SOFIA Project Scientist Naseem Rangwala discusses the Stratospheric Observatory for Infrared Astronomy.

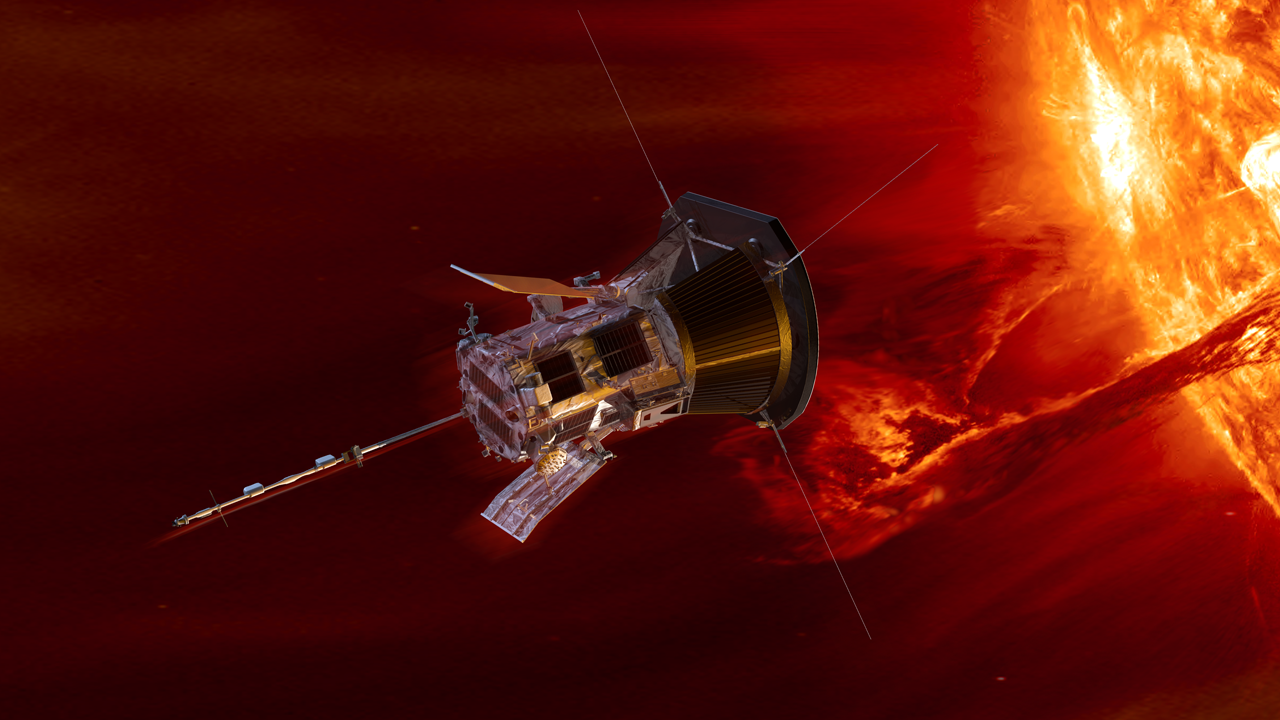

Naseem Rangwala: SOFIA is currently the only astronomical observatory, on or off this world, that can observe the universe at longer infrared wavelengths.

It is also the world’s largest airborne observatory, and it’s the only airborne platform with a telescope on it.

In addition to being this amazing astronomical machine that SOFIA is, SOFIA is also an engineering marvel.

The great potential of SOFIA to make discoveries and study the mysteries of the universe drives me towards mission success.

Deana Nunley (Host): Welcome back to Small Steps, Giant Leaps, a NASA APPEL Knowledge Services podcast where we tap into project experiences to share best practices, lessons learned and novel ideas.

I’m Deana Nunley.

SOFIA, the Stratospheric Observatory for Infrared Astronomy, is a joint project of NASA and the German Aerospace Center, DLR, that has been used extensively to look at numerous objects in the universe, from black holes to galaxies and even the Moon.

Naseem Rangwala is the SOFIA Project Scientist and joins us now. Naseem, welcome to the podcast. Thank you for being our guest.

Rangwala: Hello, Deana. I’m really excited to be here and talk about SOFIA today. Thank you for having me here.

Host: Absolutely. What is SOFIA?

Rangwala: SOFIA is an astronomical observatory that allows us to study the universe at infrared wavelengths. The mission of SOFIA is to make fundamental and impactful scientific discoveries. Generally speaking, SOFIA does that by measuring the physical and chemical conditions of the regions where stars and planets are born. So, when stars are in their infancy, they’re embedded in a cocoon of dust and gas. This is why we need the infrared wavelengths, to peer through that cocoon and study this really important phase of star formation.

SOFIA also investigates path to life by detecting chemical fingerprints of key ingredients of life in interstellar space and in our own solar system, molecules such as water, methane, other carbon and nitrogen-bearing species. And then using these molecules to understand their formation pathways and path to making bigger molecules, prebiotic molecules needed to form life. SOFIA also studies astrophysical processes in galaxies and black holes. You may have heard recently, SOFIA’s now studying the Moon. And I’ll be very excited to talk about that later, if you like.

But also, I want to make a point that in addition to being this amazing astronomical machine that SOFIA is, SOFIA is also an engineering marvel. It is a highly modified Boeing 747 with a 2.5-meter diameter telescope on it. The telescope is the same size as the size of Hubble. SOFIA has a complex suite of instruments and that allows us to investigate a broad range of topics in astrophysics. So, in addition to scientific and engineering marvel, I always like to make this point as well. That SOFIA’s mission is accomplished by a team like no other mission in astrophysics or even beyond. And I’ll be happy to talk about that.

Host: Wow. There’s so much that we want to talk about. You mentioned the Moon. We definitely want to get to that as we go along. Could you tell us more about the impact of SOFIA?

Rangwala: Oh, certainly. SOFIA has impacted many areas. I will point out three areas here. Scientific, of course, engineering, and the public. So, talking about the scientific impact. SOFIA’s mission, the best ideas on what we observe with SOFIA comes from our science community, primarily astrophysics and the planetary science communities. And we have so far served more than 1,500 scientists of all career levels. And so that’s the impact we are making.

When you get time to observe in SOFIA, which is quite competitive, you also get funding from NASA to help analyze these data and publish them. And again, this is true for all astrophysics expeditions. And what this allows us to do is really help empower, especially the early career scientist community. I was one of them when I started my post-doctoral phase of my career. I got my first NASA grant through SOFIA when I was a user of SOFIA, not the project scientist, and that empowered me. And so that’s really one of the biggest impacts that we make to our science community.

SOFIA has a suite of instruments, as I described earlier. And when you build these instruments, you involve students, post-docs, mechanical and electrical engineers during this development. So, we are training the next generation of scientists and engineers to build these cutting-edge, complex instruments.

Engineering. Let’s talk about that. That’s really broad impact, right? SOFIA’s platform is an aircraft. So, in addition to mechanical and electrical engineers, we have aerospace engineers and aviation expertise. And so, a lot of our team members I have learned, because I’m still a newbie to SOFIA compared to folks who’ve been on SOFIA for a long time. So, what I have found is that a lot of our team members who’ve trained and gained valuable experience working on different phases of SOFIA mission, that has led them to bigger and better things, both at NASA and outside of NASA.

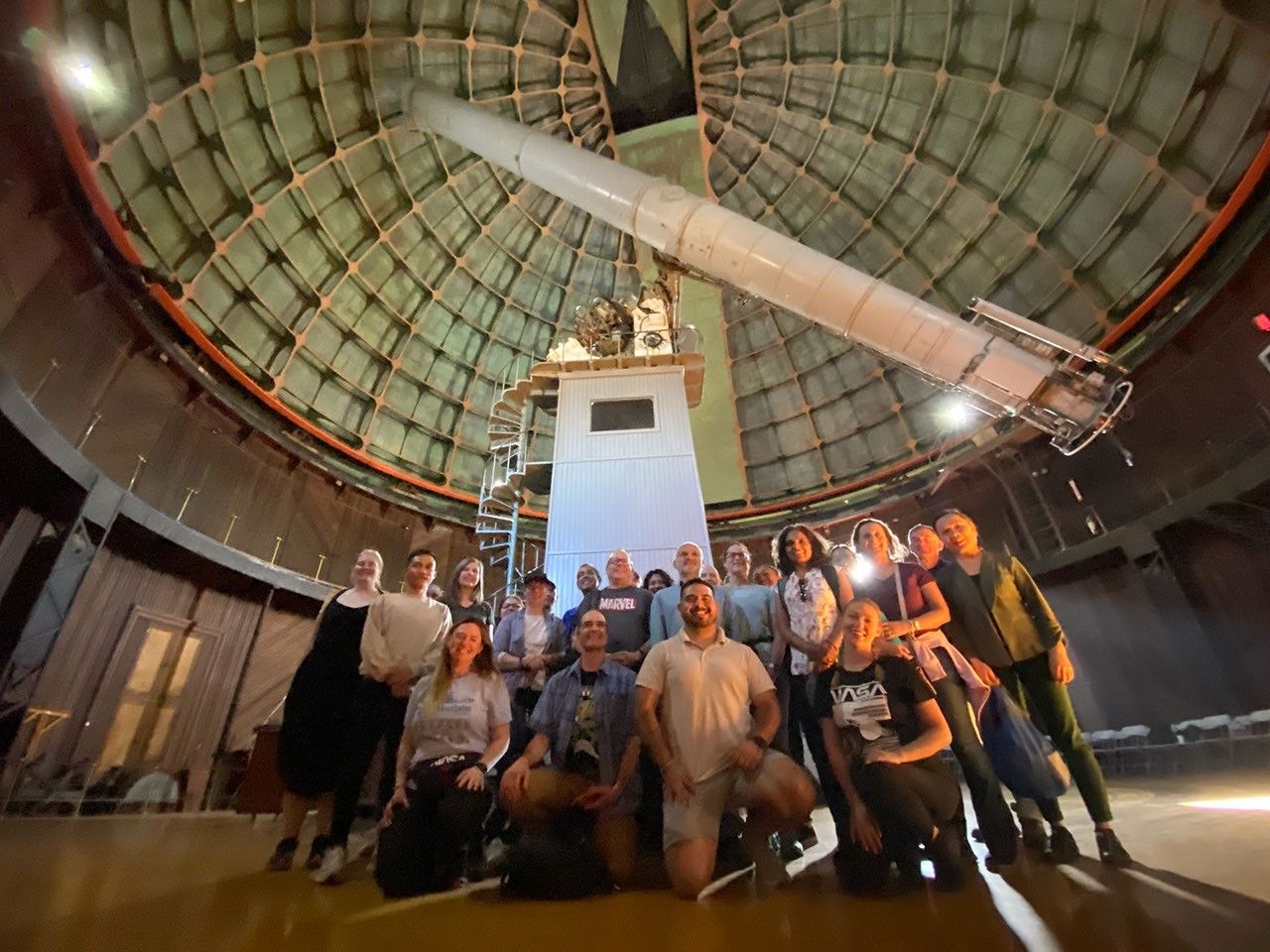

Let’s talk about impact on public. Public, from what I have seen over the last two years, they’re fascinated by both the science and the whole telescope on an airplane thing. Who cannot be? We have flown more than 150 educators on SOFIA, and through that, we have already reached more than 15,000 students in schools across the United States.

Host: That’s amazing. Naseem, what makes SOFIA unique?

Rangwala: So, SOFIA is currently the only astronomical observatory, on or off this world, that can observe the universe at longer infrared wavelengths. And here, we’re talking about a few tenths of micrometers to hundreds of micrometers. It is also the world’s largest airborne observatory, and it’s the only airborne platform with a telescope on it. As technology advances, something that’s unique to SOFIA compared to other space-based astrophysics missions is that we can upgrade SOFIA’s instruments and even build new instruments, and we have done both of them already. And this is, again, not easily possible for space missions. Hubble is an exception. And so, this quality or this characteristic of SOFIA allows us to stay at the forefront of scientific discoveries and allows us to support studies and investigations being carried out by other NASA missions.

In other aspects SOFIA is unique, which I’ve already mentioned, is that it’s unique in astrophysics. It is the cross section of aircraft operations and science operations. So, we get to interact with pilots, engineers, flight planners, scientists, mechanics and technicians who work together every day to launch a mission, or every night. And again, because we are a flying observatory, what makes us different from other observatories around the world is that we can go to other places to observe. For example, we can go to the Southern Hemisphere to observe the Southern Skies. We have some really popular and important astronomical targets in the Southern Hemisphere, or in the Southern Skies, that we cannot access from here. So, we fly to the Southern Hemisphere every year to do that.

Host: What are the top discoveries from SOFIA?

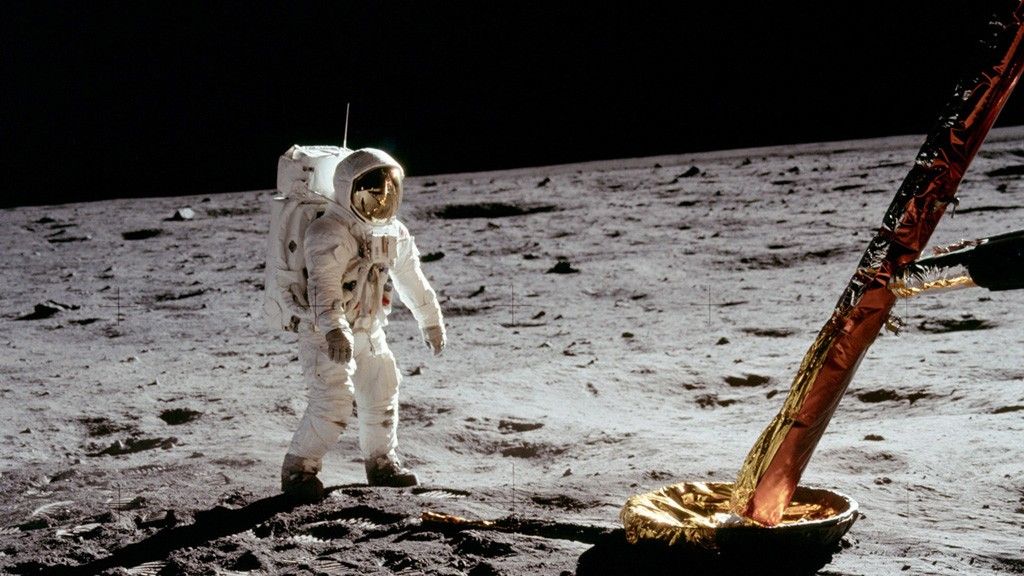

Rangwala: There are some amazing discoveries that I would like to talk about. It’s kind of the hard one because they’re all my favorite. So, I’ve got to start with the most recent one that a lot of people have heard about, when SOFIA detected water on the sunlit surface of the Moon. We did this by detecting the 6.1-micron spectral feature that is unique to water molecules. This was a surprise, as scientists did not really expect water molecules to survive the harsh conditions on the surface of the Moon. So, this was a groundbreaking result that got a lot of attention from media and the public, and I cannot tell you how many events I have done since then. It has been just wonderful to talk about this discovery with the public, especially students.

Another one of my favorites that has made a lot of impact is the discovery of the first type of molecule that ever formed in the early universe. This molecule is called the helium hydride. Scientists have been searching for decades for this molecule, and a key and a relatively quick upgrade of one of our instruments led to this discovery.

Another topic that is making a lot of impact is our magnetic fields in the universe. SOFIA has the ability to map magnetic fields now, and this is a relatively new capability. What’s really important here is that this capability on SOFIA allows us to measure the cleanest signal of polarized light being emitted by dust grains in the interstellar space. And through that, we can infer magnetic fields and their strength. This is new, and we are building an inventory of results that are showing to what degree these magnetic fields impact the formation of stars, and even structures of galaxies.

So there have been a lot of results in the last year, and if you want to learn more about them, they are on nasa.gov/SOFIA. But some of them, I’ll describe very briefly here. We can study material around black hole and what the impact of magnetic fields are on them. And are they helping to keep the material intact around the black hole?

And then also, a very recent result that was out on nasa.gov was about a galaxy that has this super galactic wind. You can think of this as huge amount of material being expelled out of this galaxy. And so, using techniques from heliophysics, actually, we expanded that technique and applied it to astrophysics, and used this capability on SOFIA to understand the nature of magnetic fields on a much larger scale than possible before. And what we are finding is that in this galaxy in particular, magnetic fields might be responsible for helping us to expel material out of this galaxy, into the intergalactic medium. And why do we really care about this? Because we want to understand the life cycle of the galaxies, how they form and how they evolve. And so again, please check out nasa.gov, where you can read about these exciting results, and we have more coming up.

Host: It’s so exciting to hear about all those discoveries. Let’s talk more about the discovery of water on the Moon. How did you react to that when you found out, wow, this is the data we’re getting back, this is what we’re seeing? What was your reaction to that?

Rangwala: Oh, I was absolutely thrilled. We were thrilled and completely surprised because SOFIA, the observatory itself, was not made to observe the Moon. We never even thought of observing the Moon. And this is why I love the ideas when they come from my science community. One of the lunar scientists thought of this. Hey, we should use SOFIA, and they applied. This was a risky observation for us, and I’ll tell you why. Because again, as I said, the observatory is not really made to do such observations of the Moon. First, the Moon is really bright for us. And also, we have to maneuver our telescope in a very different way to precisely track the position on the Moon where we are trying to get the data. So, we had to maneuver our telescope in a very different way than we have ever done before.

We did not even know during that flight if our detectors would saturate or if our guide cameras would saturate. And if that happened, what would be the consequences of that? So, we did this observation towards the end of the flight. I was not on that flight, but what I have heard is the reaction was absolutely of complete excitement when the scientists, and even for other folks on SOFIA started seeing data come through, and the data made sense at that time. But then it took, of course, several months before we knew if we were seeing a positive detection, as with any other scientific investigation. And so when I, at least, found out that this is a positive detection, we were thrilled.

Again, this kind of work doesn’t just impact the lunar community, the science, but also our goal of exploration. Because if SOFIA is able to provide key resource maps of water on the Moon, it can help missions like VIPER and it contributes towards the goal of the Artemis mission.

Host: What factors into flight planning and determining what to observe?

Rangwala: So, I think I mentioned this a little bit earlier, and I can go into it in more detail. What we observe comes from the science community. SOFIA is community’s observatory, just like Hubble and Chandra. So, we release a call for proposal every year. Scientists around the world submit their best ideas that are selected to a peer review process. Then the selected proposals go into a planning and scheduling software that lays out a preliminary schedule, or a whole year, with different instruments. And by the way, we start this a year and a half in advance. It requires a lot of planning. And then this preliminary schedule, it gets fine-tuned as we get closer to starting the observing cycles.

Flight plans are generated about two months in advance. And great care is taken when we build these flight plans, because we want to optimize this very valuable time on each flight and ensure that our best science — we call it the highest priority science — has the highest chance of being completed. And so again, these flight plans are also continually updated up to about 24 hours before the flight and sometimes even closer, depending on weather forecast. Our flight planning is also impacted when we have time-critical observations, such as occultations or other astronomical, like if you are trying to observe a planet that’s about to set early or if you’re observing comets, et cetera. So, we require special care when we are doing those time-critical observations.

Again, our flight operations home base is in Palmdale, California, so our flight plans are made in a way that allows us to return to Palmdale every morning. But we can give exceptions for science program that have very high merit, and we can organize a short deployment in order to capture those astronomical events, if justified.

Host: You mentioned Palmdale, but also, you have a connection with Germany, right?

Rangwala: Yeah.

Host: And so, have you recently started a new series of SOFIA science flights out of Germany?

Rangwala: Yes. And so let me talk about a little bit. We have a very strong connection with Germany because DLR, the German Space Agency, is a 20 percent partner of SOFIA. So, SOFIA recently completed, and we are very excited to inform, the first multi-flight science campaign from European soil. These flights were carried out from Germany last month. And so, this was even extra special, right? We were flying out of Cologne, where headquarters of DLR is. So, the series worked out really well, better than we expected. SOFIA was scheduled to go to Germany for planned maintenance with Lufthansa Technik. And just before SOFIA left, we made a decision to conduct science flights out of Germany. At the time, there were skeptics, and rightly so. Because of COVID-19, there were good reasons to doubt if we could successfully deploy our team to Cologne, Germany. But our team was determined, and with the support from our German partner, again, DLR, we were able to organize this deployment in record time. We completed 15 flights out of Germany and got excellent astronomical data.

All types of community are impacted by the pandemic, as you know, in one way or another or in many ways. Astronomical community was impacted too and has continued to be impacted. Closures of many ground-based observatories. It impacts all career levels, but especially early- to mid-career whose research funding and careers depend on data from these observatories. SOFIA figured out a way to start operations with new safety protocols designed to keep our team safe, but also allow us to continue to take scientific observations. And so, our goal at this point is to provide and collect as much scientific data as possible. This preparation allowed us to go to Germany and finish our best science for this year.

Host: As you talk about the science, we can really hear the energy in your voice. I want to ask you what your perspective is, as a project scientist, that might be helpful to other NASA project scientists.

Rangwala: Wow. Yeah, I really enjoy being the project scientist of SOFIA. This is my first assignment as a civil servant, and I am so grateful for this opportunity. In my role, I am the chief scientist of the observatory. I’m describing my role just for folks out there who may be thinking about applying for a position like this in the future. So, in my role, I am the chief scientist of the observatory. My responsibility is not only to preserve and maintain the scientific integrity of the mission, but to always think about maximizing the scientific potential of this amazing mission and leading the way to achieve as much science as possible and the best science as possible. But my passion, and really the best part of my job, is to enable scientific discoveries by working with a very diverse team. And also, my other passion is to communicate these discoveries in a way that we can continue to inspire the next generation of scientists and engineers.

So being the project scientist is truly a unique experience for a scientist. It’s a great opportunity to make an impact on a much larger scale than you would. When I was a scientist, a post-doc, I would work with other scientists, but never would work with engineers, and never had the opportunity to make impact like this. You’re working and very focused on your research. But here, you are thinking about serving the community and figuring out how you can best enable these scientific discoveries. So, it’s a really different impact you’re making and it’s really amazing. It gives you an opportunity, this position, to grow in so many different areas and as a leader. So, I love serving the community. It has been an amazing experience and growth for me. I’m also very grateful to get this opportunity much earlier in my career than it usually is to be the project scientist of a flagship mission like SOFIA. So, I encourage other scientists, if you have the opportunity to serve as the project scientist, please try it. It’s truly amazing.

Host: Early on in our conversation, you mentioned the uniqueness of the team. Could you talk more about the SOFIA team?

Rangwala: SOFIA team is truly exceptional. It energizes me every day. I never thought that when I was a scientist, what it would be to work with a team like this. I didn’t even know what I was missing, to be honest. And so, on SOFIA, as I said, it’s a cross section of so many different expertise. We have a science center at NASA Ames where we have scientists, data analysts, people who are preparing the pipeline when the data comes from the aircraft, all the way to scientific results, providing that to the community, doing science community outreach, public outreach.

But then we have a whole family down in Palmdale where operations are happening. So, you have, of course, folks who are taking care of the aircraft, and they are always in communications with us. It’s an amazing experience for them to know about the whole scientific world, and they are truly driven by science and the purpose of this mission. So, they are working so hard to ensure that we have a successful mission every night that we launch.

And so, you get to interact with so many different kinds of people on SOFIA. This truly exceptional team is what has made it possible for us to make these scientific discoveries. But also, during these difficult times of COVID and a pandemic like this, we needed a team like this to really come back to operations.

Host: What’s the role of women on SOFIA’s leadership team?

Rangwala: It’s actually quite strong. I am the project scientist. And the director of the observatory, the SOFIA Science Center, is also a woman. Her name is Margaret Meixner. And my counterpart in DLR, Alessandra Roy, is a woman as well. So, we have strong women leadership on this project, and it’s not just at the leadership level. Our team is very diverse. We have women in our Mission Operations team who are flying with SOFIA on many missions to operate the telescope, the instrument. We have mission directors who are women. We have our instrument scientists. That’s becoming more diverse, at least speaking of gender diversity, we have more women there. So, we have women contributing to many aspects of this mission.

Host: From a personal standpoint, what drives you toward mission success?

Rangwala: There are so many things that drives me towards mission success. I didn’t even know this until, actually, I started thinking about this over the last year. The great potential of SOFIA to make discoveries and study the mysteries of the universe drives me towards mission success. The community drives me, this community that puts in all this hard work into proposing important and very cool scientific investigations. You want to get them done. The exceptional SOFIA team, the resilience and determination, drives me. My own scientific curiosity drives me. The little difference that I can make to advance the knowledge of humankind and of the cosmos. But finally, my family drives me. I have a very supportive family. I have two little girls and my husband, and of course, my parents. They look up to you. They’re so proud of you. How can you not work towards mission success with that?

Host: For sure. Will you share your story and the journey that’s brought you to the point of serving as the project scientist?

Rangwala: It has been quite a journey. When you start the journey, you never know what you’re going to end up, and so you just have to continue to dream. So, I started my journey, I would say, when I was 16 years old, in a small town in India where there was not really much exposure to astrophysics or astronomy. I didn’t know anything about it. When I was 16, I read a chapter in my textbook. There was only one lonely chapter on astronomy, and that did it for me. That chapter talked about distance scales in the universe, and it showed calculation to the next star to the size of our galaxy to the distance to another galaxy, and about the distances to early galaxies.

So that made me feel there is so much to learn and know about space, and how insignificant we are compared to all of that. And so that triggered something in me, and that’s how my interest in astrophysics started. And the only thing you know at that point when you’re a kid in a small town somewhere is NASA, right? But you don’t know how to get there. You don’t know anything, but you just start your journey there and you slowly make your way. And you may not end up at NASA. You may not even end up doing astrophysics. But that triggers something in you, at least curiosity to pursue something, or at least a career in STEM. But definitely it triggers the curiosity in you to pursue your career and pursue bigger things and bolder things.

So, I started there and then I made my way up slowly. I left my town. I did my bachelor’s in physics. And then I left India and went to England and I changed my field a little bit. Like I said, you don’t know where you’re going to, you have to do zigzag your way through your journey. I was interested in particle physics at the time. And then I came to the US, and then of course, I was back to astrophysics, and I did my Ph.D. and made my way up. And when I came to NASA Ames, I had a NASA postdoctoral position. And after that, I was offered to serve on SOFIA. So that’s been my journey. And as I said, it’s an amazing journey. I still pinch myself sometimes.

Host: Oh, I can only imagine. What are the future plans for SOFIA?

Rangwala: We have really exciting things coming up. SOFIA will be observing the Moon again and will be this time mapping many more locations on the Moon, both the South and the North Pole. Because after we made that discovery of water on the solar surface of the Moon, we want to do more. We want to find out more about the distribution of these water molecules, and to understand more how these water molecules can survive on the sunlit surface. So, we have really exciting observations coming up, so stay tuned for that. As I talked about, magnetic fields in the universe, we’ll be mapping that in many more targets, so that’s coming up too. SOFIA is planning a Southern Hemisphere deployment, and that’s coming up in the summer.

We are also trying new things to make our observatory and operations even more efficient. We will be going to Southern Hemisphere even more per year starting next cycle, because there is so much demand from the community and it allows us to access different targets. We will be trying something called suitcase deployment in a year’s time. I’m excited about that. We are also adding additional contingency flights to help complete more programs on SOFIA so that we can, as I said, what drives us is making sure we get the community what they asked for. And so, we are trying new things on SOFIA, and I’m very excited to try them and see how we can maximize the potential of this observatory.

Host: Sounds exciting. Could you tell us more about suitcase deployment?

Rangwala: Well, suitcase deployment, we still have to try this out. Suitcase deployment is something quite different from a long deployment that we do every year annually, where you can think about, we just move our base from Palmdale, California, to Christchurch, New Zealand. So, we take our entire team there and we’re there for a couple of months observing. Suitcase deployment will be a bit different. It’s a shorter amount of time that you’re spending outside of your home base, fewer flights. By suitcase, I mean you take everything you need on the aircraft with you. And so, you’re not really changing your base or moving your base, but you’re doing with what you have on the aircraft. You fly those eight to 10 flights and you come back home. So, it’s a different way of doing deployments, and that will allow us to visit Southern Hemisphere more with different instruments. So, we’ll still continue our long deployment, but we’re adding more time in the Southern Hemisphere by figuring out how to do these quick suitcase deployments.

Host: Do you get to actually go on some of the flights?

Rangwala: Oh, yes, and I love that. I am missing that right now quite a bit. For a whole year, because of the pandemic, we wanted to really limit the number of people on the aircraft, of course. And I miss that. Every time I’m flying on SOFIA, I’m in this zone of just inspired and just excited to be on the aircraft. It never gets old for me. Deana, when you enter the observatory, it’s a Boeing 747SP. You have no idea when you enter it for the first time what you’d expect. It’s much bigger. It looks much bigger on the inside because you don’t have the seats or anything. You have all these mission systems and other things. It’s a very different feel on the aircraft. I call it my time machine, actually, sometimes, using Doctor Who analogy. It’s bigger on the inside. If you’ve seen Doctor Who time machine. But anyway, yes, I do get to fly, and I love it.

Host: Sounds like just so much fun. And this has really been fun today, getting to talk with you and learning so much more about SOFIA. Thank you, Naseem, for taking time to talk with us.

Rangwala: Oh, it’s my pleasure, Deana. And thank you for giving me the opportunity to talk about SOFIA and about myself. I hope that we continue to make discovery and inspire the next generation.

Host: You’ll find Naseem’s bio and links to related resources on our website at appel.nasa.gov/podcast along with a transcript of today’s episode.

For more information and conversations about what’s happening at NASA, check out other NASA podcasts at nasa.gov/podcasts.

If there’s a topic you’d like for us to feature in a future episode, please let us know on Twitter at NASA APPEL – that’s APP-el – and use the hashtag Small Steps, Giant Leaps.

As always, thanks for listening.