From Earth orbit to the Moon and Mars, explore the world of human spaceflight with NASA each week on the official podcast of the Johnson Space Center in Houston, Texas. Listen to in-depth conversations with the astronauts, scientists and engineers who make it possible.

On episode 303, hear from the CHAPEA crew and the principal investigator as they give us an update on how life has been in the simulated Mars habitat. This is the first audio log of a monthly series. This episode was recorded on August 2, 2023. Recordings were sent from the CHAPEA crew throughout July 2023.

Transcript

Gary Jordan (Host): Houston, we have a podcast! Welcome to the official podcast of the NASA Johnson Space Center, Episode 303, “Mars Audio Log: #1.” I’m Gary Jordan. I’ll be your host today. On this podcast, we bring in the experts, scientists, engineers, and astronauts, all to let you know what’s going on in the world of human spaceflight and more. Four humans are currently on Mars. Well, sort of. Four individuals are in the beginning of a year-long analog mission in a habitat right here on Earth that is simulating very closely what it would be like to live on Mars. The analog mission is called CHAPEA or Crew Health and Performance Exploration Analog; and more so than a technology demonstration or a human Mars mission dress rehearsal, the primary purpose of this study is human research. A deep study into understanding what life would be like if you actually had to be there for a full year. We got a chance to chat with the crew before they began their journey on episode 295, and they shared their background and mindset of entering this habitat for a year. We are lucky enough to have regular access to the crew through their journey, and they promise to record audio logs about their experience month to month. On this episode, we hear from the CHAPEA crew for their first audio log. To add some context, we’re also bringing in Grace Douglas, CHAPEA principal investigator, to describe more of the science behind the mission. Very excited to hear from the crew inside CHAPEA for the first time. Let’s get into it.

[Music]

Host: First is CHAPEA Mission Commander, Kelly Haston.

Kelly Haston: Hello, my name is Kelly Haston. I’m the commander of Mission 1 of the CHAPEA project out of Johnson Space Center for NASA. Right now, we are in week four of the mission and things are running really well and the team is feeling great. I personally am also feeling great. We’ve really continued to be a strongly collaborative unit and we have moved through each week’s mission’s goals in a strong and efficient manner.

The funny thing about when we walked into the habitat for the first time at the start of the mission was that after the ingress ceremony on the evening of June 25, we were sort of finishing up months—almost a year—of anticipation for this mission and a very long month of training, and then a really long Sunday waiting for ingress to occur in the evening. So, we were so happy that as we came through the door and it closed behind us, we formed this spontaneous sort of group hug and let out a big cheer. And it made the crowd watching us, watching the ingress, laugh. So that was the first thing we did. We had sort of a big group hug, and then we heard everyone laughing at us. Then they also clapped and cheered for us as well. So it was a really cool start.

After we entered, we kind of all walked around the habitat looking for changes that had been made during the final preparations because we’d spent time in the habitat, you know, during training. Then we had a few days where we weren’t in it as they made final preparations. But this was the first time that we were in it alone with no other, none of the other people training us, so it really felt like it was our space for the first time and that was a really cool feeling. So we kind of walked around just checking everything out again, looking for things that they might have added. Then we also spent some time unpacking our gear and setting up our bedrooms. But before we went to bed that night, we had a celebratory hot chocolate as a group sitting around the table for the first time. And that really sort of cemented the start of the mission. We clinked our glasses, our mugs, and we were really excited to get started. Believe it or not, that first night of sleep was actually really solid. I had no problems or weirdness, and actually really felt comfortable on the bed and in in my room.

Kelly Haston: So, a lot of people ask about the food. The food is actually really good. We have a lot of variety, more than I expected, and we document everything that we eat and drink, even like a shake of salt or pepper. So our meals tend to have a lot of discussion about the merits of a given item, what values it might get you for calories or protein, and how things go together. As a matter of fact, there’s a document circulating amongst the crew that keeps track of the best combinations of meats and vegetables or other side dishes so that we can keep track of the items that we like best and how they actually sort of complement each other. So that’s actually been a very robust set of conversations that we have that we never seem to get bored of.

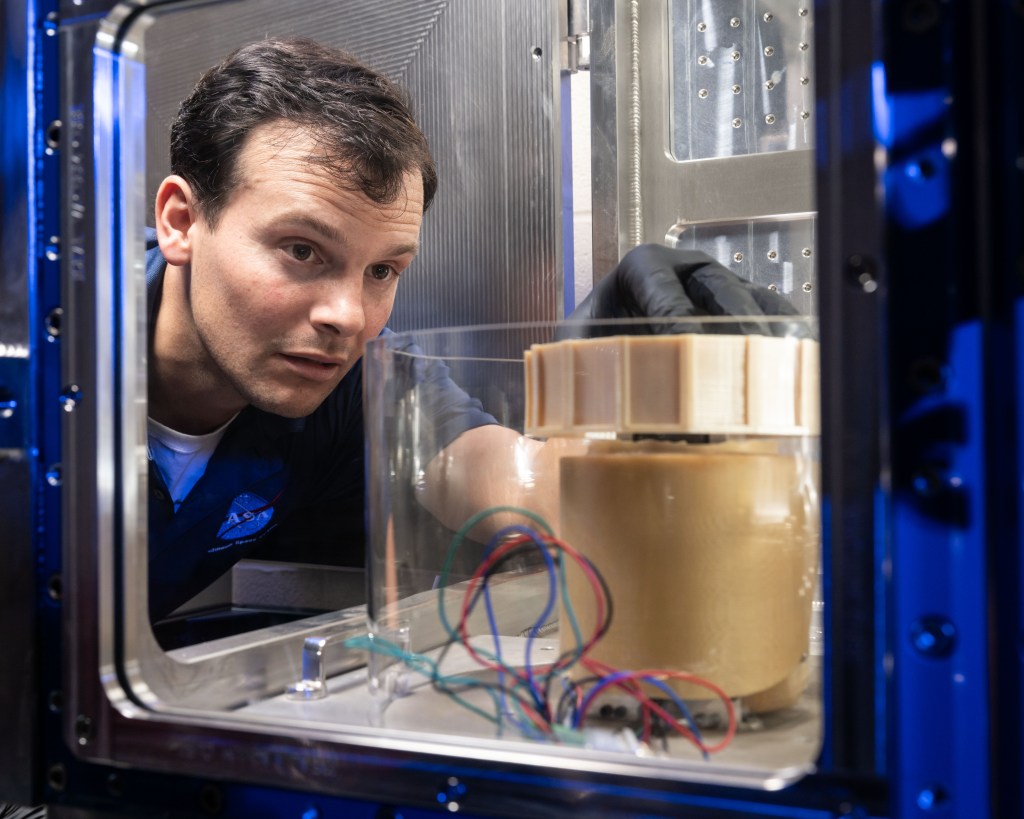

Daily, we have a lot of different tasks that we do as you might imagine in a Mars base that is, you know, one of the first of its kind on a new planet. We have a pretty high variety of tasks, and each week tends to have a particular flavor, so we’re usually focusing on something fairly strongly in a given week. Some weeks we’re focused on EVAs, or Extravehicular Activities, where we go outside the habitat and walk around on Mars and perform different tasks. These would be in line with what you would expect to keep a Martian base running, and sometimes utilize virtual reality and other times do not. The virtual reality is really fun and very beautiful, but each EVA has a particular sort of goal that we are trying to achieve in a certain amount of time. So we’re usually pretty serious out there, really trying to get our work done. But we have a lot of fun as well.

Kelly Haston:You know, the first few weeks have actually really been in line with what I expected, both from the information that we got during our evaluation and also during training. And also the team that got us ready for the mission during training did give us a preview of the first month’s schedule. So, we had some good information about what was going to happen to us the first month, which was really helpful because there were less surprises than maybe we’ll get in the future as we were settling in and sort of establishing a lot of our schedule and work norms. So that was actually a real positive for the team. We got to actually sort of know what was coming, we didn’t always know what it was going to look like, but it was really helpful

I guess the thing that surprises me the most is not actually the work or the workload or any of the things that we’re doing, because as I said, we kind of had a pretty good idea of those. The surprising thing for me is that I don’t actually miss outside yet. I mean, of course, I miss my family and my friends and my partner and that’s sort of normal. But you know, especially given that it’s summer and everyone is out doing cool things and you know, we’re getting that information from our friends, I don’t actually miss being outside; and going outside the habitat into the Mars space has actually been really satisfying. So maybe it’s fulfilling that need for me for exploration that I often do in my normal life. I think it also suggests that we’re really able to drop into the simulation that we’re part of, both personally for me and as a team. So that’s been actually a really, really awesome finding that we’re all actually feeling pretty content here so far, or at least I am for sure. I think the rest of the crew feels like that

So finally, what’s coming up in the next month? The upcoming month, we’ll have some things that are similar. We do some things that are repeated or sort of similar to what we’ve already done. So as an example, when we do the EVAs, we’ll often do something that is similar or has the same flavor. An example of that would be, you know, sometimes we go out onto Mars, and we might do something like set up or build some scientific equipment or other times we might be collecting samples. Even though there are different activities once we get out there, the process of entering and exiting the habitat and some of the procedures we have to go through, those are all similar. We all have sort of established a baseline behavior around them but then when we get out, we get to do something a little bit different each day or each time that we go out. We’re moving through a process of getting to know many of those things, but some of them will repeat, you know, regularly because we have to check certain equipment out there and so forth.

So we have some repeat things, but we also have some really exciting new missions in the coming month. Some of that will include using different types of virtual reality or remote control methods from inside the habitat to accomplish goals outside of the habitat. So we’re sort of building on the skills that we’ve been sort of gaining in this first month in the mission. That’s actually going to be a really exciting area to keep an eye on and see how we grow as a team and as individuals. But it’s really fun and cool tasks that we get to do. So I think everything is actually pretty happy and rosy here in Alpha Dune on Mars and we’re doing really great as a team and really grateful that people are following us and interested in our progress.

Host: Alright, that was Commander, Kelly Haston, kicking us off. Great to hear that the crew is off to a great start. Next is CHAPEA Mission Flight Engineer, Ross Brockwell.

Ross Brockwell:Hello, this is Ross Brockwell. I’m flight engineer for CHAPEA Mission 1, also known as the “FEN.” It’s July 17, 2023, and I’m answering some questions from Houston We Have a Podcast. So first question, “how are you feeling right now?” I’m feeling really good. It’s actually been a lot of fun. Everything’s really exciting. Coming in here was something [laughs]. It was a really interesting experience, the ingress ceremony. And, you know, the four of us and the crew have been looking forward to it for so long. That coming in was really special. We kind of shared a moment when we got in here and then kind of went around making ourselves at home. So that leads into the second question, which is “tell us about the moment you walked through the hatch and began your mission.”

That was very special. The ceremony was great. All the staff were really supportive. Everyone’s very smart, very interesting, very helpful, very committed to the project, so it was really great to actually kick it off. They’ve really tried hard to put a high level of realism into this, so it was exciting to kind of come through there and felt like we really were launching on a journey.

So what were the first things we did after entering? Well, we did share that little moment where we all kind of did a group hug and, you know, cheered a bit. It was nice to finally be here. Then we unpacked some of our stuff and settled in a little and we actually hadn’t eaten much that afternoon, so we went to the food stocks and started that process and selected a few things to eat. Had a little bit of a meal and just kind of took it easy. It was already a little bit late at that point, so it wasn’t too long before we went to bed.

And how was our first night’s sleep? Very peaceful, very restful. Really nice to be in here having the mission started. So, you know, we were tired anyway, but our minds were racing as you would imagine, but once we laid down and settled into the room and turned the lights off, for me personally, it didn’t take very long to fall asleep. Felt great to be here and be in the first night.

Ross Brockwell: So, how’s the food? The food’s quite good. Pretty good variety. Some things stand out. Luckily for the crew, the tastes vary enough to where, you know, a few people have a few different favorites, they don’t overlap too much. The system’s working really well so far. I mean, they call it pantry style. So all the food for the food timeframe is just kind of put in drawers and cabinets and you kind of go through and eat what you feel like. It works out pretty well. So we kind of alternate between just individual items prepared and eating out of the bag. Or you can make a plate, you know, a full-scale meal. So it’s great. They’re really enjoyable.

What tasks do they have us doing? So, it’s a lot of things that you could imagine would be necessary on a real mission. It’s internal maintenance things, maintenance on the habitat. There’s all the health and fitness stuff that we have to do. There’s training we have to do. There’s preparation for specific activities like the Extravehicular Activities so sometimes there are pre-brief sessions to prepare for those. So it’s pretty scheduled. They have a playbook as the program we use for organizing our days. So all those tasks are itemized and laid out and a plan for us that we go through. There’s a little bit of flexibility to it, but not too much. So those things fill up the day and there’s some time too for some personal stuff, for some training of your own choice or communication with family and friends and reading and study and we have access to movies and books and the library we brought in with us; so lots of things to do.

Ross Brockwell:Are the first few weeks in line with what we were expecting it to be like? What is in line and what’s more of a surprise? I would say yes, things are going pretty much as would be expected. I wouldn’t say anything’s really been a surprise. I mean, it is interesting how specific the timeline is laid out for us. I guess I thought it might take us a little bit longer to get into a rhythm, but the things are pretty intuitive. We have a pretty good dynamic between us, so it doesn’t take too much effort to communicate ideas and changes between the crew. I think we’ve picked it up pretty quickly. The first few weeks have flown by. We’ll see if there are more twists and turns in the schedule. I’m sure there’ll be unexpected things that crop up we’ll have to adjust to. But I think we’re think we’re ready

So as to what’s coming up in the next month, I’m sure there are some things that I can’t predict, but there will be another series of EVAs. Some of those are in the virtual reality world, which is really great. It’s pretty well done, really neat to be out there in a virtual Mars surface. It’s pretty high fidelity, it’s pretty immersive. Those are really interesting. So kind of getting to know the area around the habitat and where all the facilities are that we have to maintain, comms towers we have to align and solar panels we have to maintain. You know, geology we have to do, it’s all really interesting. There’ll be some more real-world EVAs where we go out into the sandbox and work on equipment and build things. Then there’s periodic fitness and health testing we have to do, some biological testing we have to do. There’s all that coming up. And then before long we will get into our crop cycle, our food growth, which we’re all really looking forward to. So far things are going pretty well, I think, and I hope it stays that way. Okay, well thanks a lot and I’m sure we’ll talk again soon.

Host: Again, that was Ross Brockwell, flight engineer. The last two crew members recorded their audio log together. But first, we’re going to speak with Grace Douglas, CHAPEA principal investigator, to add some context. Grace Douglas, thank you so much for coming back on Houston We Have a Podcast.

Grace Douglas:You’re welcome. I’m very happy to be here.

Host: In person, too. Last time we talked was during the pandemic and we got to do it as part of our Mars series. You talked about the Mars advanced food systems and we had to do it remotely, but now we get to do it face-to-face.

Grace Douglas:Yes. Very excited about this.

Host: Yeah. Since we last talked, actually, funny enough, when we talked, it was part of our larger Mars series. We were trying to capture a human mission from Earth to Mars and back. And you told us the story of the food system and what we’re thinking about for Mars. Funny enough, we were talking ahead of this recording and you were saying that even while we were having that conversation for the Mars series, you were planning CHAPEA. You were sort of in the middle of all of this because it took you quite a bit. I guess I didn’t realize just how long it took to get us to actually the moment of ingress. So you were behind the scenes just making this happen all along the way.

Grace Douglas: Yeah, so I started working towards this mission six years ago, and we really realized that we had a gap here. And the way to fill it was with a mission like this. So in a lot of the meetings that we were having towards exploration in general, including Mars, were that we had to reduce the mass of the food system. And the food system is one of the greatest mass drivers on a human mission for human logistics. And we are going to be resource-constrained on these missions. So we are always challenged with reducing that mass. Well, the food system is connected to every aspect of health and performance in the human. So, the nutrients that we’re intaking, the food that we’re eating is impacting every system in our body and the resulting health and performance of every system. And so, in order to have a high-performing astronaut who can complete all of their mission tasks, you want to be feeding them adequately to perform those tasks.

When you start talking about cutting mass of a food system, that can become a challenge. If you look through the history of exploration, it has always been a challenge. Even going to the Arctic and the Antarctic, the logistics of carrying that food with them has often been the reason for success or failure. So, the resulting food system that they did choose to bring would impact whether that mission was successful, whether that mission failed, and whether they even lost human life. So, we really want to make sure that when we’re going on these missions, we understand if we do make cuts, what that means to our crew health and performance. And when we would have these conversations and we would talk about, “okay, well if we cut this system, it could impact their health, it could impact their performance, it could impact mission objectives…” The question was always, well, where is that line? How much is it impacting? What does that look like cognitively and physically? And we really needed more data; there’s really not a lot of data that’s out there that directly shows that correlation between food intake, cognitive performance, physical performance and health through a mission like this when you’re in that resource-constrained environment. So, we really needed better data and understanding what that meant with a Mars-realistic food system.

So that was the basis for starting to put this together; and really, this became a very integrated evaluation of health and performance that we’re getting a lot of data in different areas. So, we are getting very important food system data. We are also getting very important data in other aspects of health and performance. We have several experts that are part of this. We have behavioral health and performance. We have exercise, we have EVA physiology, immunology, nutritional biochemistry. We have co-investigators in all of these areas who have worked on integrating how we’re putting this mission together and how we’re collecting this data so that we can really understand as we’re going through this whole year in this Mars-realistic resource-constrained environment what we think a Mars-realistic food system will actually look like; how we’re supporting that health and performance so that we can provide that data to those mission planners so that they can make really accurate trades between risks to crew health and performance and the resources that they’re taking on those missions, such as the food system, and whether we can reduce that mass and still support crew adequately. So that’s really what we’re trying to get before we design the vehicles that have to take those supplies.

Host: Yeah. People were asking you for the data, show me the data as to why you need this much. And you said, “all right, well, you know what, let’s go get that data.” And what you talked about is it kind of started with this idea of you were trying to answer the questions of food systems, but it became so much more expansive, right? And your involvement with the food system even goes beyond that. You have more of a background in various other sciences to allow you to integrate and pull in different experts, so exactly the same questions that are being asked of you, “show me the data?” other scientists and different disciplines are being asked the same question. This is everybody’s chance to have good data to support a good mission design from ours.

Grace Douglas: Well, and even beyond that, the real core is it is integrated. So, actually from day one, when we were looking at, okay, we have to understand how this food system is impacting, it is already an integrated health and performance data set that we’re looking for. But we need to bring in all the experts together to get that integrated health and performance dataset. So, they need that data as well, but it is all connected and integrated, and that’s what we’ve been able to do, actually pull all that together in an integrated data plan so that we can collect that data in that way. It is giving us all of that data, but really, we needed to connect it together. We needed to collect it over that same timeframe where we could connect it and be able to understand how we’re impacting, you know, the EVA performance, how we’re impacting the exercise performance. Then they’re getting the same data through this mission. Is the exercise that they’re planning going to support the crew through these missions, too? So it is all integrated, but based on how we set it up, how we’re taking that data, how we’re going to statistically analyze it—we have a Biostatistician who’s also part of our team—and then how we analyze that data, it’s going to give us those answers on how those things are associated. Are we seeing decrements that could be related to food intake in a certain area? Potentially we could see the decrement and it could be related to something else. And that’s part of the reason we really need to do multiple missions because we’re keeping the missions very consistent throughout. We’re changing a few factors in how we’re going through the missions so that across a couple of missions, across a couple of different crews, we can start to understand what’s actually impacting. We’re going to be able to go deeper than “is it just a time impact—a time and mission impact?” based on how we’re designing the multiple missions.

Host: Tell me about the process of the integration, right? I guess you were central in that, in bringing all the different disciplines together. So, when someone asks you like, “what is the CHAPEA science?” And you tried to capture all the different disciplines that are trying to find good data and how that all is integrated and works together. How do you describe it?

Grace Douglas: Okay. So we do have an integrated team that includes the food system which is set up to be more Mars-realistic. So unlike on the International Space Station where they get regular resupply and then do get some fresh fruits and vegetables on some of those resupply missions, and they get a lot of crew choice on those missions, too. So maybe 20-25% of the foods that they’re getting are foods that they personally were able to choose. Versus on a mission to Mars, we might have to pre-position foods ahead of crew arrival, which might mean it might be ahead of crew selection. There could even be crew changes between the time of sending the food and the crew getting there. So, if we were to provide preference, it might not be the crew members we think showing up to consume that food.

So we do use most of the menu right now on the International Space Station as a standard menu for that reason because we found in the past that when you’re not sending food with the crew, it’s better to have a lot of choice and variety so that they hopefully are being able to pick what they want and get the nutrition that they need. Versus sending preference that might not be that crew member’s preference because if you really like something and you pick to eat it a lot every single week, and then another crew member gets switched in who really didn’t like that food, then they might avoid that food and they’re better off having a lot of choice and hopefully finding things they like rather than having a lot of the same thing that another crew member chose.

That’s why even on the International Space Station, we can only send some preference because it gets resupplied. And a lot of the food is sent ahead of when the crew gets there. So for Mars, this gets even more challenging because based on the planetary physics, we might have to send all the food ahead and there won’t be resupply. There won’t be any fresh fruits and vegetables coming that way. So we need to understand if we only have a standard menu, how do we support crew with that if they’re not going to get preference? So we’ve set up what we believe will be a Mars-realistic menu, with a Mars-realistic resource usage. And we have set that up for a year. And within that, we do have some phases where the crew will get the opportunity to grow some crops, which would be in place of getting the fresh food supply and we’re going to collect data on that too, because right now there are some experiments on the International Space Station where crew get to do stuff like that. But it’s not a part of everyday or of regular food consumption. Now this is still supplemental. There’s a lot of challenges when you start growing crops on a mission that still need to be solved, but we really need to start solving those now too and understanding that if we’re going to start including bioregenerative systems more and start relying on them at some point. And we have a co-investigator from the Kennedy Space Center who is working on the crop growth part of our plan. Again, it’s a large group of experts who are part of this.

In relation to how that’s set up through the year, we have a lot of investigators taking that health and performance data that’s critical. It’s critical for them to understand how Mars-realistic resources are impacting their systems. And that includes all the stresses involved. So they’re in isolation and confinement. They have a significant time delay and that’s very Mars-realistic to having that time delay for communications because they’re not going to be able to talk to Mission Control in real-time. And then also we have restrictions on other resources. Within all of those restrictions, we can capture how the crew’s doing over that year. We are collecting all of their dietary intake throughout so we can understand how their nutritional intake is impacting their health. So we’re taking a lot of biological samples, you know, stool, blood, saliva, urine. We’re taking a lot performance data from exercise and we are taking performance data from the EVAs that they’re going to go on out in their sandbox. We will be getting cognitive data as well, so that throughout that mission, we can start really understanding the associations of those things by collecting large amounts of data in all of those areas throughout that mission. And we do not have the opportunity to collect a lot of that data together on the International Space Station. There’s always a lot of experiments going on. There are very few crew members so to be able to get that data in that integrated way is very unique. And being able to look at it for that length of a mission is going to give us a lot of really important information on how all of those things are relating and how all of those things are supporting each other. We’re also collecting the team performance data, so we have experts from behavioral health and performance who are part of our team. Experts from Immunology who will be collecting that immunological data from those biological samples, from Nutritional Biochemistry who will be collecting their nutritional status from those samples, and we have a Biostatistician who will be helping us integrate all of that throughout the mission.

Host: Okay. So, if you were to think about the analysis process, so I’m trying to get into the mind of an investigator for CHAPEA, and you said part of the idea of CHAPEA is its repeatability. You take this formula, you put it towards one mission, and then you do it towards future missions, so you have a really good sample size and set. When it comes to the data collection and analysis starting now, you know, I feel like as a scientist—I’m not a scientist—but if I were, I would be eager. I would be one to go right in and start analyzing some of that stuff, but maybe you have to hold off for a little bit. What is the process of being a scientist for CHAPEA and collecting that information, logging it, taking a look at it? What does that process look like for all of the different disciplines? Is it mostly logging here in the

near term and then you get to the analysis for some of the future missions? What does that look like?

Grace Douglas: So a lot of it at this point is collecting the data, and we do check it and make sure everything’s looking good as we’re going through the mission. And then a lot of the analysis will happen later once we start getting that data over multiple points. Then of course, there’ll be another integration at the end of all the missions. So it will take a while to get all that data put together.

Host: Yeah. But this is the place to do it. It is this analog, right? You said you can’t really try it on the International Space Station just because the operations don’t fit for a year-long, let’s send a year’s worth of food and see how things work. The analog really helps us to set a scene that is most Mars-like that allows us to strategically gather the data in a way that is predictable and controllable. This is the way to do it.

Grace Douglas: There’s actually a lot of reasons to use an analog. One is that we can make this more Mars-realistic. We can have that time delay with the isolation and confinements. We can go on the sequence of EVAs that’s much more Mars-realistic in a sandbox than what we’d be able to do with the International Space Station, which has their scheduled EVAs, which are not on a Mars-expected sequence right now. So what we really want to do is understand that in that Mars-restricted environment. The other thing is ISS (International Space Station) is regularly resupplied and we’re probably not going to really be able to resupply a Mars mission because of the planetary physics. So, we are able to set up more restricted resources, that more restricted food system. We have more restrictions on our other resources as well. What is on this Mars planet is there now for them to use and they won’t be able to just get other resources in the next resupply mission.

So we want to make sure that how we’re supporting them is adequate. In addition to that, there are limited opportunities to be able to collect large amounts of data like this on the International Space Station because, you know, we have only so many crew that can go on the International Space Station and there’s a lot of experiments that want to get done on the International Space Station. So having this analog environment allows us to put in some of the other realism effects which we might not get on the International Space Station and it also allows us to get a larger sample size looking specifically at the large amounts of data that we are going to need to really be able to answer this question where we can have more analogs on Earth, and we have one International Space Station. So, it really offers us that opportunity to collect more science that will get us to Mars faster and with a lot more knowledge to make sure that this mission will be successful.

Host: Yeah. As a scientist yourself, you want the best information that you can have to come up with a good plan. And you’re thinking from the food system and there’s also, you know, you mentioned the many other disciplines and getting buy-in into this mission because I feel like there was a sense of desire for exactly what you were seeking. And I wonder if you can relay working and being and integrating a lot of the science, what you have experienced with working with some of the scientists. Is there a sense of excitement, eagerness? Are folks really looking forward to this for the years to come and see this repeated data? What’s your sense, being there, you know, working with the scientists day in and day out? What is their sense of excitement towards this mission?

Grace Douglas: I would say that everybody’s really excited. From the very beginning, there was a strong support from the science and engineering teams who saw that we really needed to start collecting data in this direction to start informing those missions. And this was really a missing piece that we were getting challenged with these resource restrictions without having a really good sense of what that meant to the crew impact. And we really need to be able to understand that trade that we’re making before we go on those missions. So right from the beginning, everybody was very excited when we started moving in this direction. All of our co-investigators were very excited to get on board with this project and to put together this integrated design and have been amazing in their efforts throughout. So that goes even beyond our science team to the engineering team who’s helped us build this analog and build this mission. And our Mission Control team, everybody has just been very excited and, you know, even in the weeks leading up to that mission, the crew has said that they had a very intense training and we were all part of that very intense training. Everybody was there for very long hours, but very excited to be part of moving forward in the direction of “this is going to get us data that we need to be successful on a Mars mission,” to move forward strongly in that direction. So there’s been a lot of excitement.

Host: It’s inspiring to the scientific community, I bet. But I also know that, you know, we talked about this mission before the mission actually happened, but from what I read, from what I saw, the interest in participation in human research analogs spiked because of this effort. A lot went into it. And as soon as there was an ingress, other analogs, especially here at the Johnson Space Center, like HERA (Human Exploration Research Analog)—a very similar study on a much shorter duration—you had an increase, an influx and desire and applications to be a part of that. So that’s got to be exciting, too. There’s interest not only in the scientific community but in the participation of being a person to contribute to a better understanding of humans on Mars.

Grace Douglas: Yes, and I can say I cannot be more thankful for all those individuals who are willing to participate as volunteers in analog science because this really is the core of getting us all of the data that we’re going to need to go on these missions. Thank you.

Host: Yes. And even talking with the crew, all of them had that passion to contribute to the greater good. I remember particularly talking with Anca, I thought her response was very interesting when we talked with her on episode 295. She said she was thinking 5,000 years in the future and wanted to be able to contribute to humanity’s progress. I was just like, “Anca, that is a crazy amount of time. I wouldn’t even be able to conceptualize that.” But for her to have that ambition to contribute to something that can be attributed to something so far in the future, that’s the kind of folks that you’re getting into this. So it’s got to feel really good.

Grace Douglas: Yes; and again, I just want to thank all of our volunteers in this mission. They’re an incredible crew and we are very grateful for having such elite scientists and engineers be part of our missions.

Host: Yeah. That has got to feel good. And so all the best to you, Grace, and the team that has worked so hard to get CHAPEA off the ground and running, and we’re in it now. We’re actually executing the mission. We’re thinking about the next one. We’re getting the science. This is all very interesting stuff. Grace Douglas, thank you so much for sharing some of the science that’s happening on CHAPEA. I appreciate your time.

Grace Douglas: Thank you.

Host: Okay and last but not least, the last two crew members recorded their experience together. This is Medical Officer, Nathan Jones, and Science Officer, Anca Selariu.

Anca Selariu: Hi, my name is Anca Selariu. I’m the science officer on the CHAPEA mission.

Nathan Jones: Hi there. My name is Nathan Jones, I’m the medical officer on CHAPEA 1.

Anca Selariu: Hi Nate. How are you feeling right now?

Nathan Jones: Yeah, so, pretty relaxed right now. I’ve been feeling good. How about yourself, Anca?

Anca Selariu: I’m filled with joy and wonder to be here [laughs].

Nathan Jones: Alright. Well, I’m going to go on with the next question. It says, “tell us about the moment you walked through the hatch and began the mission.”

Anca Selariu: You go, Nate.

Nathan Jones: Okay. Well, I guess I’ll answer the question. I think we all basically walked in, they closed the door on us and we kind of stood there for a moment looking at each other and kind of just kind of started cheering, kind of embrace each other arm in arm, you know, and kind of stood in a circle and just said some encouraging things to each other.

Anca Selariu: Right. For me, it was really like we walked into a dream. It was all very surreal, especially after that intense and emotional ingress.

Nathan Jones: Yeah, it was emotional. I took a little flack from my family, I think I cried just a little bit whenever I was thanking my family.

Anca Selariu: Hey Nate, what did you do? The first thing after entering.

Nathan Jones: We basically went to our rooms after that little group moment and unpacked our things. And that’s just about all we did the first evening I would say. How about you?

Anca Selariu: Yeah. But after we each got into our rooms and sorted out our stuff, we realized that we were finally hungry because all day we were thinking “before ingress, we really should eat something special that we were about to miss for a year,” but none of us could ingest much that day. So we finally did at night.

Nathan Jones: Yeah, I think it was an interesting evening and probably the next day too, or a lot of us just walking around like, “I can’t believe we’re actually here.” Sort of going back and forth amongst ourselves. Anca, how was the first night’s sleep?

Anca Selariu: I slept like a baby for the first time in nearly a month. The bed was probably the most comfortable I had in years, but I’ve been in many places of this world. How was it for you?

Nathan Jones: I’d say it was fine. There wasn’t much to note. The beds weren’t terribly amazing. They’re kind of twin-sized beds, so about what you’d find in a dorm. It was a bit humid in the rooms I think when we woke up, so I think we all woke up feeling a bit warm. But otherwise, it was fine.

Anca Selariu:How do you feel about the food, Nate?

Nathan Jones: I think the food’s pretty good. It’s the same thing that the astronauts eat on the International Space Station for the most part. They actually get maybe a little bit more fresh foods due to the fact that they have a bunch of resupply missions. But we have a good variety and it usually keeps us from getting too bored of most foods. We also get a special meal on Saturday nights every week. We had tacos one Saturday, I think Indian food this past weekend. They always keep it just a little bit more interesting.

Anca Selariu: Yeah. As for me, I think the crew’s already tired of hearing me marvel at the foods, how much variety that there is and how tasty I find most things, which is not easy to achieve as my friends on Earth often note. It’s also very surprising that I don’t actually miss a whole lot. Just a couple crunchy stuff. That’s it.

[Laughs]

Nathan Jones: Yeah, I’d say I probably miss eating chips and some of those crunchy sorts of things, and maybe popcorn. Anca, what tasks do they have us doing?

Anca Selariu: We do everything you would expect an astronaut to do. Perform maintenance tasks inside and outside the habitat, execute Extravehicular Activities, do inventory, track every item, keep detailed records of everything that we do, fill out a lot of surveys that inform every science arm of the CHAPEA mission to integrate data from exercise, behavioral health, microbiology, immunology, food and crop systems.

Nathan Jones: I say that pretty well sums it up, yeah. Are the first few weeks in line with what you expected them to be like? I’d say pretty close. I always suspect that NASA would have a hard time keeping us busy. I’d say we’re all pretty—

Anca Selariu: High functioning.

[Laughs]

Nathan Jones: High functioning and hard workers. Pretty efficient people in general, which is what allowed us to do many things that we’ve done that qualified us to be on the mission. So, we tend to get things done pretty quickly, I think. And that keeps them on their toes at Mission Control.

Anca Selariu:Yeah, I agree. I think our learning curve was shorter than we actually anticipated. So the only thing that is unusual for me is that I’m slightly giddier than I am on Earth.

Nathan Jones: Okay.

Anca Selariu: But that’s it. What is in line with your expectation and what is more of a surprise?

Nathan Jones: I’d say we’ve had quite a few issues pop up already, mostly IT-related. We’ve been able to solve many of them, if not all of them eventually. I know that I have a decent background in IT, and it’s definitely been helpful to know how to code. And so I’ve been able to use that a bit more than I ever expected to.

Anca Selariu: Well, expectations for me are a fairly tricky thing. We were eager to start using the schedule and experience that famous red line by which we are to live our lives. The delay is really interesting. It really makes the experience of time different in a way that I’m still trying to wrap my brain around. But the most pleasant surprise was how easily we fit together to do our tasks. You’d imagine them putting “strangers”—because we don’t feel like strangers to one another—putting strangers together necessarily would create tension. But we’re getting into week four with all of our wits about us and we still laugh together and we seek each other’s company and still have fun. So, good [laughs].

Nathan Jones: Yeah.

Anca Selariu: What’s coming up in the next month, Nate?

Nathan Jones: I haven’t really looked forward to the next month. I’m more of a “taking it one day at a time” sort of person. So, I do know that this week we’re doing a lot of fitness testing and sample collections and they’re going to use those to compare to future testing and past testing that they’ve done on us. That’s about it.

Anca Selariu: Right. And I am very much like you, Nate. I love watching the days rolling by and I take things as they come. I do look forward to the crops though. I really can’t wait to actually see plants and talk to them and pet them every now and then. And hopefully even eat them [laughs].

Nathan Jones: That will be good. We can get ’em to that point. Well, I think that’s all the questions we had to answer for now. We appreciate everyone’s time and we hope that you all have a good week.

Anca Selariu: And think of Mars!

[Music]

Host: Hey, thanks for sticking around. Super fun to hear from all of the crew members inside CHAPEA. Great to know that they are off to a fantastic start. Cannot wait for the next one, and I hope you learn something today. You can check out NASA.gov for periodic updates on their progress, and of course, keep listening to us. We’re going to be doing these audio logs monthly. This is the first in our series.

If you want to check out more podcasts, we’re at NASA.gov/podcasts. You can click on us, Houston We Have a Podcast, or any of the other great shows we have across the agency. If you navigate to us, you can listen to any of our podcasts in no particular order. If you want to talk to us, we’re on social media. We are on the Facebook, X, and Instagram pages of the NASA Johnson Space Center, and you can use #AskNASA on any one of those platforms to submit an idea for the show. Just make sure to mention it’s for us at Houston We Have a Podcast. Recordings were sent from the CHAPEA crew through July and we had the conversation with Grace on August 2, 2023. Thanks to Will Flato, Dane Turner, Abby Graf, Belinda Pulido, Jaden Jennings, and Anna Schneider. Thanks to Grace Douglas for taking the time to come on the show and big thanks to Kelly Haston, Ross Brockwell, Nathan Jones, and Anca Selariu for sharing their experience for this audience on Houston We Have a Podcast. Give us a rating and feedback on whatever platform you’re listening to us on and tell us what you think of our podcast. We’ll be back next week.