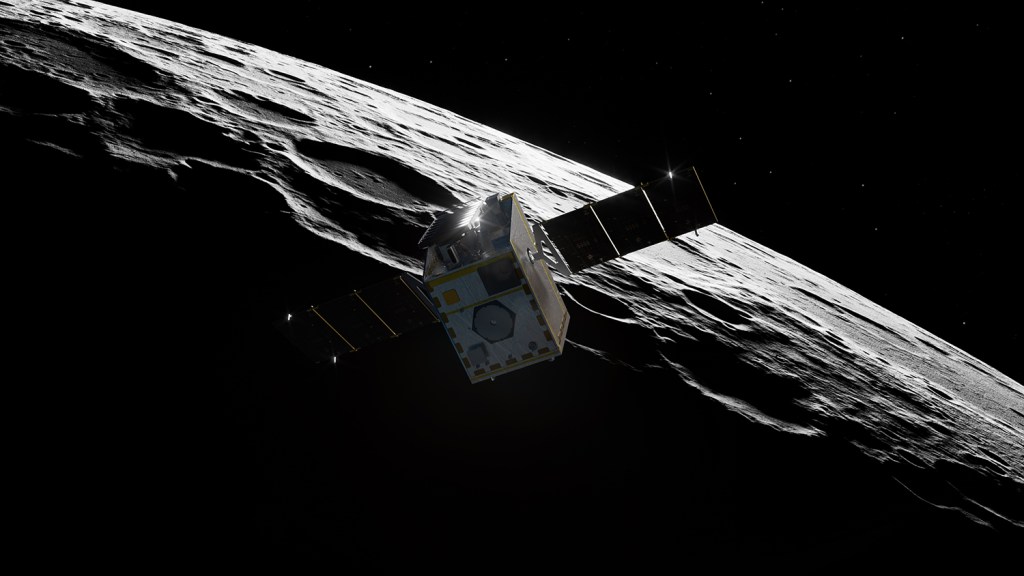

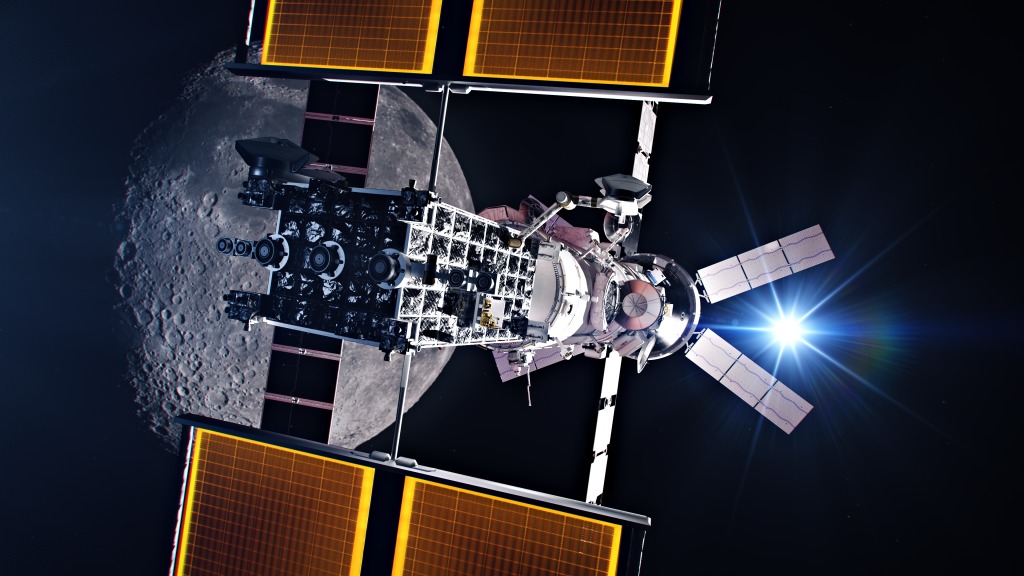

You know, and it’s only gonna continue to grow. The gateway, the platform we’re gonna put in orbit around the moon, it allows access to anywhere on the lunar surface. It’ll be an international partnership. It’s gonna be a commercial partnership. You know, people talk about commercial space and government space and new space and old space, and there’s only one space, you know? And if we as a nation are gonna be successful, we need them all integrated together as one. And I just look forward to how we are working together and what we are accomplishing.

And it’s gonna be phenomenal. And then going on to Mars. I think we have an absolutely outstanding future in front of us, and we just need to continue to apply ourselves, and great things are gonna come. It’s gonna be better. The next 60 are gonna be far better than the first. You often wonder, “Was I born too soon or too late?

Man, if I’d have been born sooner, maybe I could’ve gone to the moon” or “Man, if I were born later, maybe I could go to Mars.” But the bottom line is, we were all born for the right time for us in this life that we live, and I can’t imagine not being here at the Kennedy Space Center right now, being part of this amazing team that is making history.

And we’re gonna look back years from now and say, “Wow, wasn’t that an amazing time? Look what we put in place. Look what we made happen and where we are now”. And that, to me, it’s one of the most rewarding things ever.

Joshua Santora (Host): I don’t want to overlook the fact that you are the Kennedy Space Center director. You are now actually the second longest-serving center director.

Bob Cabana: I got a couple more years to go, and I’ll be up there with Dr. Debus, but yeah, it’s been a while. It’s rewarding to me to see what we’ve accomplished. I got asked the other day, “Hey, what motivates you, Bob?” I challenged somebody that was in first, I said, “Well, what motivates you?” They were working on a project, and I was trying to get them to use what motivates them to be able to use for part of this project and build on it.

And they asked me the next day out of curiosity, “Well, what motivates you?” And I said, “What motivates me is being privileged to lead this awesome KSC team, to be able to walk into a space and see the smile on someone’s face when you ask them what they’re doing and they explain it to you and they share the joy and the work that they have.” That motivates me, you know.

It’s the success that we have had in our transition from shuttle to establish ourselves as this multi-user space port today. That success motivates me to want to do better and to even do more. You know, I’m motivated just driving over the Indian River Lagoon in the morning, seeing the sun come up over the Atlantic Ocean and being part of this amazing team at this beautiful wildlife preserve that’s the Kennedy Space Center.

Joshua Santora (Host): Very good. Thinking about the coming year, if you had to pick the one thing you’re looking forward to the most –

Bob Cabana: Commercial crew. No doubt. This is number-one priority. You know, everybody gets disappointed when they’re not the number-one priority. ‘Cause everybody feels they’re number-one. And programs feel slighted when you don’t mention them, but the bottom line is, it’s crucial to us to get a crew flying to the International Space Station on a US rocket from US soil. And I want to see that happen.

And we’ve got — right now, we’re on track, you know. It can change. We’re not gonna fly till we’re ready to fly, but SpaceX is looking at an un-crewed demo flight in January with a crewed flight in June of next year, and Boeing is looking at an un-crewed flight in April with a crewed flight in August.

I got asked, “Well, is there more pressure now that the Soyuz had the anomaly and the crew had to abort?” And the answer is no. The pressure was always on the commercial crew team. We can’t work any harder or faster than we’re already working, and we are not gonna do anything that is unsafe. We have procedures that we need to follow.

We have criteria that need to be met, and we’re are gonna ensure that as we work through the processes, that we meet those criteria, that we can certify this vehicle, and that when we fly, it’s gonna be safe to fly and we understand the risk that we’re taking.

It will never be without risk. We are in a risky business. But we need to understand what the risk is, mitigate is as best as possible, and make sure that we’re not taking undue risk. And I will feel a lot more comfortable on both of these vehicles when we have shown that we have a proven abort capability. And as the Soyuz has shown, you know, capsules are very robust in an abort situation, much more so than a winged vehicle.

And I just want to make sure that, you know, if we don’t always have mission success, we ensure that we take care of the crew. I don’t want ever want to have to have another Challenger or Columbia.

Joshua Santora (Host): Yeah, and you mentioned that Soyuz mission, seeing the two crew members back on Earth, hugging family. That’s a priceless moment, when you’re like, “Man, this didn’t go like we planned, but everybody’s home”.

Bob Cabana: Amen.

Joshua Santora (Host): So, thinking about just the nature of this international partnership, I think something that people — if they’re aware of — have no clue the full magnitude of how much we cooperate, especially when we’re in space like that. And I think that especially now with kind of the way things are politically in the world, there’s lots of tumultuous things, obviously. Just recently, we had an issue with the Soyuz launch where we had an American and a Russian on board. Both safe, but certainly, like, this very amazing bond that holds us together that really, from my perspective, there is no division when we’re in space. Can you speak to — Is that the reality? How does that happen? Like, how do you leave Earth and, like, everything becomes better?

Bob Cabana: Because we have a common goal, and we depend on one another for our health and welfare. We’re in a very harsh environment where everybody has to work together as a team to be successful. And you can’t have division. You have to have a common purpose. You have to perform as a team. And, you know, more astronauts than I have said it — when you look down on the Earth from 200 miles high, there are very few boundaries that you see.

What you see is this beautiful blue jewel of a planet with its amazing continents and colors and thin little hazy line that’s our atmosphere over the top of it. That’s all that’s protecting us from that harsh void of space with its ultraviolet radiation and extreme temperatures and hostility, if you will. And space is the darkest, blackest void you can possibly imagine. No black on Earth does it justice when you’re on the sunlit side of the Earth.

And so I think, you know, we look down on Earth and we see ourselves as humanity, not as citizens of any one country, but citizens of Planet Earth. And so we work together. We have a common goal, a common purpose, and it’s larger than anything on Earth. As a pilot in the Marine Corps and as an astronaut, I’ve had the privilege of traveling all over the world and seeing a lot of different cultures and places and talking to a lot of different people, and we all want the same things, Josh.

We want good things for our children, we want to provide for our families, we want health and happiness, and you know, I think in many ways, many, many ways, we are more alike than we are different. And what we need to focus on more is our alikeness and not our differences.

Joshua Santora (Host): Well, Bob, from your military service to then your service here with NASA for a very long time — Bob, thanks for being here today.

Bob Cabana: Absolutely my pleasure, Josh. Thanks for having me on the show.

Joshua Santora (Host): As Bob mentioned at the top of the show, from small beginnings, great things come. I’m Joshua Santora, and that’s our show. Thanks for stopping by the Rocket Ranch. And special thanks to our guest — Marine, pilot, astronaut, and center director Bob Cabana.

To learn more about the International Space Station, go to nasa.gov/ISS. And please check out our other NASA podcast to learn more about what’s happening at all of our NASA centers at nasa.gov/podcasts. A special shout-out to my colleagues — our producer, John Sackman, sound man, Lorne Mathre, editor, Michelle Stone, and our production manager, Amanda Griffin.

And remember — on the Rocket Ranch, even the sky isn’t the limit.

[ Eagle screeches ]