If you’re fascinated by the idea of humans traveling through space and curious about how that all works, you’ve come to the right place.

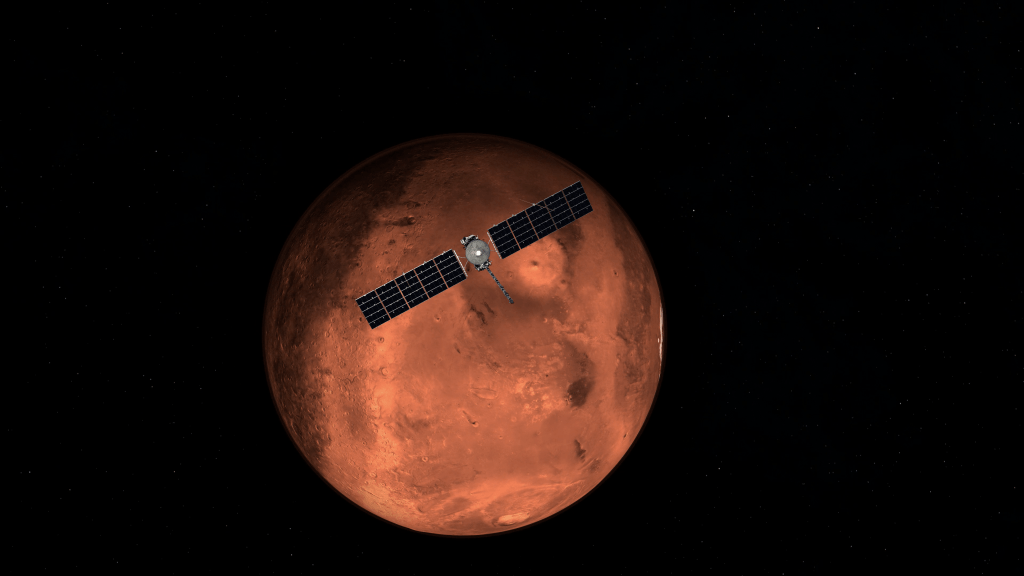

“Houston We Have a Podcast” is the official podcast of the NASA Johnson Space Center from Houston, Texas, home for NASA’s astronauts and Mission Control Center. Listen to the brightest minds of America’s space agency – astronauts, engineers, scientists and program leaders – discuss exciting topics in engineering, science and technology, sharing their personal stories and expertise on every aspect of human spaceflight. Learn more about how the work being done will help send humans forward to the Moon and on to Mars in the Artemis program.

On Episode 193, NASA and private industry leaders speak to the growing market in low-Earth orbit, the International Space Station, and the future of commercialization of space during a virtual roundtable recorded on November 18, 2020.

Transcript

Pat Ryan (Host): Houston, we have a podcast. Welcome to the official podcast of the NASA Johnson Space Center, Episode 193, “Expanding the Market in Low-Earth Orbit.” I’m Pat Ryan. On this podcast we talk with scientists, engineers, astronauts, all kinds of experts about their part in America’s space exploration program. Today we’re going to take you inside another important aspect of the mission of the International Space Station. From before the first element of the station was launched in 1998 through the arrival of Expedition 1 to begin a continuous human habitation of space that’s now in its 21st year, one of the International Space Station program’s primary goals has been to promote the commercialization of space: by creating a science laboratory in orbit, and by being a reliable destination for years and years, and yes, by providing seed money for private development. The station has provided a goal that private companies could drive toward, whether in making use of the facility for scientific research, or in delivering payloads, or in creating their own products–heck, creating their own companies–to help move private enterprise off of planet Earth. And it’s worked. This is the fourth in a series of NASA-sponsored panel discussions in recognition of the 20th anniversary of continuous human presence on the station. We brought you the first ones in February, March and early April. This time, representatives of NASA and several private companies discuss how the station has helped create a new era in space exploration. The moderator is NASA public affairs officer Gary Jordan, who you’ve heard here on the podcast from time to time. He will introduce you to eight guests gathered at a virtual roundtable to provide some background and perspective about the development of commercial space and their thoughts about the next steps. OK then, here we go.

[ Music]

Gary Jordan: Hello, everyone. Thank you for joining us for this next installment in our series of panels in celebration of the 20th anniversary of continuous human presence on the International Space Station. The station has been a critical test bed for scientific research and technology development in low-Earth orbit for the past two decades. By the time we reached 20 years of continuous human habitation, more than 3,000 experiments had been conducted involving 4,200 researchers from 108 countries. Truly an international orbiting laboratory. What is clear is that there is value in low-Earth orbit in the future of operations in low-Earth orbit lies with commercial companies. Commercial work done in low-Earth orbit is not new. NASA has had long standing relationships with commercial companies; in fact, many of our panelists today represent those very companies. The International Space Station will play a critical role in NASA’s goal to develop a robust economy of robust commercial economy in low-Earth orbit. So, on today’s panel titled “Expanding the Market in Low-Earth Orbit” we’re going to explore the history and future of the commercialization of low-Earth orbit with some of the most influential people leading these efforts. So, joining our esteemed panel today is Mike Read, International Space Station business and economic development manager at NASA; John Mulholland, vice president and manager for the International Space Station program at Boeing; Christine Kretz, vice president of programs and partnerships for the International Space Station, U.S. National Lab; Jeffrey Manber, chief executive officer and co-founder at Nanoracks; Rich Boling, vice president of corporate advancement at Techshot; Phil McAlister, director of commercial spaceflight at NASA; Benji Reed, senior director of human spaceflight at SpaceX; and Ven Feng, deputy manager of NASA’s Commercial Crew Program. Thank you all for taking the time to discuss this topic today. Mike Read, I want to start with you. Sort of setting the context for what we’re going to be talking about today. We talked about low-Earth orbit in my introduction, said that phrase quite a bit. But let’s start with that. What is low-Earth orbit? And what is special about that part of space for commercialization efforts?

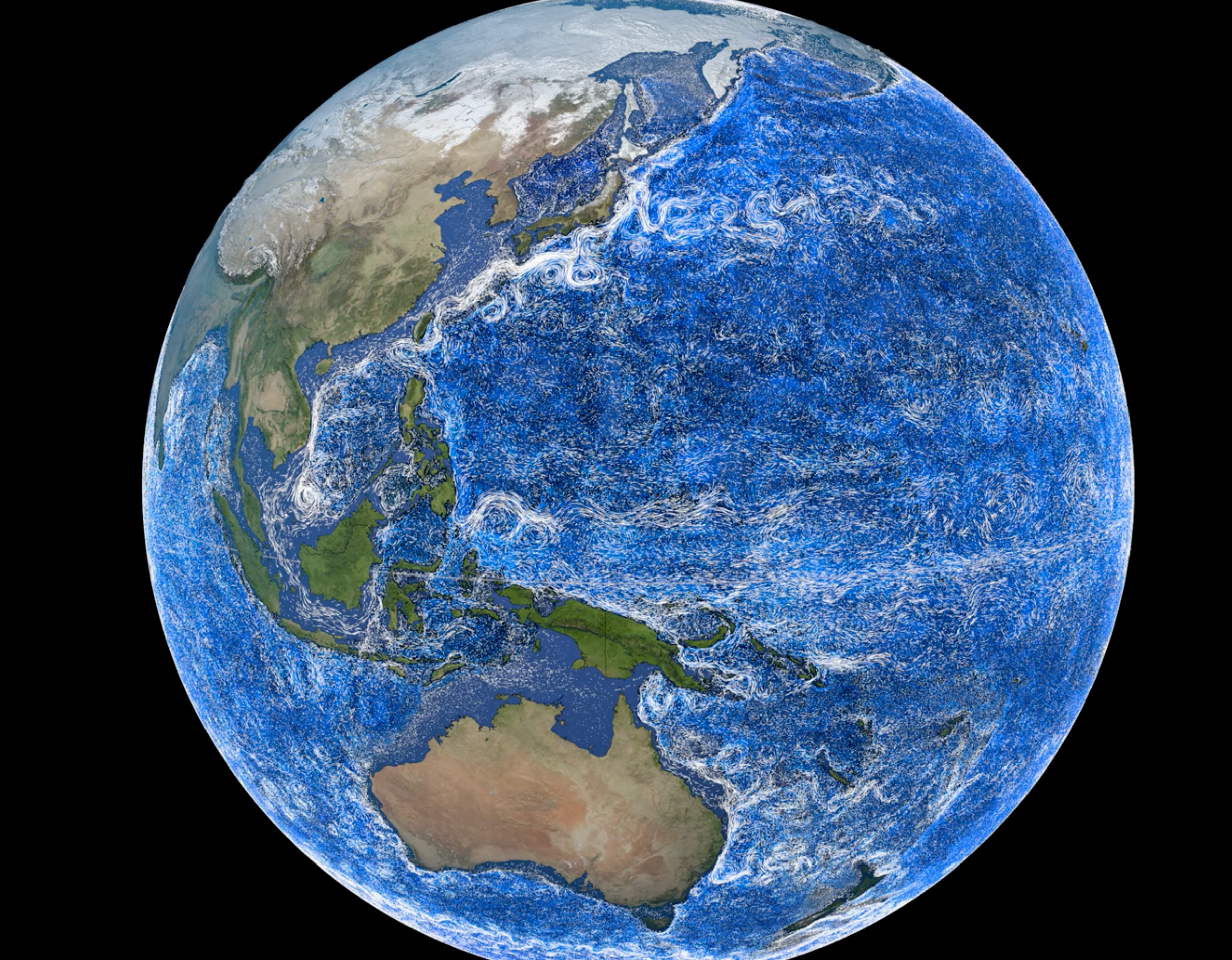

Mike Read: Low-Earth orbit, that’s what’s close to Earth. The closest to the Earth as opposed to geostationary, which is 22,000 miles away. This could be as close as 150 or 200 miles away. And that’s the orbit that space station’s in, about 250 miles. It’s quick to get to. It’s cheaper, relatively to get to than your deeper space orbits. And so, that’s — a platform that — where we have a space station where we do most of our research right now. It’s also very expensive to get platforms into a much deeper space positioning. And so therefore, access to it is more expensive and the volume is incredibly limited.

Gary Jordan: So, Mike, let’s talk about the International Space Station in particular. How is the International Space Station a player in some of these commercialization efforts? And then why is this commercialization effort, at all, important to NASA?

Mike Read: I’m going to start with the second question first, because the why you do something seems to me always to set the stage for the how. That — there’s a couple of truisms with regard to NASA and our need for space. One is NASA is always going to have a need for a low-Earth orbit platform, for crew proficiency and training, for our fundamental and applied research and critically for our advanced systems development, for our exploration program. Because things don’t operate in space the same way they do in 1 g. And until we’ve got years of operating in a low-Earth orbit platform with a next-gen system, we’re not going to put that in a deep space platform and trust it. But the second thing is space station is going to be the last U.S. government-funded, and 100%-led platform in LEO. It’s just — it’s not tenable. It’s not going to — there will not be another U.S, government LEO platform. And so, if we don’t use station right now to enable the development of not only the next generation platform, but the use of that platform, the supply side is critical for our LEO economy. You were working on our crew and cargo transportation, that’s been going on for well over a decade and others on this panel are going to discuss those. And more recently, we’ve also enabled the development of a commercially-led element that will attach as a new module to ISS, that can be used for research and government as a customer, but not the customer. But that’s only one-half of the equation. An economy is built of the supply side and, and the demand side. And right now, the U.S. government is virtually the only user of significance of the platform when we pay virtually all of the costs. And that’s simply not — not tenable going forward. We have to help enable other users of the LEO platform to see that they can actually do it and the national lab folks are going to talk about that, because they’re bringing in not only non-NASA players, but non-government players and that’s critical. About two or three years ago, we kind of stopped to assess what we’d been doing over the last decade or more, and what we were seeing was there weren’t a lot of return customers. And I use that term loosely. There were a lot of companies, commercial companies that were doing research, but it wasn’t a key element of their commercial research plan. And so, we said, what — why is that? And it’s because it — first of all they don’t understand microgravity. Secondly, it’s expensive to adapt your terrestrial research to operate in a microgravity environment. So, we started a very focused project to enable scalable, sustainable demand, non-NASA demand for a next-generation platform, using the space station while we have it. And so, space station program started investing in a portfolio of in-space manufacturing projects. Anything from retinal implants to bio-printing, to optical fibers, exotic fibers, silicon carbide. Things like that if successful, if you can prove that they’re orders of magnitude better than what you can do in 1 g, you can afford the cost of using space and all of the things that drive the cost for doing that. So, that portfolio is migrating to a new LEO commercialization office that the agency has stood up. The agency actually adopted a very broad LEO commercialization strategy over a year ago. And so, the bits and pieces that the ISS program had been working on for years have now coalesced into a cohesive strategy. And that’s pretty cool.

Gary Jordan: And I think what’s also cool, Mike is that it’s really — we’re talking about some of these recent efforts. There’s even a deeper history here. In fact, the International Space Station and NASA really, have always had relationships with commercial companies. John Mulholland, I’m going to pass it over to you. Boeing, in particular, has had an extensive history working with NASA. Notably, the company’s work on the shuttle and the International Space Station. Can you describe the relationship between NASA and Boeing, specifically for the International Space Station?

John Mulholland: Yeah, I mean I really think from a human spaceflight perspective, we’ve grown up with NASA. We’ve been NASA’s partner on every U.S. human spaceflight mission dating all the way back to Mercury. On ISS in particular, we’ve been NASA’s primary partner since 1986 when the ISS was still known as Freedom. Working with NASA we designed and built most of the U.S. segments. We integrated the international partners; we’ve been NASA’s primary partner throughout. Today, the focus is on sustainment operations. Make sure operations are — safely performed. And then, really importantly, looking you know, now and into the future, capability restoration and enhancement that’s really going to set the stage to do research on ISS over the next decade or more. And then payload integration. And payload integration is just hugely important because that returns the investment on the ISS. And as you mentioned, there’s been over 3,000 experiments done to date. Fantastic laboratory, and we’re just proud to have been NASA’s partner throughout.

Gary Jordan: And — that partnership really has been — is a continuing thing, right? What have you seen, John, in terms of the value, just working on the International Space Station program with NASA from Boeing for so long, what is the value that you have really seen with the International Space Station?

John Mulholland: Yeah, I think, you know, there’s — lots of streams of value. You know, one is the international collaboration and everything there. But really, what I think the legacy of the ISS is going to be is the research and discovery that’s — that we’ve had to date, and that we promise to show in the future. And just a couple of examples of research that’s almost getting ready to be fielded in a cure for Duchenne’s muscular dystrophy, that was fundamentally developed because of research on the ISS. And just, you know, in the last month or so, scientists completed research on a potential cure for leukemia. So, you know, between those, manufacturing in space, there’s just so much promise. Everything that we have done as a species, all the discoveries we’ve made, have been made under the influence of gravity. This is the first time that a national laboratory has been dedicated to research without the effects of gravity. And we’re seeing astounding results.

Gary Jordan: So, let’s explore that a little bit. The idea of the space station as a U.S. National Lab. Christine Kretz, at the top of this panel I mentioned more than 3,000 experiments have been conducted on the station. Thousands of researchers, more than a hundred different countries. Many of these experiments were conducted and performed were through the function of the International Space Station as a U.S. National Lab. Can you explain what that means and why it’s important?

Christine Kretz: Sure, that’s great, Gary, and thanks for the question. As you know, Congress opened up the National Lab as a way for researchers around the world, but U.S. researchers especially, to have access for non-NASA research. And Mike pointed out some of the things that NASA has helped foster. But opening it up to a broader group of researchers on Earth to think about how they may take that terrific asset that we have in space, and leverage it for their research was important. That spans academics, universities, startup companies. Mike mentioned the optical implant that is coming out of LambdaVision, from a startup organization, as well as working with industry partners, Merck, Pfizer, Sanofi recently. And then others like Adidas. So, having companies have access to the space station required something that was a kind of a non, non-NASA opportunity. That gives us 50% of the upmass and downmass plus 50% of the astronaut time. And with more astronauts onboard the station right now, that’s more astronaut time that we’re happy to have access to. It’s a lot of partnerships. And so, the partnerships that John mentioned are important. Partnership with NASA to foster that with us and help us collaborate together; partnerships with companies like Boeing that have sponsored the technology and space prize that created the opportunity for LambdaVision to put their application into space, partnerships with NSF (National Science Foundation) and NIH (National Institutes of Health), who also foster research like tissue chips in space that we work with; and then the commercial service providers, and Rich and Jeff are here today to talk about their efforts, they provide access directly through their operations to go to the space station, including STEM, other kinds of really interesting regenerative medicine research that’s going on. And a partner can go directly to their organizations and those commercial service providers access the space station through our allocation. It’s important just for the same things that Mike and John mentioned previously, which is really innovative efforts that would not be possible without the access granted by Congress in partnership with NASA to access that. So, some of the things mentioned here were muscular dystrophy, leukemia research, the regenerative medicine work that’s going on that may someday cause, allow us to have implantable organs. I mean it’s — it sounds far-fetched, but the direction to use this is really an amazing innovative platform. And because of the access that these researchers have, I guess it’s, it’s corny to say the sky is the limit but in fact, it’s amazing to see what people come up with and we’re really excited to continue to work with NASA and our partners here to allow that access.

Gary Jordan: Christine you’ve given so many fantastic examples of some of the research on station. And you mentioned opening it up as a U.S. lab in 2005 or at least the — push from Congress to do so. Have you seen an increase in participation in demand from when you first started opening it up as U.S. lab, trying to get the word out that there is this orbiting laboratory that companies have access to, have you seen an increase to where we are now in 2020?

Christine Kretz: Absolutely. The initial experiments were fewer and further between because researchers just weren’t aware of the access. And they — we had not yet developed the platforms that Jeff and Rich and other of our commercial service providers have created. So over time the word has gotten out, research has become more and more complex because of the kind of learnings that they have had. And again, that — the commercial service providers and implementation partners have built platforms right on the station–and I’m sure that they’ll talk about those more–that allow people to derisk their research allowing for more and more creativity and more success. In addition, as we learn more, those opportunities become more complex. And so, they take more astronaut time. They take more capabilities from our partners. And they’ve all risen to that and made those opportunities available. So, I started here only two years ago, and the types of things that I’ve seen, from the Tissue Chips in Space, which are going to be a game changer, to things that Rich can talk about, the BFF (BioFabrication Facility) and Jeff will talk about his platforms, it’s just amazing even in two years the changes we’ve seen, and what’s ahead for us. It’s really exciting.

Gary Jordan: I think that’s the perfect segue to you, Jeff. We mentioned long-standing relationships with John Mulholland not too long ago with Boeing. Nanoracks has also been one of those long-standing relationships with NASA, with the U.S. National Lab. Can you talk about some of these great things that Christine was alluding to that you’ve been performing as a commercial company operating on the International Space Station?

Jeffrey Manber: Yeah, thanks, it’s great to be here with my friends. You know when you look back on the International Space Station, it’s not just the hardware, though I’ll talk about that in a moment, it’s also a new system. It’s new partnerships between the private sector and the government. And so, probably one of the most important legacies at 20 years of the International Space Station is the public/private partnerships and the maturing of that. There’s no better examples, and let’s say the SpaceX and Northrop contracts and Boeing contracts for cargo and crew with, you know, with companies like Nanoracks, we’ve invested, you know, considerable money into our hardware, our platforms. We’re ready to go as we record this on SpaceX-21—Benji, make sure that thing gets up there, we got our Bishop Airlock on there. And that’s a permanent addition to the space station that’s privately funded. And we worked in partnership with Boeing on that. And so, the space station for me, is a lot of things. It’s first off, it’s stability. Bipartisan support. We don’t have bipartisan support for much these days. And we have it for the International Space Station. And that bipartisan support has given us the time to make these sort of investments, to work out the ecosystem that’s developing in low-Earth orbit. And you know at Nanoracks we have customers from over 30 countries. As I said, we’re investing in different platforms. We work everything from biopharma to satellite deployments. We’ve deployed over 280 satellites from the space station. We’ve coordinated over 1,000 projects. A lot of folks in my office call them payloads, but people outside of people like us don’t know what payloads are–they’re projects. And every one of those has a dream, and an aspiration and objective. And now, Nanoracks is recently announced that we’re going to be in the research business. We’re going to be I think one of the first companies in the industry to be supporting our own researchers, driving our own research in agtech (agriculture technology) and biopharma, and we use Rich’s hardware and our hardware and everyone else’s hardware. And so, you see that ecosystem developing. So, I guess for me at Nanoracks, we’re now 11 years into this journey, and it’s been wonderful to see the public/private partnership, partnerships mature with NASA and other government agencies, to see the customer base mature, they get more sophisticated. Now, we’re launching multiple times a year, and it’s really an exquisite sort of like Swiss clock. And it works, it’s wonderful, and it’s a delight to be part of.

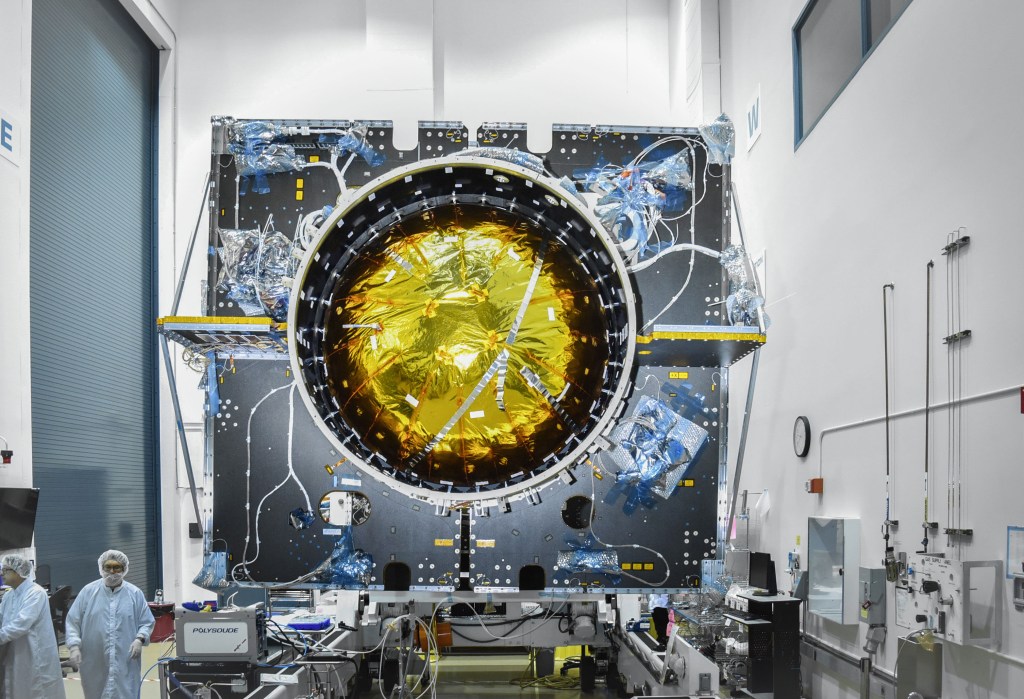

Gary Jordan: Now, the Bishop Airlock was one of those things that was mentioned, Christine alluded to it, Jeff, you mentioned it a few times. I think it’s a good model for — understanding what a commercial facility operating in low-Earth orbit is. Can you talk about that specific module, the Nanoracks Bishop Airlock?

Jeffrey Manber: Sure. We recognized early on that the JAXA airlock is wonderful. But we thought that there could be more business, more opportunity, grow utilization if there was a bigger airlock. And we went to NASA and as usual, unfortunately for Nanoracks, we didn’t ask for funding. We said, hey, if we put up this airlock–I’ll catch on Mike, at some point, I’ll think about asking for funding–but anyway, we said, hey, we’re willing to invest in having a larger, five times larger, airlock than anything that exists on the station. And so, we went ahead: we got partners with Boeing, we got partners with Thales Alenia and others. And we pretty well self-funded this airlock. We now have enjoyed contracts with European Space Agency, NASA, with some commercial companies, domestic and international. We’re scheduled, as we record this, to go up on the next cargo ship from SpaceX. And so there you have a wonderful example of a public/private partnership where the private sector comes up with a concept, comes up with the funding, is based on the investment the taxpayer has made, you know, over the last 20 years and beyond in the International Space Station. And frankly, now, NASA is coming in as a customer, but pretty much a commercial customer because they didn’t — fund us prior, they waited to see that we were moving along. And so, it’s still a fragile market, but couldn’t be more excited by the Bishop Airlock. It’s going to be a permanent addition to the station. And a great symbol for the growing maturity of the ecosystem.

Gary Jordan: Now Rich, Techshot is another commercial company operating on the space station. Now, through some of your work at Techshot can you describe some of the things you’ve been a part of, and the value that you’ve seen in low-Earth orbit?

Rich Boling: Sure, so we were founded in ’88, so, some of our first payloads were onboard space shuttle missions. And at that time, we — I think we outright owned one payload, but most of what we were doing was building them and turning them over to the agency. In the station era that sort of flipped and now we’ve developed nearly a dozen payloads of so many different varieties. Payloads, projects, perhaps, maybe we should call them. Many are onboard the station now and others are in the pipeline ready for applied certification. Those things are tools that enable research with fish, plants, cells, whole animals. We have an x-ray machine for mice onboard the station now, and we’ve done 156 x-rays of mice so far. One of the more interesting ones of those was for the research team of Se-Jin Lee and Emily Germain-Lee–the Mighty Mice that I think a lot of people have heard about. We were proud to play a role in that mighty mouse, Mighty Mice research that showed that some of the treatments they gave those mice, the muscle wasting was not only reduced but in some cases some of the animals came back stronger from space than when they went up. And obviously, that has terrific implications for long-term spaceflight crews. But also, folks here on Earth who have muscle wasting disease could be a real game changer and perhaps one of the most important things that we’ve been a part of at a station. But others are also very exciting. We’re getting ready to launch some squid on SpaceX-21. And so, there’s quite a wide variety of equipment that, most of which we provide as sort of a picks and shovels model where it’s not our research, it’s the research of our customers, and we provide the whole ecosystem of what they need to get some amazing results in space. I mean microgravity has a way of sort of lifting the mask off of biological processes, and allowing researchers to understand more about what’s going on inside of a biological system. Sometimes that means that they need to go back in space and continue either research or some manipulation on orbit. But also, it might mean that they’ve learned something in microgravity that they can apply and replicate on Earth, which also I think is helpful to the industry. You know, but, our payloads, our projects, are divided into a couple categories. One is what we do provide for those customers of ours. But then the projects that we take on for ourselves with our internal science team. And those are related to things like what Christine and Mike alluded to with our bioprinter. So, the Techshot 3D BioFabrication Facility, which we developed in partnership with a company called nScrypt in Orlando, which we think makes the world’s finest terrestrial 3D printers, and the bioprinter is something that is a project of Techshot’s, the research is ours, we’re doing the research internally now and occasionally bringing in outside investigators when it makes sense. Also, working on a cell factory, Techshot’s in-space manufacturing capability, to be able to make all sorts of stem cells in space for either cell therapies on Earth or for research by our own customers, we can provide a source of cell manufacturing on orbit. And then lastly, we’re working on a 3D metal printer for the station as well. That hopefully will be able to prove its use to make aerospace-grade things like titanium, which also will help exploration crews going to deep space, and even on the surface of Mars. But these technical accomplishments I think are definitely important. But Jeff talked about just the infrastructure, whether it’s the technical infrastructure or just the policy infrastructure that’s been established. And I agree that I think that’s going to be, this NASA democratization of space where I think it has intentionally fostered entrepreneurial participation, I think that’s going to be regarded as one of the station’s most important achievements. And to me, this kind of leadership in technology and enterprise in space seems to be a very American thing to do. We’re excited to be a part of it.

Gary Jordan: Rich, you’ve explained so many fascinating types of research. And I think people listening may be surprised to hear just how many different areas there are–material science, biological science–and some of them may want to get involved as well. Can you kind of draw some lines and — to connect with some of our panelists today? We have representatives from U.S. National Lab, we have you from Techshot, we have NASA. Can you talk about the relationships with Tech – with Techshot and with all of these different elements that bring this together for those that may also want to get involved?

Rich Boling: All right, so, first of all, part of that intentionality that I mentioned, which I think is not to be quickly dismissed–I mean Mike’s office, Mike’s been involved in the commercialization of station for a long time, and he talked about how he’s seen an evolution of what works and what policies that NASA can put in place to foster this, so, we worked with Mike’s office, had a Space Act Agreement established years ago, as I know Jeff has as well–and so, without Mike’s office we couldn’t do this. We launch on essentially every SpaceX cargo Dragon. And without that resupply capability, especially that returning capability, we couldn’t do what we want to do. Once we get into more of a production mode with human tissue, which again, I don’t want to give anyone the idea that this is happening next year but it looks good, it looks promising and we need that return capability to bring those things we manufacture for patients back to Earth. And Christine mentioned the allocation and the fact that we can partner with the ISS U.S. National Laboratory to, frankly, not only to manifesting, but also, we rely on them and partner with them and just helping potential customers understand the value of microgravity. They’ve got some tremendous resources on staff that do a far better job than I do about explaining the value and the benefits of microgravity to material science folks, to people in industry and pharmaceutical companies. And for so many reasons we rely on folks like Christine at the national lab. And then even competitors. Jeff and I, we don’t compete in every aspect–certainly, we don’t launch CubeSats or things like that–but I do still consider his success my success and success of the industry. This is, frankly, a small industry compared to so many others. And I do cheer on the success of Nanoracks, Space Tango, BioServe and others because we want to grow this pie. We want to — we want to rally and build demand for ourselves and right now that also means helping others build demand for their products and services. So, it’s definitely an interdependent ecosystem right now.

Gary Jordan: Thank you Rich, you can really get a sense of just all the commercial work happening in low-Earth orbit. I think another really important piece of this puzzle is the transportation to and from low-Earth orbit. We’re talking about what’s happening on low-Earth orbit, but that transportation is another critical piece. Over the — over the past many years cargo has been delivered to station by way of commercial spacecraft. Now we’re bringing on the next generation of human-rated spacecraft. So, I want to shift gears from some of the work on International Space Station to these transportation capabilities. Benji Reed, I want to pass it first to you. We’re not too far removed from a huge milestone: Crew-1, the first crew rotation flight on a commercial spacecraft just arrived at the International Space Station with four astronauts, who will now call the station their home for the next six months. First of all, congratulations, what an incredible achievement for SpaceX.

Benji Reed: Well, thank you very much. Thank you for having me on the panel today and — you know, always massive congratulations to the — space station itself and the program and all the partners involved in making it happen. Our industry partners and NASA partners, and international partnership. But yeah, I know it’s an amazing accomplishment. It represents the work of thousands of people, SpaceX and NASA joint teams, dedication and sacrifice by them and their families to pull it off. And of course, you know the — most exciting part is for those four crew members, for Victor (Glover), Mike (Hopkins), Shannon (Walker) and Soichi (Noguchi), and their dedication to going up and living and working and doing all of the science and commercialization efforts that we have to do and always, thank you to them and their families for trusting us in that transportation and bringing them up there and bringing them home safely. So yeah, you talk a lot about transportation, and I think it kind of — looking at the big picture, and Rich used a really good word, intentionality. SpaceX was founded — and continues to focus as our number one mission is fundamentally to make life multi-planetary. And those aren’t just words. That’s the real deal. That’s what we do. And so, when you look at that picture you say, OK, well what does that mean? Well first of all, the nearest planet is Mars. What do we have to do to make that happen? Well we’ve got to put thousands of people on Mars. We have to put thousands of tons of cargo on Mars. And probably more, right? Thousands, tens of thousands, hundreds of thousands. Ultimately, you know, a self-sustaining civilization on another planet is going to look like at least a million people. And that sounds mind blowing probably to most people right now. But that’s the reality of what it’s going to take and that’s the intention — the intentionality and that’s the mission of SpaceX, and I think a lot of us. I mean we all really want to see this awesome future where, you know, humans are a space-faring species, where we’re carrying you know, our adventure, our learning and our exploration to the stars. And again, this is exactly what we’re seeing in low-Earth orbit, and what we’re seeing on the space station that has benefits back home, you know back on the Earth, and to a lot of terrestrial applications. But how to do that, so you spread kind of a practical set of steps as you think through the problem, right? Eventually I need to put thousands of people and thousands of tons of cargo all the way on another planet. And what are the barriers to that? So, you look at the barriers and you say, well, number one, I need the technology to do it. And number two, I need to drop the price. The cost is the problem, right? The cost of space is really the fundamental limiting factor in the equation, in this whole experiment of space exploration. The limiting factor is how much does it — how much does it cost per pound to get, to get things up there. Because that cost not only is a cost directly on your project, right, but it’s also, it increases the cost of the project itself. If you’re going to spend, you know, thousands or millions of dollars for a launch, or to be a piece of a launch, and now you’ve got to worry, well I’m going to only send one of these things up there, and it’s got to work, it’s got to be perfect. And so, you spend a lot of money and a lot of time making that one thing work really, really, really well and have high, high reliability. Whereas when you look at like, well how do industries take off, how do economies take off terrestrially and historically? Well, a lot of times it isn’t because you built one car, right; they didn’t come off the line and say, I’m going to build one car and it’s going to be the perfect car and it’s going to work forever. Well they built a lot of cars to start with and there was a lot of people actually working in it. Any invention or, you know, that you look around, there’s actually a lot of people working in that. And a lot of different, and a lot of failures have happened. So how do you, you want to be able to, again, you have to drive that overall price down, so there can be many, right? There has to be — usually we keep using these terms like ecosystem and others that are very biologically-based terms, but there’s a good reason for that, right. That’s the way life works. Biology is a, it’s, you know, there’s a ton of different options. There’s a huge diversity of opportunity. And that’s how you — that’s how you ultimately evolve and grow. And that’s what we have to do here too. So, what do we do at SpaceX? So, then you go to the next step of the problem. OK, well how do you drive down cost? Well, the cost of transportation ultimately is the lack of reusability. Right? If you have to build…we always say it, but it’s always worth repeating: you get on that big jet airplane and if you had to — you know, fly across the country from New York to Los Angeles and then you’re done with that flight and you push it into the ocean, that’s going to be a pretty expensive set of tickets. And so, we started working, you know, from the very beginning on how do we refly rockets? How do we reuse those rockets? And ultimately, you know, all of the pieces of the spacecraft, everything that we can do. Huge partnership with NASA on the COTS (Commercial Orbital Transportation Services) program, the original cargo transportation services program and the development there. We developed Dragon on that program. And we developed Falcon 9 on that program. Both of those, the Falcon 9 now, of course, is being used across many different — for many different customers. And for many different programs, government and private and we see how that works together. We’ve flown Dragon now to the space station and home 20 times in that time. That Falcon 9 that was developed has flown over 100 times; over 60 times it’s reflown, which is great, and really kind of amazing when you think about it, just over the last few years. But we are starting to see that, right, we’re starting to drive down those prices. Ultimately, the cost of space and space transportation needs to be driven down by an order of magnitude. You know, by, divide by ten and then divide by ten again, probably two orders of magnitude, to actually get to these goals. And we’re going to get there; we’re going to do that. And then, so, serving the space station you talk about, and one of the things that was mentioned was the bringing of things home, which is very, very important, right? The goals for going multiplanetary [is not to] send people away and never come back, right? We actually, we want there to be this like interchange, this interchange of transportation. And so, this is the space station and the work we’ve been able to do with them and NASA and all of these great partners that we’ve been hearing from today and others, is about that bringing things up and bringing them home and being able to learn. So, from the beginning, Dragon was designed to fly lots of science, lots of payloads to the space station and bring it home safely. And there’s other partners out there who are also working on those technologies, too. And also, from the beginning, Dragon was designed to be able to fly people. And fly and maintain life and you know, biological payloads, if you will, for like the, we talked about the mice earlier, and it’s cool to hear there’s going to be squid on there, and, you know, on CRS-21, the cargo vehicle 21. You know, and there’s a lot — we’ve been actually flying a lot of biological cargo for a long time and maintaining environments even for non-bio cargo that needed to, on Dragon for many flights, for many years. And then, yeah, now culminating with our Crew Dragon, which is our Dragon 2 line, and then coming up this CRS-21, this cargo 21 flight, will also be on the — it will be the first flight of Dragon 2, that line, the first cargo variant of that. Excited to bring up the Nanoracks docking area and that’s going to be fantastic. Like we’re super excited about that. And I said docking area–airlock, say that correctly. But, you know, ultimately, we just see this partnership continuing, you know. We’re looking forward to — I love the fact that the Crew-1 crew that went up just now, they’re spending their next few weeks not only kind of getting oriented, but spending a lot of time catching up a lot of the work that’s, that’s on station that needs to get done, doing a lot of the science work. And then getting ready for 21 to show up, which is going to just have a load of science. So, kind of that’s the big picture and that’s where we’re seeing things heading.

Gary Jordan: Benji you describe so well the ambitions and the model that you’re using to create this commercial economy. That’s really what we’re talking about today, an economy. And I know NASA’s goal is to be one of many customers, right, in a self-sustaining, robust economy where commercial partners are in low-Earth orbit. For SpaceX can you talk about some of the ways that you are participating in, existing in this market, right. With Crew-1, NASA was the customer, SpaceX provided transportation so that NASA can have astronauts onboard the station to conduct science, but we want to be one of many customers, right. So, talk about how the Crew Dragon will participate in some of the ambitions NASA has put up like private astronauts in the low-Earth orbit economy.

Benji Reed: Sure, absolutely. Well very similar to what happened with Falcon, right. Again, we developed Falcon 9 as part of that COTS effort and, and for to put Dragon, to take Dragon to space station. And now we again, and a very good example, NASA is one of many customers on the Falcon 9 rocket. And we’re going to start seeing the same thing on Dragon as well. Dragon primarily has been [inaudible] space station and home. It’s also designed to do free flight. And so, basically, doing orbits in low-Earth orbit, in LEO, and you know, can stay up for a number of days or depending on the different activities that we can do. We can do science in those — in low-Earth orbit. We can carry payloads in the trunk, in the back of Dragon for non-pressurized cargo. We can carry lots and lots of cargo inside and we can carry people as you were — as you were alluding to. And so, there are many different options there, right. And now, we’re also — we’re already seeing another ecosystem and economy, right, whether we’re bringing people up ourselves, you know, customers who are coming directly to us, to be able to fly on Dragon and fly astronauts on Dragon, private astronauts, private spaceflight participants. We can fly them in Dragon directly ourselves as direct customers to us. We can also provide those transportation services to a variety of other companies that are, you know, essentially, brokers who are putting together a whole plan. There are a number of people out there looking at different opportunities for private space stations or private elements of space stations, you know, exactly what Nanoracks is doing, you know, and starting to look, how can we add to the space station as it is, and eventually, how can we create, you know, commercial space stations? And those, all those folks all need transportation services as well. And transportation for cargo, for science and, of course, for people and for astronauts. There are other nations that very much want to be involved in space. And they want to become spacefaring nations with their own astronauts. And that’s another opportunity there, where they can actually, now, directly buy a seat and buy an opportunity to fly, and fly in Dragon. So, lots of things and I assure you there’s a lot going on and we’re going to be excited to see a lot of it. We’re already starting to hear some of the announcements and talk about things like that. And then as we move forward, you know, we’ve got to keep going. That ultimate goal is out there, which is a shared goal with NASA as we look at this commercialization beyond LEO. And we look towards getting to the Moon and getting to Mars and so, we’re building the Starship, which will do the same kind of things and be fully reusable. So, very exciting future ahead. And lots of partners and lots of customers beyond NASA.

Gary Jordan: Ven, Benji was talking a lot about the Crew-1 and some of the ambitions there. We’re talking about the Crew Dragon. This was part of NASA’s Commercial Crew Program; Crew Dragon is one of those vehicles, Boeing Starliner is the other. Can you talk about some of NASA’s goals by having this program and bringing up these capabilities for transportation?

Ven Feng: Yeah, absolutely. You know as a Commercial Crew Program and also as CRS (Commercial Resupply Services) program, you know, with, really transportation organization is what their overarching goal of helping to certify and fly rockets and spacecraft as safely and as quickly as industry can do it. So, with these investments, you know, not only do we, are we celebrating the 20th anniversary of the International Space Station, which is a huge, huge thing–now in Expedition 64 of the ISS–but we’re also celebrating the ten-year anniversary coming up in just about two weeks here for the first COTS demo flight number one, which was just under ten years ago. And since that time, commercial industry partnered with government and completed 34 cargo resupply missions to the space station, as well as just this year, just in the last six months, we’ve now, SpaceX has accomplished two crewed missions to the ISS, both with Demo-2 and now with Crew-1. So, so yeah, it’s been a tremendous accomplishment for these commercial/government partnerships. So, yeah, so we’re very much looking forward to SpaceX becoming a very regular occupant of one of the two docking adapters up on space station. We’re looking forward to Boeing coming up in a matter of months. They should be coming back up to space station, we’re working very hard to ensure that everything is ready and they’re very closely behind. So, it’s really a very exciting time. So, when you look back it just, again, the big scheme of things for LEO commercialization, ten years ago the station was established—no, I’m sorry, twenty years ago, the station was established; ten years ago we started these commercial partnerships and now, nearly 40 flights later, we are continuing and going on to the next thing also with not only with SpaceX and Cygnus, on the cargo side, but also Sierra Nevada coming up here in the next year or two.

Gary Jordan: Quite the landscape. Phil, I want to pass to you. Mike Read in the very beginning of this panel talked about some of the recent accomplishments and opening up the station for business and some of the recent efforts for commercializing LEO. Can you talk through some of NASA’s recent accomplishments, accomplishments so far to support some of these commercialization efforts?

Phil McAlister: Yeah sure. So, when I saw that I was going to be the last speaker, I’m like, oh, that’s great, I can sort of adjust my comments accordingly. The downside is that there’s almost nothing more to say, right? Everything, everybody has covered something: I’m like, OK, Rich said that, Mike said that. I’m not sure what I can add to that very good tapestry that I think everybody has laid out for ISS. Obviously, we’ve had some very recent successes with having the ISS as this critical test bed to experiment. And I use that word literally and figuratively, right: actually, doing research experiments, but also, experimenting on what works and what may not work, in terms of economic activity and commercial activity on ISS and in low-Earth orbit. So, ISS has been a key platform, we’re really just seeing some traction now. I think it has to do with the fact that we actually have human commercial space transportation now, available through the SpaceX Crew Dragon and very shortly thereafter, Starliner. So, we’re seeing a lot of traction on private astronaut missions that go to the ISS. And not only that, just completely private missions that don’t even go to the ISS. There was a recent announcement by SpaceX and Space Adventures just to go in space, and not to dock with ISS. And NASA will have nothing to do with that project. And that’s exactly what we want to see. And we’ve also seen some successes that, on the demand side, on what we’re actually doing in the ISS. We’re seeing some more commercial development projects that are coming up to the ISS. So, so, when I think of the overall sort of commercial LEO development activity that we’re doing, the ISS is obviously been a critical test bed for that. So, I think everybody at NASA when we think of the ISS, we want to give it the Vulcan salute, and say “live long and prosper,” but this 20th anniversary is an awesome celebration, but it’s also a reminder that the ISS is not going to be around forever. It could experience an unrecoverable anomaly at any time. And so, as amazing as it is, it’s also a reminder that that is our, that is our single toehold to continuous human presence in low-Earth orbit. So, it’s my job to ensure that we do not have a gap for whenever the ISS retires, whenever that is. And so, when I look back historically, Benji and Ven also mentioned, you know, we started with cargo and then we have crew — Commercial Crew — and I think our long-term vision is then to have commercial destinations. And once we have all three of those in low-Earth orbit, primarily driven by private sector interests, you have this self-reinforcing ecosystem. I know we’ve used that word a lot, but I really think it applies here. Self-sustaining, and self-reinforcing and that’s what — that’s what the commercial LEO development program is all about. We are looking at, eventually, having multiple space destinations. Again, the sort of tenuous nature of just having one platform up there, as amazing as it is, reinforces that I think we need multiple destinations. Just like we have multiple commercial cargo capabilities and soon commercial crew capabilities, having redundancy and having multiple capabilities is going to be key. And I think when we look in destinations, when we, we’ve talked about all the different things that we can do in low-Earth orbit, not every destination is going to be good for every kind of application. So, we could see sort of tailoring of this destination for this particular market, this destination for another different kind of market. But you look overall, and you have this sort of rich tapestry, capability, redundancy, that I think we all want to take advantage of. Not just NASA, as Mike said, we are going to have continuous requirements in low-Earth orbit. We’re going to be a good anchor customer for these capabilities. But as we’ve said many times, it’s not just a cliché, we want to be one of many customers. So, we’re hopefully going to enable that capability to be sold to other customers. And I do agree with Benji completely, the key is cost. Right? As amazing as the ISS is, we’ve always been conscious of cost with the ISS, but it wasn’t really developed with that as the primary driver. It had other things that we were trying to accomplish. When you partner with the private sector, they have a laser focus on cost and schedule. And then you bring NASA’s experience with human spaceflight, our 50 years of human spaceflight, and you put those together it’s a very, very powerful combination. And we saw it with cargo, we saw it with crew, and I want to bring those lessons learned with commercial space destinations and make sure that they are online whenever the ISS retires. And I think once that happens, NASA can then set its sights deeper and really allow the economic activity in low-Earth orbit to really take off.

Gary Jordan: Phil, I think you said it so nicely. And I’m sorry for making you the last speaker but you said it that, you know, we’ve covered so much. Man, we talked about the International Space Station and some of the great work happening onboard with a lot of our commercial partners. We talked about the transportation capabilities. And Phil, you ended so nicely with under, giving us an understanding of what this framework, you know, what is a robust ecosystem, understanding sort of what that looks like in low-Earth orbit. So, I’d just like to end there and thank each and every one of you for taking part in today’s discussion. What a truly enlightening and fascinating discussion we had today. It’s been an honor to host such an esteemed panel and chat with you all today. So, for those listening and tuning in, thank you so much. If you want to know more about NASA’s low-Earth orbit commercialization efforts visit NASA.gov/LEO-economy. As always you can follow us on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram. And other social platforms and ask us a question using the hashtag #AskNASA. Thanks so much for tuning in.

[ Music]

Host: When I got to NASA in the mid-1990’s and the modules of the International Space Station were still being built, and there were days when you’d be forgiven for wondering when this whole thing was even going to get off the ground, the program goal of promoting commercialization of space and space research didn’t seem like such a big deal. Now, it’s hard to imagine what the station would be like today if we didn’t have the vital contributions from and participation by private companies, including those represented in today’s discussion and many, many more. As we move ahead in the Artemis program, look to see how the lessons of the value of commercial partnerships is being applied to the next goals of space exploration. There’s more to come on this celebration of the space station’s 20th anniversary. The next discussion focuses on the critical importance of the partnership built by the United States and NASA and nations and space agencies from all around the world. That’s coming up in a couple of weeks. I’ll also remind you that you can go online to keep up with all things NASA at NASA.gov and you can find the full catalog of all of our episodes by going to NASA.gov/podcasts and scrolling to our name. You’ll also find all the other cool NASA podcasts right there at the same spot where you can find us: NASA.gov/podcasts. The panel discussion in this episode was recorded on November 18, 2020. Thanks to Alex Perryman, Gary Jordan, Norah Moran, Belinda Pulido and Jennifer Hernandez in putting together the podcast and to the NASA JSC External Relations Office for putting together this episode of the anniversary panel discussions. We’ll be back next week.