TRT: 43:53

Sam Dove:When they call us to go do something, that’s what we do.

Launch Countdown Sequence: EGS Program Chief Engineer, verify no constraints to launch. EGS Chief Engineer team has no constraints.

I copy that. You are clear to launch.

Five, four, three, two, one, and lift-off.

All clear. Now passing through max q, maximum dynamic pressure.

Welcome to space.

Joshua Santora (Host): Welcome to the Rocket Ranch. I’m your host, Joshua Santora. When people think of the Kennedy Space Center, rockets are what likely come to mind. But we have more than rocket scientists here on the Space Coast. We’re a bit like a small city. In this episode, we meet a few Ranch hands with odd jobs you may not expect to find around these parts. First up, we talk with a marine biologist who actually gets to fish as part of his day job.

Dr. Eric Reyier: Literally, the best habitat we have here on center and probably just about the best habitat here in the county is, no joke, a stone’s throw outside those launchpads.

Joshua Santora (Host): Next, we sit down with a driver whose vehicle of choice weighs 6 million pounds and clocks in at a staggering one mile an hour.

Sam Dove: It has the power, the electrical power to do 2 miles an hour, but you never would do that, right?

[ Laughs ]

Joshua Santora (Host): Finally, a helicopter pilot who tracks animals and trespassers rounds out our glimpse into odd jobs here at the Ranch.

Dave Ramsey: We’ll be up in the air during launches looking for anyone trying to do damage to the rocket or just make themselves famous.

Joshua Santora (Host): Kennedy Space Center not only launches rockets, but it also doubles as a wildlife refuge. Looking after many of the critters here on the ranch is marine biologist Dr. Eric Reyier. I’m in the booth now with Dr. Eric Reyier. I will call him the fish doctor.

[ Both chuckle ]

Joshua Santora (Host): Dr. Reyier, thanks for being here.

Dr. Eric Reyier: Sure. Yeah, it’s my first podcast.

[ Laughs ]

Joshua Santora (Host): So, tell me a little bit about yourself. What’s your background? And obviously give some context as to why I would refer to you as the doctor of fishing.

Dr. Eric Reyier: Sure. So I’m a fisheries biologist here at Kennedy Space Center. I’ve been here now almost 20 years. I was planning on being here for two, but the place sort of grabbed ahold of me, and it’s hard to leave a job this interesting. I’m part of the Kennedy Space Center Ecological Program. It’s a group of, I think, about 15 biologists that work on a variety of environmental issues around the Space center, and so I’m a fisheries biologist here, but we’ve got marine-mammal folks, we got folks that study endangered species like scrub jays and sea turtles and beach mice, and we cross-collaborate on a number of issues around the space center, but, yeah, I came down, actually, from outside of Seattle to go to F.I.T. down there in Melbourne for a couple years, and it’s pretty spectacular. In fact, one of the first jobs I ever had coming here wasn’t related to fisheries, but when the shuttle would launch, we’d actually — right before a launch, we’d go into the pad perimeter — you know, the space shuttle was on the pad. It’s getting ready to go. A few days before launch, we’d go in, and we’d have to clear out all the baby alligators that had made it under the fence, and baby alligators are really fast. So there’s these ponds that collect deluge water from the shuttle, and these little baby gators could make it under or through the fence, and some turtles, too, and we’d have to hop in there, and we’d go in with just an empty truck, and we’d come out with a truckful of baby alligators and turtles, and we do that before every launch.

Joshua Santora (Host): Can you tell me a little bit about what’s going on as far as right around a launchpad, for instance? Because I know that that’s probably — when we think about if we’re harming the environment, people would expect it to be there. So what’s the environment like in that area?

Dr. Eric Reyier: Yeah, it’s just the opposite. That’s an excellent question. We think of rocket launches as really dangerous and very industrial, and, clearly, they are, but the impact of those launches is — the footprint is very small, and from our observations over the years, literally, the best habitat we have here on center — and probably just about the best habitat here in the county is, no joke, a stone’s throw outside those launch pads, and we’ve got huge sport fish that come, really, within the shadow of some of our launch facilities, and it’s because there’s no other development, but wildlife benefits tremendously from the space program, as well, so…

Joshua Santora (Host): Yeah, that’s awesome. So I want to step back for a second because, obviously, you just mentioned a lot of biologists and a lot of interesting wildlife that people may not be familiar with, so we need to paint a picture for what the Kennedy Space Center is, ’cause people say, “space center,” and they think rockets, they think smoke and fire, they think, obviously, like big production, but we’re surrounded by a wildlife refuge. Can you tell us more about what would people see if they came out here?

Dr. Eric Reyier: Yeah, they’d see a lot of green, to be honest with you. You know, I think it was back in the early ’60s — I think ’62. NASA needs a lot of space to launch rockets, both for public safety and security purposes. So early ’60s, they bought up a lot of property here, and they realized early on that most of it wasn’t directly gonna be used for rocket launches. The space center’s actually huge. You know, it’s about 140,000 acres of which, when you do the math, I think about 5 percent is actually used for space-launch infrastructure – launch pads, roads, buildings, et cetera. They, fairly quickly, ceded a lot of the natural-lands management to U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, who created Merritt Island National Wildlife Refuge, and then a little bit later on, the northern part of the property was actually — management was ceded to Canaveral National Seashore, as well. So we actually have a wildlife refuge and a national seashore that overlay Kennedy Space Center. Another interesting aspect of it is, NASA wants a security perimeter around their launch infrastructure, which makes sense. So early on, they establish this perimeter, which there’s no public access around these launch pads, and while the purpose was public safety and security, they sort of, coincidentally, created what we call a de facto marine reserve, and marine reserves, they’re being used more and more for marine management, where, basically, you set areas off-limits and let the ecosystem sort of persist in its natural state, and some areas are controversial. At the space center, they’re not, because it wasn’t really designed as a marine reserve. It was designed for security. Fish don’t know that, so the fish here have been, basically, unmolested now since 1962, and there’s been several studies that have shown that water within the security zone of Kennedy Space Center, they harbor higher densities of sport fish. Those sport fish are generally larger, and we have higher, overall, fisheries diversity within the space center than adjacent public areas that have been developed over the past few decades, and so it’s basically a gem here in east Florida. The fisheries habitat here is the best we have, really, on the east coast of the United States anymore. On the fisheries side, we’ve got red drum, black drum, spotted seatrout, tarpon, snook — all these really important sport fish, and a large percentage of the rest of that is actually managed in a fairly natural state. So you got a tremendous amount of habitat and wildlife issues that you have to attend to. The lagoon has a very high density of West Indian manatees, green and loggerhead sea turtles that use the lagoon as, basically, a nursery, as well. Bull sharks is the common fish in the lagoon. Our folks traditionally work on scrub jays, bald eagles, gopher tortoises, invasive hogs — most dense population of alligators left in any of the lagoons here at KSC. Much of the space center is actually co-managed either as Merritt Island National Wildlife Refuge or Canaveral National Seashore, and so NASA, as a federal agency, has to — they’re held to sort of a high standard on how they maintain their land and the wildlife and habitat land, and that’s sort of where we come in.

Joshua Santora (Host): Cool. And so what is your day job? Like, what do you do on a daily basis? Would we find you in an office? Are you outside, like, hacking through the bush? Like, what’s going on?

Dr. Eric Reyier: Oh, so that is the best part of my job is that it’s the diversity. I’m in the field quite a bit,

probably about two to three days a week, but we also do a fair bit of lab work, and not only do we have to catch fish, but we have to write about it, as well — you know, permits and reports and whatnot, but, all in all, it’s a super-diverse project. You don’t know what you’re gonna get into on any given day ’cause issues pop up all the time, and there hasn’t been a single day where I rolled out of bed and didn’t want to come to work.

Joshua Santora (Host): That’s awesome. That’s so cool. So, obviously, it’s probably no mystery now at this point. Like, it is factual that some days we pay you to fish. Is that fair to say?

Dr. Eric Reyier: I’m told I’m not supposed to advertise that — yes.

[ Chuckles ]

Dr. Eric Reyier: So it’s a little bit different. In a way, it’s cheating ’cause we get the permits to fish with interesting gear like long longline and gill nets, where you can catch a lot of fish really fast for scientific purposes, but, also, we don’t take things home.

Joshua Santora (Host): Yeah, exactly, exactly.

Dr. Eric Reyier: Generally, most of the fisheries’ research we do — and we can talk a little bit about this in-depth later on — is nonlethal. We catch fish, we measure them, record them, identify them, and let them go.

Joshua Santora (Host): Yeah, I want to make sure that we are clear to say that it’s not like you’re out here, like, just sitting back just chilling in the boat, fishing.

Dr. Eric Reyier: No, no. Like, you’re out here, you’re doing research, you’re doing science.

Joshua Santora (Host): So, give us some examples of the research that is going on both amongst your team, as well as I know that we bring in other folks to do research in the area, as well.

Dr. Eric Reyier: Yes, yes. So, big picture — if you look at the landscape of the space center, it’s about 65 percent water. So fish are really a dominant part of the ecosystem here. We’ve got a number of — in fact, I think about over 100 species that are federally managed, which means NASA’s got to consult with other agencies when they do construction or modify habitat, and so having that basic information on where fish are, what are the most critical habitats around the space center, that information is important because it allows NASA to minimize the effects of, basically, the space program on the fisheries habitat here. So, some of the specific projects we do — we’re involved in what’s called the Florida Atlantic Coast Telemetry Network. It’s an array of now several thousand underwater listening stations. They’re acoustic receivers, but they’re moored underwater here in the lagoon and along our shoreline here at Canaveral, and so we manage this section of the FACT Array, and we’re teamed up with all sorts of universities, wildlife agencies basically from the Gulf of Mexico up to Canada, and these sensors that are underwater listen for the passing of tagged fishes and sea turtles. We put transmitters — typically, we actually sew them inside the fish. The sea turtle bobs, we work with that. We’ll fiberglass a transmitter on the sea turtle, and they ping about every 90 seconds, and as these animals move through the environment here — the Indian River Lagoon is what’s surrounding the space center, or along the Atlantic coast, which is we border the Atlantic Ocean. As these animals move through the system, we can actually document that those movements, their habitat preferences, their survival sometimes using this system.

Joshua Santora (Host): So why is that important? ‘Cause I think that there’s some people that are lovers of all things fishing, and they can kind of appreciate what you’re doing, but for those that may not really have a background with fish and fishing, like, why does it matter that we track these fish or turtles or the nesting patterns? Like, what does that benefit us?

Dr. Eric Reyier: Sure. So it benefits NASA because now they have a good sense as to what fish we have here, where they spend most of their time, where they’re spawning, where they’re foraging, and, like I said, many of these are federally managed. By knowing that information, you can actually make good choices on how you develop habitat or, if possible, avoid critical habitats. You can gauge the effects of construction activities. We have mitigation sites where we actually open up if there’s work going on in habitat that needs to be altered. We can actually help restore other areas, and we can document that through this network.

Joshua Santora (Host): So kind of switching gears.

Dr. Eric Reyier: Sure.

Joshua Santora (Host): Just thinking about cool stuff that you found, ’cause, obviously, like –

Dr. Eric Reyier: Oh, now we’re talking.

Joshua Santora (Host): The ocean and river and waterways are places of, in a lot of ways, great mystery. Tell us. What have you found that’s really cool out there?

Dr. Eric Reyier: Yeah, so that’s the most exciting part of my job is, you know, we know so much about terrestrial organisms. You know, people have known the details of how, for example, birds make their living. Since the ’50s, they’ve been able to radio-track them…

Joshua Santora (Host):Sure.

Dr. Eric Reyier:…across the continent, and fish are different. Especially around here, the water is just — it’s so murky. These animals — even really small fish — will migrate, potentially, hundreds of kilometers. Learning the details of how they make their living in the ocean has been really hard, and we’re actually sort of at a golden age in fisheries in terms of technology. You can put satellite tags on big sharks that if their fins stick out of the water, they can actually communicate their position and environmental conditions to the satellite and then it just comes into your e-mail. Some of the things we learn specifically, there’s a species called the Atlantic sturgeon, which is on the U.S. Endangered Species List, which is a big deal for a fish. Historically, we thought they were exceptionally rare in Florida — three records in 100 years anywhere off east Florida, and we detected 12 of them last year all from, basically — they were tagged by other researchers doing the same thing that we are up there, but as the animals move along the coast, we’ll detect them, and then we send that data back to these researchers, but tagged, basically, from the Carolinas all the way up to New York. Another cool one is — we didn’t know this until recently, but white sharks, which we thought were actually fairly uncommon here off of Brevard County –

Joshua Santora (Host): Right.

Dr. Eric Reyier: That is absolutely not the case. They are –

Joshua Santora (Host): This is like a warning, everybody who’s listening, if you live near here.

[ Laughs ]

Dr. Eric Reyier: White sharks get all the press. They’re a little too glamorous for my taste, but they do capture people’s attention… and they’re getting tagged all over up in New England.

Joshua Santora (Host): Sure.

Dr. Eric Reyier: But there’s encounters. Every now and again, I have white sharks down here, but it turns out they’re actually really common here every winter. They’re tickling the feet of the surfers, and people didn’t even know it.

Joshua Santora (Host): Huh. So maybe the story there is, we were doing well because nobody has really had a problem until just recently when we’re starting to realize this.

Dr. Eric Reyier: Well, you know, they’ve always been here, I’m sure. So, for thousands and thousands of years, they’ve been making this journey in the winter, and they don’t stop here, necessarily. They keep going, so…

Joshua Santora (Host): That’s awesome. So, these tags you talk about, I know you mentioned that you’re tagging some animals. Obviously, other people are tagging animals. Do people ever find your tagged fish?

Dr. Eric Reyier: Yeah. Yeah.

Joshua Santora (Host): Are they ever, like, fishing somewhere where it’s legal, and they catch one of your fish?

Dr. Eric Reyier: Yeah. So most of the fish that we tag are legally harvestable…

Joshua Santora (Host): Okay.

Dr. Eric Reyier:…and so we sew these transmitters — about the size of my index finger – into the fish ’cause they’ll stay there for years and years, and they don’t affect the behavior of the animal at all, but if a fish is harvested, and the angler decides he wants to take it home and clean the fish, oftentimes this transmitter will fall out, and we’ve learned, hey, put your name and phone number on these things because they’re worth about 300 bucks, and it’s another — if we get it back, we can go tag another fish and increase our data set for sure. And, to be honest, I love those interactions with fishermen ’cause we consider ourselves experts because we do this for a living, but I spend half my time in front of a computer, and talking to these folks, especially the commercial folks and the recreational guides that are around the space center, the guides come from all over to fish around the space center ’cause the habitat is better than anywhere else here in Indian River.

Joshua Santora (Host): Cool.

Dr. Eric Reyier: I learn more in 10 minutes talking to those guys than I do reading journal articles all day.

[ Laughs ]

Joshua Santora (Host): That’s awesome. Very cool. And, obviously, we have to ask the question, have you had one that got away? Like, is there the one that got away?

Dr. Eric Reyier: “One that got away?” Uh, no. In fact, just the opposite. The one fish that I always wanted to catch, and I thought I would never have the chance to do it — it’s called a smalltooth sawfish, which is — I don’t know if you’ve ever seen them. They’re actually more closer related to stingrays, but they have this big saw or rostrum that comes off their snout.

Joshua Santora (Host): Okay.

Dr. Eric Reyier: They get about 18 foot long, and, historically, they were a dime a dozen here in the Indian River Lagoon — a huge problem for commercial fisherman way back in the 1800s, and they didn’t have the ethic that we do now. These sawfish would get into the fishermen’s net, and they would actually — the fishermen would chop the rostrum off, and then the sawfish couldn’t survive, and so the sawfish crashed back in the ’50s. We never thought we’d see one around here, but back, I think, about 2004, we were fishing right off the beach, tagging sharks, I think, and it was the very first set of the very first day of the study…

[ Chuckles ]

Dr. Eric Reyier:…and this sawfish came up on the line, and — ’cause it was always my dream catch, and I’d always announce, “Today’s sawfish day,” and it was a joke.

[ Laughs ]

Dr. Eric Reyier: And then that first line comes up, and here comes this huge sawfish, and it was spectacular. It was mad. Oh, man.

Joshua Santora (Host): How big was that one?

Dr. Eric Reyier: So it was a juvenile. It was about 10 foot long is all, but –

Joshua Santora (Host): That’s a juvenile — 10 feet long?

Dr. Eric Reyier: Yes, yes. Exactly. So…

Joshua Santora (Host): Goodness. What’s the biggest thing you’ve ever seen out here?

Dr. Eric Reyier: We have what’s called a Longline Survey — just ended, but we were surveying right off the Cape so we know what’s around and what’s not around is just as important. We lay what are called longlines, which is — basically, it’s a 2,000-foot string of really thick fishing line that’s anchored on both ends on the bottom, and every 50 foot, you’ll clip a hook on it with some bait, and you let it sit for about half an hour, and then you reel it up on a winch, and we get a lot of little stuff — I mean, they’re big.

Joshua Santora (Host): For sure.

Dr. Eric Reyier: You know, 4- to 6-foot long sharks are really common. Red drum, if you know, they get about 3 or 4 feet long, and so sometimes we’ll set two if the site’s really close together. So we set one, ran to set the other one. We could still see where we set the first one, we thought, but when we got back to pull it, our longline — and you could tell by — there’s floats that mark each end.

Joshua Santora (Host): Right.

Dr. Eric Reyier: It’s nowhere to be seen, and that’s really strange and, really, it gets you nervous when you lose a big piece of gear like that. So we’re looking around, and –

Joshua Santora (Host): We’re gonna need a bigger boat?

Dr. Eric Reyier: Yeah, lo-and-behold, there’s our longline floats just hauling offshore. It takes a really, really big animal to do that.

[Suspenseful music plays ]

Dr. Eric Reyier: And so we caught up to it, and when we caught up to it, I realized whatever had snagged it had snagged it in the middle, and the line had bent around whatever fish was towing it, and all those other fish that were on this longline had now — ’cause it was a really good set. Otherwise, we caught a bunch of other sharks, and they’re all tangled up in this whole mess of longline.

Joshua Santora (Host): Dragging behind this thing.

Dr. Eric Reyier: Yes. And so we catch up to it. We sort of, basically, cleat this line off to the boat. It starts to drag the boat, as well.

[ Laughs ]

Dr. Eric Reyier: And we’re working on these sharks, and we want to get the sharks off and measure them and let them go, and it starts to occur to me that what else can this be…

Joshua Santora (Host): Yeah.

Dr. Eric Reyier:…but a great white shark.

Joshua Santora (Host): Right.

[ Suspenseful music continues ]

Dr. Eric Reyier: ‘Cause, I mean, it was literally towing our boat. So I started getting excited, and so, like I mentioned before, white sharks get a little too much hype, you know.

Joshua Santora (Host): Right.

Dr. Eric Reyier: And so I sort of — It’s like, “Eh,” you know. I played the tough guy like, “I don’t want to see a white shark. You know, they get too much love.” But once I realized we might actually have one, I started getting sort of excited about it. You know, they’re saying, “Eric, settle down, settle down,” but I was very — I was confident this thing was a white shark. And, we finally, after like two hours, we caught up to it, and we got right there. This is the grand finale. And I’ve never seen a white shark in person.

Joshua Santora (Host): Sure.

Dr. Eric Reyier: And it turned out it was a…

[ Suspenseful music continues ]

Dr. Eric Reyier: It wasn’t a white shark. It was a giant manta ray…

[ Water splashes ]

Dr. Eric Reyier:…which is –

Joshua Santora (Host): How giant are we talking?

Dr. Eric Reyier: Oh, they get huge, but they’re supposed to be here, and it just didn’t occur to me that we could have caught a manta ray, and manta rays, they feed on plankton. So what happened, it had just sort of swam into the net, and it got hooked on its fin for a while, and this thing was probably about 15 foot wide. It was a huge animal.

Joshua Santora (Host): Oh. Crazy.

Dr. Eric Reyier: So I would actually circle back to your original question, “What’s the biggest animal you’ve seen?” That’s probably it.

Joshua Santora (Host): Yeah.

Dr. Eric Reyier: But I was, I guess, sort of highly disappointed that it wasn’t a white shark.

[ Laughs ]

Dr. Eric Reyier: And my coworkers bring it up not daily, but quite often.

[ Laughs ]

Dr. Eric Reyier: They don’t let me forget how excited I got about the white shark that I had been ho-humming for years and years, so…

[ Laughs ]

Joshua Santora (Host): Awesome. Well, Dr. Reyier, I appreciate you coming in.

Dr. Eric Reyier: Okay.

Joshua Santora (Host): Thanks for being here. I wish you the best of luck. Thanks for taking care of our environment.

Dr. Eric Reyier: Yeah, this was fun.

Joshua Santora (Host): Thanks for looking out for us, and happy fishing, happy research — all of the above.

Dr. Eric Reyier: Okay. Thank you very much.

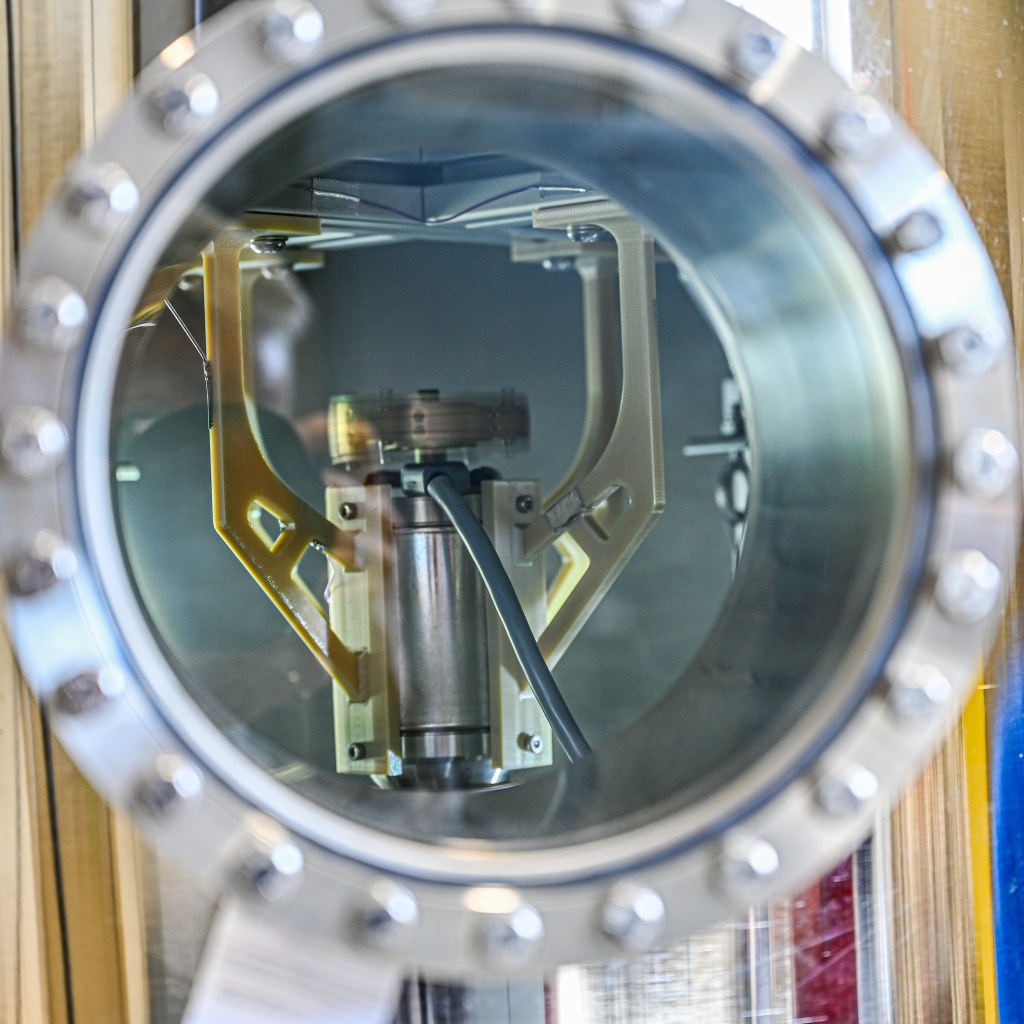

Joshua Santora (Host): As Kennedy’s Exploration Ground Systems ramps up for the first launch of the new Space Launch System rocket, crawler driver Sam Dove with contractor Jacobs puts the behemoth transporter that will take it to the launchpad into gear. All right, I am back in the booth. Today I’ve got Sam Dove. Sam is a driver of our crawler-transporter. So, hey, Sam. Thanks for being here today.

Sam Dove: You’re welcome.

Joshua Santora (Host): To make sure people understand, this is a pretty massive machine. When we talk about you’re a driver of a crawler, that may not sound that large, but we’re talking about you can put a professional baseball diamond on top of the crawler. Is that about right?

Sam Dove: Yeah, you could fit a baseball diamond on top. That’s one of the things that gives everybody an idea, you know, just how big it is.

Joshua Santora (Host): What is the crawler used for? Why do we need such a large-tracked vehicle?

Sam Dove: Well, the crawler’s used to pick up the mobile launcher.

Joshua Santora (Host): Which currently is a massive platform with a massive tower attached to it, which, I think I’m hearing, weighs on the order of, like, 10 to 12 million pounds when it’s done — something like that?

Sam Dove: Yeah. The rocket is stacked in its entirety on top of the mobile launcher. We pick that whole assembly up. The lifting capacity is about 18 million pounds. We carry it out, take it to the launch pad, set it down on the launch pad. Anything big has to be moved, we move it.

Joshua Santora (Host): How do you get to the job of driving a crawler-transporter?

Sam Dove: I worked here for 30 years at Kennedy Space Center — first 10 years in design engineering, and then the last almost 21 on the crawler as an operations engineer.

Joshua Santora (Host): And you mentioned that was because you guys — you’re not just a driver.

Sam Dove: Right.

Joshua Santora (Host): You do a lot of different things, and so the engineering comes in with maybe not so much the driving aspect, but some of the other elements. What else do you guys do?

Sam Dove: Well, I’m also a certified test conductor. The test conductor’s in charge of the operation on the crawler, in charge of all 30 people and everybody you have to have in all the operations. I’m in charge of keeping things going, keeping the flow going right, making sure the checklists are followed. Also, a certified Jacking, Equalization, and Leveling operator. Engineers usually do those three jobs, and part of that, you have to know all the crawler systems, how to repair them, what’s got to happen, what’s wrong, how to troubleshoot if you have to do any mods on the crawler.

Joshua Santora (Host): We know dealing with any machinery, nothing works 100 percent of the time, so, can you give me kind of a feel of what are, maybe, some common issues or what’s maybe, like, the weirdest thing that’s ever happened to the crawler — things that jump out at you?

Sam Dove: Most of the time, it’s well-behaved, and we take a lot of pride in doing our maintenance and everything, but, occasionally, you know, it is a machine. It might have a roller or bearing go out, or maybe you have something go wrong with the generator or maybe a transducer. It’s never the same, right? I mean, the same thing never hardly ever breaks two times in a row. We’ve broken a shoe before, and that single shoe has to be able to carry the whole weight that’s pushed down on it through the rollers. I think everybody’s pretty familiar with a bulldozer or something like that.

Joshua Santora (Host): Sure.

Sam Dove: You can think of that and just take each one of those pieces of that track and just make it about 20 times bigger, right?

[ Laughs ]

Sam Dove: And each shoe does weigh 2,000 pounds, so you definitely have to come to a stop for that. And it can be a lot of things. You just have to go troubleshoot the system, go figure out what’s wrong, and fix it. Now, we have a lot of redundancy on the crawler, as well. So, a lot of times, you can just shut that down and go to the redundant system and continue on. If you don’t have redundancy, then what we have is a big support team behind us, right? When we’re rolling, we usually have everybody that we need to call back and say, “Hey, we need this part — out of stock,” and those folks, they’re great. I mean, they take care of us so good. When it gets there, our techs go change that stuff out. We test it, then back on the road again.

Joshua Santora (Host): Thinking about something like that, how long are we talking? Like, what kind of delay is this? Is this, like, 30 minutes, a couple hours? How do we compare to Triple-A?

[ Laughs ]

Sam Dove: Oh. Well, if they had to come tow, Triple-A would make a fortune, right?

[ Laughs ]

Joshua Santora (Host): Listen. Listen. Is there a vehicle big enough to tow a crawler? ‘Cause I’d love to see that vehicle.

Sam Dove: The other crawler.

[ Both laugh ]

Joshua Santora (Host): So we call it “the crawler,” and I think it’s with good reason we call it “the crawler.” When you open this thing up, and you go full speed ahead, what are we talking about on top speed here?

Sam Dove: Well, it has the power, the electrical power to do 2 miles an hour, but you never would do that, right?

[ Laughs ]

Joshua Santora (Host): So top speed is 2 miles an hour?

Sam Dove: Yeah, well, that’s what all the specifications say, but we’ve never — I mean, I’ve never added up past more than a quarter, you know?

Joshua Santora (Host): Okay.

[ Chuckles ]

Sam Dove: You just wouldn’t want to do that. It’s too hard on the equipment, too hard on what you’re carrying.

Joshua Santora (Host): Sure.

Sam Dove: And you can accomplish the same thing in a slightly slower speed, you know, and get there with less chance of damaging anything. It just takes you an hour or so longer.

Joshua Santora (Host): And what’s the total time on that trip? Obviously you’re not moving very fast. How far is it and how long does it take you?

Sam Dove: Well, it depends. It’s a four-and-a-half-mile trip. Usually seven to eight hours, but the trip in between, it’s everything you have to do to get ready — you know, to get under the load, pick it up, make sure everything’s disconnected, pick it up, carry it out, and then do the reverse when you get there. You know, get it set down, make sure everything’s –

Joshua Santora (Host): Sure.

Sam Dove: And the crawler provides a lot of other services to the mobile launcher — you know, a lot of power and things like that. So there’s a lot of connections and disconnections have to be done. The whole rollout — you know, it really depends on how things go, but it can run anywhere from 16 to 20 hours.

Joshua Santora (Host): And so thinking about kind of a day — this day of your work. Obviously, we don’t move the things on the crawler every day.

Sam Dove: Right.

Joshua Santora (Host): So when it is a crawler moving day, what’s that day look like for you? Like, how does the shift work? Do you sit in the driver chair the whole time? Walk me through a day.

Sam Dove: Well, typically, if we’re moving, we have assignments that we sit down, and myself and another engineer make the assignments. Usually you spend — You could spend anywhere from one to two hours driving, and then we switch and rotate around, and then you come and spend one to two hours operating the leveling system, and if you’re certified, then you come to spend one to two hours as a test conductor, and then other times when you’re not scheduled for anything, you’re constantly on the move or checking systems to make sure everything’s good, make sure we have no problems, and constantly checking with our guys, making sure they’re okay, and, you know, just generally making sure that the mission’s going smooth and the crawler’s all right.

Joshua Santora (Host): And what’s it like inside? So thinking about you’re obviously not driving the whole day. You’re taking on different tasks. What’s it like to be inside. What kind of environment is it?

Sam Dove: Okay, the crawler’s divided up into sections, believe it or not. You have the cabs where you…

Joshua Santora (Host): It’s big enough to, right?

Sam Dove: Yeah, it is.

[ Chuckles ]

Sam Dove: But you have the cabs where you actually drive from. There’s a console in there with buttons, switches, dials, meters and computer screen, of course, and a lowrider-type steering wheel. It’s a very small steering wheel, and — but it’s all fly-by-wire, right? So you spend some time driving in there, and then inside the control room, which is in the middle of the crawler, and on the side, too, you have all the operations, the consoles, everything for the jacking, equalization and leveling. You can see the test conductor is in there, and from there, the test conductor can see everything that happens on the crawler — pressures, temperatures, RPM, what’s running, what’s not. You know, you got a camera system where you can see where everybody’s at, how things are doing in the engine rooms and the pump rooms. You can see how high we are, how low, how fast we’re going, laser-docking things — everything like that — what kind of power we’re generating, how our generators are doing, and how the computers are working out – virtually everything you can see on the crawler’s in the control room. And then, on each end of the crawler, you have an engine room — on engine room 3, and one on engine room 1. We have an Alco engine in there connected to two DC generators, and then we have a Cummins engine connected to an AC generator that provides all our AC power, and then in the middle, the very middle, we have our pump room, which has our jacking, equalization and leveling system motors and pumps and the steering system motors and pumps, and all of the superchargers and things like that you have to have to run the pressure up, and you have about a 2,200- or 2,300-gallon hydraulic tank in the middle that holds all the hydraulic fuel, and then on the opposite end, you have the same configuration of the engines again except they’re just kind of mirrored over. You have an Alco engine on that end and another Cummins engine.

Joshua Santora (Host): Do you know what the fuel efficiency of the crawler is? Any idea?

Sam Dove:Sometimes, you know, the Cummins engines, when they’re carrying a lot of electrical load, you’ll use 35 gallons an hour just on those, and you might see somewhere around 90 gallons or, say, 75 to 90 on the Alco engines depending on the load and how hard you’re running.

Joshua Santora (Host): How long have we been using these crawlers for now?

Sam Dove: Since day one of the — Well, it started with the Apollo Program, and that was one of the main concerns of the Apollo Program – could the crawler actually carry a Saturn V rocket and the tower, right — which you think back to 1963, ’64, ’65, even ’66, it was still unknown, and it was a question whether it could happen, but the guys who designed it, they knew what they were doing — did a real good job with it, made a few modifications here and there, and it’s been able to carry every rocket we’ve had since Saturn V through the shuttle and now up to Space Launch System.

Joshua Santora (Host): So, we’re traveling to the launch pad. What are we driving on? Is this just concrete? Is this a normal road? What is the structure like that you travel on?

Sam Dove: The crawlerway — it’s the size of an interstate, a modern-day interstate, right?

Joshua Santora (Host): Like a full interstate, right — not just like a full interstate lane, it’s a full-width interstate.

Sam Dove: Right — full-width interstate, two lanes on each side and a median in the middle. Originally, they planned to put down asphalt the entire way, but, as it turns out, you know, 12 to 16 million pounds — in this case, 18 million — crushes asphalt up pretty good, and when you try to turn, it kind of heaves it up a lot. So what they found out was that the best thing for the crawler to have is a limestone base with about 8 to 12 inches of gravel on top of that, and so the crawler rides down the crawlerway on this cushion of gravel and also helps with the coefficient of friction in turn, and it smoothes the ride out a little bit, but it makes it easier on what you’re carrying, as well.

Joshua Santora (Host): Just to kind of paint a picture for people, if you drive past the crawler way, if you drive alongside it, at high speeds, it looks like tiny pebbles, basically, filling the crawler way. So, why are we using what we’re using there?

Sam Dove: Okay, think of the gravel on the crawlerway as like the creek gravel you put in your flower beds at home, right?

Joshua Santora (Host): Okay.

Sam Dove: Only bigger.

[ Laughs ]

Sam Dove: Way bigger. They’re not the small pebbles you have, but it’s the same texture, same color. They have the same roundness to them. It’s just larger gravel, right? And they use that to fill the crawler way, the crawler rides on it. The crawler doesn’t have a suspension, so that helps out with the smoothness of the ride, also with the turning and everything, and it helps — it’s easier to groom that type of gravel, too, to keep the crawler way conditioned and fit, and it makes it a lot easier for the crawler leveling system to keep everything level and equal.

Joshua Santora (Host): So thinking about leveling, when you get out to the launch pad, you’re actually driving up a mound, and people have seen images of that. You know that it’s definitely an elevated structure there.

Sam Dove: Right.

Joshua Santora (Host): So, are we tipping our rocket over as we ride up the hill?

Sam Dove: No, not at all. The crawler keeps everything within a couple of inches, right — keeps it level and equal from end to end, side to side, and across. If you think of the crawler having an “X” across it, it keeps it level and equal across there, and as you go up the pad surface on the slope, the front end comes down as low as it can go, and the back end will rise up as high as it can go to its limits, and that way it keeps it very level as you go up and gives it a smooth ride, and as we reach the top of the pad, everything jacks back down and gets it level and equal again, and then we go over the mounts and we set it all down.

Joshua Santora (Host): Cool. Clearly, this is a hulking machine, but how finite is the control? Because once we get up to the launch pad, I think you got to park it in a pretty specific spot, right?

Sam Dove: We do. Yeah, “hulking” makes it sound –

[ Laughs ]

Sam Dove: It’s pretty much of a — the crawler — I can make the crawler go so slow, you can barely tell it’s moving.

Joshua Santora (Host): Hmm.

Sam Dove: Or we can go up to the fastest speed it will let us go — you know, .8, .9, one mile an hour, but it does it, and it will speed up and slow down in a very nice manner, and you have to remember, this is not all computer-controlled. The driver controls it.

Joshua Santora (Host): Sure.

Sam Dove: And once our drivers get proficient, you can speed up and slow down in such a nice manner that the instrumentation — some of the instrumentation guys are watching like, “Wow. That almost looks like a computer did it.”

[ Laughs ]

Sam Dove: You can steer and you can get this thing, you can set that mobile launcher down. Right now — in the Shuttle Program, we were held to a 2-inch circle, right, to set the mobile launcher down, and a mobile launcher has six guide pins that stick down.

Joshua Santora (Host): Okay.

Sam Dove: These guide pins, they’re a good foot across, probably 18-inches long, and you have to put those down on top of the mounts to fit them in the holes, and we can set that down — In the Shuttle Program, again, they allowed us 2 inches — a circle of one inch each way. Well, with SLS, it’s one inch, right? So it makes it a little harder.

[ Laughs ]

Sam Dove: But we can set that down in there. With the crawler, you can get it right up in there, and you can set that thing down left or right or back and forward depending on what — you go north or south. But you can set that down within that one-inch circle, and you can repeat that virtually every time.

Joshua Santora (Host): Awesome.

Sam Dove: Yeah.

Joshua Santora (Host): We’re talking about a vehicle that travels on a very special driveway, probably has pretty unique and specialized parking spaces. Have you ever run into problems getting in somebody else’s way?

Sam Dove: No, no. A number of years ago, one of the security guards out here decided it would make a great joke, you know — which to us was pretty funny. I don’t know, but –

[ Laughs ]

Sam Dove: We parked in a place we don’t normally park. Just sometimes you’ll leave the crawler on the crawler way overnight, or whatever — sometimes at the midfield park site, and sometimes you might be at one of the refurb sites. And so they left a warning on the side of the windshield, right — on the door…

[ Laughs ]

Sam Dove:…and said, “Hey, you guys are parked in the wrong spot.”

[ Laughs ]

Joshua Santora (Host): Hey, Sam, I appreciate you coming in today. Thank you for your and your team’s work. Obviously, if we don’t get to the launch pad, we can’t fly.

Sam Dove: Right.

Joshua Santora (Host): So, you guys are a huge part of what we do here, and thanks for coming.

Sam Dove: I really appreciate it, and the crawler crew, you know, they’re 100 percent behind what we’re doing. Those guys — we have very little turnover. Those guys really stick to their job. They make sure everything works. Basically, when they call us to go do something, that’s what we do.

Joshua Santora (Host): So far we’ve covered land and sea, now to the air. Keeping an eye on the Ranch from up above is helicopter pilot Dave Ramsey.

Joshua Santora (Host): All right. I’m in the booth this morning with Dave Ramsey, who has the extraordinary task of flying helicopters for us here at the Kennedy Space Center. Dave, good morning.

Dave Ramsey: Good morning.

Joshua Santora (Host): And tell me a little bit about yourself, kind of your background, how you got here, and what you do for KSC.

Dave Ramsey: Well, I’m Dave Ramsey. I’m the chief of Flying Operations here at Kennedy Space Center. My day-in-and-day-out job is to be a helicopter pilot and manage the aviation assets here on KSC. So that means I get to fly our helicopters and work with our drone guys to make sure we’re giving you guys the products you need.

Joshua Santora (Host): So, obviously, people know what desk jobs are like, but people don’t know what the job of a helicopter pilot really looks like. So, what do you do when you’re in the air? Are you just flying around, checking things out? What’s going on?

Dave Ramsey: So here at Kennedy, yeah. So we use the helicopters for a number of purposes — primarily, our security. We’re flying around, making sure people aren’t doing things in places that they shouldn’t be or aren’t in places they shouldn’t be, looking for fishermen or hunters who are doing — poaching game or in the wrong areas inadvertently. So that’s the primary mission that we do. We also support our biological guys here — our bioresearch guys who keep kind of their fingers on the health of the wildlife community here — so counting birds, counting manatees, looking at eagles every year, hatchlings — those types of things, making sure that the — or just recording the populations and seeing growth or identifying trends. We help with that. And then, as we talked about earlier, those videos, or if you want a beach-erosion video, and you want to see after a storm, for example, what the impacts were, we take teams up to video and document and just check out the center to make sure. After a hurricane, we always take Mr. Cabana up so he can fly over the center to get a good feel for the safety and when to bring people back and that type of stuff.

Joshua Santora (Host): So you mentioned a couple times people being in places they shouldn’t or other things of that nature. Do you all find people out here a lot? Obviously, we’re in the middle of a pretty big green area, a national wildlife refuge. Do you find people or things that shouldn’t be here?

Dave Ramsey: Yeah. I mean, more than you would think, and it’s, a lot of times, fishermen just in places they shouldn’t be, or we had people picking the saw palmetto berries from the wildlife refuge, which isn’t allowed, so we’ve had to run those guys off and detain people for that sort of stuff. So, yeah, I mean, most of it is just people not knowing, so we just, as politely as we can from the air, ask them to move along.

[ Both chuckle ]

Dave Ramsey: Honk our horn at them and tell them to get moving.

Joshua Santora (Host): So, what do you do when it comes to launch time? I know that we use our aircraft for security and other things, but how are you involved with launches?

Dave Ramsey: Yeah, so as we get back to crewed flight, we’re ramping up now. We’re doing some exercises now for a couple of things. Astronaut support — escort, we’ll do that again, which has been done previously. Security of the air during those flights. So we’ll be ready to respond again. We’ll be up in the air during launches, looking for anyone trying to do damage to the rocket or just make themselves famous. So we look for those kinds of things. People coming into the airspace that’s restricted during those launches is a good indicator that maybe something’s — someone’s not paying attention, “A,” or they’re out to do something bad — and so we do those two things, and we also do the MEDEVAC, CASEVAC in case there is something. If something goes wrong prior to launch or during launch, we are ready. We have one aircraft standing by to be a CASEVAC aircraft to help move personnel to the Trauma One Centers, or wherever directed, basically. Once when we departed the SLF, just as we were departing, there was an anomaly on one of the pads a couple of years ago. We had just departed the SLF, and we were flying towards the beach, flying right for that pad when it exploded. Thinking about that, I couldn’t, in my mind, process what was going on at the time. I was like, “Why is there fire burning right there? What is that about?”

[ Chuckles ]

Dave Ramsey: But the explosion, obviously, people remember how the noise, and so all of our team thought — we had just departed, so they thought that maybe we’d crashed and that explosion was our helicopter, so everyone was on kind of high alert during that for a number — no one knew what was going on just like here on center, as well, I’m sure, but…

Joshua Santora (Host): In situations like that, and others, do you all take on or have training for supporting kind of fires or other, like, extreme situations like that?

Dave Ramsey: So we do have Bambi Buckets, which are firefighting buckets that hang under the aircraft that we can put water on things. It’s not a primary mission we do, but we can support that. Obviously, in that situation, that’s not appropriate, but what we did in that situation is just, we picked up our local fire team, fire chief here, flew them over the scene so then they could talk to the guys on the ground. We actually landed and picked up the on-scene commander, got him into the air so he could look at what was going on, where the fires were — you know, passageways to get to them, pad — those types of things. So we do provide that. It minimizes the risk for those guys, those first responders that have to go in if they can get a safer look from the air before their ground guys have to go in. And then later, we brought the drones in — Mike Downs and his crew brought the drones in to fly, again, that same route and live-stream it to the convoy commander’s team or there on the ground so they can get a look and figure out kind of what their plan of attack would be to get their people in there. So it’s a good coordination effort between all of the aviation assets here on Kennedy to help out the Air Force, as well.

Joshua Santora (Host): Yeah, and I want to make sure to be clear that nobody was injured in that incident. Obviously not a great day for losing a rocket and a spacecraft, but there were no people injured that day, which was great. And pretty early on for your time here, right?

Dave Ramsey: Yeah.

Joshua Santora (Host): So that had to be a little bit stress-inducing like, “Hey, like I’m not very long on the job here, and I’m dealing with a serious issue like this.”

Dave Ramsey: Yeah. I mean, in those times, everybody just wants to help, you know, so — but you don’t want to get in the way, but we do believe that having that platform, having an aerial platform here on the center gives you the ability to see the things during those times and really provide insight that can guide those responding personnel, keep them safe, and keep everyone safe. So I think it’s nice to be a part of that team that could provide answers when things get a little crazy.

Joshua Santora (Host): So, Dave, how are you guys involved with the wildlife that is out here? I know that there’s a big effort there. Obviously, again, because it is a wildlife refuge that the view from the sky is very helpful in a lot of ways. So how are you guys involved with that?

Dave Ramsey: Yeah, so we do a lot of overflights of, like, Mosquito Lagoon and the rivers. It’s hard to count manatee from any other way, you know, than looking down on them from the water. So we’ll take the guys up and fly so they can count and get routine counts to see what the population’s doing, when they’re migrating — those types of things. So we do that. At least once a month we’ll take the guys up for a couple hours and fly pre-patterned routes that we fly every time. It’s the exact route every time just to try to keep a consistent count going so they can form those trends and see what’s going on with the health of the wildlife.

Joshua Santora (Host): Dave, I appreciate you being here this morning. Good luck out there, be safe, and thanks for all you do for us.

Dave Ramsey: Yeah, awesome. Thanks.

Joshua Santora (Host): Clearly, we need more than just rocket scientists to get the job done. Maybe your path will lead you here to join our rowdy band of pioneers. I’m Joshua Santora, and that’s our show. Thanks for stopping by the Rocket Ranch. And special thanks to our guests — fisherman Dr. Eric Reyier, crawler driver Sam Dove, and helicopter pilot Dave Ramsey. To learn more about all the cool things going on at the Kennedy Space Center, go to nasa.gov/kennedy. There are also several NASA podcasts you can check out to learn more about what’s happening at all of our centers at nasa.gov/podcasts. A special shout-out to my colleague Laura Aguiar, to our producer, John Sackman, our soundman, Lorne Mathre, editor Michelle Stone, and our production manager, Amanda Griffin. And remember — on the Rocket Ranch even the sky isn’t the limit.