White Sands Test Facility Manager Bob Cort discusses the history and capabilities of the NASA facility.

Bob Cort: I think we’ve successfully shown time and time again that we’re able to provide a valuable test capability for the programs. They get a result and a value for their money that they can’t get elsewhere.

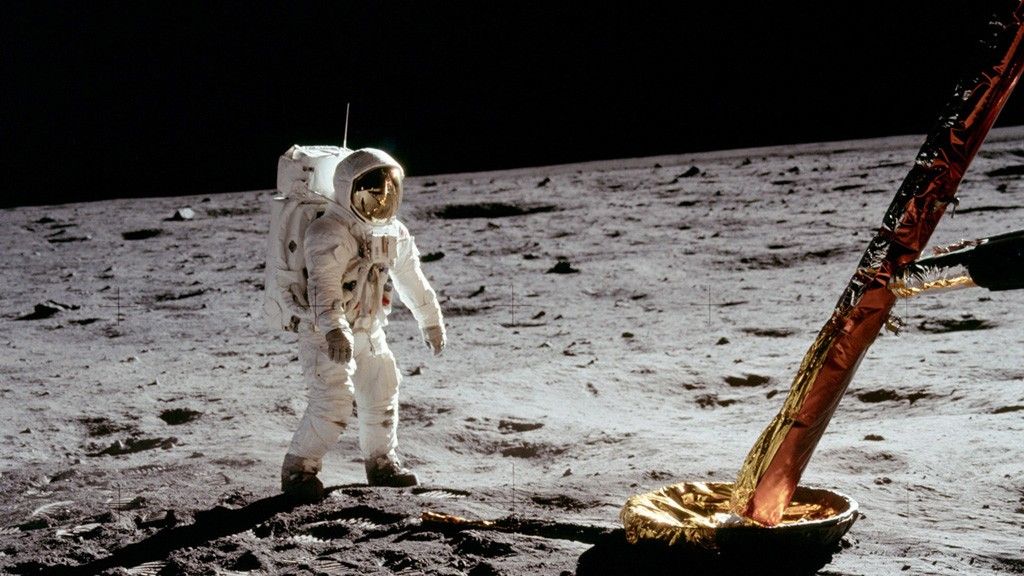

WSTF was built to provide testing for man’s first foray to the Moon and I really believe that we’re going to be a vital part in man and woman’s next foray to the Moon.

Deana Nunley (Host): Welcome to Small Steps, Giant Leaps, a NASA APPEL Knowledge Services podcast that taps into project experiences to share best practices, lessons learned and novel ideas.

I’m Deana Nunley.

NASA’s White Sands Test Facility in New Mexico conducts hazardous testing primarily in support of human spaceflight programs. The facility is a component of Johnson Space Center and provides test services to NASA, the Department of Defense, other government agencies and private industry.

Bob Cort is the White Sands Test Facility Manager and joins us now. Bob, thank you for being our guest.

Cort: Thanks. I’m really excited to be here and have the opportunity to talk to your listeners.

Host: We’re eager to hear about what’s going on at White Sands test facility. Let’s start with some background information. Could you tell us about the history of the facility?

Cort: Sure, Deana. Well, the White Sands test facility, which most of us just call WSTF, was built starting in 1963, primarily to support the Apollo program. We were heavily involved in the testing of the propulsion systems for the service module, which is the vehicle that took the astronauts from low-Earth orbit to the Moon and back, and also the lunar assent and descent stages, which as you know, those are the stages that took the crew down to the surface of the Moon and got them safely back from the surface of the Moon.

Host: What are WSTF’s core capabilities?

Cort: We have seven core capabilities that mostly were born out of the origins of the facility back in the Apollo days, and some were developed as an outcome of things that were determined to be needed as we went on with the manned space flight program. I’ve already hinted at one or two of them and that is the rocket propulsion testing, specifically the in-space propulsion systems that are designed to work in the vacuum of space. And those usually use, but not exclusively use, the hypergolic propellants — dinitrogen tetroxide and the hydrazine families of fuels.

We also do oxygen system and materials testing and analysis. The oxygen testing capability was really born out of the tragedy of the Apollo 1 fire when people here and throughout the agency realized that we didn’t fully understand the hazards associated with high pressure oxygen in a manned space flight environment.

Related to those two is propellant and aerospace fluids. This capability is fairly broad and it includes the ability to do everything from basic chemistry analysis on energetic fluids like propellants as well as to be able to test materials and components that are exposed to propellants or other energetic fluids.

I’ll give you a couple of unique examples here. We recently tested a chemical oxygen generator for the British Royal Navy that was used in a submarine. And you’d kind of wonder what’s NASA doing testing submarine chemical oxygen generators? Well, interestingly enough, we use those same types of chemical oxygen generators on the International Space Station and another spacecraft as backup oxygen generators in case the primary systems fail. So, not only were we able to help the Royal British Navy determine the cause of their fatal accident, but we also improved the safety for our astronauts in space.

We also do flight acceptance standard test. The flight acceptance standard test capability is really related to the other capabilities that we have and allows us to develop standardized test methodologies for both fluids and materials that are going to be used in spacecraft to ensure the safety of our crews. These are all documented in NASA Standard 6001. The team that’s involved in standard test, or flight acceptance standard test, as we call it, can also do custom testing. For example, flammability testing in laptop batteries.

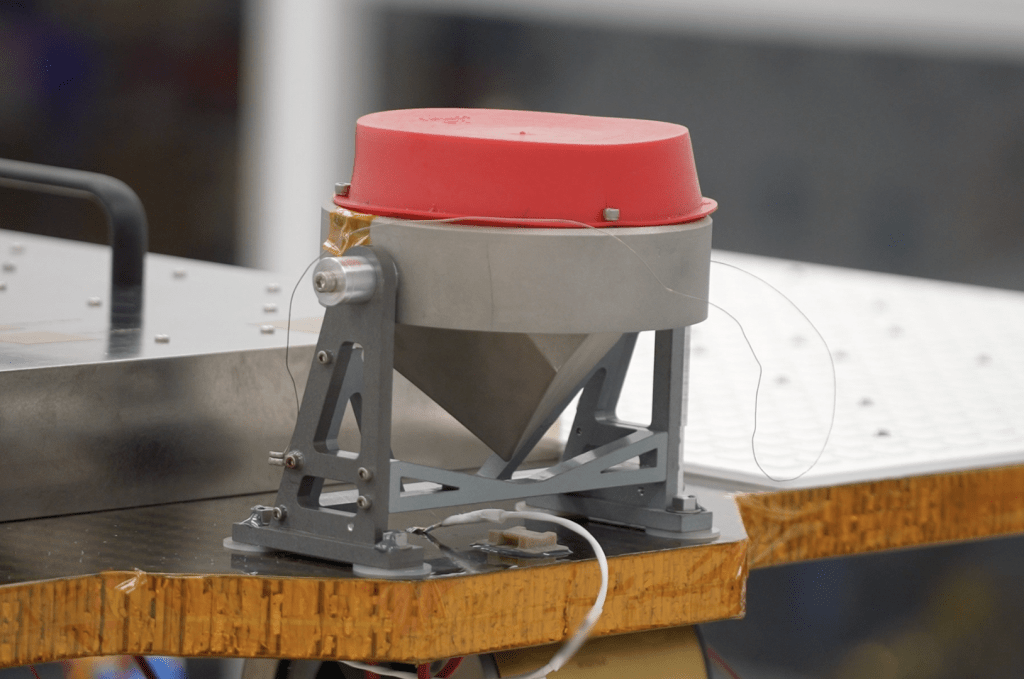

One of our other core capabilities is composite pressure systems. And I’ll be honest. I don’t really know the full history of how WSTF got involved in composite overwrapped pressure vessel testing. But I believe it started when people began to wonder about the potential damage to composite pressure systems caused by micrometeoroids and orbital debris. This capability has really evolved into not only evaluating the hazards associated with COPVs, but teaching classes so that other organizations using COPVs can evaluate them for damages and hazards associated with their use.

Hypervelocity impact testing is our sixth core capability and White Sands Test Facility has the agency’s hypervelocity impact test guns that allow for evaluation of micrometeoroid and orbital debris damage on spacecraft materials and components. This is really important to ensure that we’ve got adequate shielding on critical components for the impacts of debris that are too small to track and avoid by spacecraft. We can shoot projectiles ranging from about 50 microns in diameter, which is about half the thickness of a human hair, up to about one inch in diameter, at velocities approaching about 10 kilometers per second.

And lastly, critical spaceflight hardware processing. This capability really evolved around something that we did during the Space Shuttle Program, which is refurbishment and repair of all of the components that were wedded with hypergolic propellants in the space shuttle orbiters. After the retirement of the space shuttle, we essentially divested ourselves of this capability until the Orion Program came along and wanted to reuse some engines that were harvested from the space shuttles at their retirement. We’re now refurbishing that hardware for the Orion Program, as well as refurbishing some hardware from shuttle and other programs for some different customers.

And I would say that the common thread that runs through all of these core capabilities is that they either involve hazardous testing or they require the knowledge and unique understanding of highly hazardous or energetic materials.

Host: Is that what sets White Sands apart from other NASA testing facilities?

Cort: I think a lot of the other NASA facilities have some similar capabilities and certainly some of the capabilities that we have here could developed at other facilities, but combined with our people, I think the ability to do the hazardous testing out here in a remote location safely is what sets us apart from the other NASA facilities. And honestly, these capabilities are really interrelated with each other. And so it would be difficult to do, let’s say for example, hypergolic engine testing if you didn’t have the propellant chemistry capability located nearby as well.

Host: Do additional aspects of WSTF’s capabilities come to mind that might be useful to NASA program and project managers?

Cort: I think there are some unique things that come to mind, at least for me. I think we’re a little bit unique in the agency that we’re not directly funded by the programs. Which isn’t to say that the programs don’t have to pay for the testing that they need, but they don’t really pay to own or maintain the capabilities. They pay the cost to set up, do their test, get their test results, and then that capability is there for them again when they need it in the future, even though they don’t have to pay to maintain it throughout that quiescent period. I think we’ve successfully shown time and time again that we’re able to provide a valuable test capability for the programs. They get a result and a value for their money that they can’t get elsewhere.

Host: Are there specific success stories that you’d like to share with us?

Cort: Well, Deana, I think I could go on all day about some successes that we’ve had. I’ll try to keep it to some that are either relatively recent or that I personally had a hand in. Maybe the most recent ones that I can think of right off the top of my head are really related to the agency’s desire to partner with commercial providers and be able to provide spaceflight services commercially.

So, in 2016, remember the SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket had a serious accident while sitting on the launch pad during a preflight test. Now this one was not a NASA mission. However, the next NASA mission to fly on a Falcon 9 rocket was going to be the Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite, or TESS, and the people who were responsible for that satellite wanted to make sure that they understood the cause of the failure before they put their asset at risk.

And so, as a result WSTF developed a full-scale ground test capability to test a composite overwrapped pressure vessel submerged in liquid oxygen in order to understand the cause of that Falcon 9 failure. This was a unique test for us because it really cross-utilized some of our current capabilities, that being of the composite overwrapped pressure systems and the oxygen material compatibility, and successfully led not only to the launch of TESS, but ultimately to the ability to launch crew on the SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket. Most recently, Bob Behnken and Doug Hurley successfully returned from the ISS on a spacecraft built by SpaceX.

Another example is also related to SpaceX. Remember a year or so ago, maybe slightly more than a year ago or so, during a ground test on the Dragon spacecraft, a failure occurred that caused the loss of that spacecraft, WSTF was involved in developing some unique test capabilities to understand the nature of that failure and evaluate the fixes proposed and implemented by SpaceX.

Again, because the nature of the failure involved material compatibility and energetic fluids and the presence of multiple unique capabilities here at White Sands, the hypergolic propellant capability and the flammability of materials and oxygen, were invaluable to the ultimate success of that test effort.

Deana, just to make sure I’m not really picking on SpaceX, I want to mention that WSTF was also involved in some testing for the Boeing Commercial Crew Program. Specifically, the CST-100 launch abort system. During a test here at White Sands, there was a failure in some of the hardware that was provided by Boeing as part of their spacecraft and we were heavily involved in the failure analysis and the refurbishment and rebuilding of that test article, ultimately leading in a successful test that will help certify their vehicle after they get ready to fly.

One more example, which is near and dear to my heart. So it goes back a little bit further, but if you remember the Cassini mission to Saturn, we at White Sands were testing the main engine assembly whose primary purpose was to do the orbit insertion burn once the vehicle arrived at Saturn. And during the testing, we discovered a dynamic interaction between the combustion in the rocket engine and the propellant feed system that could have resulted in failure of the spacecraft if it didn’t get detected during ground test.

So, from that test discovery, it turned into, ‘Well, what do we do about this for the spacecraft that’s expected to launch less than six months from now?’ And WSTF, along with the Jet Propulsion Laboratory and Lockheed Martin, who was the provider of the spacecraft, developed a number of fixes that could potentially be utilized. And we tested each of those fixes before ultimately settling on a final fix that could be implemented prior to launch and also tested the envelope that the vehicle might fly in to determine if there were some changes to that envelope that would ensure safety of the mission.

Host: And White Sands was very instrumental in the Space Shuttle Program as well, right?

Cort: Absolutely. I didn’t mention this before, but following the completion of the Apollo Program, at White Sands Test Facility we came very close to being closed down while they developed the Space Shuttle Program. But fortunately for us, the orbital maneuvering system and the reaction control systems in the space shuttle orbiter used the hypergolic propellants where a lot of the expertise at White Sands lived. And so that turned into a very involved testing program for those systems on the space shuttle orbiter.

All throughout the Space Shuttle Program, we were engaged in a myriad of testing using all of the core capabilities at White Sands, even though at the time we didn’t really call them our core capabilities. Interestingly enough, what most people don’t realize is that WSTF was also responsible for maintaining and operating the White Sands Space Harbor, what we call WSSH, or W-S-S-H. And WSSH was an alternate landing facility for the space shuttle program. Even though only STS-3 landed there in 1982, something like 85 perecent of the approach and landing training flights that the astronauts did prior to flying the space shuttle were performed over at WSSH.

And the reason so many of the training flights were done at WSSH was twofold. One is that we’re a little bit closer to the Johnson Space Center, which is the home of the astronauts, but also the runways were built at the White Sands Space Harbor to simulate the runways at the Kennedy Space Center, at Edwards Air Force Base, and also the European and African contingency landing sites were all available in one location. So, if they wanted to train for a contingency landing overseas, they could come out here to White Sands, train that on one approach, and then they could turn around and train on a KSC runway on the next approach and so on and so forth.

So, really interesting. We’ve retired the White Sands Space Harbor at the end of the shuttle program. However, Boeing, working with the White Sands Missile Range, which is an Army facility, is planning to use the White Sands Space Harbor or the general area of the White Sands Space Harbor for landing their Commercial Crew Program CST-100.

Host: Could you describe some of the other fascinating work that’s performed at White Sands?

Cort: Couple of other things that come to mind: In the late 1980s or so, the engineers in our oxygen group were heavily involved in developing standards for medical oxygen regulators that are used throughout hospitals, and even the regulators that your grandma or grandpa might have if they’re on oxygen at home.

This all developed out of a series of fires that occurred in oxygen medical regulators because of a change in materials that the manufacturers did, and they didn’t really understand the implications of that material change. And the engineers at White Sands not only helped them solve the problem of those fires, but also develop standards that are still in use today that oxygen medical regulators have to be tested to. Now, we don’t own those standards — those belong to a different organization — but we helped to develop them.

Some other really unique things that we’ve done over the years. A few years ago, we managed a project that intentionally dropped a solid rocket motor out of a helicopter to evaluate whether or not it would explode on impact. This was part of a Department of Defense program that was necessary for them to help understand what would happen in the event of a launch failure.

Similarly, we have a drop tower out here that allowed us to drop up to a metric ton of propellants in order to evaluate the potential risk of a blast over pressure on the launch pad or on launch pad control centers if you had a fallback of a rocket during a launch.

Host: So, that’s really interesting, Bob, but I don’t think you mentioned UFOs or aliens or Area 51.

Cort: Well, Deana, I’m not really supposed to say where we have the aliens hidden.

Host: Not even for our podcast?

Cort: Not even for a podcast. No. In all seriousness, most of that alien activity is over closer to Roswell, New Mexico, which isn’t really too terribly close to us. Although we do occasionally get questions about it. And honestly, I think it’s fun to joke about it. But in my opinion, there really isn’t much to it. Not to say that I don’t believe that life isn’t out there somewhere, I just don’t really believe that it crashed and landed near Roswell, New Mexico.

Host: On a more serious note. What are some of the challenges you face?

Cort: I think we face some of the same challenges faced by other NASA facilities, and that is, is there enough budget to do the work that we need to do? And is there enough budget to maintain aging infrastructure?

I mentioned earlier that the facility, most of the facilities that we have here, were built back in the 1960s and some of them that have exceeded their useful life. So, we’re always in a constant struggle to make sure that we’ve got the funding and the facilities to do the testing that we needed. And then related to that, since we are primarily funded by the programs only on an as-needed basis, in other words, they fund us for the work that we’re doing right then in the moment, making sure that we maintain those capabilities between the needs of the test programs is really critical. We’ve been really successful so far in just making sure that we move from one program smoothly to the next program. But I do worry about in the future if we’ll be able to maintain that capability or those capabilities as we go forward.

Host: When we think about going forward, does WSTF have a role in NASA’s human missions to the Moon and Mars?

Cort: Absolutely without a doubt. WSTF was built to provide testing for man’s first foray to the Moon and I really believe that we’re going to be a vital part in man and woman’s next foray to the Moon. And obviously the Moon, if it’s a steppingstone to Mars, then we’ll still be engaged when we go onto Mars. We’re really engaged already in testing for the next lunar program, which will turn into a Mars program.

And that is we’re doing propulsion testing for the Orion spacecraft, we’re doing materials testing for the Space Launch System, the SLS, and we’re starting to do early materials testing and hazard assessment for the Gateway. So, there is no doubt in my mind that we’ll be engaged in human spaceflight for the destination Moon and for the destination Mars for the long haul.

Host: Bob, thank you so much for joining us. I’ve really enjoyed getting to learn more about White Sands.

Cort: Deana, it’s been really a pleasure talking to you. I’ve got lots more stories if you’ve got more time for them.

Host: We’d love to hear more.

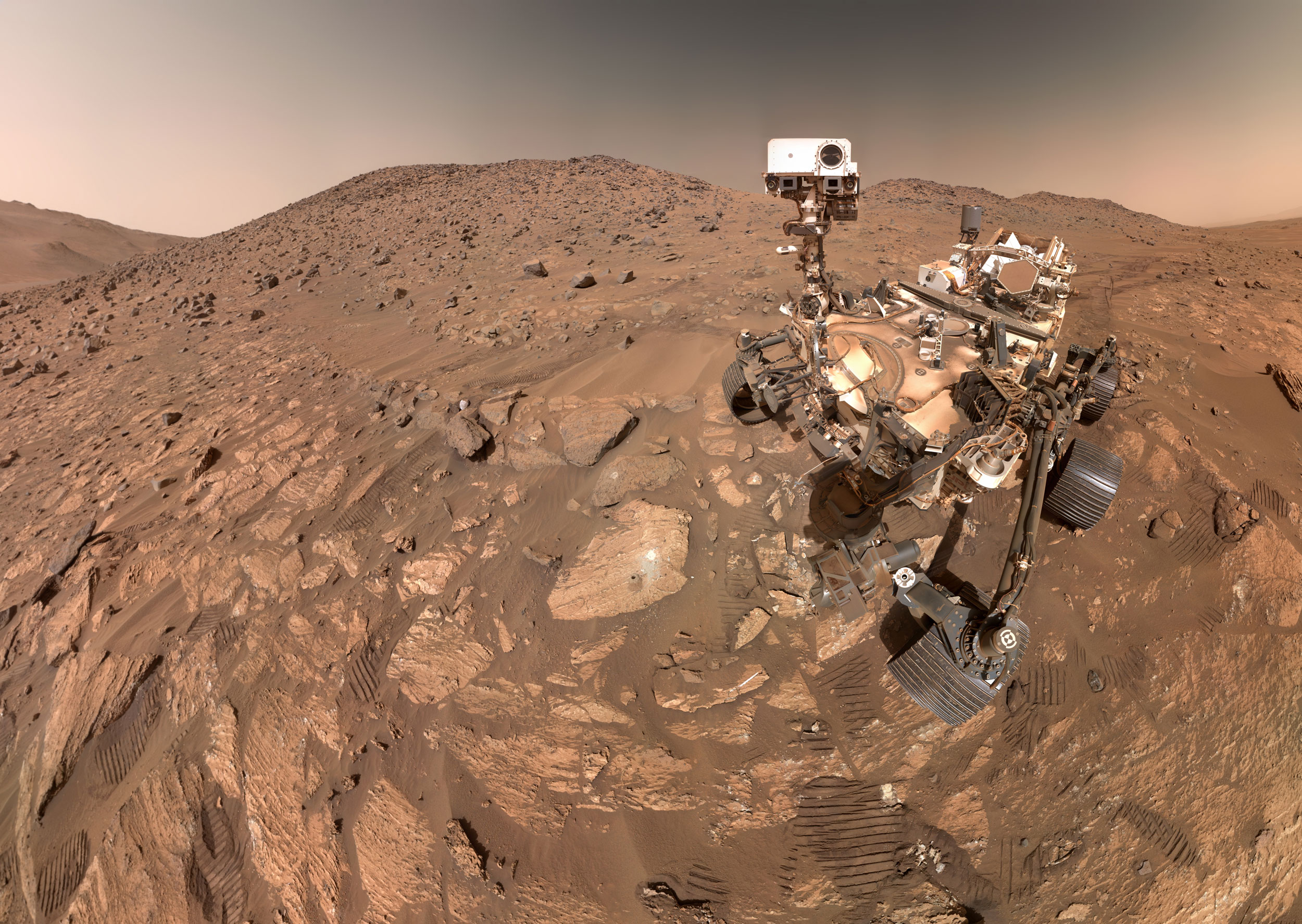

Cort: Well, Deana earlier you asked about some of the unique testing that we’ve done out here. Years ago we actually put simulated Martian soil in the bottom of one of our test stands in order to evaluate whether the rocket exhaust, when you landed on Mars, would possibly show up as life when you sample that Martian soil nearby where you landed. It’s actually turned into development of a reformulated version of hydrazine propellant that’s still in use today.

We also house some of the Moon rocks here at the White Sands Test Facility as a contingency site, in case of a hurricane or other natural disaster in the Houston area. That way we don’t lose all of those samples in one fell swoop if something like that were to happen.

And I really expect that when we bring more samples back from the Moon, samples back from asteroids, and samples back from Mars, that we will house some of those here in order to make sure that we protect them from potential natural or unnatural disasters.

Host: Links to topics discussed during our conversation are available at APPEL.NASA.gov/podcast along with Bob’s bio and a show transcript.

If you haven’t already, we invite you to take a moment and subscribe to the podcast and tell your friends and colleagues about it.

As always, thanks for listening to Small Steps, Giant Leaps.