“Houston We Have a Podcast” is the official podcast of the NASA Johnson Space Center, the home of human spaceflight, stationed in Houston, Texas. We bring space right to you! On this podcast, you’ll learn from some of the brightest minds of America’s space agency as they discuss topics in engineering, science, technology and more. You’ll hear firsthand from astronauts what it’s like to launch atop a rocket, live in space and re-enter the Earth’s atmosphere. And you’ll listen in to the more human side of space as our guests tell stories of behind-the-scenes moments never heard before.

Episode 29 features Patrick O’Neill, Marketing and Communications Manager at the Center for Advancement of Science in Space (CASIS), who talks about the part of the International Space Station designated as a U.S. National Laboratory, what that means, and how CASIS manages research from all over the world that could ultimately benefit humankind. This episode was recorded on January 19, 2018.

Transcript

[00:00:00]

Gary Jordan (Host): Houston We Have a Podcast. Welcome to the official podcast of the NASA Johnson Space Center, Episode 29, The National Lab in Space. I’m Gary Jordan, and I’ll be your host today. So this is the podcast where we bring in the experts, NASA scientists, engineers, astronauts, sometimes some of our partners. We bring them right here on the show to tell you all the cool stuff about what’s going on here at NASA. So today we’re talking about the section of the International Space Station that’s designated as a U.S. national laboratory. We’re talking with Patrick O’Neill, the marketing and communications manager at the Center for Advancement of Science in Space, or CASIS. We had a great discussion about what it means to be a U.S. national lab, how CASIS is bringing research from companies, research to institutions, and government agencies to the Space Station, and the things we’re learning that benefit human kind. So with no further delay, let’s go light speed and jump right ahead to our talk with Mr. Patrick O’Neill. Enjoy.

[00:00:53]

[ Music ]

Host:All right, well, Patrick, thanks so much for taking the time to come on the podcast, especially because you are remote, right? You’re not even here in Houston. You’re calling in from Florida, right?

[00:01:26]

Patrick O’Neill: I am over at Kenney Space Center as we speak.

[00:01:29]

Host:Awesome. And that’s where CASIS is sort of housed? Is that where you guys are? Or are you kind of all over the place?

[00:01:36]

Patrick O’Neill: Well, we actually have a couple of houses across the country. But yes, in theory, this is kind of where our headquarters is based out of in the Kenney Space Center area, as well as Melbourne, Florida. But we also have strong office presence just outside of Johnson Space Center in Houston, and then we have a few more offices that are sporadically placed throughout the country.

[00:01:54]

Host:Very cool. All right, so you’re over at the Kenney Space Center, yeah, Kennedy Space Center right now. So how’s the weather over there?

[00:02:00]

Patrick O’Neill: The weather right now is, it’s a tad cold. We had a little cold front come through. So it’s nowhere near as bad as it is in places like the northeast, but, you know, we actually had to turn the heat on, and that’s something that is a rare occurrence here down in Florida.

[00:02:12]

Host:Yeah, you know, I mean, over here, the weather has just been absolutely crazy. I’m sure you’ve been paying attention. But this past week, I mean, we had like ice and freezing rain and all the roads were covered in ice, and Houston just doesn’t have the infrastructure to deal with that. So we just, you know, the center shut down. The south can’t really deal with that stuff. And right now, it’s freezing right now. I mean, we’re in the studio, and the studio is always cold, but it’s like, you know, 30s right now, which is, I’m sure the people in the north are thinking, man, that guy is definitely a baby when it comes to the cold. But, you know, when you’re used to 60s and 70s in the winter, this can definitely, this can definitely get to you.

[00:02:48]

Patrick O’Neill: Well, you know, being in Florida right now, it’s 55 when I hopped out of my car, and everyone is bundled up as though, you know, it’s 15 outside. So, you know, I think that we are certainly living in First World problems as well.

[00:03:00]

Host:I’ve seen that before. I’ve been to– it was an air show out at Ellington Field one time, and it was, it was low 60s and not a cloud in the sky. Absolutely crystal clear day. And I was wearing shorts and a T-shirt because the Sun was beating, and I thought it was a hot day, especially on the tarmac, but you had folks that were bundled up as if it was a cold winter day, and I could not believe it. Low 60s, and they were bundled up. It was crazy.

[00:03:25]

Patrick O’Neill: Can’t take them anywhere.

[00:03:26]

Host:Okay, but we’re not connecting, you know, from across, from Houston to Kennedy to talk about the weather. We’re here to talk about the U.S. National Laboratory. And you being the marketing and communications manager of CASIS have a pretty good understanding of just CASIS as a whole. So why don’t we just talk about that, you know, what is, what is CASIS?

[00:03:49]

Patrick O’Neill: Yeah, sure, so first and foremost, CASIS stands for the Center for the Advancement of Science in Space. Since we are kind of a brainchild of NASA, and since NASA equally likes to work in the world of acronyms, we decided to go out there and call ourselves CASIS.

[00:04:01]

Host:Good call.

[00:04:02]

Patrick O’Neill: And so in 2011, we were tasked with managing the U.S. National Laboratory aboard the International Space Station.

[00:04:08]

Host:Okay, and so that means what? Managing– what is the U.S. National Laboratory?

[00:04:14]

Patrick O’Neill: What is it that you say you do here, yeah. So when I say that we manage the U.S. National Lab on the International Space Station, that means that we get to select, broker, manifest, and then promote the research that goes on the U.S. National Lab portion of the flight manifest. And so what do I mean by flight manifest is on a given resupply mission to send research and supplies to the station, there will be up to 50% of that research allocation that is designated as U.S. National Laboratory based research. And so we get that 50%. So we pick and choose the research that goes up. And within my role, I get to work alongside you and other folks at NASA to help communicate the benefits of the research that is going to the Space Station.

[00:04:57]

Host:Okay, I see. So the U.S. National Lab is a NASA thing. And then CASIS is the, you know, is the industry that manages it, I guess.

[00:05:06]

Patrick O’Neill: I would say that the U.S. National Laboratory is a U.S. thing.

[00:05:10]

Host:U.S. thing, I see.

[00:05:11]

Patrick O’Neill: And so a little bit of background on how the Space Station ended up becoming a National Laboratory. In 2005, Congress, in their infinite wisdom, they were looking at all the research that was happening on the Space Station, and, you know, it was catered towards NASA’s exploratory endeavors, living and working in space, better understanding the human condition, so that you can do long duration space flight or go beyond low Earth orbit. And they said, that’s terrific, and we’re learning so much, but there’s also so much more that we could be doing on this Space Station. What if we were to open it up to all sectors of the research community, whether that’s Fortune 500 companies, or innovative startups, academic researchers, student investigators. I mean, there’s so much that we could do on this Space Station. So what if we turn it into a National Laboratory and really kind of see what this thing is capable of from a research perspective, and see if we can’t use the microgravity environment to benefit life on Earth. So in 2005, that’s kind of how we got this, the concept of a National Laboratory. And then in 2010, I want to say, Congress worked with NASA saying, you know, we need to have a non-NASA entity, a non-profit organization manage the research on this U.S. National Laboratory.

[00:06:25]

And so in 2011, CASIS was selected by NASA to manage the National Laboratory, and we have been assuming management of the National Lab since that timeframe.

[00:06:35]

Host:There you go. Okay, so what was originally a laboratory for NASA, to do NASA research, now is opened up to– is it anyone or is it just people in the U.S.?

[00:06:47]

Patrick O’Neill: So, and that’s a great question. It is open, in theory, to anyone. However, you have to have U.S. subsidiaries or U.S. interests involved. So, I mean, there’s a various of companies that we work with that might have headquarters overseas. But, you know, if it’s a pharmaceutical company, I’ll give you an example. Like Merck Pharmaceuticals, I believe that they’re based, in theory, overseas, but they have such a large footprint here in the United States, and so we work with investigators that are based here in the U.S.

[00:07:15]

Host:I see. Okay, but then they can use, you know, they can go through CASIS. CASIS will manage getting whatever research that they want to do up on the International Space Station because it will eventually benefit the, you know, U.S. citizens.

[00:07:30]

Patrick O’Neill: Right, and what I would say, the caveat, again, is that the research that we manifest and broker and send to the Space Station and then send back down to the Space Station, in some cases, again, the caveat always has to be that there has to be a tangible benefit for life here on Earth as opposed to, again, NASA is much more focused on exploratory research endeavors.

[00:07:50]

Host:How about that? Okay, and you said 50%. That’s a decent amount of research.

[00:07:54]

Patrick O’Neill: That’s a pretty good chunk of change, right?

[00:07:56]

Host:Yeah, yeah, especially, I mean, you’ve got that balance of I guess, you know, there’s a lot of human research that goes on that the astronauts do to themselves, right, to understand what is happening to the human body in space. And I’m sure there’s other human research elements that are being done for people here on Earth, right? Or maybe it kind of even translates just the NASA studies and the U.S. National Lab studies.

[00:08:24]

Patrick O’Neill: Sure, so what I would say is think about a lot of the research that was happening on the Space Station, or even with the shuttle program bay in the day, that was focused on the astronauts, and kind of using them as the guinea pig, so-to-speak. But then you now have– so you’re able to understand basic concepts of life science research, or how bodies adapt, or in a microgravity environment. So a lot of the pre-research that was done has now set the foundation for a lot of the research that is going up from pharmaceutical companies. So NASA really set, or paved the way for a lot of the research that’s going up now. Because now it’s much more targeted, I think, based on a lot of the early findings that were had with astronauts in space for extended periods of time.

[00:09:10]

Host:Okay, so yeah, it kind of benefits everyone both ways, right?

[00:09:12]

Patrick O’Neill: Absolutely, yep.

[00:09:13]

Host:So you’ve got, you know, the citizens, but then also the astronauts. There you go. Okay, so let’s talk about just, you know, CASIS and NASA. So you said, you know, Congress decided there needed to be a non-profit to manage all of this, so NASA didn’t have to do it. And, you know, we can build this sort of industry of research that goes up into microgravity. And that’s where CASIS comes in. So how is the relationship there with NASA and CASIS, and then with, and you said it was research partners, industry, how does that all work?

[00:09:47]

Patrick O’Neill: So what I would say first and foremost is that, you know, NASA and CASIS, you know, we truly like to use the concept that we are powered through partnership. Everything that we do, and I talk with your team on a daily basis headquarters, and, you know, so from a PR perspective, there’s an awful lot of strategy in place from a communication perspective. There is equally the same thing from a program science perspective, you know, what are kind of the goals and objectives that we’re all collectively trying to do so that we can communicate effectively to the public and to the research community that they could take advantage of this incredible research platform. So, you know, there is an awful lot of back and forth that happens on a daily basis between our collective organizations, and it’s all done, again, with the intention of communicating about the science now, as well as the opportunities that might exist for researchers down the road.

[00:10:34]

Host:So is CASIS the one that actually goes out and finds people to bring research to the U.S. National Lab?

[00:10:41]

Patrick O’Neill: That’s one of our jobs. And, you know, I’m sure that we’ll talk a little bit more about maybe some of the other partners that are involved in helping to bring research to the Space Station and the National Lab, in particular. But yes, that’s one of the definite core functions of CASIS is to seek out traditional partners, non-traditional partners, to try to just educate people, again, on how it is that, you know, your company or your research institution could be benefited from sending their research to the Space Station. And, you know, what I would throw in as a caveat for that, and that’s something that I have a chance to go and do frequently, is helping to tell that story of sending research to station. You know, a lot of times when you go meet with a company, the first thing that they sit there and say is wow, that’s really cool, but how expensive is this going to be? I mean, it just seems like sending something to and from the Space Station, that’s just going to be, you know, time-intensive, labor-intensive, and it’s going to be cost-prohibitive. And so one of the great things that has happened with the National Laboratory is that to send your research to the Space Station, to have the astronaut as your lab technician, to send the research back down, those are costs that aren’t passed over to the researcher.

[00:11:47]

Those are costs that are not passed over to the particular company. Because those are costs that you and I as taxpayers of the United States of America have already made that investment into. So it’s nowhere near as expensive to send your research to and from station, as folks would think. And now you’re able to take advantage of it from a marketing and PR perspective. So especially if you’re talking to major companies, you know, it’s not only what it is that you’re going to be able to learn, but how is it that you’re going to be able to capitalize on this to separate yourself from your competitors, saying that we are doing more to be as innovative as we possibly can, and what’s more innovative than sending research to the International Space Station?

[00:12:25]

Host:Yeah, but then, okay, so you got this cost element, and it seems like there’s a lot of cost that’s absorbed, so that way it makes it, like say it’s not cost-prohibitive. You can actually do this, and it could be affordable, and you could get something out of it, especially from an innovative perspective. But then I’m sure, you know, you, as the marketing PR guy, you have a pitch for what is so great about microgravity, right? What is it that you can bring, what research can you bring to this microgravity environment, the only one that exists, and then, you know, accomplish what you need to accomplish?

[00:12:59]

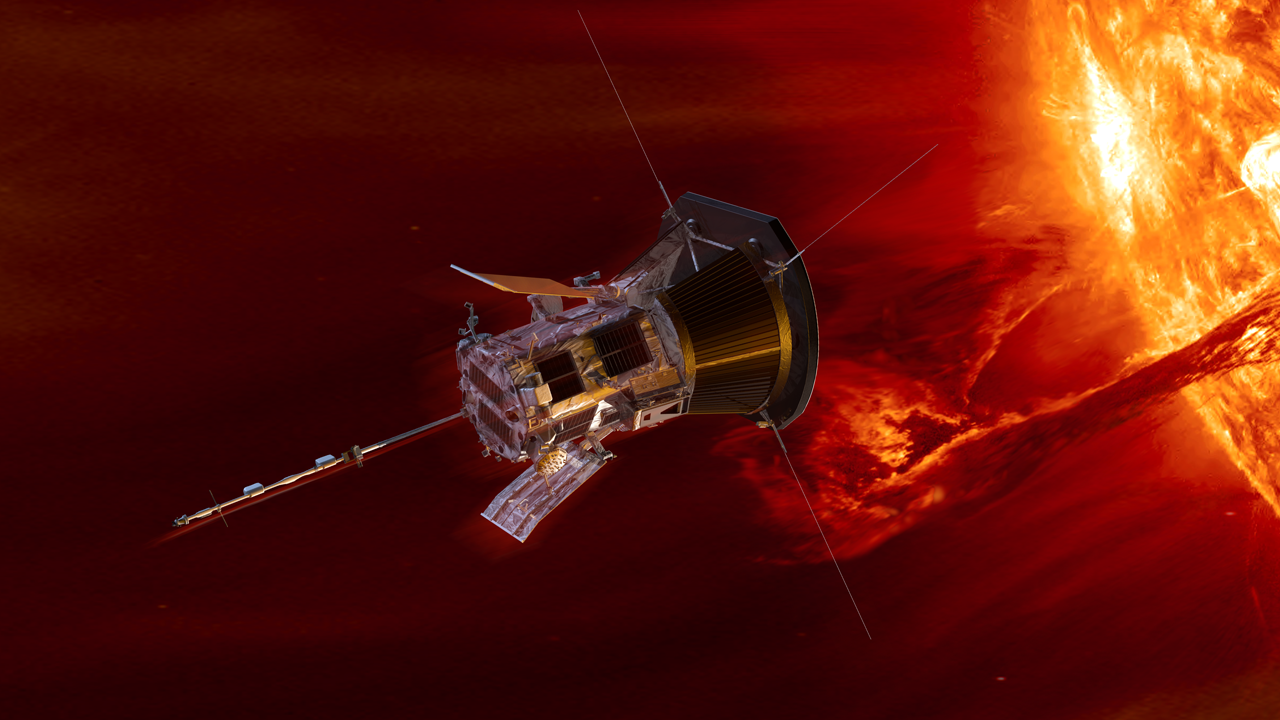

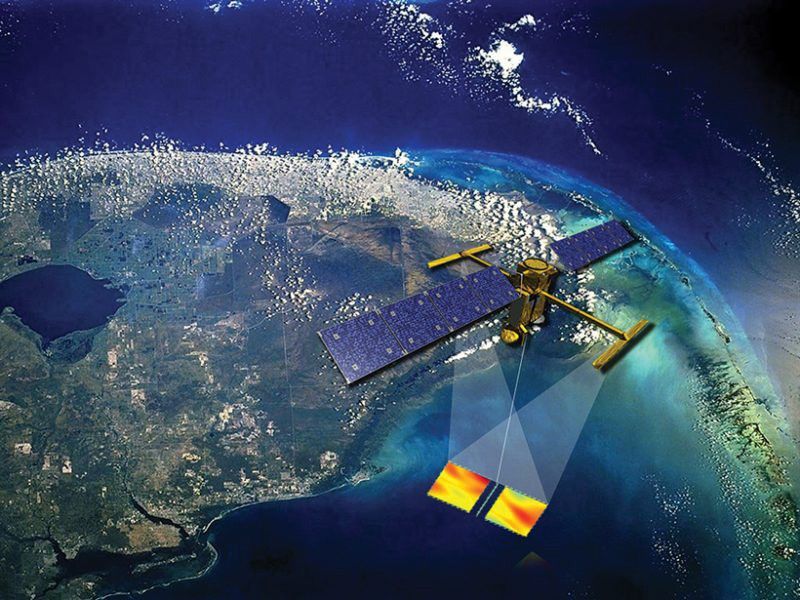

Patrick O’Neill: Yeah, and so, you know, you kind of touched on it. I mean, you know, microgravity, in and of itself, I mean, the fundamental variable that we are all familiar with here on Earth is gravity. It’s always around us at all times. I mean, there might be instances where you could potentially take it away, but not to the level that you can in a microgravity environment like the Space Station has. And so now, you know, you’re able to really look at things in an entirely different dimension than you have ever looked at research previously. And it doesn’t matter what type of research. Life science, physical science, material science, Earth observation, remote sensing, technology development, all of these are scientific factors that here on Earth, you know, again, there’s gravity. Whereas up there, absolutely not. You don’t have that same level of gravity. And you have an opportunity to be, to have your research exposed to this microgravity environment for, you know, 30, 60, sometimes longer than that days. And so from that, you know, what is it that you’re able to learn when you are looking at things entirely different than you’re used to in your typical laboratory setting.

[00:14:02]

Host:Sweet. Okay, so there’s been a lot of research already that has been sent up to the International Space Station. And there’s been experiments that have been exposed to microgravity. So what are some of the things we’re finding? What are some of the cool things that you can get out of sending your stuff to microgravity?

[00:14:17]

Patrick O’Neill: Well, you know, I think we’re going to need another podcast for that one. I mean, but again, I touched on it in my previous answer, it doesn’t matter what type of scientific discipline you’re focused on. I mean, microgravity has the ability to enable findings that, you know, just again, you’re not going to find anywhere else. And one of the cool ones that came out last year, I want to say it was last year, was we brokered an investigation with Kentucky Space, and they sent planarian flatworms to the station, and they were looking to just kind of see how these worms regenerated in a microgravity environment. And they got a pretty peculiar result when one of them came back with two heads. And, you know, something like that, it’s just, you know, you would just not think that that would be the case. And now all of a sudden, you have these worms on station for 30 days, they come back down, and then they just decide that they want to regenerate in entirely different ways. So that’s a perfect example. We’ve sent a variety of rodent research investigations to the station. And we’ve done that for multiple reasons. I mean, first and foremost, rodents represent a model organism that you can take advantage of, and their growth pattern is nowhere near as lengthy as ours.

[00:15:26]

So if you’re able to have rodents on station for 30 days, you know, that might be the vast majority of their adult life. And one of the reasons that you would send rodents up is based on using the astronauts in the past, you know, muscle wasting, bone density loss are greatly accelerated in a microgravity environment. So it almost, it almost truly accelerates that aging process, so-to-speak. And so you’re able to kind of do that similar type of research on a rodent, for instance, and if they’re on station for 30 or 60 days, that might be, again, the vast majority of their adult lifespan because of the fact that they’re in space and it kind of accelerates that growth, that aging process. So what can you do from a muscle wasting or a bone density perspective when it comes to research, and how can that potentially help the aging population here on the ground, or how can it help those that have been wounded in battle? I mean, those are the types of research investigations that have been happening on station and will continue to happen on station, because it’s all about trying to improve the care or the lifespan or the quality of life for those of us here on Earth.

[00:16:28]

Host:All right, yeah, learning a lot, especially, and this is one of those examples that we were talking about earlier, where this kind of goes both ways, right? So you can learn about just what happens to bones and muscles in their microgravity environment. And then get way more samples than you– or examples. So you can kind of learn from them and then kind of bring what you learn and then bring it down to Earth for research on stuff like– and I know one of them that comes to mind is research on osteoporosis, because it’s a big, you know, bone disease.

[00:16:57]

Patrick O’Neill: Absolutely.

[00:16:58]

Host:Yeah, now, I’m sure, when you say you take your research and you send it up to space, right, I’m sure it’s not just you just kind of throw it in the lab, right? I’m sure it’s a laboratory, so there are facilities there. So what sorts of things can researchers or facilities can researchers put their environments in?

[00:17:17]

Patrick O’Neill: And I think that that’s a great segue. Because to your point, it’s not just as easy as just, you know, throwing it up there and seeing what happens. Anything that goes to the station first and foremost has to be sent up in flight certified hardware. And so when I talked earlier about, you know, the flight up, the flight down, the astronaut as your lab technician, all of those are costs that are not passed over to the researcher. So then that leads to the question of, well, what is the out-of-pocket cost that’s going to be passed over to the researcher? And it’s sending your research up in that flight certified hardware. And there are multiple companies, and this is one of the great things about station two, is it’s not just a research angle, it’s an opportunity for companies to be able to validate their research facilities, their ability to send research safely to and from Earth to a microgravity environment. So it’s really kind of spanning a lot of different areas of opportunity. But as far as research facilities on station, you know, there’s a lot of things that are very similar to that of your normal lab here on the ground.

[00:18:23]

I mean, so we talked a little bit about rodents. So we have a rodent research habitat. There’s centrifuges, there’s a 3D printer that is on station now, there is, let’s see, we have a microgravity glove box that enables a wide variety of scientific discipline to include using a furnace on station. We have an external platform. If you want to put research on the outside of the station and test it in the extreme environment of space, that is now available to you. There is a DNA sequencer on station. I mean, there’s so much that’s going on that, you know, and again, it’s not dissimilar from a lot of other lab settings that you would conduct your research in on Earth.

[00:19:03]

Host:All right, okay, so lots of different options too. And there’s a lot of cool ones too. I mean, you can put your stuff outside the station and see kind of what happens to it. I mean, I’m guessing from like a radiation perspective, maybe from a temperature perspective, lack of pressure, or, you know, there’s a lot of different things that you can find out.

[00:19:22]

Patrick O’Neill: Absolutely. Yeah. I mean, and to your point, you know, temperature variation, radiation, levels, I mean, those are some of the big critical ones that we talk about with perspective users of those external platforms.

[00:19:35]

Host:So a lot of the facilities and a lot of these kind of experiments, do they require astronauts to kind of have hands-on experience, or are there some that are just kind of running in the background?

[00:19:46]

Patrick O’Neill: So that’s, first of all, that’s a grade segue as well too, because I think that one of the issues that we run into, both from a CASIS standpoint, National Lab, and NASA, is, you know, you can only use the astronauts for so much time when they’re on station. And so in a perfect world, is there a scenario where you’re able to send research up into kind of a rack space where it’s almost like a plug and play future, it’s a simplistic environment where the astronaut just, again, pushes in this cartridge, so-to-speak, flips a switch, and the next thing you know, you have a science experiment that’s going to be conducted for the next 30 days. So we have a mixture of both, where there are hands-on, more astronaut-intensive investigations. An example of that would probably be something like road research or research that’s being taken place in a microgravity glove box or DNA sequencing. But then you also have a couple of companies that have rack space on the Space Station. And the two companies that come to mind are NanoRacks and Space Tango.

[00:20:48]

And think about that as facilities that are in a position to enable inquiries from life science to material science, and they just kind of go in this rack space, so-to-speak, and they kind of sit there for 30 days, and just it really depends on what the researcher is looking for. If they want to have a camera on the inside, if they want to have, if they want to test levels, if they want to, you know, have a light on, things like that, I mean, all of those could be configured based on the needs of the researcher. But it’s done with the intention to really simplify the process, get as much research up as possible, and not have to take away from all of the time that the astronauts are using on station for other, other endeavors that they’re involved with.

[00:21:28]

Host:Exactly. And I know crew time is always just a hot commodity because they have to do so much. I mean, just coming up next week, they have to– and all of this week, they’ve really been preparing for a space walk, or I guess two this month. And it’s just, you know, that’s a huge chunk of time that they have to prepare, because, you know, space walks are very I guess just labor-intensive. They’re out there for six and a half hours. They’ve got hours beforehand of prep, hours afterwards of debrief. It’s just a long day, and everything has to be coordinated down to like the minute. I guess you can even say second, but I’ll just say minute to make sure that the whole time is absolutely maximized. So they dedicate all this time beforehand, and then that, you know, they don’t have as much time for research because they have to do everything up there, you know? There’s no, there’s no astronaut and then a lab technician and then plumber, you know? They are all three of those things. So it’s crazy what they have to do. Sol I guess that’s kind of helpful when things kind of run on their own.

[00:22:31]

But you’re right, there’s stuff that, you know, if you’re going to sequence DNA, you actually have to inject it. You have to have an astronaut go in the glove box and put something in a DNA sequencer, or actually, you know, work with the rodents in the habitats. So, I mean, finding that crew time can be a little bit challenging at times I’m guessing, right?

[00:22:51]

Patrick O’Neill: It can be. And that’s why, you know, we work in partnership with NASA to really kind of understand and identify the projects that are coming down our pipeline conversely with what it is that is a priority for NASA. So that way whenever we do send research up, we are able to maximize everyone’s collective time.

[00:23:07]

Host:Okay, cool. So that thought makes me think of, or kind of lead to the whole process of getting research onboard the Space Station, right? You said, kind of your process. So what is that like? Now let’s say you’ve gone out, you’ve connected with an industry or with a researcher, and they want to get something out in the International Space Station. What does that look like?

[00:23:30]

Patrick O’Neill: So the way that it would work is first and foremost, if you do want to send research to the Space Station, you’ve got to submit a proposal. So you have to submit a white paper that basically says, this is what I want to send to the Space Station, this is why I think the microgravity can enhance the findings of what it is that I’m presently doing on the ground. And so we have this kind of open forum where we allow anybody to submit a white paper at anytime, and then our team will evaluate that. And so as we are starting to evaluate these, first and foremost, the question we have to ask ourselves is, you know, does it need microgravity? I mean, is this something that can be done in your lab settings, or, you know, is it going to make sense to be done in a microgravity environment on the Space Station? Second of all, is it operationally feasible? Is it something that we can put into a facility that already exists on station? Is it something that’s going to be safe to have beyond the Space Station? We don’t want to endanger the lives of the astronauts. And then once we’re able to kind of identify where this payload might end up going once it goes to station, then it passes over into kind of meat and potatoes, which is the science portion of it.

[00:24:35]

Okay, you know, what is the science relevancy of this? What is the tangible impact for benefiting life on Earth? And then all of these are, from a science perspective, evaluated from our science team, as well as subject matter experts that are not CASIS employees, because again, at the end of the day, we are good stewards, we want to be good stewards of this incredible research platform. You know, we don’t want to be looked upon as just picking and choosing our favorite research from a Fortune 500 company. It’s about science and science relevancy. And so once you kind of go through that portion, then is segues then into, you know, working with NASA, working with hardware partners that, again, we mentioned earlier, like the flight-certified hardware portion. So, you know, teaming up the researcher with a flight-certified hardware partner who can, you know, take that concept and morph it into an actual experiment that can go to station, that we manifest it, that it flies up, and then it gets, the research gets conducted. And then in some instances, the research comes back down for further evaluation.

[00:25:37]

And then in other instances, it either stays on station for an extended period of time, or eventually it will be put into the signal capsule, which then burns up in the Earth’s atmosphere when all the research is done on Orbital ATK mission.

[00:25:52]

Host:Okay, and then the way it gets back is SpaceX, right? SpaceX is the return vehicle?

[00:25:56]

Patrick O’Neill: Right.

[00:25:56]

Host:Yeah, yeah, yeah.

[00:25:56]

Patrick O’Neill: Yep, so SpaceX is the return vehicle presently. But then hopefully in a couple of years, we will be able to have our friends over at Sierra Nevada, which will equally be in a position to send research back down to the research community.

[00:26:07]

Host:Oh, that’s right, yeah, they have a return capability too. Okay, cool. Yeah, no, a lot of different options. All right, so you get this proposal, and then you’re connected with flight hardware so you can kind of fit your experiment in this flight hardware and make sure everything is going to be working. And then you kind of work with commercial resupply company to actually send it up to the Space Station, right?

[00:26:31]

Patrick O’Neill: Right, so, you know, think of SpaceX and Orbital ATK as kind of the transportation to and from. But all of, you know, it’s not as though we work directly with SpaceX or Orbital ATK. We actually work directly with NASA to identify the various payloads that are going to be going up. Because, again, at the end of the day, there’s only a finite amount of payload space that we all have. And so it’s working with NASA to understand the research priorities that they have on a particular mission, and us then being able to sit there and say, okay, you know, we want to put these number of projects in. How is that going to coincide with the research that NASA wants to send on this, you know, call it Orbital ATK mission?

[00:27:14]

Host:Okay, cool. Yeah, a lot of players in there. I mean, you’ve got CASIS, NASA, the commercial partners, you know, flight hardware providers, researchers, Fortune 500 companies. Oh my gosh. This can be get pretty expansive.

[00:27:26]

Patrick O’Neill: It’s clear as mud, right?

[00:27:29]

Host:So how has this evolved over the years? Has this been kind of a growing thing? Or did it kind of explode all at once? What’s the story behind this whole industry?

[00:27:39]

Patrick O’Neill: I would say it’s a very growing thing. You know, I’ve been lucky enough to be with CASIS for just about six years now, which is the vast majority of the lifespan of the organization. So, you know, I’ve been privileged to kind of see how this has evolved over time. And, you know, I can say that when the ISS National Lab was first created, I think that there was a notion that overnight, you would just have all of these companies and researchers that are like, oh my gosh, I can’t wait to send research to the Space Station. But that wasn’t the case, you know? And I think that we realized that and recognized that very early on here at CASIS that companies didn’t know that they could access station. Their researchers didn’t know they could access station, let alone why they would want to access station. I mean, what could I learn in microgravity that I can’t learn in my own lab? So the first couple of years of the organization was not only standing ourselves up, trying to figure out who we are and how we fit in this overall Space Station landscape, working with NASA, but also trying to work with the research community to let them know why they should want to take advantage of this Space Station.

[00:28:45]

So it took a couple of years to really help build up that notion of demand. And, you know, now we’re starting to get into the golden years of the Space Station, as I like to say. And so last year was a perfect example where we had, you know, an many thanks to our partners over at SpaceX and Orbital ATK, you know, we had a terrific year of continuous research to and from station. And from that, you were really able to see a lot of the fruits of the labor of the hard work of NASA, of the CASIS team, along with our commercial partners like, you know, NanoRacks and Space Tango who are equally kind of bringing in their own research. And so the demand portion has kicked up exponentially over the last couple of years. And, you know, part of it is, you know, a derivative of having some recognizable commercial brands that are now starting to send their research to station. And part of it is also just, you know, over time, you know, enhancing how it is that we put together our pitch and educate people on how they could take advantage of station.

[00:29:46]

So it’s been a process, but I would say that it’s been an incredibly fun and unique process for all of us to be involved with. And, you know, now we’re really able to, again, kind of enjoy the fruits of the labor.

[00:29:58]

Host:Yeah, exactly. I mean, if you think about it, it’s all kind of new, right? I mean, you think about it, things going to space. That’s a NASA thing, right? You know, you’re talking about space agencies, international partners, like these big time players in the space world. But now, you know, now you’re going to open it up to so many different people to actually send stuff to space. And the space industry itself, I see it all the time just constantly growing and people talking about it. It’s kind of cool to see this thing kind of grow, expand and mature, I guess.

[00:30:32]

Patrick O’Neill: Well, and, you know, on top of that, too, I mean, it’s funny, I was reading an article the other day where they were talking about the emergence of the suborbital research community. And, you know, one of the things that we talk about with suborbital research is that it might be a great precursor to setting the foundation for even better research on the International Space Station. So, you know, you now even have that community that is now part of this quote unquote space race, if you will. So there’s just so much activity that’s going on right now, both from a NASA standpoint, a Space Station standpoint. You have all of these commercial launch providers that are now starting to get into the mix. I mean, you know, you have to sit there sometimes and say, one of the reasons that they’re all getting involved is because they see the opportunity, they see the demand is beginning to swell. And the Space Station is very indicative of that.

[00:31:22]

Host:Yeah, I like the way you say it, too. It’s kind of like the golden age. But, you know, with competition comes innovation, so that’s kind of exciting as well. So, you know, kind of leading, I guess leading into that is the kinds of research that we’re seeing. Now that this industry is maturing and people are sending more and more things and there’s recognizable players in the research space, you know, what kinds of research can we see go through CASIS and occur on the International Space Station?

[00:31:51]

Patrick O’Neill: So, you know, again, it really spans all scientific disciplines. But, you know, as we’re kind of forecasting into 2018, you know, I guess it gives me a good opportunity to plug some of the research that we’re expecting to have go up hopefully in a couple of months on the next SpaceX resupply mission.

[00:32:08]

Host:Okay.

[00:32:08]

Patrick O’Neill: And, you know, it really, it’s kind of a diverse set. I mean, so we have research that’s looking at wound healing. We have research that’s looking at metabolic activity tracking. We’re going to be having two new facilities that are going to go on station that help to enable further research. One of them is going to be kind of an updated centrifuge. And so that centrifuge is going to be able to, you know, have research almost be side by side. Maybe you have one that is, you know, reacting because of microgravity, but then you have a centrifuge right next to it, and maybe you’re trying to create conditions that are similar to what it’s like on Earth. So you have this, you know, these two differing types of investigations that are now happening right next to each other. And you’re not having to do one research on the ground simultaneously with another one in space to see kind of, you know, what the reaction difference is. Now you’ve got them right next to each other. So that’s kind of a cool principle for researchers to take advantage of. Another research platform that’s going to go up, it’s called the missing platform. But it’s going to greatly enhance materials research investigations on the Space Station.

[00:33:12]

So, you know, those are two new facilities that are going to be going up, again, adding to the already very diverse amount of facilities in research that’s possible. We even have, you know, student investigations that are going to be going up, some looking at genetics. And then NASA’s got a wide variety of payloads that are going to be going up too. So, I mean, there’s an awful lot that’s happening right now. I also want to say, plant biology research is going to be another fixture that’s going to be involved in this upcoming mission. So all sorts of stuff going on.

[00:33:43]

Host:Yeah, definitely. We actually had a couple, you know, things come back on SpaceX 13. You know, when you’re talking about research going up, and then, you know, some of it kind of stays there, some of it burns up, some of it comes back, there’s plants that were actually on SpaceX 13, right?

[00:33:58]

Patrick O’Neill: There were plants, yeah. There was a couple of different plant biology experiments that went up. One from an academic institution, and then one from a very recognizable commercial brand. But, you know, I think that, you know, plant biology research is a great example that it spans all sectors. You know, NASA has been doing plant biology research on station and on shuttle for years. I mean, you know, the Veggie project is something that has gotten great visibility as astronauts try to get beyond low Earth orbit, they’re going to need to harvest or create their own food supplies. So NASA has been involved in that. But then you have academic researchers who are looking to just kind of ask those basic questions of how do plants react when, you know, you no longer have gravity as a variable? Which ways do they grow? Why do they grow that way? You know, what happens when you don’t have that much sunlight on them, you know, how do they react? But then you also have commercial companies that are now sending plant biology research experiments to station with the intention of improving agricultural processes here on the ground. But, you know, again, it’s really hitting on so many different areas now.

[00:35:02]

I mean, again, whether it’s government organizations, academic researchers, commercial companies. And all of that, in some ways, is kind of what you want for the National Lab. You want a variety of thoughts and ideas for how to tackle various types of research.

[00:35:15]

Host:Yeah, definitely. Well, Veggie is a great example because Veggie is a facility, right?

[00:35:20]

Patrick O’Neill: Right.

[00:35:20]

Host:So it’s a place where if you need to do plant research, this is where you’re going to do it. It’s one of the places on the Space Station where you can do it. And it’s just from, you know, kind of playing with plants in space that they’ve come up with, all right, we’re going to use, we’re going to use lights, these LED lights, and we’re going to use these things called pillows, and they’re going to grow in these pillows where it has all the soil and nutrients and nutrient delivery system. And then they just came up with this place. And now boom, if you want to grow a plant or see what happens to a plant, this is where you’re going to do it. And, you know, the one you said before was Outredgeous red romaine lettuce. That was actually the first time that Americans ate lettuce on the station. That was pretty cool.

[00:36:01]

Patrick O’Neill: That was pretty cool. Well, and, you know, so projects like that bring I think great visibility for, you know, exploratory purposes. But then there’s also a lot of projects that are happening on station that have kind of a dual usage or, you know, NASA and CASIS and the ISS National Lab working together in partnership. And one of the ones that just came back too was a run research investigation where, you know, think of NASA as kind of being the leaders of the rodent portion of it, and then the National Lab working on kind of the research side of it. So the Houston Methodist Research Institute partnered with pharmaceutical giant Novartis, and they were looking at implantable chips in rodent research, again, with the hope of ultimately improving life on Earth, whether that be through cancer understandings, as well as things like osteoporosis and diabetes.

[00:36:56]

Host:Whoa. Okay, so it’s a device that can actually be implanted and kind of help out with that, right?

[00:37:01]

Patrick O’Neill: Right, and hopefully better monitor conditions within your body.

[00:37:05]

Host:Yeah, yeah, yeah.

[00:37:06]

Patrick O’Neill: Then also, you know, speaking of something like that, we also had another one that just came back down that was a glucose biosensor that was looking to improve day-to-day diabetes management. So the efficacy of insulin being, you know, disseminated into the body to make sure that it has max potency.

[00:37:25]

Host:Okay, yeah. So a lot of like, you know, a lot of these medical kind of industries kind of in this space, right?

[00:37:32]

Patrick O’Neill: Yeah, I would say, you know, think about it like this too. It’s almost, you know, like low-hanging fruit, if you will. So we see an awful lot of pharmaceutical companies that have been involved in life science research on station. But again, a lot of that kind of pre-dates the National Lab concept, and was really kind of harkening back to the research that NASA was doing, specifically on the astronauts, living and working in space. And then, you know, some of those, some of those basic understandings now being passed over and allowing the private sector to be able to take advantage of some of those early findings and now incorporate that into their research that can hopefully create therapeutics or drugs that can improve patient care here on Earth.

[00:38:12]

Host:Nice. All right, so the glucose biosensor one, that one, I saw a picture of it. It’s like super tiny, right? It can fit on your finger.

[00:38:20]

Patrick O’Neill: Fits the little guy.

[00:38:22]

Host:Yeah, so my question is how– what about microgravity makes the Space Station a good place to test that tiny little sensor?

[00:38:32]

Patrick O’Neill: So it’s not so much the sensor itself, but I think that it was more focused on the fluid flow of, you know, kind of shooting out that insulin and making sure that it is as efficient as possible. So, you know, you send, you know, you send this thing up with the insulin or a mockup thereof, and again, kind of see how that flows in a microgravity environment. Again, done with the intention of really maximizing every time that it kind of shoots out into your body.

[00:39:02]

Host:That’s right. Okay, yeah, making sure that it’s consistent, right? No matter where it is or what you’re doing.

[00:39:07]

Patrick O’Neill: Not just consistent, but, you know, that it’s also giving you the most powerful and most effective kind of shoot so that way it gets into your blood as fast as possible, and you’re able to kind of go about living your life in a normal capacity as opposed to, you know, maybe waiting 15 to 20 minutes. Maybe this is going to be much more instantaneous into your body.

[00:39:27]

Host:Yeah, okay. Yeah, there’s a lot of cool studies. Another one on SpaceX 13 that I’m thinking of. They are actually trying to manufacture fiber optic filaments, right? And try to figure out, you know, like space manufacturing, right? So I guess are they trying to build a space manufacturing kind of industry? Or just kind of test its capability on Earth and kind of the same thing, right? Make sure it’s as powerful, as consistent, that kind of thing.

[00:39:56]

Patrick O’Neill: Right, yeah. So our partners over at Made In Space, they are also quite famous for having the 3D printer on station. They kind of wanted to take that next step into looking at on-orbit manufacturing capabilities. And so, you know, that’s kind of where you’re looking at fiber optic technology, which, you know, could potentially enhance, you know, I guess a lot of the things that might be happening within the advanced communication, or, you know, DOD type communities. So, you know, Made In Space was looking to see, you know, how do these filaments react in a microgravity environment? Can I grow them, you know, more purely so that maybe it’s something that is grown in space, or, you know, harvested, if you will, even though it is fiber optic technology, but then taking that back down to Earth and actually selling that. So, yeah, I mean, how can we use the Space Station as an ever-evolving platform, not only for research, but also, again, for on over manufacturing capabilities. It really is kind of an interesting way to think about the Space Station as we continue to move forward.

[00:40:57]

And there’s going to be other companies that are equally looking to do similar types of on over manufacturing capabilities in the future. And that’s almost, again, when we’re talking about the Station, that’s what makes it to exciting right now. It’s not just research, and it’s not just, you know, the commercial companies that are sending research out, or academic researchers, but it’s companies being able to leverage microgravity to enhance their business findings, and, you know, validate why it is that we need to continue to have a commercial presence in low Earth orbit, potentially beyond this Space Station.

[00:41:29]

Host:That’s right. You know, one of the things that always comes to mind when it talks about growing stuff in space, the thing that I always think about is protein crystals, because that was kind of– that one was kind of, I guess you can call surprising, because they actually grew differently, and I guess you could say almost more perfectly, because they didn’t have stuff weighing down on them. Was it a positive finding?

[00:41:53]

Patrick O’Neill: It’s a very positive finding.

[00:41:55]

Host:Yeah.

[00:41:55]

Patrick O’Neill: So, you know, there’s a variety of companies that have been doing protein crystallography research, or academic researchers that are looking at protein crystals. And I think that you actually kind of hit it on the head. You know, in a microgravity environment, you’re able to grow crystals in a more uniformed or perfect manner, which would potentially allow for you to dig in and better understand the genetic makeup of some sort of a, you know, a protein. And, you know, one that comes to mind for me that has gone up multiple times is we have partners over at Merck Research Laboratories, and they have sent three separate, I want to say, protein crystallography experiments, and it’s being done with the intention of improving the efficacy of KEYTRUDA, which is an FDA-approved drug that is now done for cancer patients. And so right now, even though the drug is already on the market, if you go and, you know, you get shot up with this, you’re basically in the hospital for an entire day. So what Paul Rickert, the lead researcher over at Merck is trying to do with these protein crystallography experiments, is grow these crystals at a better rate, a larger rate, so that, again, he can dig into the genetic makeup of these proteins and find a way to improve the potency of this drug so that instead of you, as a patient, being at a hospital all day, you know, maybe you just go see your doctor, and he gives you a shot, and 10 minutes later, you’re walking out the door, 30 minutes later, you’re out playing golf.

[00:43:20]

I mean, you know, it’s about trying to make your life a little bit easier. But, yeah, so cool stuff like that with a protein crystallography experiment. But yeah, again, it’s really trying to make things a little bit larger so that you can dig into them and look at genetic structures of proteins in a new and novel way. And microgravity, it’s not to say that you can’t do protein crystallography on the ground. But microgravity has shown a propensity for having much larger crystals, because, again, you’re no longer having the push and pull of gravity as a vector. Now you have microgravity around you, and it really allows for these crystals to grow in much more of a natural state, so-to-speak.

[00:44:01]

Host:Super cool. I love it. You know, so you’ve got things that are actually growing I guess more perfectly, and you said larger in space, but I know that using the Space Station can actually make things a little bit less expensive too. I think a good example is satellites, actually launching satellites.

[00:44:20]

Patrick O’Neill: Yeah.

[00:44:20]

Host:Do you guys work with companies to launch satellites from the Space Station?

[00:44:24]

Patrick O’Neill: So there is one company in particular that we work with who, you know, not only do they have rack space on the Space Station, not only do they have an external platform on station, but they also have the ability to send cube satellites into low Earth orbit from the Space Station. And that’s a company called NanoRacks. And so we work in partnership with them. All of their research that flies to the ISS flies under the ISS National Laboratory manifest. And so we work with them to identify, you know, which cube satellites they want to send, why they want to send it, and the timeframe behind it. And so, you know, that’s a perfect example of it’s not just CASIS as, you know, going and securing research. It’s some of these partners like a NanoRacks or a Space Tango who are working with researchers, and equally kind of talking about why it is that they would want to send their research to Station, or [inaudible] research from Station. And so NanoRacks is the entity that we work heavily with who is responsible for, again, deploying those cube satellites.

[00:45:29]

Host:And they’re called cube satellites because they are much smaller than like a satellite that you would normally think about, right? When you think of satellite, you think of like this giant floating dish in low Earth orbit, right? But they are much smaller.

[00:45:41]

Patrick O’Neill: They are much smaller. You know, think about it as, you know, your satellite being housed in a shoebox. And that shoebox just being shot out of the Space Station. And, you know, maybe it gets a little bit bigger once it gets outside of the Space Station parameters, but maybe it doesn’t as well. I mean, it just really depends on what the researcher is looking to try to do and how big they want to go.

[00:46:04]

Host:So what do these small satellites do? What are they capable of?

[00:46:08]

Patrick O’Neill: Wow, you know, what aren’t they capable of, you know? I mean, so, you know, I think when you think of satellites, the typical idea would be, you know, Earth monitoring in some capacity. But, you know, there was one that went up, I want to say it was on SpaceX-CRS13, or Orbital ATK-8, but it was actually E. Coli was put in a satellite and sent into low Earth orbit to kind of see how it reacts and morphs in a microgravity environment. But, you know, obviously it’s being [inaudible] away from the Space Station. So I don’t really know what the findings of that were. But something like that is pretty doggone cool, where, you know, it’s not just, you know, true satellite technology, but, you know, now, you know, sending life science into, in a cube satellite, and seeing how that reacts in the extreme environment of space.

[00:46:57]

Host:Sweet. So there’s like this fleet of shoeboxes just kind of circling around here. That’s what I’m imagining. I don’t know. They’re all doing all different kinds of stuff, right?

[00:47:07]

Patrick O’Neill: They are doing all sorts of cool work, yeah.

[00:47:09]

Host:Yeah, yeah, very cool. All right, yeah, lots of different, lots of different research going on, and CASIS is kind of at the center of that, kind of managing this back and forth of research, going up and down and all around. So that’s awesome. I did want to kind of end with this cool contest that you’ve got going on right now. Do you want to talk a little bit about that?

[00:47:30]

Patrick O’Neill: Right, so, you know, I get the fun job, I guess, where, you know, I get to go out and talk with you about research at a very high level. But then also I get the opportunity to work alongside some truly unique partners who can bring great visibility to the Space Station. And also, you know, I think that one of the areas I forgot to touch on earlier was that one of the key functions of CASIS and the National Lab is to help inspire and engage the next generation of scientists and engineers. And so every year what I’ll typically do is I’ll work with a unique brand to develop one mission patch that represents all ISS National Laboratory research. So last year, for instance, we worked with Lucasfilm who developed a Star Wars themed mission patch, which was pretty doggone cool. And then in 2016, though, and this is kind of where, you know, a longwinded response, where we’re kind of getting with this contest, in 2016, we partnered with Marvel, and they developed a mission patch that featured Rocket and Groot from the Guardians of the Galaxy franchise.

[00:48:27]

Host:Cool.

[00:48:27]

Patrick O’Neill: And so what I was hoping to try to do out of that was not just have a mission patch, which brings, you know, some awareness to the Space Station. But is there a way to create an actionable item that we can take from this mission patch and spread it to the masses? And so what we ended up doing is working with Marvel to create a stem competition that is focused on Rocket and Groot and the characteristics associated with them. So we now have a contest that is live for students in the United States aged 13 to 18. And, you know, they can just simply go and submit flight concepts on the characteristics of Rocket and Groot, and, you know, for instance, you have Rocket, who is general innovation, and, you know, enabling technology development, material science. But then you have Groot, and he is kind of like the personification of plant biology or regeneration. So students, you know, how could you do something on the Space Station that’s focused on regeneration or seeing how plants or something like that react in space?

[00:49:30]

So, you know, we’re really trying to encourage students to think about their favorite superheroes in a new and different way, and equally link that to how the Space Station could create some fun stem opportunities.

[00:49:42]

Host:Cool. Okay, so they’re designing research for each of these teams, or is it like a set, a set thing that they have to accomplish, like what’s the whole contest?

[00:49:53]

Patrick O’Neill: So the contest itself is actually fairly basic, where it’s truly submitting a white paper. You know, if you want to, if you’re interested in material science, and, you know, thinking about, you know, how Rocket would want to do research on the Space Station, you know, what would you send to the Space Station? Why would you send it? What could you learn that you can’t learn here on Earth? Conversely, you know, if you’re a fan of regeneration, you know, how can microgravity enhance regenerative medicine? You know, submit a concept on what you want to send, why you want to send it. I mean, it’s basic, yet at the same time, what we’re going to end up doing when the contest is done is we’re going to select two concepts, one from Team Rocket, one from Team Groot, and we’re going to turn those concepts into actual experiments, and they will launch to the Space Station later this year.

[00:50:44]

Host:Ah, sweet. Yeah, there’s your actionable item, right? An actual thing that a student design that is going on the Space Station.

[00:50:51]

Patrick O’Neill: Yep, an actual, an actual item. And, you know, the cool thing for the students, too, is they’re going to have the chance to, you know, not only put this concept, you know, together, but they’re going to work alongside our hardware partners, our engineering partners, to make this, you know, something that can truly be turned into an actual experiment. So, you know, you’re going to get an awful lot of practical application if you’re a young student. And, you know, I can’t think of a better thing to put on your resume than to sit there and say that, you know, over the summer or over the second semester, I got a chance to put together an experiment that flew to the International Space Station.

[00:51:25]

Host:Man, I wish I could put something like that on my resume. That would be cool.

[00:51:28]

Patrick O’Neill: Well, there’s a reason why, you know, I went to a state school and not a smart person’s school.

[00:51:33]

Host:Hey, me too, man. I’m a marketing PR kind of major too. So I look up to these guys for sure, because what they can accomplish is just astounding.

[00:51:44]

Patrick O’Neill: Absolutely.

[00:51:44]

Host:Especially to get students involved this early, you know? Because if I had known, you know, there was a Rocket and Groot kind of contest and I could submit something, you know, maybe I would have went the science route. Well, looking back, I don’t know. We’ll see. I’m happy where I am now. I’m happy where I am now. But still, it’s just, it sounds like an amazing opportunity.

[00:52:02]

Patrick O’Neill: It does. And, you know, I guess I have to actually give it the official title for the contest, or the challenge, is the Guardians of the Galaxy Space Station Challenge. So, I mean, if I’m doing shameless plugs, then, you know, if you are a student, if you’re a teacher and you want to pass this over to your students, if you’re a parent and you want to pass this over to your child, you know, I would say that go to the following website, spacestationexplorers.org/marvel, and you’ll be able to find not only information on the contest, but you’ll also be able to find examples of research that’s been done, both from a materials science standpoint technology development, and then also plant biology regeneration. So it’s kind of a one-stop shop that is able to provide as much information as possible for the students to be dangerous and submit their concepts.

[00:52:48]

Host:How long is the contest going on?

[00:52:50]

Patrick O’Neill: I wish I could say it’s going to be going on in, you know, like infinitely, but it’s not. It’s going to be pretty quick turnaround. So the contest runs until the 31st. So we have about a week and a half to go. But, again, what I would say is that it’s a pretty basic submittal process. So, you know, we’re not asking for the Moon here, you know, we’re asking for a couple of paragraphs. And, you know, who knows? Maybe your paragraphs are going to be the one that gets selected, and you could be that lucky person that gets to watch your payload fly to the Space Station, and, you know, we can go and spread that to the masses and let people know all the cool research that’s possible on Station.

[00:53:24]

Host:Yeah, definitely. Okay, yeah, we’re definitely going to have to turn this episode around real quick so we can get this out, so we can get it out during the contest, give people a couple extra days and a little extra promotion for it. That’s so cool to send stuff to the International Space Station. Among all this other great research that’s already up there and constantly going up and down, like you said, the golden age of research onboard the International Space Station. Patrick, thank you so much for coming on and talking about the National Lab, and just explaining how this whole process, how this whole, I could say industry at this point, how this whole thing works. So I really appreciate you coming on.

[00:53:59]

Patrick O’Neill: Absolutely, Gary. This was a lot of fun. And we touched on a lot of different subjects. And hopefully we didn’t confuse everyone too much.

[00:54:07]

Host:I love this. So this is definitely my world. So I really appreciate it. And we’ll kind of reiterate those links that you said at the end there after the credits here. So once again, thanks, Patrick, and good luck with the contest.

[00:54:21]

Patrick O’Neill: Thank you very much. Happy Friday.

[00:54:23]

[ Music ]

[00:54:49]

Host:Hey, thanks for sticking around. So today, we talked with Mr. Patrick O’Neill about CASIS and everything about the industry that’s kind of growing as we talked about during this, during this podcast. But at the end there, he was talking about a contest that’s going on right now. So I’m going to kind of start with that. So again, that link that he talked about is spacestationexplorers.org/marvel. You can go there, and then they kind of give the outline of the contest that’s going on and what you need to do to submit your proposal, and as Patrick said, the white paper. Again, that contest is running through January 31st. So make sure to turn those around pretty quick. You’ve got a couple more days. But it’s a pretty cool contest. And at the end of it, you may get to have your research proposal turned into actual research that goes on the International Space Station. That’s pretty cool. So if you want to learn more just about CASIS in general, because, you know, we talked about a lot of the research that’s going on, all the time going up and down, that’s iss-casis.org, and that’s their website.

[00:55:53]

You can find out just more about that industry, and then, or about that business, a little bit more about the industry, too, but then all of the different research that’s going up and down. So on social media, CASIS is @isscasis. Twitter is @iss_casis. And Instagram is @iss_casis, as well. Otherwise, you can find me, follow the International Space Station, as we say, almost every show. That’s International Space Station on Facebook. And then @space_station@iss. That’s Twitter and Instagram, as we always say. And then on the ISS accounts, if you use the #asknasa on your favorite platform, you can submit an idea for an episode of the podcast, or maybe ask a question. Even if you do, honestly, we’ve done it before, we’ve seen questions and said, hey, that would be an awesome episode. Actually, I think the space suits episode. And then, yeah, yeah, a couple of them. And I think we have actually more coming up. Just make sure to mention in the #asknasa that it’s for Houston We Have a Podcast.

[00:56:54]

So this podcast episode was recorded on January 19th, 2018, thanks to Alex Perryman and Greg Weisman and the folks at Kenney Space Center, Lauren Mathers, everyone over there, thanks so much for connecting me and CASIS, me and Patrick today, and making this all come together. Thanks again to Mr. Patrick O’Neill for coming on the show. We’ll be back next week.