Andres Almeida (Host): Welcome to Small Steps, Giant Leaps, the podcast from NASA’s Academy of Program/Project and Engineering Leadership, or APPEL. In each episode, we explore the experiences and lessons learned of NASA’s technical workforce. I’m your host, Andres Almeida.

Today we’re diving into a topic that’s both fascinating and vital to the future of our planet: planetary defense.

Protecting Earth from potentially hazardous asteroids and comic impacts is an ongoing mission. At NASA, the organization at the heart of this effort is the Planetary Defense Coordination Office, or PDCO. It was established to detect, track, and, if necessary, help mitigate the threat of near-Earth objects. The PDCO plays a critical role in ensuring our planet’s safety from cosmic hazards. Joining us today is Dr. Kelly Fast, acting planetary defense officer, and NASA’s Near-Earth Observations Program manager.

Hey Kelly, thanks for being here.

Kelly Fast: Oh, thank you for having me.

Host: Can you start by explaining your role in the Planetary Defense Coordination Office?

Fast: Right now, I am the acting planetary defense officer, and the planetary defense officer leads the Planetary Defense Coordination Office, and essentially has the leadership role in planetary defense activities across NASA that fall under the Planetary Defense Coordination Office, and also in coordination with other parts of NASA in implementing NASA’s planetary defense mission.

I’m also the Near-Earth Object Observations Program manager, and that program addresses kind of all of the non-spacecraft mission activities, pretty much for planetary defense, all of the finding the asteroids, the observatories that do that, that follow them up and confirm discoveries that study their physical properties, the data centers that help support all of that, like the Minor Planet Center and the Center for Near-Earth Object Studies, our mitigation research activities, and other activities, again, to, to advance that mission of, you know, finding asteroids before they find us, and they maybe research toward getting them before they get us.

Host: So how does NASA track Near-Earth Objects?

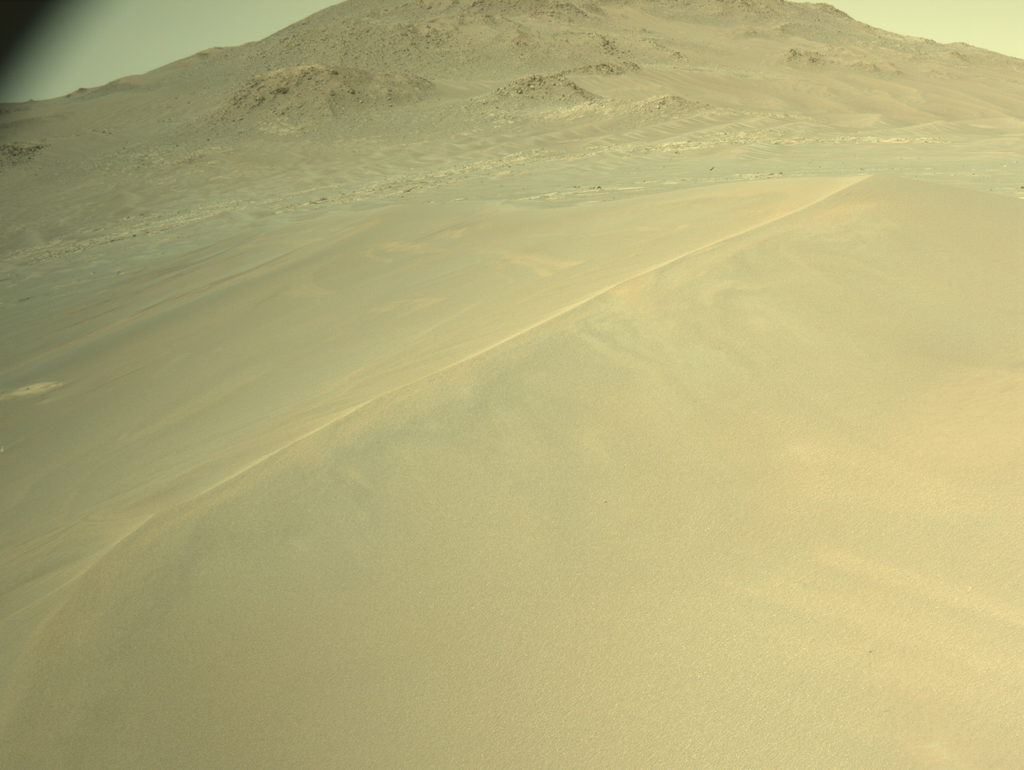

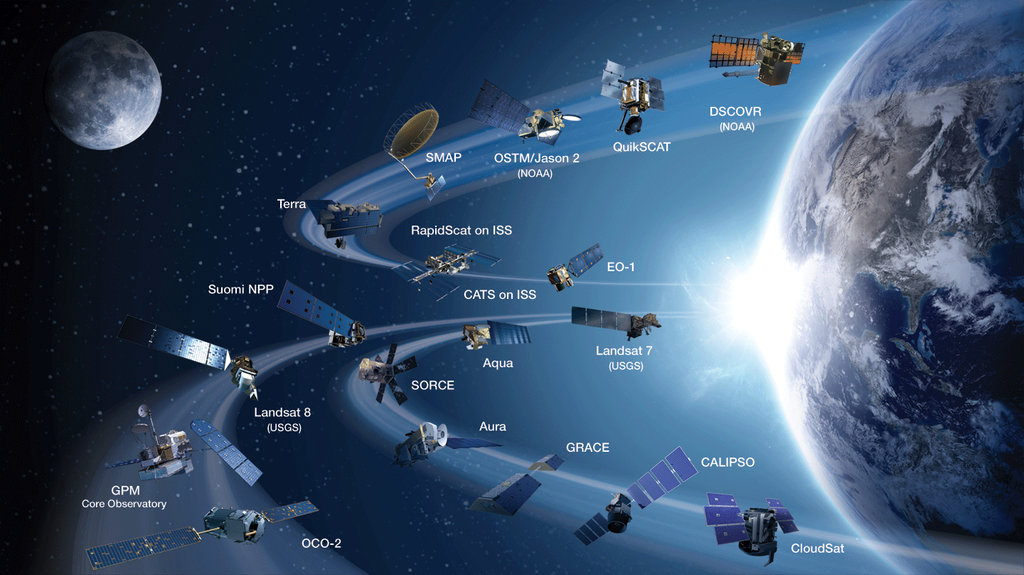

Fast: Well, I always say that, kind of the fundamental first priority of planetary defense is finding the asteroids. We can do all sorts of other research, but we have to find them first. We have to know where they’re going to be in the future. And so there are telescopes that survey the skies every night, looking for near-Earth asteroids. You talk of some of the NASA telescopes, like James Webb Space Telescope, that’s like really zeroing in on particular targets in the sky. Here, we’re talking about telescopes that survey wide swaths of the sky, looking for moving objects. It sees the stars, and you see these points of light moving against the stars, and maybe those are asteroids we already know about. Maybe they’re new asteroid discoveries. Maybe they’re satellites in orbit around Earth that we need to identify and not include.

So that’s kind of the first part: Telescopes that survey the skies. There are other telescopes funded by NASA that do follow-up to get additional observations, because it doesn’t help to see an asteroid if you don’t get enough observations to predict where it’s going to be in the future. And the big part of that are the data centers. The Minor Planet Center (which is also funded by NASA), which is the internationally recognized repository for position measurements of small bodies from NASA-funded telescopes or telescopes around the world. They receive that information and determine is something a new discovery? Or are these additional observations and whatnot?

And then the Center for Near-Earth Objects Studies at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, they take those measurements from the Minor Planet Center, and they do precision orbit determination, way out into the future, to determine if something poses a long-term impact threat to the earth, or even in the short term, something that maybe hasn’t even been confirmed yet. Does this pose a short-term impact threat?

Host: So, it’s not just a NASA thing, what you’ve mentioned. This is an international collaboration as well?

Fast: Right. NASA does have a leading role, given that, you know, NASA’s been doing this work since the late 90s, formally doing Near-Earth Object research and then formalizing it under the Planetary Defense Coordination Office in 2016. But there have also been observatories around the world involved in searching for small bodies and near-Earth asteroids or studying them. And so there, there does exist, you know, in addition to just the collaborations that already exist out there, there is an International Asteroid Warning Network, which is a collaboration of space agencies and observatories and universities and institutes actually doing this kind of work as a way to make sure that we can share information and actually be able to share that information in the event of an identified threat.

That is actually something that was recommended by the United Nations to have such a group as part of their studies of the impact hazard. And so, it isn’t just the U.S. doing it. Our colleagues at ESA and and then also observatories from many countries around the world involved in this, whether or not they’re a part of the International Asteroid Warning Network, but right now, the International Asteroid Warning Network has, I think it’s 60 signatories from 25 countries, so, and growing.

Host: Going back to near-Earth objects, or NEOs, what makes tracking them or detecting them so challenging?

Fast: Yeah, tracking near-Earth Objects and just finding them in the first place, it’s challenging because, you know, it’s easier to find the big stuff, the bright stuff, and so over the years, the larger objects, there are fewer of them, and they’re easier to find, like the multi kilometer-sized asteroids. That that population is pretty well, well known because it’s brighter and and the as you go, fainter as you go to smaller asteroids, they can be tougher to find, depending on the capabilities that you have. How faint can you go with your telescopes? And of course, the earth is going around the Sun, and the asteroids are going around the Sun. Sometimes you have to wait for things to come around to be able to find them. You can’t find them all at once. And as you’re looking for smaller and smaller asteroids, it can make it more challenging.

Now, the good news is, the earth’s atmosphere is pretty good at protecting us. So, these really small asteroids, a couple of meters in size, they just make pretty fireballs in the atmosphere. And as I said, the really large ones, multi-kilometer size, asteroids – that population seems to have been found because maybe only a couple of new ones are found every year that models and such indicate that, yeah, that one’s pretty well in hand. It’s kind of the in-between the asteroids that could make it to the ground intact and could do damage, trying to find that population. So, and that’s something that actually, Congress has tasked NASA with doing, is finding the 140-meter and larger asteroid population.

We want to find ones of any size and even smaller ones can, you know, can do damage, but you got to set a metric somewhere, and that’s, that’s a size that could still do regional damage should it impact. And that’s why NASA has been trying to find ways to speed up finding asteroids, so that you don’t have to wait for decades with our current capabilities.

And so in particular, the Near-Earth Object Surveyor mission is something that NASA is developing to address that issue of finding and because they can be faint and if you have to wait for them to come closer, but looking in the infrared is a way to advance that too.

Host: Especially if they come from the direction of the Sun. Is that right?

Fast: Right? Well, we’re it’s true, because you’re talking about like, the Chelyabinsk asteroid.

Host: Yes!

Fast: That came from the daytime sky, and the telescopes on the ground are looking at the nighttime sky. And really, we’re looking at objects that are on orbits that you could catch them at many times, and many points of their orbits might not be during the day. If they pass into the nighttime sky, then we can pick them up, get them up, get them cataloged to know where they’re going to be in the future. But if it’s at that first time that we’re catching it and we don’t now, that was something that was very small, but it was coming from the daytime sky. And one thing that the Near-Earth Object Surveyor mission will be able to do from its vantage point in space is to point closer to the direction of the Sun, which will be helpful on that front.

But also going after the population of asteroids that maybe are harder to find from the ground, both because of maybe the orbits are on their location, but also the coloring of their surfaces, because the telescopes on the ground are looking at reflected light, and asteroids are already pretty dark, but some are even darker than others, and if they’re not reflecting a lot of light. Going into the infrared, going into space, and going into the infrared is a way to get around that, but it will also be something very important, in concert with the telescopes on the ground that are looking at opposition, looking at the nighttime sky away from the Sun.

And then Near-Earth Object Surveyor is going to be looking along Earth’s orbit closer to the direction of the Sun. So that kind of gives to find the asteroids that pose the greatest hazard to Earth. But it ends up being very complementary to be able to catch asteroids at different parts of their orbits.

Host: So we had the world’s first test of planetary defense technology when the DART mission successfully changed the orbital period of a small it was a non-hazardous asteroid, yeah, Dimorphos. What have we learned so far?

Fast: Well, that was very exciting. Because, I mean, as I said, the most important thing is finding the asteroids. But if you did find something that posed a threat, you’d like to have some capabilities to maybe do something about it that you’ve actually tested. And so this, this is a huge milestone. You know, it’s one thing to have physics and say, “Okay, here’s a spacecraft of a certain mass and an asteroid of a certain size, and we predict maybe we could deflect it this much,” but to actually try it out on an asteroid with real physical properties – so, a lot was learned there.

One of the main things that was the goal of the mission was to understand beta, essentially, that enhancement factor, because, as you saw from images of the DART impact, even before impact, that asteroid was a pretty rubbly-looking asteroid. It wasn’t just a solid, monolithic object with nothing on the surface. And so when DART impacted, there was this plume of material that was released. And this was expected. It was just a question of how much might there be and what the effect would be.

And that’s what was measured, kind of that extra “oomph,” that extra push that was given to the asteroid because of that material being thrown off of the surface and that enhancement factor, and so. learning about that was very important and a key part of the mission, but some of the kind of “a-ha’s” were also, and we’ve seen this with other with other missions, is that there are a lot of asteroids out there that are very rubbly rubble piles, and kinetic impactor is one way to perhaps deflect an asteroid. But could it possibly disrupt an asteroid depending on its size and its makeup? And so, so that kind of is something that caused us to step back and say, “Okay, this is one technique of deflection, and we’ve learned a lot about it. But it’s kind of teaching us maybe what we need to continue learning about.”

And it’s also reminded us, as we’ve always known, for any scenario, it will depend on the asteroid. We’ve seen many other asteroids from other NASA missions, and how you how you might deflect the asteroid could very well depend on its physical properties. And so DART has maybe also taught us that, you know, really it was, it was cool to see that asteroid in those last few seconds before impact. But can you imagine if there had been the time to go study it ahead of time and then really plan, you know, a deflection based on those physical properties, so…

Host: Perhaps, even get a sample!

Fast: Yeah, yeah, right!

Host: Earlier this year, in 2024, NASA participated in this biennial exercise, the Planetary Defense Interagency Tabletop Exercise, which was an opportunity for NASA and other agencies and the government to sort of coordinate a response correct or understand what would need to happen should a threat be identified? What are some key takeaways and recommendations from that exercise?

Fast: Right. And asteroid impact is something highly unlikely, but if we ever were to face that, it would be good that it wasn’t the first time that, you know, the government, across the government, started, you know, thinking about such a scenario. And so for a number of years, NASA and FEMA have had meetings and had some exercises and , and they’ve expanded to these larger interagency tabletop exercises to walk through a particular asteroid impact scenario. This most recent one, it was 14 years in the future is where this impact could happen, which was different from the previous scenario, which was a short warning, where you might not have mission options. And so, this was a case where there were mission options, but there were decisions to be made, too.

And so as part of having participation by agencies across the government, it was a good chance, first of all, to orient them to this particular threat scenario and and just the activities that feed the information, such as the activities at NASA, to walk through that in general, but then specifically, like to learn about what do they need to know to make decisions on their side, and at what point do they act in their roles?

Like, for instance, you know, FEMA, they do emergency response. NASA doesn’t do emergency response. We and even though, in the movies, sometimes there’s like one scientist out there making it all up as they go, and an expert on everything, I mean, there are different roles across different agencies, and so it’s a good chance to really learn from each other. You know what the different roles are. It’s also outlined in a national strategy, which is very important. There’s a White House National Strategy for Planetary Defense, defining the roles of different agencies in such a situation and also just in developing planetary defense capability, but to have those discussions about what what we knew at that time in the scenario, and what we didn’t know, and what actions different agencies might take.

Because, you know, they like, for instance, FEMA will already have all kinds of other things to deal with. And so it’s not like everything would get dropped for an asteroid 14 years in the future, they’re dealing with, like a hurricane right now, for instance. Learning about some of our DOD colleagues that, you know, again, in the movies, they’ve got the lead on it. Well, actually, they were talking about how, you know, they have a support role here, because this is something it has the lead on. And so learning that was very valuable, and also kind of what we needed to know, again, the idea of maybe the capability to send missions, to get more information, to enhance what you can get from the ground (especially since there are times when you can’t see an asteroid from the ground), to be able to convey information, communication, to be able to make decisions. What’s the information for decision-making and, again, the roles across the government, but also internationally, because we don’t operate in a vacuum.

Host: Yeah, you’d want to do knowledge sharing.

Fast: Yeah, the knowledge sharing across organizations within NASA, outside of NASA and also internationally. This was the first exercise where we had representation from our international colleagues. We had from the UN Office of Outer Space Affairs, which is highly involved in the International Asteroid Warning Network that I mentioned earlier, and the space mission planning advisory group, another recommended collaboration, recommended by the UN, that’s the collaboration of the world space agencies to be able to recommend mission options. I mean, countries make decisions about how they’re going to proceed, but to have an international collaboration, getting together, sharing information and making some recommendations, to consider learning about how same page, as we call it, functions, was very valuable here. And input perspective from our UN colleagues, from our ESA colleagues, especially since they have a planetary defense office also. There’s a lot of coordination there from representatives from a few other international space agencies. Again, just realizing that we don’t, we don’t function in a vacuum, and an asteroid impact is something that does affect the whole world, no matter what part of the world might face it.

Host: So, are there ways for the public to get involved with near-Earth Objects, tracking?

Fast: Yeah. So, the the public, you know, it is. It is something that, you know, large telescopes. It’s hard to compete with large telescopes, you know, with being able to go out and find asteroids. But But there are citizen science activities that NASA supports through our program, and then, of course, there’s a number of citizen science activities across the different sciences but, but there are a couple that allow people to go in and look at images of the sky and look for moving objects that maybe got missed. There are things that the human eye can pick out that that software and a first check maybe can miss. And so that’s been very valuable, mainly for identifying some main belt asteroids, you know, out between Mars and Jupiter that might have fallen through the cracks. Because that’s helpful for later to be able to rule them out in future survey work, so certainly citizen science activities, but also just awareness communication.

There’s an initiative that hasn’t been voted yet, but there’s an initiative for an International Year of Planetary Defense, a U.N.-sanctioned international year, and which has been proposed, to have like that year of asteroid awareness and planetary defense in 2029. That’s when the asteroid Apophis is going to pass very close to Earth. It’s not going to impact Earth. We know enough about it that it’s even been kicked off the risk list, but it’s very unusual. We get buzzed all the time by small stuff, but this is a, like, a 340-meter asteroid. That’s a large asteroid to pass so close to the earth, but it’s a chance to raise awareness.

Host: What an opportunity.

Fast: Yeah! So, the public can get involved there in education activities and and that’s just going to be a fun chance to learn more as activities. You know, whether or not there’s an international year, things are going to spin up around the time Apophis goes by. But we hear there’s a lot of support for an international year. And so, like with the International Year of Astronomy, there’s probably gonna be a lot of activities around that too, for the public to get involved.

Host: Looking forward to that. And we’ll put this in our resource list, but there are no known threats for the next 100 years that we know based on data, correct?

Fast: Right, for what we do know. You know, again, the folks at the Center for Near-Earth Object Studies at JPL, they’ve calculated way out into the future and there, there is a risk list, but anything on there has, like, such a low probability of impact way out in the future that there’s just, there’s just nothing that poses a risk that gets elevated, you know, to a level. Every so often something will pop up, and the more observations you get, then it gets downgraded or kicked off the list. So that’s a really good thing to know. Every so often we’ve had these. We had one earlier this year, one of these short warning impactors, where it’s only been like nine times that an asteroid has been observed in space prior to impact, but we’re talking about the small stuff. It makes a pretty fireball. Our atmosphere takes care of it, which is great. And they’re only discovered at the last minute, because you don’t see until they’re really close, because they’re tiny, and they don’t pose a threat anyway. But there is, there’s nothing on the risk list that does pose a threat.

It’s what we don’t know about that we’re concerned about, and that’s why we keep looking that’s important.

Host: It’s important work. So Kelly, what was your giant leap?

Fast: That’s an interesting question, because I feel like in my career, I’ve had more of a slow crawl, of a giant leap.

Host: Small steps!

Fast: Small steps, yeah, really! I always joke that no kid ever says I want to work at NASA Headquarters when I grow up. But I knew I wanted to be an astronomer, and so I just kind of went that route with my education and everything, but maybe not really knowing what it meant. So I think those small steps that maybe led to the giant leap to planetary defense, I would say, are just all the people along the way who maybe nudged me or advised me or pushed me, or said, why don’t you do this?

Or, you know, there was, I actually had a gap in my schooling where I had stopped at a master’s and I was working and having kids and all that, and then they kicked me back into grad school. But I’m grateful for those who kind of pushed me in that way, and then later being asked to come to NASA Headquarters to help run programs. And then even I joke that then I woke up one day and I was running the Near-Earth Object Observations Program. But you can make a plan for that giant leap, but often it won’t play out that way. And I guess for me, when the pathway was meandering, I would almost, that would be very disturbing, but I’m now realizing, you know, that’s actually a really good thing.

And so, I guess all those little, small steps that add up to the giant leap, I am very grateful to people along the way who’ve kind of nudged me so that it happened. And I’m very grateful to find myself here doing an amazing mission, being involved in planetary defense and the Planetary Defense Coordination Office.

Host: That’s wonderful. And I can’t let you go without mentioning you even have an asteroid named after yourself. Did that ever cross your mind that that would happen in your journey?

Fast: No, certainly didn’t. I’m very honored. I mean, it’s a wonderful honor. Maybe not as amazing as it might sound, because there are a lot of asteroids out there, but this particular one was discovered by a colleague, and so to have one that was actually discovered by someone I know, and to be honored in that way, I’m very grateful for that. So it’s a wonderful thing, then to be able to say, “Yes, I have an asteroid!” and but I feel like, in a way, I’m earning it now by working in planetary defense.

Host: Wonderful. Thanks for all you do, for your team, for all they do. Thank you for being here, Kelly.

Fast: Thanks for having me.

Host: That’s it for this episode of Small steps, Giant Leaps. For more on Kellyand the topics discussed today, visit our resource page at appel.nasa.gov. That’s A-P-P-E-L dot NASA dot gov. And don’t forget to check our other podcasts like “Houston, We Have a Podcast” and “Curious Universe.”