From Earth orbit to the Moon and Mars, explore the world of human spaceflight with NASA each week on the official podcast of the Johnson Space Center in Houston, Texas. Listen to in-depth conversations with the astronauts, scientists and engineers who make it possible.

On episode 324, the CHAPEA crew checks in on their seventh month in a Mars simulated habitat and NASA experts discuss the impacts that spaceflight has on astronauts’ health. This is the seventh audio log of a monthly series. Recordings were sent from the CHAPEA crew throughout January 2024. The conversation with Dr. Crucian and Dr. Mehta was recorded February 2, 2024.

Inspired by the CHAPEA Mission 1 crew and want to be a part of an analog like this? If you are interested and think you have what it takes to take on this yearlong challenge and contribute to our understanding of what it will take to support human missions to Mars, applications for the next mission, CHAPEA Mission 2, are open. Visit chapea.nasa.gov to fill out an application. Applications are due April 2, 2024.

Transcript

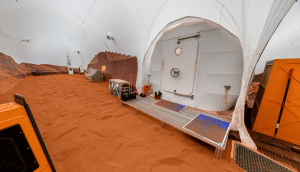

Host (Gary Jordan): Houston, we have a podcast! Welcome to the official podcast of the NASA Johnson Space Center, Episode 324, “Mars Audio Log #7.” I’m Gary Jordan, I’ll be your host today. On this podcast, we bring in the experts, scientists, engineers, astronauts, all to let you know what’s going on in the world of human spaceflight and more. We’re back with another audio log from the CHAPEA crew. CHAPEA, or Crew Health and Performance Exploration Analog, is a yearlong analog mission in a habitat right here on Earth that is simulating very closely what it would be like to live on Mars. We’re lucky enough to have monthly check-ins with the crew, Commander Kelly Haston, Flight Engineer Ross Brockwell, Medical Officer Nathan Jones, and Science Officer Anca Selariu.

To meet the needs of fitting in with this analog and simulating significant communication delays between Earth and Mars that prohibit us from having a live conversation, the crew is recording an audio log based off the questions that we draft for them. On this episode, we play the recording on their seventh month in the habitat, which is here at the NASA Johnson Space Center, and was recorded in January of 2024.

We’ll also be bringing in some special guests to learn even more about CHAPEA. This month is on another angle of scientific research, immunology and virology. A lot of these things that we’ve been talking about on CHAPEA, long spacewalks, dealing with problems, isolation and confinement can have stressors on the human body that may affect an astronaut’s immune system. Returning to the podcast to discuss immunology is Dr. Brian Crucian, who we had on about five and a half years ago to talk about one of the hazards of human spaceflight, diving deeper into the hostile and closed environments, particularly from an immunology perspective. We’re also welcoming Dr. Satish Mehta to the podcast, virologist here at the Johnson Space Center, who has spent the past two decades characterizing the clinical risks associated with virus reactivation in astronauts during spaceflight. The two are working together on the immunology and virology investigation of CHAPEA. So with that, let’s learn from the CHAPEA on how they’re doing, and from Brian and Satish on the CHAPEA immunology and virology. Let’s get into it.

[Music]

Host: Alright, first is CHAPEA Mission Commander, Kelly Haston.

Kelly Haston: Hi, my name is Kelly Haston. I’m the commander of CHAPEA 1, a one-year Mars analog mission out of Johnson Space Center in Houston. So far on our mission, I’ve reported monthly to this audio log that we’re doing great, and the really good news is we continue to really do great. I worry that that’s boring to people, but I actually think that us feeling relatively happy and really just moving along well in the mission is such a good sign and such a delight for me that I can’t help but report it to you all. So I feel like that’s really great. Again, I just can’t commend how much everyone on this mission, both the crew and also the people that support us, just continue to bring their energy and their best self to our efforts because we are doing a lot of things over and over again. And, you know, that repetitive stuff can wear people down. But I really see an energy here that’s just so impressive and I just love it. So, overall, we are solid, strong, happy, and moving right along in this mission.

So in the last month, we have had some exciting highlights happen and they’ve been really nice. So as we neared the end of the holiday season, we actually hit our 50% point exactly. So that was on December 31, which coincided with New Year’s Eve, which was very nice. We were able to celebrate both the new year and also our completion of 50% of our mission. That was such a great feeling and I will put it in terms of some of the activities I do outside of this mission, which is in my spare time, when I’m not being a stem cell biologist, I like to do ultra-running and I run on the trails and I do sometimes races and sometimes just running with my friends for really long stretches, like 50 or a hundred miles. And, you know, those are long stretches, especially the races when you’re going against a time limit and you have to make aid stations at a certain time. And one of my really good friends at home, Stan, he sent me this really cool PDF that showed me where I am, like what aid station I’m at, relative to a bunch of the different races that I’ve either done or would like to do in my life. That was just a wonderful thing because it really reminded me that in a hundred-mile race, you often don’t even think about the race really starting, or like, you know, the hard part getting there until after the halfway point. And so I really felt like that when we hit 50%, it was like, “Wow, look at that. We’re really only at the point where the race is getting started, you know, where the really tough stuff happens. ”And I’m not saying that it hasn’t been tough and we haven’t had our challenges in our first six months, but of course the second half is happily on the way home, on the downhill, but it’s also still going to be tough, right? Now we’re starting to look forward to actually finishing and completing and all that that entails, including getting back to our family. So I would say that 50% was huge to hit that.

Really soon after that, we also hit 200 days on January 11. And 200 days was also just a delightful figure. So NASA has, I think traditionally on the ISS, had pretty big celebrations around a hundred days. And so a hundred increments are very important and, you know, start to mark you towards your full year. And so hitting 200 was really just a delightful sort of milestone for the crew as well. So I think that those two milestones really dominated the last month for me.

Kelly Haston: We were also finishing up a really nice holiday season where we celebrated and really tried to mark some of the things that people do with their families so that we didn’t miss our families as much and so forth. But those were the real key points I would say. I can’t say how happy I am that we’re at this point in the mission and feeling strong and content and really just, you know, doing so well. But one of the things that does actually come up with that sort of idea of, you know, here you are at the halfway point, what are the things that you miss about Earth and that you would suggest for future missions?

So I have two, one is more on the personal side and one is actually something that would accommodate a lot of different scenarios within the mission. So the first is that talking to your family, “talking,” because we don’t talk directly to anyone in our family or friends, is critical in your life, right? You know, maintaining your contacts, talking to the people that you love, taking care of them, helping them, having them help you. So right now, we’re using audio, video and email and all of those are limited for size. So there is some sort of time constraints on how much you can actually send to people, how much content you can send to people. I think that something in the future as the technology gets better for an actual Mars mission that would be amazing is either a hologram or virtual reality setting where your people can tape something for you and then you’re actually sitting with more of a 3D representation, or at least visually seeing that person in 3D. It’s a little bit less limiting or sort of a barrier than the sort of looking at this computer screen. And so I think that would be a really exciting thing to have for future missions where people are actually away for even longer than a year, you know, several years undoubtedly when they go to Mars and are going to be on the Martian surface. So personally, I think a way for you to feel even more attached to your family and friends is critical and would be amazing.

The second thing is a very robust, basically a LIMS system or something that you can actually have, you know, a huge amount of data in a system that’s easily accessible and easily searchable. So I would say right now we have sort of a baseline of that between the things that the crew brought in personally and the things that NASA has provided for us for the mission. But I think that a really extensive system where there’s a lot of references, a lot of ways for the people, the scientists and the astronauts, on the mission to look up anything that they think of because you don’t have internet. So you need a lot of information at your fingertips for, you know, process for the experiments and for the things that you need to know for the mission itself, but also personally. So as an example, as a scientist, I like to read papers, but we’re so used to being able to look up additional information once you read a paper. So you get inspired to be like, “Oh, I want to look at this part of this paper.” And in here, that’s pretty impossible in a quick way. And even to do that, you have to use data, you know, sort of data size to actually get your partner or your friend to send you something to follow up. And it sort of blocks your flow as well cause you’re probably thinking about it in the moment, and then by the time you move on to something else and like a day later get something back from them, it’s kind of gone. So I would say a robust system of resources around information is a critical thing, almost like a computer, like on Star Trek, where you can query things and you can do it in a way that’s interactive and so forth. So that would be something that I think is definitely doable and would definitely, in the future, make a huge difference for the crew in terms of their capability of doing both personal and mission-oriented research.

Kelly Haston: Another question we do get and we talk about a lot, is how this experience of living and working in CHAPEA for a year, with this isolation and with the reliance on three other people, is going to impact your future working and living. You know, and in particular, what your next job will look like. And I confess that it gives me a lot of thoughts around efficiency, about how to pick a job where I know that we’re making the best choices for the money being spent on the task at hand or the research at hand. So I think a lot about that. I also think about how to live my life in a way that is going to make the most of resources and not hopefully siphon off resources. So, you know, we’ve grown a little bit of our own food in here. I do a little bit of that at home. I’m pretty excited to do more of that and maybe broaden the scope of that a little bit. I also think a lot about just how my future job will impact the planet and space exploration and other huge issues that are going to be coming at us in the coming years. And so I think that this experience in here has really inspired me to look deeper into that. But I don’t think that I’ll choose to live with my colleagues in the future the way I am now, despite the fact that we’re working out pretty well.

We do also get a chance to talk to a lot of school kids and, and by talk, I mean, you know, send messages or answer questions to different programs. And so I would say we’ve given a fair bit of advice to different individuals about what to study. So one question could be like, what should the Artemis generation that’s coming through high school right now really look at, what courses should they take? And I would say that one of the key things is still to always, you know, go after what you’re interested in. Don’t just try to force yourself into the hole that you think is going to be most appropriate, but find that thing you’re passionate about, but then if possible, be as broad as possible around it. And an idea of that is, you know, if you want to be a biologist, have some coding skills or have some other types of engineering skills because those will combine to give a richer experience in the area that you’re an expert.

I think engineering in general is just such a thoughtful process, thought process sort of methodology, how to think in, you know, procedures and sort of go through a logical progression of how best to do things is really helpful. So I would say that overall there’s just a lot there where you can combine things. And I was reading an astrobiology textbook in here, and actually one of the people in the book really did point that out. That breadth is going to actually really help you in these fields where you have so much multifaceted, multi-functionality, multi themes and you’re going to bring them all together because there’s nothing in here that’s just one specialty. So I would say while still becoming good at one thing and being valuable for that, you want to have some breadth, and definitely, you know, engineering will really help you if you’re interested in space travel or space exploration.

Kelly Haston: In the next month, we have some cool stuff coming up. We’re definitely going to be engaging a little bit with some remote control items that we get to interact with. And we always like those missions a great deal and then we’re also, you know, going to continue and again, this is sort of like my mantra now, but we will continue to do a lot of the same things that we’ve done before, and we’ll continue to try to do them to our best of our ability. So we’ll continue to be the strong, you know, collaborative unit that we’ve grown into. That’s pretty exciting as we move through the beginning of the second portion of this mission. As always, I thank you everyone for their interest, and I hope you have a really good day. Wishing you the best possible day from analog Mars.

Host: Alright, that was Commander Kelly Haston kicking us off. Really interesting analogy. She talked about being past that halfway point and relating it to her own experiences running ultra-marathons. And of course, those repetitive tasks are going to keep coming up. But a wonderful attitude that Kelly and I’m sure the rest of the crew are going to bring crossing this major milestone. You know, it’s interesting, I guess, we know that they are not having direct conversations with their family, nor with us, right? That’s why we’re doing these audio logs, there’s not really that two-way capability, but the interesting suggestion of having a VR capability to talk with others and really immerse yourself and surround yourself not by the barrier of just a flat screen, is certainly something that I found particularly interesting in that suggestion now six months into the mission. And also that ability to have more information accessible right there on location. Of course, we’ve heard from the crew about their challenges with the internet access and capability, even just that file transfer that they’ve talked about that sometimes taking a long time to transfer files, simulating the Deep Space Network constraints of sending large files really across the solar system for a mission like this. But to have more data readily accessible is certainly something that I thought was very interesting as well. Her appreciation towards efficiency, I thought was interesting as well. It’s something that’s true, I guess, for a CHAPEA mission, but to say that it’s going to be applied in her own life, I found fascinating. But then also, not only that level of efficiency in doing stuff lean, but an appreciation for that impact on the world and an appreciation of Earth and taking care of the planet was, I thought, very interesting.

Of course, I’m sure many of our listeners are thinking, what would it take for me to be a CHAPEA crew member or an astronaut? And what Kelly said is true and consistent with what we find with many of the astronauts that we talk to on this podcast. Find something you’re passionate about, not just something that you think will fit the mold of what an astronaut is, because Kelly and many of the astronauts, when they come and talk and try to inspire people are truly passionate about what they do. But something that has a broad application and a broad sweep of skills, you’re finding this, being an astronaut, being a CHAPEA crew member, you need to do a lot of different things and as good as you are into your focus, having that broad sweep of application is something that I think is important, really, if you’re an astronaut or really for any career that I think that you would have particularly here at NASA, or anything in, in space flight. Wonderful hearing from Kelly. That was a excellent way to kick us off, but now let’s go to CHAPEA Mission Flight Engineer Ross Brockwell.

Ross Brockwell: Hello, this is Ross Brockwell, flight engineer for CHAPEA Mission 1. Some questions for Houston We Have a Podcast in January of 2024. So how’s everything going? It’s still going great, still having fun. Time is still flying. Sometimes it’s kind of a mix of slow moments, slow days, but fast weeks. So time overall is flying. It’s a lot like life back on Earth. “Tell us about some of the highlights of the activities and tasks of the last month.” So New Year’s was really fun. I think we talked about that a little bit before. It was a good moment for us, halfway through the mission. It was really neat to kind of imagine what it would really be like someday for the first group of humans to be on the other side of the Sun. Mission Day 200 was also a neat milestone.

So now more than halfway through, what do I miss about Earth that would be important and possible to develop for Mars? Well, I definitely miss sunlight, natural light. I miss a view, I miss open movement. I miss running a lot. I miss vegetation and water features. It’s really kind of been fun to think about how to incorporate some of those things into a habitat design on Mars, it would be interesting to do things with kind of a multipurpose angle. Water, for example, can be used to shield from radiation, so it’s kind of fun to think about maybe having a portion of the habitat with a water reservoir above you. You know, maybe it’s sealed from the rest of the habitat just as a contingency, but it would have some amount of natural light coming through, and also some radiation protection, and also be a water source, you know, with some pressure from the elevation. So some useful hydrostatic pressure. So things like that are fun. It’s fun to think about building into the Martian landscape and having the protection, but also a bit more open space. Having some vegetation and water in the habitat that’s open to you would be pretty neat. A lot of positive, practical reasons, but also aesthetic and psychological bonuses. I’ve been thinking about animals too. I miss kind of animals and pets, and it’s funny to wonder how a dog or a cat would do in one-third gravity.

Do I think living in CHAPEA will influence the way I interact with people in my work, in my next job or my life? Yeah, definitely. I think I can easily say this experience will have a big impact on the rest of my life. Some parts of it are as I expected and as I’d hoped. Some of the challenges will be very good experiences when this is over. I still have several months to go, so I’m sure there’ll be more a lot of the things, you already kind of know, but doing something like this reinforces it highlights things and teaches you some of the nuance about how to appreciate the little things while you remember the big picture. You can do both. They can reinforce each other and how important it is to work as a team to appreciate and build on each other’s strengths and each other’s quirks. Also how being sure the fundamentals are covered affords you the time and energy to explore, be creative, try new things, have fun. You know, time flies certainly reinforcing that kind of no matter what your circumstances, it tends to, if you are working towards something and it’s around your interest and time certainly flies, but also just to always try to have fun and try to continuously learn.

Ross Brockwell: For the Artemis generation, what are my suggestions for courses students should take in high school? I think a well-rounded education is extremely important. Math and science are fundamental, so I would definitely encourage people not to shy away from them. I think anyone can learn anything, especially with an insightful and patient teacher. And math and science can underpin so many other things that it’s critical to have a baseline exposure to them. But also just to read as much as you can. I think that systems engineering and ecology are going to be very important in the future. And, you know, they’re now of course, but I think studying them at a young age will help you approach the things you work on in your life with a certain systemic understanding. An ecological understanding that I think is critical and sadly is absent from a lot of things we do in human endeavor. But I think that they would be good for people to study. I also think languages are good for people to study for the way your brain works, the way you understand things, but obviously also for culture and travel and international cooperation. Just confidence and perspective. I would say that everyone young should study multiple languages if they can, too.

“What’s coming up in the next month?” So we have a drone and rover mission coming up, which they’re always awesome. They’re fun. I’m going to try to finish a couple of the training things I’ve got on my plate that I’m looking forward to. I got a bunch of books to read. We’ve been talking recently about The Last of Us video game we’re going to kind of play as a group. It’s fun to do that, try and solve the puzzles and experience it. It’s a pretty good game. Pretty fun to play that way. So I’m looking forward to that. We’ve got a 3D print project going on that’s interesting. It’s coming together. I’m sure there’ll be some new EVA challenges to face that will be interesting and a couple of mission milestones coming up here in the second half. So I’m looking forward to all of that. So thanks again and looking forward to next month’s questions.

Host: Again, that was Ross Brockwell, flight engineer. Ross’s theme, I guess for some of the things that he’s thinking about is definitely around nature. Some of the things missing being the sunlight and outdoors. And I love his suggestions for how to improve the habitat, thinking about introducing nature into the habitat with definitely some aesthetic things, but the practical perspective of using water, not only as radiation shielding, but I don’t know if you’ve ever been to an aquarium and walked into one of the tunnels where the aquarium is above you. I was sort of imagining that when he was describing water being above as radiation protection, I thought that was a really good idea. Not bad having a habitat pet either, whether it’s a cat or a dog, not only just to have that, that company, but something to take care of and that maybe there’s some psychological improvement. For anyone that does have pets, you can definitely see the benefit of having something to care for in the habitat. So certainly a good suggestion.

But what’s great about hearing from Ross is his positive attitude. Just taking his approach to the halfway point and his approach to the mission. A lot of the things he was suggesting on how to think and what he’s thinking of at this point in the mission, all just positive. And I think it’s a reflection of really what everyone in the crew is feeling as well. No secret though, that if you want to be an astronaut and be a part of this math, science, reading, language, that round skillset seems to be a theme between Kelly and Ross so far.

Okay. Of course, as usual, we have two more crew members to hit, but before we do, we’re going to first pause and take a moment to speak with Brian Crucian and Satish Mehta about the immunology and virology component of CHAPEA. Here we go.

Brian and Satish, thank you so much for coming on Houston We Have a Podcast. It’s a pleasure to have both of you.

Satish Mehta: Thank you.

Brian Crucian: Thank you very much.

Host: Alright. Now, we’re going to be talking about immunology and virology. But Brian, why don’t we start with you? We’ve had you on five and a half years ago to talk about one of the hazards of human spaceflight. We talked very much from an immunology perspective. Can you talk a little bit about yourself and a little bit about immunology and what you do?

Brian Crucian: Well, Dr. Mehta and I are still here.

Host: Been here a while, right?

Brian Crucian: Still trying to ascertain the status of the immune system in the astronauts. And through a series of flight studies, we’ve published a lot of articles characterizing that, trying to figure out if that is a clinical risk for deep space missions. And that’s been largely successful. And so we’re now working towards countermeasures for deep space missions. How do we rectify the problem, restore immune function, and protect the astronauts? And that gets into the basic function of CHAPEA as an analog and as a validation of a countermeasure.

Host: Understood. Okay. Now, Satish, you work very closely with Brian, and you have a history with virology specifically.

Satish Mehta: That’s right. Brian and I, we have been working for the last, I would say, two and a half decades, or maybe close to three. I have been here, you know, for more than three decades here at Johnson Space Center working virology part. So virology is very important aspect. It actually is supposed to be a very good early biomarker for looking at immunity. So that is why immunology and virology, they’re very closely related and that’s what we have been doing, tracing viruses, Herpes viruses in astronauts, you know, starting from shuttle days to ISS and then to space analogs and CHAPEA and whatnot. You know, we have been tracing those analogs and spaceflight studies and looking at viruses, which actually have a very direct connection with immunology. If you have a good immune system, you know, your viruses, we all are infected with one or the other Herpes viruses. There are eight human Herpes viruses and all these Herpes viruses, you know, they infect one or another human being in that during one time or the other in their lifetime. So we all have one or the other RPS viruses, but we do not get sick. It’s because, you know, our immune system is working very well in our favor. So that’s what we have been doing for the last so many years.

Host: And you’ve been doing it together, right? You guys? You said in virology and immunology, you guys have been working in some capacity to understand this exact relationship, Satish, what’s happening in the immune system, what’s happening with the Herpes and how they’re related in terms of virology and spaceflight. You would think naturally, right, as me, as a layman, that once you’re in space, as long as you do your proper quarantining and go up into space, you’re not exposed to viruses. But you’re saying that this may not be the case, and so something we have to study closely?

Satish Mehta: You know, that’s a very good question. You know, these viruses, it’s not only these viruses coming from outside, we all have these viruses. When astronauts go up in space, you know, they carry these viruses up in space. Now it is the function of the immune system to keep these viruses under check. If the immune system is good, you know, and if the immune system is able to keep these viruses in the latent condition, in the checked position, you know, where they do not cause a problem, they’re fine. But unfortunately, that doesn’t happen. So we all know for the last, 20, 30 years of studies in the immune system, we all know the immune system does change. It actually got depressed, you know, maybe momentarily, but that is what, you know, when the immune system goes down these viruses, you know, who had been under check off an intact immune system, these viruses flare up, they start to replicate more in number. And that is a problem. So that is what we have seen in our earlier spaceflight studies. That immune system goes down, it actually dips down and the viruses go up. But when they come down on the Earth, you know, this, as I said, it’s a very transitory change. So immune system comes back and the viruses again come back to their normal status. So that is how you know, they are related with one another very closely.

Host: Yeah. And this helps, this is part of the reason why studying this for such a long time helps us to have such a better understanding. Brian, you know, a lot of what Satish was mentioning is the spaceflight application. So understanding and studying humans that actually fly to space on long-duration missions, International Space Station missions. He also mentions some analogs. So when you combine some of our knowledge of working with astronauts and understanding some of these effects with the dip in the immune system only to come back upon recovery back on Earth and studying that with astronauts. And then also in analog missions, what do we know so far? What is the landscape of immunology as we know it today?

Brian Crucian: We can take a blood sample from you and pull the immune cells out of your blood and evaluate your immune status. Are those cells working right? Is there inflammation? Are they able to mount a defense against a pathogen? We have a variety of cell culture assays and microscopy, assays, they answer that question. But the virology is important because when we see diminished immunity, we’re not sure if that’s really a clinical risk to you or not. It can happen transiently anytime someone is stressed. But when we see the latent viruses react at the same time, that tells us that we’ve got a clinically relevant immune suppression and points us towards a need for countermeasures. And so that swings back to the analog question. I have a variety of countermeasures I want to test that could be nutritional exercise, stress relieving techniques.

And so how do I test that? Well, the best place on Earth—pun intended—is a ground-based space analog to start, because it’s expensive to take something to flight, and it’s nice to triage things on the ground before you take them to flight. Finding the best-spaced analog is the relevant question. Head down tilt bedrest is great for bone and muscle loss, but it’s not really good for immune because you don’t really recreate those stressors associated with spaceflight, the circadian issues and all the things we think work to suppress the immune system. And so an analog like CHAPEA, where you put people in a high fidelity simulated vehicle for a year-long duration, we think might be an attractive analog to test immune countermeasures.

Host:S o let’s dive into countermeasures for a minute because you talked about, okay, we have some understanding. So what are the countermeasures that we can implement with analogs that you’ve used in the past, in terms of looking at from virology and immunology? What are some of the considerations on what you think might be a good countermeasure to combating this dip in immune response?

Brian Crucian: That’s another good question. And the good news for ISS astronauts is that some of the countermeasures we’ve already put on orbit have been effective at improving immune status. And there’s some evidence to suggest that aerobic exercise, resistive exercise, increased durations and loads have been particularly effective. Construction era crews, compared to more recent crews, we definitely see an improvement. The bad news for deep space missions is a lot of those countermeasures as they’re currently constituted, don’t translate well to deep space where the habitable volume is less, there are power considerations, less frequent resupply, et cetera. So we need a countermeasure specific for deep space missions.

Host: That’s perfect. Yeah, and what you just talked about was not only the countermeasures but introducing a lot of those stressors, which are, I think, more unique to CHAPEA. Satish, we’ll go to you. Can you talk about when CHAPEA actually started coming into the conversation and you worked with Brian to say, hey, this is something we should be a part of, and let’s start working and formulating what this experiment design is going to look like from an immunology and virology perspective?

Satish Mehta: You know, as Brian mentioned, there are a lot of different analogs. And the problem with every analog is, you know, so there is one or the other item missing, which would mimic the space program or the spaceflight. So having a long duration like CHAPEA for one year, you know, it was a very attractive thing, you know, so they are in a closed environment and they are getting exposed to all kinds of things as happens to astronauts during international spaceflight. So that was a very attractive thing for us, you know, to test how the immune system would behave for that one year of duration with all the countermeasures being introduced. So that is why we wanted to take a look at that, you know, how these subjects who are in CHAPEA would respond to the countermeasures that have been subjected to.

And, again, you know, from looking at the virus point of view, you need to make sure this immune system is good enough to control those viruses which do not produce any problems later on in this stressful environment. So, I think one of the things we do need to mention over here is stress. You know, we have been talking a lot of these things. Stress really plays a very important role. And we do, in our immunology lab, we do measure stress markers. So they are like stress hormones. So cortisol, DHEA, salivary amylase, cytokines, you know, some of those things are very directly related, very much directly related to stress. And the way it works, you know, we actually have a model in the lab that shows, you know, how stress controls the release of stress hormones through HPA and sympathetic nervous system, and they produce these hormones, you know, to the larger quantity in an environment which is not normal.

You know, so like, you know, when we are sitting in a room and, you know, having a very common conversation that is a different, you know, for maybe an hour or two, but once you are there in a close environment for a period of one year, things are not the same. Right? So that is how your hormones start to behave differently, and they start to get produced in larger quantities, which would impact the immune system, larger quantity of the stress hormones, again suppress the immune system. And again, you know, as we just mentioned a minute ago, suppressed immune system does let these viruses release in the system more, and they start to replicate, they start to reproduce more and more. And that is how we actually try to connect these three things: stress hormones, viruses and immune system.

Host: Now, of course, for a ground-based analog, you talked about the benefits of CHAPEA, you can introduce quite a number of stressors into a ground-based analog. But that’s a ground-based analog is getting very close to the real thing, right? Real deep space flight going on a mission to Mars and the altered gravity fields and all of that. So of course, when you are looking at an analog, you get most of the stressors, a lot of the stressors, but not all of the stressors. So when you’re analyzing and coming up with an interpretation of the data on these are the stressors that are a part of this, but then trying to come up with the best model for what you predict would be as part of that actual spaceflight, when you have the entirety of the stressors. How do you properly analyze the data to come up with a good analysis of this is the right mix of countermeasures that we think is going to work to help the immune system?

Brian Crucian: So in looking at possible ground analogs, the field deployment ones, Antarctica, NEEMO are attractive because they’re actual missions, but you have less control over them. There’s so much from shipping to getting bios samples collected to how you’re going to do your immediate processing. That remains a challenge. Something like CHAPEA is right next to the laboratories and you have much better control. And Dr. Douglas, the PI, has designed a study that can be conducted in a very integrated fashion. You can look at all the different aspects of physiology, including immunology and virology, coordinate that with the diet The crews are receiving the exercise loads, and you can look at all of this in concert, which really helps clinical interpretation of the results. Our ultimate customer is the NASA flight surgeon. This is the person that we’re generating this data for, who’s ultimately responsible for caring for the deep space crews. And so we try and answer this question for them, and it will guide the medications they may use or may carry on these missions, and how they’ll ultimately care for the deep space crew members.

Host: That is perfect. Yeah. I never really thought about that. And I guess that’s true for a lot, but the flight surgeon is, and this is the benefit of CHAPEA, is not the ultimate customer for everybody. Right? Of course, you have the food scientists that have to think about the right mix of what a food complement will look like, the nutritionist, right? But they’re all going to inform what it needs to support. It sounds like it’s the support folks for the astronauts and the support folks for the mission from a human perspective.

Brian Crucian: No countermeasure acts on one system, right? All of these countermeasures are translational. And so we’re working with the exercise people, the microbiology people, the nutrition laboratory food, to, to look at the effects of each countermeasure broad scale on the entire, on the entire organ system of the body.

Host: I suppose if you were to look at just immunology and virology and design something that was very isolated into that narrow scope, it wouldn’t give you the data that you want. To have an integrated approach and to consider all the different factors gives you better data to work with because it’s more representative of what the actual spaceflight is going to be.

Satish Mehta: Yeah. All analogs, as we just talked about, you know, they’re different from one another. I mean, one of the biggest thing which is missing in every analog on ground is the gravity, right? So whichever analog we have or we try to use, Antarctic actually had been for many of our immune studies, we have done, you know, it has been very closely associated. It has been very closely related with some of the data we have gotten in terms of immune changes. But again, as you know, Brian mentioned, we do not have that much control, it’s not only the sample shipping supplies and getting samples back even over there, you know, it’s very difficult. You know, how to have those subjects comply with the requirements so they’re very far off. So unlike that, we have a little better control or a little better access, you know, to the subjects in CHAPEA and which analog works better for which studies. It’s a very different thing. Viruses as, again, I’ll bring back to you to viruses, it’s a very sensitive indicator. It’s a very sensitive indicator of changes in immunity. So what I mean is with a little bit change in stress from normalcy, these viruses start to react and produce more in quantity.

Okay. So, you know, it again, depends upon what kind of stressors or what kind of analog we are looking at. Say for example, bed rest, you know, we have done studies in bed rest, we have seen changes, and, you know, the amount of viruses they replicate or the load that gets replicated in bed rest studies is much less as compared to Antarctica study, you know, which is very far off, temperature is very harsh, it’s very different. So all those things, you know, again, you know, if we are able to detect any viruses, any Herpes viruses going up in quantity, and that is a very good indicator that there are changes in the immune system, even if they come back to normal, you know, once that stressor is removed.

Host: Right. Yeah, cause you said the relationship is so tight that if you see changes in the virology, it probably means the immune system has been suppressed. And you said the sensitivity to stressor is a very close indicator. And it is very sensitive. And that’s the interesting thing. I think when it comes to a study like CHAPEA, an analog like CHAPEA, what it sounds like is introducing the most representative stressors is that much more important for your fields. If you don’t have the right stressors, you won’t get as good data to understand what is happening to the immune system.

Brian Crucian: Our work has shown that there’s a continuum of stress and then immune compromise and then clinical disease. And you can line up all of these analogs and the different aspects of spaceflight—shuttle missions, construction-era ISS, current ISS—on this continuum and you can also put terrestrial situations—med students taking exams, bereavement—all fall on this continuum, where at first you’ll be stressed and we can detect that in by our assay stress hormones. Then there’ll be some degree of immune compromise resulting from the stress hormones. And if it persists, if the stress increases, eventually there’ll be some immune compromise that results in latent virus reactivation that will at first be subclinical. And in extreme situations that latent virus reactivation progresses to disease. And that’s what shingles is.

Host: Ah, really it’s that latent virus activating. Is that some of your work?

Satish Mehta: Yeah, actually, when we started to do these viruses looking at these viruses in spaceflight, it was a very strange question to be posed for astronauts in this space environment. As a matter of fact, you know, I actually was asked many a times why viruses? What viruses have to do at NASA?

Host: Right. That was my first question.

Satish Mehta: Right. It’s a very good question. It’s a very obvious question, you know, and we have looked at that, again, I said for a long period of time, we have seen that. And it does. So the first thing we wanted to see, you know, if these viruses even reactivate, just let me take you back for one minute. You know, not giving a lecture on viruses, but in just maybe 30 seconds, these viruses are sitting in our body in different parts of the body, in different cells of the body producing no problem, producing no harm. We all have these viruses and everyone is fine. So for example, you know, we all had the chickenpox, you know, when we were little, maybe, you know, if not chickenpox directly, you got a vaccine. So chickenpox is caused by one of these Herpes viruses. It’s very similar as zoster virus. So you have chicken box at the age of maybe two months or three months, and you feel fine after a couple of weeks of little bad time. And now you’re 50 years off of age, 60 years, you know, during that time you don’t even remember that you ever had chickenpox until I just maybe mentioned to you, right? But your body always remembers that that virus is always sitting in your body. It’s in the dorsal root ganglion, it’s in the spinal cord. It stays there for the rest of your life without causing any problem until a stressful event happens. Until your immune system goes down, until any of these, you know, abrupt thing happens, you know, which is not normal. And when that thing happens, the same virus which is sitting in your nerve for the last 50 years will reactivate, will wake up, start to reproduce more and more viruses replicate and travel through the same nerve and come out in the skin and produce shingles.

And shingles, those who have had it, you know, can tell you it’s not a fun disease. It’s a very painful disease. It can happen in any part of your body through those, you know, dorsal root ganglions, you know, and that is what we have. We were very much worried about that for astronauts, you know, that virus is there, that virus, as I said, you know, these astronauts take that same virus, varicella-zoster virus in space when they go up in there and in space, you know, the things change a lot. There is no gravity, radiations are too high in international space flight system. Food is different. The kind of environment they live in, stress is high. Again, you know how a person perceives the stress is different. But all those things, they affect these viruses and it can happen that viruses replicate to produce a symptom.

That is what we have actually seen recently in one of our astronauts and the studies and review. And we don’t want to reveal too many things, you know, until it comes out. We have seen that viruses producing clinical conditions in stressful environment with the immune system going down again, you know, that the triangle is always very important. Stress hormones, immune system, and viruses and viruses is the ultimate clinical outcome of changes in immunity and increase in stress hormones.

Brian Crucian: Yeah. And there are a number of different adverse clinical outcomes we’re worried about related to immune compromise. But the virus questions particularly important because we all have them and we’re carrying them with us to the Moon and the planets beyond. You cannot screen these out with a pre-flight quarantine. It’s one of the few things that quarantine will not be effective against.

Host: Cause it’s always with us. As you guys are talking, you both seem like very calm individuals. I think you both understand the risk of a stressful environment. Meanwhile, you’re talking about it could activate with a little bit of stress. And I’m over here getting all antsy, getting more stressed and just trying to breathe. Cause it sounds like what you need is an environment that is conducive to reducing that stress, which is interesting for CHAPEA, right? Cause CHAPEA is introducing the different stressors. This is part of it and I wonder if, you know, one of the things you talked about in terms of stress for CHAPEA, and I wonder if this is related to your study in immunology and virology, is the length of the study, just over time. Is one of the things you are interested in to see if the stress increases over time, as subjects continue to be in a confined environment and see if maybe there’s a consistent stress over a long period of time, maybe towards the back end of a mission, as folks are hoping, you know, heading towards the end, is that one of the more interesting factors of CHAPEA from an immunology and virology perspective?

Brian Crucian: Yeah, exactly. The duration is extremely important, because it is a safe laboratory environment and the crews know that, and we need to stress them out to make it just as bad as it is for astronauts. And so how you do that is increasing the duration and increasing the fidelity. Want to make it look like a real vehicle, a real planetary habitat. Introduce those communication delays and all those other little nuances that increase stress as it does for the astronauts. But the duration’s extremely important because there’s a kinetics of adaptation to any environment. And if we were to sample astronauts a few days after launch, all we’re really looking at is post-launch stress and adaptation. And so when we sample the astronauts, we wanted to have been enough months into the mission that we’re looking at what we call “space normal.” We want to define how you’re going to be in that months or years long duration to the Moon or Mars. And so same thing for CHAPEA. You want to increase the duration of the mission sufficient that you see how stress and immunity and all the other physiological adaptations settle out to, into what is going to be normal in that environment. And that’s what we want to measure. And then if it looks like flight, that’s what we want to test a countermeasure for.

Host: Okay. Alright. Very good. And last question relates—

Satish Mehta: Can I say something here?

Host: No. No, I’m kidding.

[Laughs]

Satish Mehta: I just want to add the duration is so important. You know, a long time ago when it was a space shuttle thing, only couple of weeks, astronauts go up and come down. And we saw these changes and this was one of the understanding of people over here at NASA that maybe, they go up in space and it’s like an acute change from normal environment to an abnormal space environment. And then they come back, you know, all those changes we have seen, or we had seen in the space shuttle studies, maybe after we have International Space Station, and when these astronauts go there for a longer period of time, they get acclimatized and all these changes will go away. So all of a sudden, you know, you are given a shock of zero gravity, increased radiation, food is different, people you’re interacting are different. So that actually is an acute change. But you know, when the space shuttle went away and we started studies for long duration spaceflight, which were few months four, five, six, seven, eight months, you know, maybe that thing go away. It didn’t go away. We actually saw more changes. As a matter of fact, you know, we have seen worse change in immunology, immunology as well as in virology.

So as the duration, you know, even going to Mars, you know, all those changes, we actually have published these papers, these changes or these problems do not go away as we have longer duration, immunology is going to be something we still have to monitor, you know, and with immunology comes all paraphernalia of things like viruses and immunology related diseases also. So I think it’s very important to study immunology in the long duration studies, whatever we can do. So CHAPEA actually contributes a very significant role in studying immunology and virology for a longer period of time and how these changes happen and how we can even control them with intervention of the countermeasures.

Host: I just found it interesting that it didn’t sound like it was initially apparent that the duration would be an additional stressor. It sounded like, I don’t know if you were hypothesizing no change, or maybe that because the pace of a short duration mission was intense, that that is enough stress, and over time, maybe their workload would decrease, and maybe you were hypothesizing that that would then decrease stress.

Satish Mehta: I’ll add one more thing here. You know, we did a study long time back in Antarctica. And one of the attractive thing of doing studies in Antarctica is, or was, it’s a long-duration study and all these changes as we have been talking for some time we saw in Antarctica. But the interesting thing was, you know, close to the time when they were going into Antarctica was very interesting. That is where we saw the biggest change in viruses. You know, when they go into Antarctica, so these viruses, they really flare up in larger quantity and when they’re close to be coming out, so they started to feel a little bit maybe less stressed or maybe less worried, okay, now there’s only one week left, two weeks left. And we started to see less changes there. Those kinds of studies, it all is related with how you perceive stress, how your mind thinks about, you know, a good thing is coming in, so we don’t need to worry about that, so virus is also starts settling down.

Brian Crucian: Yeah, we published a case study of an ISS astronaut that had dermatitis issues related to the immune and viral problem. And we were able to line up disease flares with dockings, undocking’s, circadian shifts, other significant mission stressors. And it basically correlated, meaning that stress is a granular thing. Spaceflight is a chronic stress with overlaid acute stressors that occur. And that’s where we see our issues and it information like that can help them mission planners, design the missions to be less stressful and reduce clinical risks.

Host: And whether it’s a winter over in Antarctica or whether it’s an ISS mission, the length of time helps you to find those acute moments. Excellent. Alright, last question is on just having, and this particular analog study, CHAPEA, we’re talking about the benefits of this, the length of time, but I’m sure you, like many others, are working with this subject of four, but it’s a relatively small sample size. So the benefit of repeating a study like this so you get more and more samples from your perspective, is that something that you’re looking forward to?

Brian Crucian: Yeah, and the reason is obviously you want to increase the sample size. Eight subjects is more meaningful than four, 12 is more meaningful yet. But also we’ve learned from our Antarctica work, each mission can be different in terms of the personalities of the crew, how they handle and react to stress and the types of relationships that they form as they problem solve together during the mission. And so the missions can be very different and so multiple missions is extremely important for interpreting the science findings.

Host: Wonderful. And you are not def definitely not the only scientist and researchers looking forward to continued research. It’s a wonderful study and I enjoy talking with folks like yourself to really dive into how integrated and important a study like this is. So Brian and Satish, thank you so much for coming on Houston We Have a Podcast. It’s absolutely fascinating just to learn about the worlds that you’re in and how in incredibly interesting it is and holistic and how it contributes to our overall understanding of deep space missions. Thank you for taking the time.

Satish Mehta: Well, that’s great. You know, I mean you can see, we are all excited. We are very passionate about what we do. You know, once we start talking about our stories, they never end. Thank you.

Host: I was locked in. It was awesome.

Brian Crucian: We have this wonderful analog for science purposes and thanks for having us.

Host: Absolutely.

Satish Mehta: Yeah. Thank you.

Host: Alright, that was a great conversation with Brian and Satish. Two more audio logs to go. Let’s first start with Medical Officer Nathan Jones.

Nathan Jones: Hello, my name’s Nate Jones. I’m the medical officer for CHAPEA Mission 1. Since we last checked in, we celebrated New Year’s Eve, which was also the halfway point of the mission. This month we celebrated Mission Day 200. Those were probably the highlights for us. Unfortunately, all the real fun places to celebrate the new year on Mars were all booked up. So instead of going out, we stayed in and ate a special meal. We also watched a movie together to celebrate the new year and I think three out of the four of us actually fell asleep during the movie. So we decided to celebrate the new year a little ahead of Houston. We ended up putting on cone hats and took a few moments to commemorate the new year as a crew. We called it a night not too long after that and for day 200, it was basically any other day in the hab, other than the fact that we had a small celebration at the end of the day.

Regarding things on Earth that we would want to be given priority for development on Mars, we had an interesting discussion the other day around that exact question. It was sort of at what point would you want to start putting other types of buildings on Mars. For instance, when you put in a building solely for recreation, when you think it would be a good idea to put in places to shop? There are things that I think probably ought to come first. For one, I know I miss being out in nature, so I think in order to help prevent people from being homesick, it would be important to find ways to recreate a lot of the feeling of being in nature. Astronauts I’ve often heard quoted as saying they missed the wind and the smells of Earth. And so I think it would be possible to recreate a lot of the sensory of being in nature on Mars. So that’s something I think we should do. For instance, you could start with virtual reality, but I think it’d be a good idea to develop something that feels like grass, maybe actually grow grass there or have sand that you can have in your toes, a varying breeze, the smell of dirt, plants, dew. Then one that I think would be big for me is the feeling of radiant heat on the skin. And I don’t think that would be too hard to replicate.

I was also asked if the CHAPEA mission would influence how I interact with people at work after the mission. I’ve actually been reading a lot of books on leadership and so I hope to take a lot of those lessons and skills back with me to Earth. I also think that the soft skills such as better communication will be helpful in the ER as well.

Nathan Jones: Another question I was asked is what suggestions I might have for courses for students to take in high school. I think students should focus on whatever interests the most. If you focus on things that you can pursue a passion, the work you do will just be that much better. Yes, scientists will still be needed in the future. We’re going to need all the STEM professions for sure, but I think the Moon and Mars will also need people like artists. There is no way someone is going to make it on the Moon for 378 days without books, music, and entertainment. So find what you’re passionate about and pursue it and find ways to apply it.

What’s coming up in the next month? Well, first thing that I can think of is Groundhog Day. We actually watch the movie at one point and joke that it sometimes feels like Groundhog Day in the hab, we’re going to also hit the three-fifths point of the mission next month. And so we’ve got another milestone already coming up and after that we get to see how Valentine’s Day goes whenever you’re 250 million miles away from your significant other. I know I prepared something for my wife at home and I’m hoping it works out better than my anniversary plans worked out, but we’ll see. That’s it for now. I hope you all enjoy the update.

Host: Alright, again, that was Medical Officer Nathan Jones really appreciated his dry sense of humor in this one. I locked into his description of things, you know, one of the first elements to bring to improve the habitat. He was approaching it from a very futuristic perspective of Mars with shopping and recreation. So he was really thinking about the holistic view. You know, if we had everything, what was probably be the first thing we would want, matching Ross’s theme of nature. But also I guess not just from the perspective of missing nature or wanting to be in nature, but really those sensory elements, the feel of the grass, the smell of the dew. Very interesting to hear some of the things that are missed as they’re in the habitat. Groundhog Day seems to be a pretty funny reference as well. Kelly mentioned it in her audio log, just having the repetitive task. But it is true that being on Mars, there’s going to be a lot of those same tasks that are necessary for day-to-day life. So I’m glad that they’re embracing it with a dry sense of humor and still getting along great as a crew. Alright, last but not least, here’s Science Officer Anca Selariu.

Anca Selariu: Hello Earthlings. I am Anca Selariu, science officer of CHAPEA Mission 1. You are asking how is everything going well overall, the mission is going very well and we are collecting massive amounts of data. I feel that time goes by very fast, especially now that we pass the halfway point. There’s always a lot to do and a lot to learn across self-assigned tasks and mission control-assigned activities. So it is very hard for me to ever get bored. In fact, I don’t think that has ever happened to me here. Besides interacting with the other crew members is always a source of interesting knowledge and fresh perspective and quite a lot of entertainment.

Some of the highlights of the tasks of the last month, well, we entered the new year in great spirits because now we are in the year we get to see our friends and family again. But we spent a great portion of the past month simulating communication blackout, which is a critical scenario to train for when preparing to live on Mars, especially during its conjunction with the Sun or losing communications for any other reason. Humans have not yet experienced complete loss of communication with human space travelers for days at a time or even weeks. And for ground control, even minutes probably feel like an eternity. For Mars missions, both astronauts and mission control have no choice but to be comfortable with periodic loss of communication. So this is an extremely interesting experience for me.

Now that we’re halfway through, what do I miss most about Earth? Well, what took me by surprise was how much I miss Earth life. Its sounds, its colors, it’s almost a visceral sensation, much like a phantom limb syndrome. I really never thought that this was possible. I miss the greenery, I’m missing an insect, petting a cat, hearing a bird. I miss the colorful sky of Earth. It’s ever-changing weather. I miss the nearly infinite library of Earth’s nature smells. So for me, what is important and possible to develop from ours? Of course, it is important to ensure the safety and cover the long-term basic survival needs for humans. But knowing what I know now, I don’t think that I would want to travel that far without our fellow Earthlings from other species. And I believe focusing on robust life support systems for the non-human crew like crops and hydroponics is well worth the effort.

Anca Selariu: Do I think living in CHAPEA will influence the way I interact with people in my work or next job? Well, I think CHAPEA will always influence everything in my life from now on personally and professionally. Here on Mars, Dune Alpha, you get to experience human interaction dynamics in a controlled environment and you realize that even 1% of the same objective reality, everyone processes it and responds to it slightly differently. This way we complement each other’s experience while still united under the same vision and pursuing the same mission objectives. This diversity of skill, experience, and perspective, as well as respect and openness to each other’s input, is really what constitutes the strength of our team. And the same is true for society at large.

For the Artemis generation, my suggestion for courses that students should take in high school? That’s a very interesting question. I think students should take full advantage of anything they’re offered and pursue everything that they’re passionate about. They should truly cherish the diversity of knowledge they’re exposed to in high school because they may not have that opportunity again. There’s nothing one learns that is superfluous. Everything sciences and humanities alike can prepare young human brains for the complexity of our rapidly changing world. Of course, it is critical to build a solid science foundation and be able to use a clean language of mathematics to describe the natural world so elegantly as we have. It is ideal to understand how living and non-living systems are built and evolve, but is also important to understand how your own brain works as you navigate the mysteries surrounding our existence and how to keep an open and curious mind, how to accept and live with uncertainties and navigate with imperfect tools while trusting others and trying to make the best decisions as you move along.

What is coming up in the next month? Well, we anticipate several new EVAs and I always enjoy being out on the Martian surface. Also, we should have a few more drone and rover missions and collect more geology samples and study them and hopefully successfully germinate a new type of plant in the Martian soil simulant. So, we’ll keep you up to speed and in the meantime, stay positive and continue dreaming of Mars. And thank you for all of your support.

[Music]

Host: Again, that was Science Officer Anca Selariu. A theme I guess across all of the crew members, they all have this sense of missing Earth and some of the features that it has. Anca focusing mostly on life and people, and an appreciation for everything the Earth has to offer. So I feel like when designing a habitat, something for future habitat designers of Martian shelters will probably have some level of influence from the CHAPEA crew, considering how to bring Earth, how to bring Earth elements into the habitat. You know, I thought Anca had some beautiful words about learning a lot, and I think it’s true, not just in their words, but in their actions. Even ahead of the mission, we were learning about some of the things that they were bringing, some of the things that they were looking forward to doing, not only to support the mission, but really in their free time. All of them have a sense of continue learning, whether it be reading or studying a new thing, learning a new language or a new skill, like guitar. A lot of them approach this mission with an opportunity to continue to learn. And I think as we hear from all of the crew members on how to be a crew member and how to pursue something that you love, including in math and science, I think that lifelong passion for learning is something that is also necessary for anyone that wants to go into this field. Well, that’s it from the crew, from Audio Log #7 from Dune Alpha. Thanks for sticking around. I hope you’re enjoying the Crew’s journey. This is the seventh audio log in our series. You can tune in once a month to check in on the crew.

Maybe you’re inspired by the crew and would like to be a part of an analog like this. If you are interested and think you have what it takes to take on this year-long challenge and contribute to our understanding of what it will take to support human missions to Mars, applications for the next mission, CHAPEA Mission 2, are open. Head to chapea.nasa.gov to fill out an application and become a Mars analog crew member. Applications are due April 2, 2024.

Check nasa.gov for the latest happening across the agency and you can check out us and many of the other NASA podcasts at nasa.gov/podcasts. If you want to talk to us on social media, we’re on the NASA Johnson Space Center pages of Facebook, X, and Instagram. Use #AskNASA on your favorite platform to submit your idea, and make sure to mention it’s for us at Houston We Have a Podcast.

Recordings were sent from the CHAPEA crew through January and we had the conversation with Brian and Satish on February 2, 2024. Thanks to Will Flato, Dane Turner, Abby Graf, Jaden Jennings, Dominique Crespo, and Anna Schneider. Thanks to Brian Crucian and Satish Mehta for taking the time to come on the show. Thanks for Grace Douglas and Jennifer Miller for their efforts in reviewing these audio log episodes. And big thanks to Kelly Haston, Ross Brockwell, Nathan Jones, and Anca Selariu for sharing their experience for this audience on Houston We Have a Podcast. Give us a rating and feedback on whatever platform you’re listening to us on, and tell us what you think of our podcast. We’ll be back next week.