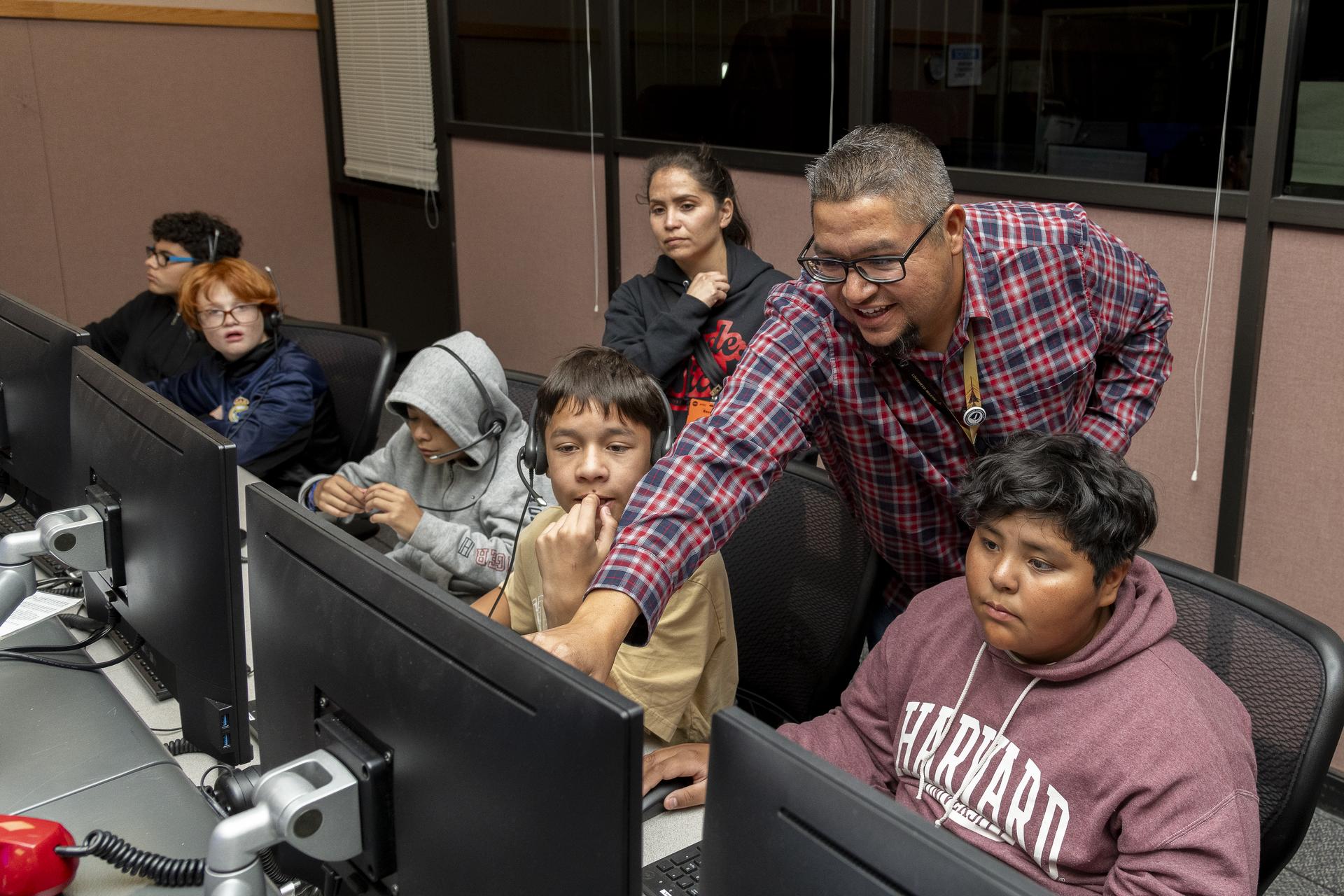

From Earth orbit to the Moon and Mars, explore the world of human spaceflight with NASA each week on the official podcast of the Johnson Space Center in Houston, Texas. Listen to in-depth conversations with the astronauts, scientists and engineers who make it possible.

On episode 361, former NASA flight director Gerry Griffin discusses his trailblazing career in the agency and his experience leading multiple Apollo missions, including the final lunar landing on Apollo 17. This episode was recorded on Aug. 16, 2024.

Transcript

Host (Leah Cheshier): Houston, we have a podcast! Welcome to the official podcast of the NASA Johnson Space Center, Episode 361, “Call Sign: Gold Flight.” I’m Leah Cheshier and I’ll be your host today. On this podcast, we bring in the experts, scientists, engineers, and astronauts, all to let you know what’s going on in the world of human spaceflight and more. The foundations of human space exploration as we know it today were born at Johnson Space Center and it’s one of the greatest honors to speak with some of the trailblazers who helped open the skies to us forever.

Today’s guest is a one-of-a-kind NASA icon with experience at all levels of the agency. Gerry Griffin started his career in the U.S. Air Force, later joining NASA in 1964 as a flight controller. He became a flight director where he led multiple Apollo missions, including the final lunar landing on Apollo 17. He also served as Deputy Director of Kennedy Space Center and Dryden Flight Research Center, now known as Armstrong. At NASA Headquarters in Washington, D.C., Gerry also held the posts of Assistant Administrator for Legislative Affairs, Associate Administrator for External Relations, and Deputy Associate Administrator for Spaceflight. He rounded out his NASA career by coming back to his home state of Texas and serving as the Center Director of our very own Johnson Space Center. Let’s get started.

[Music]

Host: Gerry, thank you so much for joining us today on Houston We Have a Podcast.

Gerry Griffin: Well, glad to be here.

Host: Yeah. It means a lot to have you just come out and sit down and talk about the good old days and what you’ve been up to lately.

Gerry Griffin: Okay. I’m ready.

Host: So let’s rewind a little bit. When you joined the Air Force, did you have any idea that someday you might work for NASA?

Gerry Griffin: No, I didn’t. And the reason was there was no NASA when I joined the Air Force. I had graduated from A&M in ‘56, got commissioned and got called active duty in late 1956. Well, I was in a fighter squadron out in California, and NASA got formed in ‘58 and officially became an agency in October of ‘58. And I was still in the fighter squadron and still had active duty left to go. But I thought, golly, they’re going to the Moon. You know, that’s their purpose, right? I said, “Yeah, I wonder if I could get in there.” But I couldn’t right away. I had to finish my obligation. But as soon as I could see the end of my active-duty commitment, which was four years, I started knocking on the door, just to test it. And of course, they were at the time in the middle of Mercury. And they were busier than heck. But I talked to, I didn’t talk to Kranz the first time. I talked to a fellow named Jim Tomberlin who worked for Kranz, and he said, he said, “Hey, we like your background, but hold on. We’ve got to get through Mercury here right now.” And so I bided my time, I went ahead and got out when I could, so I could get into the business as quickly as I could. So I joined the Lockheed Martin. Well, it wasn’t Lockheed Martin. It was Lockheed Michelin Space in Sunnyvale, California, which was classified stuff. Early early spy satellites. But it used Agena as an upper stage on the Thor vehicle, which later became Delta. So I learned a lot about satellites. Remember too, I was an aeronautical engineer. I didn’t know anything about how you did orbits and—

Host: Right.

Gerry Griffin: How you adjusted them and that kind of thing. And so that was a good learning experience for me. And I kept knocking on the door. I accused Kranz sometimes of low balling me with the first offer. And I thought I was worth more than that.

[Laughs]

Host: I’m sure you were.

Gerry Griffin: But he finally turned it over to a guy that needed an Agena person. Cause we were going to dock the Johnny with Agena vehicle. And so anyway, long story short, I finally took a pay cut and came to work and got here in 1964.

Host: So, with that background, you mentioned you were an aeronautical engineer, you had that degree, and then you were in the military. Did you ever think about being an astronaut?

Gerry Griffin: Yeah. I’m thinking about being an astronaut today. I’d like to, but realistically, in those days, and there was good reason for it. I think really, if you look at them, they were all test pilots. High performance airplanes, one-of-a-kind airplanes, right? First flight of one kind of an airplane. Very used to high-risk kind of activities that involved new kinds of technology. So there was no way. And now when I got into Mission Control, I went immediately and never worked on the Agena cause as soon as I got there, they looked at my background and said, “We’d like to have you in Gemini and be a flight controller.” So that’s what I became immediately.

I never thought I’d be a flight director even. I figured, well, they’ve probably got a, you know, they got some good people in there like Kranz and eventually Lunny, Charlesworth, and John Hodge and Kraft for a while. And then he dropped out. But, well, he got moved up. He got moved up to the head of, we called that FOD then. And then I think it went MOD and now we’re back to FOD. So anyway, it was a busy time. It was kind of quiet here. And when I first got here, we were spread out all over Houston. The center wasn’t quite complete. So, I got here in sometime like April or May, and I think we started moving in the fall of ‘64. We started moving into this center, brand new, little bitty trees planted all over the place. And now we got these huge trees. But it was really exciting time for me because I had finally gotten to human spaceflight. And to me, that was what it was going to be about and trying to get to the Moon.

Host: Right. And you mentioned coming in at the end of Mercury, and as we’re getting into the Gemini Program, and I know that being in between programs, it can come with a lot of unknowns. So what was that like? Was everybody really charging forward with Gemini? Were people nervous? What was that atmosphere?

Gerry Griffin: As I alluded to, it was kind of calm. For one thing, the same contractor built the Gemini spacecraft, built the Mercury, McDonnell. And they were kind of similar. The Gemini was much more technologically advanced, had fuel cells and things like that. But there was a similarity that I think made people a little bit comfortable, maybe more comfortable. There was less comfort when we went to Apollo and a different contractor and a different kind of spacecraft that had to go to the Moon, not just north of the orbit. And so it was, and the one thing I noticed right away, it was very professional. It was fun. We were all young. I was a little older than quite a few people cause my military time, but I was only when I got here, I think I was 29.

And when I became a flight director later, I was all of 33. But that’s where I got my grounding. I was first up in the Stall Myers building, which later became a warehouse. It was up on up 45 almost to Houston. And met some of the guys that I went, all of Gemini and most of Apollo, man, they made it through most of Apollo. So, great people.

And I’ll throw in something here that I think is overlooked quite often, what we did in that era of the ‘60s, particularly in into the early ‘70s, we couldn’t have done it without the spouses. It was just incredible. They did the banking, they did fixing air conditioner. They had get the lawn mower, mow it themselves. And they were wonderful. It took the load off of us that were trying to learn how to get to the Moon and get them back. So I really think quite often, our spouses did never did get all of the adoration that they should have. We knew it. But nobody else did. And I suspect that they, you know, military wives and significant others, had all always probably been there for them. But this was kind of a new ball game, and we were learning, learning, learning all the time. So, you know, we didn’t get to see many little league games or brownie meetings or anything like that. Even school activities. We didn’t get to see a lot of those.

Host: Yeah. I think everybody believed in the mission. Everybody knew how important it was. Not just for you all, you know, as you’re trying to do something new, but for the world and for America.

Gerry Griffin: And particularly for the country. And you’re exactly right. It was, you know, we never thought about, I say we never, we didn’t worry too much about the Soviet Union. We didn’t have time.

Host: Yeah. You were too busy working.

Gerry Griffin: Yeah. We had you a little bit like football teams. You can’t worry about the other team. You’ve got to make on the offense. You’ve got to make sure you’re doing what you’re supposed to do. And you just don’t have time to say, well, you know, that defense is let the coaches do that. The players and the coaches in this case were somewhere in Washington. They will let them worry about the Soviet Union and we’re going to get there as fast as we can. As safely as we can. And that it was fairly simple mission. And nobody wavered from it.

Host: Incredible. I want to go back and I’m going to have to read this because your career to me, I call it the tour of NASA in my mind. So you are—

Gerry Griffin: Couldn’t hold a job.

[Laughs]

Host: Yeah. I don’t know about that. You were the Deputy Director at Kennedy, also at Armstrong. And then you became the Center Director at JSC. It was the Manned Spacecraft Center back then, correct?

Gerry Griffin: Yep, but no, it was already the Johnson. That was already the Johnson Space Center by the time I came back. Because I got here in ‘82.

Host: Oh, got it. Yes. Okay. You also had a lot of different roles at NASA Headquarters. So each of those, all of our centers are connected. We say we are one NASA, but each of them has different programs, different challenges of their own. So what was it like having such a broad view of NASA by working in all of those roles? What was challenging about that? What came easy because of it? I would love to hear your perspective on that.

Gerry Griffin: I had grown up in the JSC culture. And it was really all I knew. Although I had visited other centers, but you know, we were the people on the street. One of the first things I found out is how strong all of the centers were, how good they were. Kennedy, Marshall, Langley, even Lewis, and now Glenn, JPL, which was a contractor, but good. And Ames and all the old flight research and all that. Gosh, the guys were good. They were all good. And I got to work with all of them at Headquarters. I got to know the Center Directors of these other centers. The big thing I had to learn right away was how you deal with the Congress. Cause I was brand new to that. And we were trying to, George Low, who had by that time, had become the Deputy Administrator and George, between George and Bill Anders, who was running the Space Council at that time, Former Apollo 8 astronaut that we recently lost in a plane crash. And by the way, Bill and I were in that same fighter squadron before NASA. We were in the same fighter squadron. and flew together and all that. We had no idea there would ever be a NASA or that he’d go to the Moon on Apollo 8. And, actually, I stayed very, very good friends with him almost till the day he died. But working with the Congress also took me, I ended up having to spend time with George. And I called on almost every congressman in the whole thing. All 535. And we tried, we spoke to our, we were trying to save the shuttle cause it almost got killed. And they wanted somebody that understood the technical stuff, which I did. And they also wanted somebody that could, as George said, can put one word in front of another and make sense out of it. So that’s why I ended up there.

But I had to start from scratch. And I had these two wonderful deputies, both of them. One of them later became the head of the U.S. Patent Office. He was an attorney, and the other one became the head of CSX Railroad. Both of them were great guys. They knew the Hill inside and out. They took me to the right people. They taught me that the staff is often just as important, maybe more important than the member of Congress. You’ve got to get to know them and how to work them a little bit. So it was a great learning experience. And I also learned that not everybody had the same view of JSC as I did. In those years, of course we had the astronauts, we had Mission Control. Our part of the mission lasted days to get to the Moon and back. The Kennedy job, for instance, always was huge, but it was over at liftoff.

Host: That’s true.

Gerry Griffin: And they went on to other, they had to go on to the next mission. So they never got the ink they deserved. And Marshall didn’t either, probably, at least they felt they didn’t. So, I just stored that away, that, you know, this is a great agency with a lot of strength, and JSC is no doubt one of the best, maybe the best of them, but don’t sell those other short.

Host: Yeah.

Gerry Griffin: And that perspective, when I became, later became Center Director was I worked on that. I worked on that.

Host: Nice. Well, before all of this though, you were a flight director. You were Gold Flight.

Gerry Griffin: Oh, yeah.

Host: I had to dress for—

Gerry Griffin: I like it.

Host: The occasion. So, as a flight director though, you’re really much more ingrained in the day by day and the minute-by-minute action.

Gerry Griffin: And technical stuff, too. Yeah.

Host: Yeah. What’s it like to have to leave that behind kind of, and see it from a bigger picture when you’re working in leadership?

Gerry Griffin: It was hard, but it was fun. Because I have found throughout my life that when you’re learning is when I’m the happiest and I still like to learn things. Maybe we’ll talk in a minute about the movies. And that was a new thing that I had to learn, how to cope with it. And, in my opinion of it changed by the way. But really, I think the hardest thing to do in all of that is trying to engulf it all. And when I say that, I mean, you not only have the Congress and the OMB and the White House and all that, and then never had that when I was a flight director, flight director in those days, particularly, was very key person in the control center, did all the final go, no go’s with a lot of help. They didn’t do it, and I didn’t do it on my own, but it took a lot of people to pull it off and do it right.

The flight director job, if I look back at everything I did, and it was a great honor to be the director here. But my favorite job was being a flight director in mission control during Apollo. It was so challenging. And I tell people, you’ll see pictures of us where we looked very worried and all that. Overall, it was a hoot. It was so much fun involved with it. Very challenging. But everybody in that control center, and most of the people around the whole network of NASA, they liked that challenge. That’s what they were there for. And pushing back that barrier to get to the Moon was by golly, we can do this. And after we flew Apollo 8 particularly, I think we all felt we may be able to pull this off. But of course, we hadn’t done it yet. And so anyway, it was a big shock going from a technical, very much day to day operation to this, it was day to day at when I was in Washington, but golly, it was at tiring. Oh, start at 7 in the morning and come home at 7 at night. And literally in Washington, you could go to a reception every night on the Hill for somebody, for some purpose. And my wife and I went to a couple of state dinners at the White House. And, you know, after about four years, I thought to myself, how many more times am I going to go through this cycle and all that? And finally, I went to my bosses and said, I think I’ve had about enough of Washington. I want to go somewhere where they’re doing something rather than talking about it. And they were very kind and they said, “Hey, we just happened to have an opening at Armstrong,” or well, Dryden Flight Research Center then. And I said, “Done, I’m gone, if that’s where you want me to go.” And I was just there a short time and then went to the Cape at Kennedy. But all of those years got all kind of like putting in a mix master and got stirred up and stirred together. And I used bits and pieces of it for the rest of my career. I still do today. I know how to work the Hill. You know, at least I’ve been there. And when somebody tells me that so and so is doing something, I say, “Okay, well let’s figure that out.” And so I think the other thing that it did moving away from the control center, and I don’t mean this to put the control center down, but it broke me out of the pack. I got visibility that you couldn’t get just, you know, keeping at it. I highly admire the people that stuck with it and stuck through it through shuttle and early ISS and they were good. But it just was not in my DNA probably to stay in the same job. I wanted to try to find things and learn.

Host: Well, let’s talk a little bit about those flight director days. You were the lead flight director for Apollo 17. What was it like? I mean, at that point you knew that was the last mission to the Moon in the Apollo program. How did that feel?

Gerry Griffin: Well, it was interesting. At first, you know, when they cut 20, I think, and then they cut 19 and 18. So we knew 17 was going to be it. At first, I was, well, dang. You know, we were really hitting our stride by the time we got to 17 on exploration as opposed to transportation only, which we had to do in the early days. Just make sure we could get out there and get back. Then I thought differently. I said, “Well, maybe it is time.”

And I never will forget a conversation. We were coming back from the Moon on Apollo 17. We were coasting back to Earth, and things were quiet. The crew was asleep. And the guys, quite often this would happen, the guys in the control center kind of stood up and, you know, shake a leg and all that. And a group of them, most of them, came up around my console and there was a little bit of, well flight, this is it. You know, we were getting toward our last shift. And in fact, that may have been our last shift. And because somebody else did the entry. And I said, yeah. And I stood up with them. I was sitting down, and they were all kind of hovering over me. And I stood up and I said, but you know, maybe it’s okay. 20 years from now we’ll be on Mars. That was 1972. That shows you what kind of predictor I am at big steps like that. But I really did think that we would move on much quicker. Back sending humans into deep space. Now, we did a lot in the ensuing years till we on the threshold of Artemis now. But we just didn’t do it. And our flight controllers and the people here at JSC that are in engineering and all that, they’re good, they’re good people, but they’ve not had that chance yet to break out a low Earth orbit. And, gosh, I hope they get it quickly.

Host: Me too. I want to be here for it so much. And thinking about that, you know, during Apollo 17, it’s been 50 years now. Did you think at that time that the engineering and the architecture and the things, the lessons learned from that, did you think that we would still be using those today as we’re preparing for this next giant leap?

Gerry Griffin: I thought a couple of things. That’s a great question because I thought a couple of things. One is perhaps the biggest legacy we left to Artemis now, or whoever came next, was the fact that it could be done. Cause when we started, we all, you know, we had the challenge and we were going for it, but we hadn’t done it yet. And I think if anything, what we’ve left shoulders to stand on is the fact that it can be done. And now there are a number of technical areas too that I think, in fact, the flight directors here now tell me. And so does Vanessa and others that, you know, without Apollo, there were a lot of questions that we answered. So now we’ve got to execute with Artemis. And that’s a good feeling to know that it can be done. And at certain, the technology is so much better now. And years of shuttle and years of ISS have helped that even, too. So, I think the things that we learned, everybody recognizes that they are valuable still. Of course, they happened a long time ago with different technologies and things like that. But I really think the people understand that had we not done Apollo, we might not have ever gone back. If we’d had a failure, unless somebody on the Moon or something like that, there may not have ever been a chance of getting back. So now at least we got the chance.

Host: I agree. And if we’d had a failure, there might not have been a NASA.

Gerry Griffin: That’s right. Could have been. Or it might have gone back to the research agency that NACA was before.

Host: I think the world would look a lot different. It would if we hadn’t had successful Apollo missions.

Gerry Griffin: Right.

Host: So let’s think Apollo 13, I mean, that was considered a successful failure essentially. You were going to be the flight director on console when we landed on the Moon. With Apollo 13. And pretty quickly that went out the window.

Gerry Griffin: It did. Yeah.

Host: This becomes a six-day mission when you have to figure out how to bring these guys home safe. How did everybody balance the work in that time? The all of a sudden, this is entirely different than what we predicted.

Gerry Griffin: Yeah. You know, the answer to every… I’ve been asked that before, and we did what we were trained to do. There was no panic, there was concern, of course. But we had always been trained to keep going as long as you have options. And we never ran out of them. We got kind of close, but we just kept playing away. We never discussed in the control center not getting them back. It never came up. Just that, okay, let’s go to work, figure this out. And it could have gone south on us, I guess, if certain things hadn’t worked as well as we thought they might. But the crew was great. The people on the ground were great. And this was a case where even if you look at the movie and most of the focus is on mission control, but the whole network of contractors and other centers and all of that jumped in to help us. So we had many, many people around the country working on Apollo 13 and down to the last decimal place. I mean, fine stuff. And so, they deserve a big chunk of that credit, too. We were the final decision makers. And after all that data was produced and all that, and then getting it up to the crew and what to do and how to do it. And so, it was what we were trained to do. If I had one, well, I’ll wait to talk about the movie till we get there cause there’s one thing that just irritated the heck out of me.

[Laughs]

Host: I can’t wait to hear it.

Gerry Griffin: Okay. But anyway, it was, Apollo 13 was, I think it was the term, “failure is not an option.” It was never used. That was later. And we never really did much agonizing. It was more just hard work and making sure we didn’t miss something.

Host: Right. Well, what was the pressure like after Apollo 13? Like I said, successful failure, essentially. What was the pressure like to make sure Apollo 14 as a comeback mission is successful?

Gerry Griffin: Well, that was a concern because, and just like after the fire, you have to give the leadership of the agency and the leadership of the country at the time that it wasn’t killed. And just said, you know, this is too dangerous. You know once they got once and the guys replicated the problem on the ground with the tank, there was no question that let’s fix it and fly 14. And the contractors set about to do that and we also added another oxygen tank on the other side of the service module. So in case the fixes didn’t work, we at least we’d have enough oxygen to get home just in case. So, you know, you just add a little more. But it was precise. And everybody felt, by the time we launched Apollo 14, I felt really good about it. And I did do the land and same place. We were going to go on 13. I did do the landing. I was a flight director for the landing on that one, my team. And it worked. So we got them off and brought them home.

Host: Mission accomplished.

Gerry Griffin: Mission accomplished.

Host: I was looking through, I have this book of beautiful restored photos from Apollo. And my dad and I were looking through it and he said, “Wow, I never realized the cadence of these missions and how quickly they were happening.” So what was that like on your side, having to prepare week after week for, was it multiple missions at a time? I’m assuming, you know, you may be in one mission and already planning two ahead. What’s that like?

Gerry Griffin: It was, tell you a quick anecdote that I I remember and it goes back to Apollo 11, and we put two flight directors on the launch, and I was with Cliff Charlesworth, and we were go in the countdown at the Cape, and we got to hold, a built in hold where everybody kind of looks at their data and says, “Yeah, we’re okay. We can go.” And so it was quiet for a minute, and I had already been named as lead flight director for 12. And I had already met with (Charles “Pete”) Conrad and (Alan L.) Bean and (Richard F.) Gordon. And we’d started flight plan stuff and all that. I am sitting there in the countdown for Apollo 11, our first landing mission. And I’m thinking to myself, okay, what have I got to do on 12 soon as we get launch here and get going? I’ve got to call so and so and so, and all of a sudden it dawned on me, hey, you dodo, get your head in this game. Not in the game that’s going to take place later. But that’s what the overlap was like, because we had to stay ahead of things.

We had six flight directors. And so by the time we got to Apollo, we only had six. So we were all tied up and busy and going around in circles. But it was a wonderful time. It was so neat. And particularly with the “J” missions, which were the last three missions that had a lot more capability than the first block of lunar modules and command modules. It really did. We were looking, I was looking really forward to those cause I thought, and I alluded to this earlier, that we were early on, we had to be, our major focus was to get the crew out to the Moon, get them back safely, and do what science we could. And by the time we got to 15, I think was the break, that was the first so-called “J” mission, I could sense a change, why we were more focused on why we were going and what we were going to do once we got there. Never taking our eyeballs off the systems and all that. But we learned how to kind of assimilate both. And a lot of that came about because several of us, well, I was the first one, but Dave Scott on 15 asked me to come out and go through some training with them on Earth, on lunar surface training. So I really got to see how the lunar scientists, talked to them and how they really taught them lunar science is what they did. And so they were very comfortable. And I remember Dave telling me one time, we never worried about our backpacks cause we know you guys were watching that. They would check them every once in a while. But he said, you know, we were just out on the surface doing our exploration work. And, so you could sense that all of this had started to change. We had the rover, and they could go a lot farther away and all that.

So I really think the shift came between 14 and 15 and that shift in thinking. And as more, I came back and I told Gene, I said, “We need to get some more guys out there in the field with the astronauts when they’re training on the learner surface stuff.” And he agreed. And he went, I think he had the same reaction. And met scientists from Caltech and all those places that were really neat people and USGA, the geological people. So it was, I really enjoyed those last three missions on the science side of it. And we had problems, we always had problems with those last three missions, but in fact, we almost didn’t land 14. We almost didn’t land on 16. There that were two of them that we really in 14, of course, was the Block I air spacecraft. So by the time we got through 15, 16, 17, hey, this works. You know, we know how to do it now. And I think there was that focus on the science that all of us were able to drag off some time and really focus on that.

Host: You called them the “J” Missions. What’s that stand for?

Gerry Griffin: That was just a, that was, it started, if you go back, it goes clear back to A’s, B’s and, and it was the type of missions. The “J” missions were a new block when they manufacture something like a lunar module, there were Block I and then they improved it. But they couldn’t just phase it in. They had to get it ready to go the Block II spacecraft. And at the end of 14, we went to Block II for the rest of those three missions. They were more capable. They could stay on the lunar module, for instance, could stay on the Moon longer. The command and service module had what we called a SIM, a Scientific Instrumentation Module that was continually mapping, well, the mothership stayed in orbit. It was continually mapping the Moon.

Host: Oh, that’s so interesting.

Gerry Griffin: So they got much better resolution from that than now it’s even better now with some robots. But that was kind of, and we had to bring the film back. And so it meant they had to do an EVA in very deep space, essentially on the way home, and went outside and got that film, brought it back in, and brought it back, and they developed it.

The one thing about Apollo that was really interesting in 13 was the greatest example is we didn’t have any way to upload information. We could upload computer updates and things like that a little bit. Not a whole lot, but we didn’t have any way to, for instance, the Apollo 13 checklist to repower the command service module after we had shut it down after the explosion had to be worked out on the ground, then we had to read it to him. And you know what Swigert told us later, Jack Swigert, who was writing it all down, I said, we need to put some tablets or something. He was looking for things to write on. He was using checklist back sheets and all that he was doing. And so we didn’t have any way to send up a lot of data at one time. And then when shuttle, we had the, I think it was called the teleprinter, which is essentially you could send them a document and just say, here’s the new checklist. But it was grassroots in the old days. And even with the final three missions, the Block II spacecraft, and that “J” is just the name of a mission. It doesn’t mean any, the “J” itself doesn’t stand for anything. And so it was really funny. Those last three missions were a hoot because we were into that lunar science a little more.

Host: Well, it’s funny you mentioned tablets, because that means something entirely different today. And we do have them on our flights.

Gerry Griffin: Yeah. Well, you know, and after the fire, I’m not sure which company it may have been somebody like 3M built a self-extinguishing paper that wouldn’t burn. Before the fire, we had a lot of paper inside and we couldn’t, and I’ve been told that that paper is now used in operating environments in hospitals where there’s a high oxygen content that where you have a little more, in the atmosphere of the room, have more oxygen available, then they use that kind of paper, it won’t ignite. It just goes out and—

Host: See, I wish more people knew that all the things that were developed for NASA that now have practical use.

Gerry Griffin: I hope that, like I say, I’ve heard that. And I’ve never had somebody say that we use it. They may not even know they’re using it. It’s paper.

Host: Right. That’s fascinating. I wouldn’t be surprised if that’s accurate.

Gerry Griffin: Could be.

Host: So 50 years later, about the same Moon. So what’s your advice for the future lunar flight directors?

Gerry Griffin: You know, I talk to some of them occasionally, and I talk to the head, Emily Nelson, now. And the main advice I give them is that it’s hard to get into space. And it’s hard to get to low Earth orbit, but there’s nothing like when you do trans-lunar injection, which is what we call the burn that sends you to the Moon, the maneuver has velocity enough to escape Earth. That’s a bit of a gulp moment. It’s the commitment cause now we’ve done it. We’ve committed them and we’ve got to get them back some way, by either through an abort or through a normal mission or whatever. But the crews’ lives are now on the line in a different fashion. At the Moon, you know, it’ll take you three-and-a-half, four days to get home. If you have a problem, unlike low Earth orbit, where I think from the ISS, it’s a matter of hours. They could abandon it and if they really had to fire or something. So I really think the bottom line to Artemis is that we’re ready to do it. It’s been done. We’ve got a great team of people. I think we’ve just got to turn them loose if we can. And that’s what we had in Apollo. They turned us loose and they trusted us, and we trusted them. And they had our back, and we had the air back and up and down, up and down the chain. That’s hard to maintain. Very long.

Host: It sounds so electric though. To work here in that time.

Gerry Griffin: Yeah. Oh, it was, yeah. A quick story on Apollo 13, that is the best indicator I can remember. Glynn Lunney and I, Gene Kranz was off trying to figure out what had happened in their shutdown and how to get the command module and get it and be able to later get it back on cause that never had been done in space. And so his team was up to here. So Glynn and my, Glynn Lunney was the black team, and I was the gold team. And both our teams had worked on what to do next. I was more focused on consumables, and Glynn was more on trajectory. And finally, at one point, and I listened to this transcript not too long ago, I called, well, Kraft had been in the control center quite a bit. So I just talked directly to him. I think we know what we want to do now. And I can’t remember either he said, or I said, we ought to get to senior management that’s here and at least brief them so they know what’s coming up. And so we went downstairs to the viewing room on the second floor, and the control center was shut down and there was hardly any lights on in the place, but it was a private place. And there were people there like Kraft and Gilruth and Rocco Petrone, Deke Slayton, and the administrator of NASA, a fellow named Tom Paine. Thomas Paine. And at there were some other people from other centers and I can’t remember. And we had some of our engineer, Max Faget was there, and there were some engineering people in room, probably maybe 15, 20 people max. So I briefed him on consumables and what it looked like, Glynn got up and explained several options on trajectory, and he finally got to the end of his discussion and he said, and the option we like is what we call PC+2, that’s pericynthion and that’s closest point of approach to the Moon plus two hours to do this maneuver with the decent stage on the lunar module and speed us up. It gets us back where we can get a carrier underneath it. And it, oh, Jim McDivitt was there. He was a program manager. We can get a carrier under them, so we’ll have a carrier, we can get them back faster about, I think it was 18 hours, we could get them back quicker. But we’ve got to burn that decent engine, you know, a long time to add that velocity. But that’s the one we like. And so then he just left it there and there was this long silence, not long, but it was awkward silence for a minute. Tom Paine, the head of the agency, said, “What can we do to help you men?” That’s all he said. There were no questions about did you think about or did you do this right, or did you do that? That’s where the leadership had trust in us. And so, that whole sequence kind of, and I didn’t recognize it at the time, but later on when I said, golly, how neat that was, big one of those guys raised a question right about, well, you want to burn the engine that long or already been decided it was okay.

Host: You’re the closest to it. They trusted that you knew the mission.

Gerry Griffin: And that’s the point that I think was the strength of NASA is because decisions, not just at JSC and during missions, but all over those decisions were pushed down to the level where the expertise was. And one of my points I make when I talk to corporations, cause it happens to corporations the same way. As they age, more decisions start going to the top, which slows things down. It costs money. And then you got, in often cases, you got people at the top trying to make decisions that don’t know much about except maybe the financial impact. But whether it’s a worthy way to go or whatever, they don’t have that.

And I can see it in NASA today that as the agency has aged, there’s more visibility and decisions coming out Headquarters about a very highly technical issue. I don’t think it’s the way to go. I think it’s inevitable unless you’re just very, very conscious of it and don’t let it happen. But it happens. And when I got into the private sector, and particularly when I was in the executive search business, I could see it in the biggest companies in the United States and what often happens, somebody will move up the chain of command and they take their decisions with them rather than leaving them with the people that they knew they should have readied to take that day. And so it’s something you’ve got to worry about and think about. I don’t think our people at Headquarters, for instance, I don’t think they ever wanted the decision-making process when it came to highly technical decisions now, you know, if it was money or something like that, of course. But I don’t think they liked, they knew that we were ready, that we knew what we were talking about. And that was that trust level, leadership can do that if they trust the people below them, hold us accountable. You know, if we screw up, something’s got to happen, but hold us accountable, but don’t try to make the decision yourself.

Host: Well, with that, I mean, you really rose up through the ranks at NASA starting as a flight controller and then all the way up to working at Headquarters and working as a Center Director. Do you think it’s important that leadership gets to see an organization from the bottom before being promoted to leadership?

Gerry Griffin: I do. Yeah. I do. And in fact, that’s a good point. When I went to take over legislative affairs, if I hadn’t trusted Mossinghoff and Bob Wood, I don’t know what I’d have done. Because they taught me how to do that and they never got out of it. They kept doing it themselves, too. So if there was something I didn’t understand, I’d say, “Bob, would you go talk to Senator Gluts and see if you can straighten him out?” Usually it was a lost cause. I said, and Mossinghoff a lost cause, I like to talk to the friends. But yeah, I think it is just something that every large organization needs to be conscious of, don’t try to do too much at the top. It slows things down. Part of that came about and understandably after the Challenger accident, more paper, more approvals, more this, more that. And that’s the price you pay when you have an accident. But it would be nice to see if you could shed that after a while and build that trust back and be like Apollo.

Host: Yeah, that’s a really great perspective.

Gerry Griffin: Yeah.

Host: Well, you were about 20 years here before you left NASA. How did you see it all change in that time?

Gerry Griffin: Actually, the only change that I really noticed is when I was director here, the then Administrator and his Deputy wanted me to be the guy that broke up the space station in the work packages so all the centers could be involved. And we were flying shuttles pretty fast at that point, but I had to do that. I felt like Henry Kissinger, which he was Secretary of State and they used to call it his shuttle diplomacy, his airplanes all over the world, flying to Rome and Vienna and wherever you had to go. Well, that’s what I felt like, except it was in a Gulfstream I, which is a very slow prop-driven airplane. But I went all over the center and I tried to convince, at that point I said, you ought to give the station to a single lead center, and if you don’t want it to be JSC, if you want to break up the Yankees kind of story, then give it to Marshall, give it to Kennedy.

I even went and talked to Don Hearth, who was the then Center Director at Langley. I said, “Would you be interested in running this thing if I could talk Beggs and Mark into it?” And he said, “No way.” Said, “I don’t want, I don’t want a piece of it. I want to stay in the research business.” And, so I said, “Okay.” But I was, and finally I started breaking it up into small pieces. And it was kind of like it was a little bit like the workforce development job, instead of getting it done more efficiently and build it on trust. So anyway, it, that’s what I noticed more than anything is how we had become a little bit, you’ve got to kind of even out the playing field, it’s kind of like giving a trophy to everybody that plays the game, whether they win or lose.

And the other centers, as I said earlier, were outstanding. They were really good, but they weren’t necessarily ops people. You know, or they weren’t necessarily strong in this or that or the other. And the three centers between Marshall and JSC and Kennedy, we had the talent to do it, I think. And our contractors, of course, they were critical. But in fact, you know, we didn’t cut a lot of hardware in Johnson Space Center that flew tools and things like that. So yeah. I really do think the for the long run, NASA has slowly crept into that too many decisions at too high a level which are time consuming, and they’re very costly and straining for budget. I believe if I were king for a day, I’m not saying it’s easy. I believe I’d put more responsibility down at the centers and see if we could crank it up a little.

Host: And since you left NASA, you’ve been pretty busy.

Gerry Griffin: You’ve been really busy at NASA, and the ISS, you know, has been marvelous machine, but my goodness, it never goes away. It doesn’t land.

Host: I know, I know.

[Laughs]

Gerry Griffin: So the people land and some of the cargo lands. But, man, I can’t imagine those hours of managing the control of the space station. It’s got to be tough.

Host: It’s constant. It’s admirable. But you’ve been pretty busy too since you left NASA. Some of those things. You are a technical advisor on some blockbuster films. We’re thinking “Apollo 13,” obviously, “Apollo 18,” “Contact,” “Deep Impact,” “Fly Me to the Moon,” is a new one.

Gerry Griffin: Is brand new.

Host: You acted some of those. Tell me all about it.

Gerry Griffin: Well, I was part of a group of people that met with Ron Howard. I was already living in the Hill Country, but I got a call from his office saying, “Could you meet with him?” And we went to the old control center, the third floor before it was restored. And, I said, “Sure.” He’s trying to decide whether to make a movie out of it or not, out of Jim’s book, Jim Lovell’s book. Which had been located by the son who worked for Ron of a flight controller named Jerry Bostick. Michael grew up with my kids from about that age up, but he’s the one that found that, and he was working for Ron Howard. So anyway, we, I went, I came down here from the Hill Country and went to the control center. And here was Ron Howard, but here was also Tom Hanks and Kevin Bacon and Bill Paxton and the head of Universal Studios and the writer and others. And there was about six of us that had actually been involved in the mission. And he told us right away, he said, “I’ve read the transcript.” And I’m sure he hadn’t read all of it, but he read enough, he said, sounds like a normal mission. We all kind of looked at, well, not quite. But he said, “But weren’t you scared?” He said he was trying to find the emotion in it.

Host: Right, right.

Gerry Griffin: And we all kind of looked sideways. No, that’s not the right word. We were concerned, but we were, this is what we were trained to do, you know, so you just get to it. And we did four hours there and then did four hours at the barbecue place outside of, we did four more hours of talk and questions. And boy, they had done their homework. Tom Hanks had really done his homework, and they asked us a lot of technical stuff, but finally when they left, which was about six o’clock at night after starting in the morning, I didn’t think he would be making the movie. Cause we kept telling him, we were just working options. And that’s the way we did things.

Host: It wasn’t dramatic enough for him.

Gerry Griffin: So we went away and about 30 days later, I get a call and said, “Would you like to be a technical advisor for the movie?” And I said, yeah, I didn’t know what I was getting. I gave away about three or four months of my life. And when we got out there, I remember the first time Jerry Bostick was also a technical advisor. He was a flight dynamics guy and father of the guy that found the material, too. So, if Ron said it once, and particularly when we started shooting, finally, it took us a few days to kind of get cranked up. And he said, “Remember, I’m not making a documentary. I’m making an entertaining movie. I want it technically to look right. And in the technical stuff to sound right, but I’ve got to have license to do this or that or the other.” Well, he would do something, you know, they would, we’d what do you think he’d, you know, he’d ask all of us, what do you think? Well, I said, well, that’s not quite right. And he said, “Gerry, I told you I’m not making a documentary.” Well, he asked. And, I said, okay. It took a while for the creative side of my brain to start kicking in. And, so it was, and then he had to, if you look at Apollo 13, anytime there’s a control center shot where it’s aimed at the big boards right on the front. There are people walking this way and they walk this way and they, there’s just constant motion, people walking back and forth. And I said, that looks chaotic. I said, that’s not the way it was. And we didn’t have a bunch of people tracing. They actually had extras set up where they could go one way and then they’d send them back the other way or new people this way. And it was, anyway, he said, you don’t have what he, something like I’m paraphrasing. You don’t have many shots where there’s no motion except maybe in a love scene. And, so I said, okay, I get it. It didn’t hurt the technical piece of it. It was just not like it was.

So that took getting used to, and then the other thing I found out is how much script, with the writer’s consent, that I had to rewrite because I tried to tell him the air to ground conversation was more of a disciplined conversation, it was a conversation with discipline. It wasn’t stilted over and out kind of discussions, you know, and a few times you might get a little more serious, but quite often he’d say, “Hey, Ron, do this,” or, “Hey Fred, have it. Turn the switch over there or something.” So it was done with the discipline, but it was not stilted stuff. And he was amenable to changing all that. And so they, I, rewrote a lot of that. In fact, I’ve worked five feature films and I’ve done script on all of them. Which kind of fun. And I’ve turned down a couple of ones I didn’t like, I didn’t even work at them. But, anyhow, it was a fun business. It’s different, I had a jaded thought about Hollywood. I thought it was mostly glitz. But you know what? I found out on 13 and it was same. And the other people were dedicated, hardworking in at 7 in the morning sometime not get out till 10 at night, back at 7 in the morning, actors having to go through makeup again and all that. They worked hard. And they were working toward a common goal. Which reminded me very much of what I had done in Apollo. They believed in their mission, too. And so it kind of changed my view of Hollywood.

Then “Contact” came along, and I got the opportunity to work with Jodie Foster, is amazing. And wrote a lot of script there. And that’s the first time I got in front of the camera, and they had to do what they call a Taft-Hartley force to get me in, because I was not a member of SAG.

Host: Right. But you are now.

Gerry Griffin: I am now. But they could force me in once without me joining. So we finished that. That was a great movie. I really enjoyed that one. Got to meet Carl Sagan before he died while we were shooting. But met some very interesting people on that one. But Jodie was the one that really impressed me. And then I went to “Deep Impact” with Bobby Duvall, that’s what we call him. And Robert Duvall, that was an experience. And he was neat. I went back to his horse farm in Virginia and spent a weekend with him going through the script. And he didn’t live in Hollywood, he said he couldn’t stand it out there. But he was a fun guy to work with. And it was a very interesting movie. And then did “Apollo 18.” We shot that in Canada, in Vancouver.

Host: Oh, I didn’t know that.

Gerry Griffin: Yeah. And that was a Weinstein movie. And I never met Harvey. I met his brother. And it was different. It was, for one thing, it was colder than heck. It was really cold up there and everybody and coached cause we were in this warehouse where they put this lunar surface set in and no heat in wintertime cold.

Host: It’s cold like the Moon.

Gerry Griffin: Yeah. And then came my last one, oh, it was in “Contact” where I got in to the first acting rule, “Deep Impact,” I did the same thing. And again, I was typecast. I was in a control center, but they couldn’t force me into that one. The director wanted to put me in it, and so I had to join SAG and they paid for it. Nice thing about that is when I got home after we finished “Deep Impact,” month or so later, I get this check in the mail, residual check from “Contact,” nice check. And I still get them, I still get them and I get them from “Deep Impact.” And I will get them from “Fly Me to the Moon.” So go buy those DVDs and Netflix, anything you can think of buy it all.

Host: You got it. Anything for you Gerry.

[Laughs]

Gerry Griffin: But I haven’t gotten that first check yet. And it was interesting, this last one, “Fly Me to the Moon.” It’s everything except Apollo 13, strictly fiction. I finally got the creative side of my brain, exercised enough that I understand what they’re doing now. And that made it a little easier working with this director, a guy named Greg Berlanti. And then Scarlett Johansson and Channing Tatum, and Ray Romano, and Woody Harrelson was really fun. It was probably one of the, it was one of the fun things, probably one of the most enjoyable. Laughed a lot. It’s a romantic comedy. With a nice twist at the end. And I’m not going to tell you anymore if you haven’t seen it.

Host: Good. I think it’s my weekend plan now.

Gerry Griffin: And she is so good. And so is Channing, both of them. And both of them took the opportunity to come up to me while we were in production. And when I met Scarlett the first time, I said, “It is an honor to meet you.” I said, “I’ve actually seen your Marvel stuff,” that she does. I said, actually, I’d gone back and looked at it after I knew I was going to meet her, but that’s smart. But I said, an honor to meet you. And she looked me square in the eye and she said, “No, it’s my honor, that’s because you really did this.” And I thought, how nice of her to say. And Channing came up to me, and in one scene we had a camera move and took 20 minutes. And he came up to me during that time and just said, you know, sir, he had to call me sir. But after that he called me Gerry, but he said, sir, said, “I just want to tell you how proud I am of you.” And again, I thought how nice of him to say that. Nice people, nice people. That’s a fun movie. It turns out to be more like a Hallmark theater than it does hard stuff. And I know it is gotten some, well, I’ve been told, cause I don’t do social media anymore. That it’s gotten a lot of criticism because it had something to do with a fake landing. Watch it to the end, fella, you know? Anyway, that’s what I want to say. Watch the thing. This was before it was released. But anyway, the movie business has been a… it’s been a nice break because I’ve never stopped talking about real space stuff. And I’ve always felt an obligation, particularly to the American people, Europeans are crazy about Apollo. But I’ve always felt an obligation to tell the story that I do a lot for nothing. And then I do some things for a fee. I went to Australia and got paid nicely. But I really do it because I think those of us that are still around ought to talk about it and remind us where we were 50 years ago.

Host: Yeah. I’m really grateful you came here today to talk about it. I’ve got one more question for you though. So, looking forward, what do you hope we see in the future of human spaceflight? And what do you think are the most important lessons learned that we have to carry forward?

Gerry Griffin: I think the thing we’re going to have to do is recognize, I think the commercial, having the commercial people are a big asset. And as late was late in coming, I thought somebody would… one, I thought one of the big companies would start spending some of their own money, which I had tried to talk some of them into way back when I was director here, why don’t you invest some? And they basically said that our shareholders wouldn’t approve that, too risky. And I thought, well, that’s probably true, but my God, you’ve made a fortune off a risky business. But I think having two billionaires step up and at least jump starting the commercial piece, I think is a big asset for the future.

I believe the commercial sector will own the low Earth orbit domain. They will do the launching. They will do the recovery. They will and do some very, very important stuff. Some of them may want to go on. I know I’ve heard Musk say that he wants to go to Mars. Bezos been a little quieter about that. He’s building a great vehicle. But anyway, that leaves NASA to go deep. And to me, that’s what we ought to be doing. We ought to be going back to the Moon, onto Mars. And this is just Gerry Griffin opinion. I think, and it’s not global warming, but I think a thousand years from now, 5,000, 10,000, you name it, I don’t know where it is, we’re going to use up this planet. and I mean, we’re going to use up the resources and we’re going to have so many people on it. And we’re going to suck everything out it we can. And I think if the human species is to survive, we’re going to have to do it somewhere else.

So to me, the important thing for NASA and the country to think about in the world even is how do we move around in deep space? How do we travel out there? Getting to the Moon is tough enough, and that’s only, you know, 240,000 miles away max. And then to go to Mars is entirely different subject, much harder. And to go to even beyond that, and, you know, the scientists are looking for small planets that are either around another sun or around some object that we can get to. And if you few light years places that might be habitable, it might have an atmosphere that we could deal with, I think we ought to spend a certain portion of the national budget. And it’s like, right now, I think it’s a half of 1%, on learning how to move around in deep space, how to go places, how to land, how to stay in space, even for a long time. Because you’re going to have to do that occasionally, trying to figure out what you’re going to do next. Now, like I say, this is not coming up. I mean, it’s years in the future, but I really think we need to do that. And I think the Artemis is a start.

You know, Apollo is a small step in exploring space. I mean, we landed six times on a closest body to us, other than the Earth. Artemis will be a little bit bigger step, but it’s still a baby step. We need to learn how to go even further than that. So to me, it’s something that we need to do. And, you know, I look at the size of our budget, $25 billion, compared to, not the entitlement programs. You can’t do that, you got to get with, but DOD spills that much, you know, in a day or a year that we could double that. There’s got to be a resolve that, and it kind of goes back to something that George Low and I focused on back in 1972-73 period. And that is that we haven’t spent a dollar on the Moon. We haven’t spent a dollar on Mars. It’s all been spent here, learning, doing, getting to the Moon, getting to Mars with robots. Very fancy robots, good ones. And we need to do more. And we’ve got, I think ultimately, NASA needs multi-year funding.

Now, we’ve talked about that since ‘72, ‘73. Something like a five-year horizon, because every time they sawtooth us and they take us down, and then that causes a slip in the schedule. And then when we come in at the end, oh, well you’re overrunning, right? Well, no kidding. No kidding. We’ve got to cut back. We can’t take our standing army and say go home. We may be able to cut down a little bit, but when we go into one of these cuts, if you cut Artemis or you cut, I don’t care what it is, cut it, cut a robot to the lunar surface, you’re killing us. And you’re making your prophecy as you go, but you don’t ever own up to the fact that you caused it Congress or you caused it OMB or White House, whoever. So it’s going to be a tough battle. Artemis will be constantly hard fight. But it sounds like the agency is trying to do that, so that’s good.

Host: Yeah. I’m ready for that challenge. Thank you so much, Gerry. I’ve loved this conversation.

Gerry Griffin: Well, I’m glad you have, I enjoy talking about it.

Host: And I’m no movie star, but thank you, really not just for being here today and continuing to tell the NASA story, but for everything that you did during Apollo and putting a human on the Moon with us. I mean, the world would be so different without you, without your teammates. I can’t imagine.

Gerry Griffin: I think you’re right. I think what we did 50 years ago was amazing. When I look back at it, bunch of young people, good leaders, and, you know, Kennedy set the goal to do it within that decade. And we lost almost two years after the fire. And we lost another almost year, about a year, 10 months, I think after Apollo 13. But the system stayed with us that whole time. And that was so important. And we got on with it, but I think it takes a lot of work. And I know the people at Headquarters. I haven’t spoken to Bill Nelson in some time, but I have with Pam working hard, keep it going.

Host: Well, thank you for your service to the country, for your service to the agency, and for coming and being with us here today.

Gerry Griffin: All of that was my pleasure.

Host: Thank you.

[Music]

Host: Thanks for sticking around and I hope you enjoy getting to know a little bit more about Gerry Griffin. If you want to know what else is up with NASA, you can visit us online at nasa.gov for the latest. You can also continue your audio journey at nasa.gov/podcasts. Reach out to us here at Johnson Space Center on social media, whether that’s Facebook, X, or Instagram, and use #AskNASA on your favorite platform to submit your idea, making sure to mention it’s for Houston We Have a Podcast.

This episode was recorded Aug. 16, 2024. Thanks to Charles Clendaniel, Josh Valcarcel, Will Flato, Dane Turner, Abby Graf, Jaden Jennings, Gary Jordan, and Stephanie Castillo. And of course, thanks again to Gerry Griffin for taking the time to come on the show. Give us a rating and feedback on whatever platform you’re listening to us on and tell us what you think of our podcast. We’ll be back next week.

This is an Official NASA Podcast.