From Earth orbit to the Moon and Mars, explore the world of human spaceflight with NASA each week on the official podcast of the Johnson Space Center in Houston, Texas. Listen to in-depth conversations with the astronauts, scientists and engineers who make it possible.

On episode 318, Michael Lopez-Alegria, former NASA astronaut and current commander of Axiom Mission 3, discusses his career and the upcoming private astronaut mission to the International Space Station. This episode was recorded on October 31, 2023.

Transcript

Host: (Gary Jordan): Houston, we have a podcast! Welcome to the official podcast of the NASA Johnson Space Center, Episode 318, “Axiom Mission 3.” I’m Gary Jordan, I’ll be your host today. On this podcast, we bring in the experts, scientists, engineers, astronauts, all to let you know what’s going on in the world of human spaceflight and more. The International Space Station is open for business. In 2019, NASA initiated a directive to welcome businesses to explore commercial opportunities on the International Space Station. Why? Well, the International Space Station is not meant to be in low Earth orbit forever. So NASA’s current plan is to maintain human presence in low Earth orbit by using commercial companies to provide the rides, the destinations, the cargo shipments, and more. So to realize this future, the ISS being the test bed that it is, is being used to evolve how commercial human spaceflight missions work through an effort called private astronaut missions.

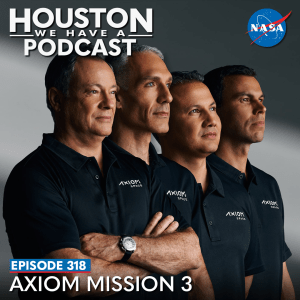

So already we’ve had a few private astronaut missions to the station, namely from Axiom Space. The missions were Axiom Mission 1 and Axiom Mission 2. We learned quite a bit just on two missions on how government and private companies can work together to accomplish their goals. And the more we do it, the more we learn. Now, the next private astronaut mission is Axiom Mission 3. This planned 14-day stay will see astronauts from all different countries, including the first Turkish astronaut, and is packed with research, outreach activities, and commercial activities. On the flight is Pilot Walter Villadei, representing Italy and the Italian Air Force. Mission Specialist, Alper Gezeravci of Turkey, and Marcus Wandt, ESA, or European Space Agency astronaut from Sweden. Commanding the mission is our guest for this podcast, Michael Lopez-Alegria, representing the U.S. and Spain. Mike is a former NASA astronaut and veteran of five space flights, including one private astronaut flight.

The Naval Aviator joined NASA as an astronaut in 1992 and flew on space shuttle for three short duration missions that span from 1995 to 2002 on three different orbiters, Columbia Discovery and Endeavour. He flew a long duration mission, Expedition 14, launching on a Soyuz from Baikonur, Kazakhstan, and spending seven months in space. He remains a record holder for number of spacewalks by a NASA astronaut at 10 in his career. After retiring from NASA, he served in a variety of roles and in both public and private capacities, advocating for commercial spaceflight and now serves as chief astronaut of Axiom Space. In 2022, he commanded Axiom Mission 1, the first private astronaut mission to the International Space Station. On this episode, we’ll learn a little more about Mike L.A., his passion for commercial spaceflight, and a bit more on the upcoming private astronaut mission to the International Space Station, Axiom Mission 3. Let’s get started.

[Music]

Host: Mike Lopez-Alegria, thank you so much for coming on Houston We Have a Podcast today.

Michael Lopez-Alegria: Good to be here.

Host: It’s about time we’ve had you on. Honestly, it’s my fault. Just a poor organization to get you on before Ax-1, and you’re super busy, but very glad we can make the time now because, you’re about to launch to the International Space Station as a private astronaut mission commander for the second time. Thinking about that, just sort of sitting in that moment of where your career started, your time as a NASA astronaut, and now as a private astronaut mission commander for the second time, how does that sort of sit with you?

Michael Lopez-Alegria: Sits great. Look, I think any astronaut that’s been to space wants to go back in general. I had written off that possibility when I left NASA just because I changed careers and I wasn’t thinking at all about any kind of a return. I was pretty happy with my 20 years here. You know, this opportunity just presented itself organically and of course, who could say no to that.

Host: It’s a wonderful thing and I think we’re going to be getting into it throughout this conversation, but for our listeners, for those who may not know, you are a very experienced NASA astronaut and your time and experience on preparing for this moment as commander of Ax-3 goes even farther back from that. I know you had an interest in flying. You were a naval aviator, and I wonder if there was something maybe early in your life, in your career, some mentor that sparked that decision to pursue an aviation route.

Michael Lopez-Alegria: Well, I’d like to say my mentors were the early NASA astronauts. So, you know, I grew up in the air of Apollo and was very touched by the first lunar landing. I remember how it unfolded vividly. And at that point decided I wanted to be an astronaut. Of course, I was 11 years old at the time, so I didn’t really stick with that dream. Through high school, things changed, but I ended up going to study at the Naval Academy, became a Navy pilot having studied engineering, and I wanted to figure out a way to combine engineering and aviation. That’s what test pilots do. So I started looking into becoming a test pilot, read an article in a magazine about the U.S. Naval test pilot school that had a sidebar that mentioned all of the astronauts who had gone to that institution. And they were all my childhood heroes, my mentors. So I was age 25 at the time. And that’s how the dream was reborn, I guess.

Host: Yeah. It seems like it never went away though, in a sense because maybe you were grounded a little bit more realism, like, “Ooh, astronaut just seems way too far out, but these things still interest me.” But you were saying that it was your heroes. It was other astronauts that had gone through similar experiences. So maybe it was somewhere in the background, maybe astronaut is a possibility. Was it still there or had it left you at that time?

Michael Lopez-Alegria: I mean, who knows what’s beneath the surface there as you’re growing up. But I didn’t think of it consciously. In fact, when I went to the academy, I thought I was going to be a submariner. And then I spent three days on a submarine, which changed my mind.

Host: You’re like, “Nope.”

[Laughs]

Michael Lopez-Alegria: Around that time, you know, the academy is on the East Coast. I lived on the West Coast, and so every chance I got when we were on break, I would catch what we call the military hop. So basically airplanes that were doing their missions flying back and forth, generally cargo airplanes. If they were, what they call “space available,” empty seats, you could sit on them for free. And so I got to hang around a lot of aviators and it was like, “These are my people.”

Host: Aha. That can seriously influence you one way or the other just the people that surround you. It’s the same reason I think people go into submarines. Right. Submarines are pretty tough, but if you’re surrounded by people that you enjoy being around, then it’s not so bad.

Michael Lopez-Alegria: Yeah, it’s definitely a different mentality. And I have friends who are submariners, so cast no aspersions in their direction. But, it wasn’t for me.

Host: Okay. Well, you found your calling and that calling led you to be welcomed by NASA as a NASA astronaut. That feeling must have been spectacular. You said the dream kind of came back and you ended up pursuing it. So I wonder why, what came around that, “Hey, maybe I should apply to become a NASA astronaut?”

Michael Lopez-Alegria: Well, I fell in love with this idea of going to test pilot school. And at the time, there was a subset of that program where they sent you to graduate school first. And I was lucky enough to be chosen for that. So I went to Monterey, studied aeronautical engineering, and then to test pilot school. And, you know, at that point it was all head full. I mean, I knew what my dream was. And I applied pretty early in my test pilot career, probably a little bit too early and did not make it. I came down to an interview, but it wasn’t my time. And then the next cycle, which was the 1992 class, I was selected. And you’re right, I mean, there are legends about getting that phone call from the chair of the selection board. But it is a life-changing day for sure.

Host: Yeah. So, you went through your training and you got chance to go into low Earth orbit. You got a couple of shuttle flies, you got to fly on three different shuttles. You got to go to the International Space Station. Quite a diverse experience. Your first one was an interesting one. You were doing microgravity experiments, but on the shuttle, not necessarily on the International Space Station. What was that one like? This is your first flight STS-73.

Michael Lopez-Alegria: Right. STS-73 in 1995 was a Spacelab mission. So we had a European-built module in the back of the shuttle’s cargo bay, and we got to and from the module through a tunnel that was connected to the middeck. We were a crew of seven. We had two payload specialists, you know, one each in Zeolite crystals, a guy named Al Sacco, and then another fluid physicist from Marshall named Fred Leslie. And then five NASA astronauts, four of us, sorry, three of the five. So total of five of the seven were rookies, which is interesting. And we were divided into two shifts so that we could work around the clock in this laboratory. And it was all about science. U.S. Microgravity Laboratory-2 was a payload. So three of us on the mission were pilots. I was a blue shift commander. The other two guys were on the red shift. Ken Bowersox was a commander, and he is now the associate administrator. Interesting story about Ken that we may get to a little bit later. But they let some of us pilots do what we called pilot science, but the real stuff was going on mostly in the Spacelab module with the experts. The other two mission specialists are both scientists. So it was a pretty scientifically oriented mission.

Host: This is your first one, and you had a variety of experiences up there. Your third mission was Expedition 14. You got to have a long-duration mission. And I wonder about the differences there, but this first one, we talked to astronauts who describe the short duration versus long duration as sprint versus marathon. And you’ve experienced both. I wonder how it compares to private astronaut missions as well. Because the private astronaut mission, Ax-1 was just a couple of weeks, Spacelab is short duration. I wonder if you have that same mentality, sprint versus marathon.

Michael Lopez-Alegria: That is definitely a thing. It’s very much based on duration. So whether it’s a PAM (private astronaut mission) or a regular NASA mission, I think short-duration missions are very much sprints. What’s different is a short-duration mission on the ISS, I would say is not as choreographed as a shuttle mission was, meaning we reviewed what we called the flight plan or the timeline in a shuttle mission. It was laid out in five-minute increments for the entire mission. So you knew what you were doing on flight day 11 at 3:25 in the afternoon. Expedition missions, and even short missions on the ISS, you might know what your payload complement is, but you really don’t necessarily know the sequence. So it’s a little bit different, but it’s a sprint in that you generally don’t get any days off or maybe half a day, you know, you’re working. The weekends aren’t weekends, they’re workdays. And it’s over before you know it.

Host: That is true. It goes by really fast. I wonder if the training, there’s some parallels there? Perhaps with private astronaut missions and the short-duration sprints. I mean, are you training for just this specific period of time and it kind of goes down to those five-minute increments? Or is it more like what we see now at the private astronaut mission, which is the general training, especially on the International Space Station that we see here in Houston, just here’s how things work.

Michael Lopez-Alegria: I would say certainly in the shuttle, we did a lot of simulations of asset and entry and rendezvous and undocking. For a station mission, obviously you do that stuff in your launch vehicle, whether it’s a Soyuz or a crew Dragon. But the actual sort of meat of the mission, the experiments, the day-to-day stuff, you rarely would take a chunk of the timeline and actually practice that. You would do activities that represent those kinds of things. We call them routine ops, or sometimes you’ll hear day-in-the-life sims. But that is just a representative timeline. If you’re lucky, you’ll have some payloads that will be on your mission. But generally, that’s not the case because especially on a private astronaut mission, we are really racing to get all of the payloads integrated, which for us kind of means that the procedures identified. So you don’t have a lot of the operations products that you will have on orbit, um, much before the launch itself. So you don’t have the luxury of practicing and experiment with the real procedure let alone the real hardware in a simulation.

Host: Okay. A little bit of differences there. I see. Okay. So, going to your next mission, STS-92 and 113 actually, I think these were ISS assembly missions. You still to this day, are among the top NASA astronauts for a number of spacewalks. And a lot of them were on these couple of flights. They were space station assembly missions. And so you got to put on pieces of the International Space Station, and several times, right now your record stands at 10, you got to go outside and take part in building this orbiting laboratory that stands today. I wonder when you reflect on that experience, and not just the spacewalking experience, but contributing to the construction of this national lab, which we’re still using for things that we may not even thought about whenever we were constructing during the ISS assembly phase, I wonder how now, 2023, you reflect on that time spacewalking.

Michael Lopez-Alegria: I don’t know if you’ve built or remodeled a house, but if you’re involved in the very beginning, let’s say you’re remodeling a house and you’re involved in the demo and sort of really putting the frame back together and that kind of thing. And then you live in the house for many years, or you go back to it afterward, and it’s almost hard to imagine what it was like at the very, very beginning. So STS-92, also called ISS Mission 3A, it was the third American assembly flight. So when we went there, there was nobody living on board. There were actually three modules up there. We brought two pieces, the Z1 truss and the pressurized mating adapter number three. And we did four EVAs back-to-back, two teams of two. And when we left the ISS, it was the last time anybody closed a hatch on an uninhabited International Space Station.

So either I think maybe while we were still in flight or not long after Bill Shepherd and the crew of Expedition 1 launched, of course, it’s been inhabited ever since. So it’s a privilege. And the EVA piece of it, I mean, as magnificent as spaceflight is, you can’t even imagine what a spacewalk is like. It really is the special of the special.

Host: Yeah. Just the perspective of looking down and just having that view. We talk about it constantly and I try to imagine it, but it’s just really tough. So you’ve seen the history of ISS. You’ve seen it’s in its infancy uninhabited, closing the doors without people in it. Now with continuous habitation, like you said, since 2000, you kind of in a sense refer to the International Space Station as the house that you were remodeling or building, and you just look back and be like, “Wow, I can’t believe how much progress.” Is that kind of how it was the last time you visited for Ax-1?

Michael Lopez-Alegria: Yeah, and it has changed. So the second to last time I was there was 15 years ago, or 15 years before the last one. A lot had changed it probably more than double in size, more than double the crew size. A lot of stuff like there is wires and laptops and cables and hoses and bungees. It’s really quite chaotic up there. And that’s very different. You know, Expedition 14 was definitely different. But even before that on the third mission, which was STS-113, we brought up Expedition 6 and brought home Expedition 5. And even back then, of course, as small as a station was, it hadn’t had time to accumulate all this stuff that’s up there now.

Host: Yeah, lots of stuff. There’s a lot going on, I suppose. And that comes with lots of stuff. Um, and certainly one of the things that I think we learn from as we’re thinking about low Earth orbit operations, how to make sure that we are continuing that progress along the way. Your Expedition 14 experience was your long-duration one. We talked about sprint versus marathon, but that Expedition is what you see. Some of the folks you got to spend time with on the station for Ax-1 were in the middle of this. And so I think you had an understanding of what that was like from a marathon perspective, from the perspective of spending so much time. I wonder maybe how that has evolved over time. You’re thinking about your Expedition 14 experience to maybe what you’re seeing with some of the Expedition crew members today on Ax-1.

Michael Lopez-Alegria: Yeah. I’ll go back to the house analogy. So this is like going back to the house you grew up in and your parents remodeled it a little bit since you left, but it still seems very familiar. So that’s what it was like to float into the ISS in April of 2022 after having been gone for 15 years. It felt familiar at once, but there were definitely some new twists. All of the stuff forward to the lab was not there when I was there before. And I could definitely relate to the experience of the Expedition crew having had a shuttle crew come during Expedition 14 and spend a week or so docked, and they did all the work.. So, you know, you are having guests in your house, and what do they say about guests? It’s like fish, you know, it’s after about three days, it’s time to get rid of ‘em. We tried very hard not to be that way with the Crew-3 crew who was led by Tom Marshburn. But it’s inevitable. I mean, we’re in their space and they’re used to having X cubic meters per person, and all X just got divided by, you know, a bigger number. It was very different, but they were super gracious and very helpful.

And, you know, the Ax-1 crew came from a very diverse non-astronaut kind of background. And I think, you know, as we get more into, I guess we’ll talk about Ax-2 and AX-3 and how the crew compliment has changed a little bit more toward the government astronauts who have a little bit more preparation in organic to their lives. But because of that, we did rely quite a bit on that crew to help us get through the timeline. We also were very ambitious in what we were trying to accomplish, probably too much so. I think we learned that lesson. So as these things are meant to be, you learn from them, and the next one’s better than the first and the third one will be better than the second, and it’ll keep going in that direction until we get to that perfect mission.

Host: Yeah. It’s interesting hearing your perspective and just the thought and the understanding of your experience as an Expedition Crew member, translates to something so relatable, just being a good guest, understanding what it’s like to have someone in your home as an Expedition crew member, what it’s like for a short duration crew member. A very interesting perspective. My next set of questions are going to lead us out of your NASA experience, but I remember something about you talking about a Ken Bowersox story, I want to make sure we get to that.

Michael Lopez-Alegria: What’s funny is as I feel like we’re going to transition from NASA into the next phase of my life, Ken Bowersox had a lot to do with that. So he was working for SpaceX at the time, and he and another former colleague who was also at SpaceX, a guy named Garret Reisman, I was out there doing something with NASA and we went to lunch, and they really were pushing hard for me to go work for this outfit called the Commercial Spaceflight Federation. And, it’s ironic now that, you know, Ken is in the position he’s in, and I’ve left CSF, but we’re still sort of dancing around the same pole a little bit. And, I respect Ken a lot. So I followed his advice, and it was really a very, very challenging time going to Washington as part of an advocacy group, knowing nothing about how Washington worked, knowing nobody there, having had no experience walking the halls of Congress. I mean, it was a lot. I would say it’s very different from learning how to be an astronaut because astronauts are trained very well. They train us to do everything you can imagine. A lot of things you can imagine. Whereas there’s absolutely no playbook for what I was doing here. And that made it hard. But it was very rewarding.

I got that inspiration during Expedition 14, as we were preparing to launch with my cosmonaut crew mate, Misha Tyurin, the third person was going to be a spaceflight participant. And it was sort of the fourth, I want to say the fourth one of those missions that were brokered by space adventures. I wasn’t too thrilled with the idea, to be honest. I felt like ISS is still in our construction, you know, these people don’t even know how to wear a hard hat, you know, same kind of we versus they, which I unfortunately can understand that mentality. A couple things changed.

One of them was that the third person had a medical problem, was not able to fly. So their backup flew and their backup was a woman named Anousheh Ansari. She’s an Iranian born American businesswoman. I mean, first of all, she was great in training, and she was very professional when we were on board in her tasks. But what really got my attention was she was blogging from space, blogging in 2006 was a brand-new thing. And literally a million people on Earth were following what was going on in low Earth orbit. And this is a million people who would not have otherwise cared at all about space, human spaceflight. And that really kind of flipped a bit in my head about this experience of human spaceflight. You know, at that time, probably 400, maybe 450 people had ever been to low Earth orbit, and yet she was reaching a million people at a time. While we go back to schools and things like that as professional NASA astronauts, I think this idea of a platform, like a blog—we weren’t reaching, reaching a million people, let’s put it that way. So this idea of democratizing the experience to let other people, then, those with the right stuff, let’s say, really resonated with me. And so when I started thinking about leaving NASA, that’s where this whole conversation started with the CSF. And Ken and Garrett really helped me take that leap.

Host: So to expand on that CSF, right. Your role really was taking this experience from Expedition 14, understanding this mentality of democratizing space and connecting with people, connecting with organizations, connecting with influencers, legislators, to really give this narrative some legs. Am I characterizing your responsibility correctly, or was there more to your role than maybe I’m missing?

Michael Lopez-Alegria: You got part of it right. So we’re an advocacy group representing commercial space companies, and back in the day it was some of the same names as today, Virgin Galactic, Blue Origin, SpaceX, a couple that aren’t around anymore. But the idea is that this idea of commercializing space, and we have to be careful because space has been commercial for a long time. I mean, NASA uses contractors to build systems that it owned, like Mercury, Gemini, Apollo, Space Shuttle, et cetera. But with the beginning of commercial cargo, and then commercial crew, rather than NASA hiring these companies as basically labor, where NASA made all the decisions, kept all the IP, and had all the responsibilities. They said, “Look, we’re going to give you some very little high-level requirements. You guys meet these requirements, and we’ll buy this service from you. You keep the IP, if you want to use it for something else, you’re welcome to. And oh, by the way, we’ll throw in some development money at you.” And that really was what we were fighting for. At that time, commercial crew was very much teetering on extinction.

Host: Oh.

Michael Lopez-Alegria: And so we fought hard to get NASA’s budget increased for the commercial crew program, in addition to having to fund SLS and Orion, which were sort of the gorillas in the room at the time. So is that right, gorillas in the room? Or do I want to say elephants in the room? Anyway, the 800-pound gorilla, I think I was mixing two metaphors.

Host: Oh, yeah, yeah, yeah.

Michael Lopez-Alegria: Anyway, it worked, you know, we got increases in the budget. And around that time, SpaceX had its first successful commercial cargo launch and, you know, CCT cap came, CCI cap and CCT cap, and all those things were happening at the time. So it was a pivotal time to be involved. And I think having, you know, what they call on the Hill a “blue suitor,” or somebody with NASA heritage or pedigree was helpful because I think a lot of people in that commercial space world at the beginning were thought of as fringe kind of tinfoil hat weirdos and I was trying to bring some legitimacy to the organization and grow the organization. I’m happy to say now they’re an absolutely sought after and valid voice in some of these conversations with congressional offices and also with executive branch of the government.

Host: Thanks in part to the groundwork that’s been laid over time of just marrying this private idea, what may have seen a little lucrative at the time to something that is reasonable and in practice, and which we’ll talk about here coming up soon. You have this advocacy for commercial spaceflight, and I wonder from there how it led you to Axiom Space?

Michael Lopez-Alegria: So I worked for CSF for about three years, and when I left, as I say, hung up a shingle. So I started doing the same kind of work, but as a consultant. Really wanting to rely on my operations experience for commercial space companies. Turns out the work that I had done on the Hill and other places is what people were really interested in, which I still found somewhat distasteful, but necessary until Axiom came along. So I’ve known Mike Suffredini for a long time, and in 2016, he formed this company with the idea of building a commercial space station. And I thought finally something I know something about, right? It’s not about budgets or, you know, and how many jobs in your district. It’s operations. And so I became a contractor for them. The company, I think I was like number four. I would’ve been number four as if I were an employee. So we were in an office not far from here. And we’d get together. I was still living in Washington, but commuting here pretty often. And it just started very, very small and really took off. And now the dream for having a commercial space station, I think will soon become a reality. And we’ve expanded into these private astronaut missions. We’re at the beginning, were not contemplated, and neither was the work that we’re doing on the next Artemis spacesuit. So it’s a pretty exciting time.

Host: As we’re laying the foundation here for what’s to come with the idea of how we take those first steps to that future. One of those first steps that’s part of this is this idea of private astronaut missions. I think of it as a small step because the government is very much a part of it, with NASA enabling this ISS to be a place to try this out. Space tourism, something that’s been talked about for a long time, and at least on the NASA side, has not been commonplace up until now. So I wonder, you know, you had this experience on Expedition 14, and then you had the chance to be your number four at Axiom Space. This company in its infancy, trying to come up with ideas on how to make this work. I wonder where from there the progress was made to say, “Hey, let’s advocate for maybe using the space station as a place to take that first step towards what we’re envisioning.”

Michael Lopez-Alegria: Well, it all starts with the commercial space station idea. So that’s what the company was founded on. He and Dr. Kam Ghaffarian and the other co-founder got together and they, you know, sat around for a while thinking, is this thing possible to do? And can you make a business out of it? And they decided that they could. And so that was the objective, was to build a commercial space station. We were awarded a contract by NASA in the beginning of 2020 that allowed us to attach a module to the ISS. And then from that, the idea said, “Well, it would be great if we could have some experience on how to manage missions with that module, and then subsequent modules that we could attach to it.” And ultimately, we plan to separate the module from the ISS when the ladder is decommission.

But it’s better to have the experience from an operation standpoint, both in terms of your team that you develop to run the mission, as well as the interfaces with NASA. Because ultimately, we’d like NASA to be one of many customers. And so we want to give NASA confidence that we know what we’re doing, so that when the time comes and they’re looking around for a place to go and lower Earth orbit, they’re very familiar with us. So the whole idea of private astronaut missions is to establish that operational experience, and at the same time, the relationship with NASA, and also to build a market. Because, as I said, we want other customers beside NASA or the space agencies. And so you start looking around and there are private people, individuals that may want to fly. There are companies, there are research institutions. There are countries that don’t belong to the ISS partnership. So these are the people that we’re trying to cultivate as our customers for these private astronaut missions. And hopefully that’ll continue even after the ISS is gone.

Host: And we’ll lead into that customer base too cause you mentioned this a little earlier, right? Ax-1 and the evolution of the customer base as we get through some of the later Axiom Space missions. I wonder though, you were the first private astronaut mission commander, and I think at that time, were you the chief astronaut?

Michael Lopez-Alegria: I don’t think we had the title.

Host: Okay. Didn’t have the title. So when Axiom Space was thinking about what is needed for a private astronaut to know, what is the role of the commander, when you were approaching your job as commander and thinking about the foundation of what is it going to take to be a successful private crew, how did you approach some of the first baby steps of getting together this first cadre?

Michael Lopez-Alegria: Well, dirty little secret at the beginning, we did not necessarily plan to have an Axiom commander. So it would be better for the company if we could sell all four seats instead of only three of the four seats. And as we started looking at the potential clients, they were not too keen on going without somebody that had not had experience. And NASA turns out, felt the same way. And so when we looked around the room at Axiom about who had experience, you know, I was the guy that raised their hands.

Host: All heads turned to you.

[Laughs]

Michael Lopez-Alegria: Yeah. And so at that point, it becomes, you just fall back on the training that I got at NASA. Now, obviously, there are a lot of differences in leading, a NASA crew and leading a private astronaut crew, but there are a lot of similarities as well. So, you know, the first thing you worry about is training. Luckily, NASA had put together a syllabus whose name escapes me right now, but it was a visiting crew member, syllabus, something basically tailored for private astronauts. It turns out it wasn’t perfect and it was another lesson that we learned on Ax-1 that there were some courses we probably didn’t need, and there were probably some other things that we could have spent more time on. But the training is the biggest piece, and of course that has to do with ISS, you have to go through the same training on your launch vehicle, which for us was a crew Dragon. SpaceX took care of that quite well. We did a zero g training, we did a centrifuge, we did obviously some payload training. We visited Marshall. We did a trip to Alaska under the auspices of the National Outdoor Leadership School, kind of taking a page from the NASA playbook where they send crews out to go suffer together and bond. And we did that and we did suffer, and we did bond as a result. So a lot of the sort of the profile of the mission training was very much like a NASA mission, but obviously the team did not necessarily have the same level of preparatory training for it.

Host: Yeah. You were thinking about that because let’s take a look at Ax-1 here for a minute and look at the compliment. We have Larry Connor, Mark Pathy, Eytan Stibbe. It was a unique crew. You mentioned this in the beginning, you know, how do you teach people who have never been to space before how space works? You of course, were the person that had been to space. As you went through that process and got this crew together, what were some of the ways that, ultimately you decided, “Okay, here’s what a private astronaut needs to know.” What were some of the observations on that first mission that made it successful? And then also in a sense, you’d mentioned lessons learned, that we learned and are going to apply for the future.

Michael Lopez-Alegria: I think I was most of all surprised at the level of their competence based on their backgrounds. Now, let me say, Eytan was a fighter pilot in the Israeli Defense Force. So he was very well steeped in operations. Um, Larry was a champion acrobatic pilot. Also had some time and a pretty successful career as a non-professional race car driver. So a lot of this kind of adventure, again, operations, you know, using machines and that kind of thing. Mark was the outlier. He had none of that kind of background. But he was, I think, just naturally adept at that sort of thing. And so they really picked up on astronauts, I would say pretty quickly. I noticed, you know, perhaps some of that is due to background, but a lot of it is due to their own drive, their initiative.

Host: They really wanted this. Yeah.

Michael Lopez-Alegria: And I noticed that first on our NOLS trip, the first training that we did together. And I mean, these guys are all extraordinarily wealthy people. They are used to having things brought to them in the manner in which they’ve asked for them, at the time at which they asked for them, et cetera. And there is nothing like that in NOLS. I mean, it’s tough. Back country hiking. We went to the Talkeetna Range in Alaska. It rained, it snowed, it sleeted, it was miserable for a good week. And they didn’t complain. It was really, “Hey, we’re going to get through this.” They all showed up. That was the first indication to me that we are going to be okay.

Host: Awesome. Suffering and bonding. Very good. So you think about this crew complement, not just the crew complement, but the mission Ax-1. This was a mission of science. There was a mission of outreach. There was some commercial aspects to it, looking at Ax-1 and how the first private astronaut mission was designed, where were those focus areas? And then again, in the same sort of theme here is where were those focus areas? What was good and what are some of the lessons learned?

Michael Lopez-Alegria: You know, those topics that you mentioned, except for the commercial activity stuff looks just like a NASA mission. I mean, science and outreach. What we didn’t have to do is maintain or operate the space station. So especially in Expedition 14, was a big chunk of what we did. I think it’s less now because there’s more people, you know, to do the same task. So each person has to do less of that per day. But other than that, it looked very much like that. And these guys brought their own science, which is also different from a NASA mission, where you as an astronaut are handed a payload complement and taught how to operate the experiments, whereas they got to choose their experiments. So Larry teamed up with the Mayo Clinic and the Cleveland Clinic. Eytan through the Ramon Foundation, and you probably know that story, but Elon Ramon was tragically killed on the Columbia accident. Eytan was instrumental in helping his family set up the Ramon Foundation afterward. And then Eytan used the Ramon Foundation to go out to with a nationwide call for both science experiments, but also outreach opportunities. And then Mark teamed up with the Montreal Children’s Hospital and the Royal Canadian Geographical Society, and also through CSA, the Canadian Space Agency, which interestingly adopted him as a member of their astronaut corps, which I thought was really nice.

Host: Oh, that’s news to me. Very cool.

Michael Lopez-Alegria: So anyway, they brought their complement of things. Now we didn’t get to fly everything that they wanted to fly, but we probably flew too much. In other words, they’re a paying client, you want to make them happy, they’re ambitious, we can do this. And, you know, we have a lot of ops, NASA ops experience on our team and who were saying, “This is a little heavy. You sure you want to try all this?” Oh, yeah, yeah. We got it. And we probably should have been a little firmer in our guidance, but heck, we loaded up the plate and turns out we couldn’t eat it all. We actually ended up eating all of it, only because our mission was extended. Our landing was delayed. It’s supposed to be eight days aboard and ended up being 15 days aboard. So we almost spent twice as much time as we were supposed to. So we did get it all done, but it was a big lesson that we learned. Also, we probably had my timeline a little more folded. It needed to be doing, you know, Axiom specific stuff, as sort of just another crew member. And as a result, when Mark or Larry or Eytan had an issue, I was pretty busy, and they would have to go to the NASA crew for help. And that probably wasn’t ideal. So on Ax-2, Peggy Whitson, the commander’s, timeline was drastically reduced. So she had a lot more free time to help with them. And we’re repeating that on Ax-3.

Host: It worked well for Ax-2. Yeah.

Michael Lopez-Alegria: Yes, it did. And I think the improvement was noted by everybody.

Host: Excellent. Leading right into that Ax-2, right. There were a couple of changes. You didn’t get to completely pull away for Ax-2, right? You were backup commander and you were still along the training flow. This one brought in Saudi astronauts. It was a different complement. You mentioned a couple of adjustments from the lessons learned from private astronaut missions. We established this right up front is let’s figure out how to do this. And of course, with that comes lessons and refining. So in addition to reducing the time commitments of the private astronaut mission commander, what other changes did we see for Ax-2?

Michael Lopez-Alegria: Well, as you mentioned, the crew complement was quite a bit different. So instead of three private, when I say private astronaut, I mean privately self-funded. We had one private astronaut, and then two government astronauts, which were both Saudis. That was different in that the astronauts were not the customers. Their government was a customer. And it seems like a subtle nuance, but it’s actually a pretty big change when it comes to things like the experimentation that’s done on board, the catering to the customer. As a customer service organization, we want to make our customer happy, which on Ax-1 was pretty cut and dried. The customer was the astronaut, but here it was a little bit different. Now how that impacted the mission, I would say the Saudis who were going to be the first woman and second man from Saudi Arabia to fly in space, big responsibility, a lot of emphasis on outreach. A very different weight put on them, I would say, than the private astronauts, a little bit like a NASA astronaut. You know, you have this experiment to do, and you feel a real obligation to do your best at it. If you’re a private astronaut, something’s not going well. You say, “Well, I gave my best shot.” It’s a little bit different.

I will say the Ax-1 guys were very conscientious about trying to get everything done and doing it well. But it’s just a different mindset, I think, when they go into it. Other than that, you know, the timeline changes were probably the most significant thing on the training side, we did eliminate some things from the NASA training that were not probably anything that they would ever let us touch on orbit. I have a couple humorous examples. And then we spent a lot more time with what we call the ops products. So the things that we used to manage our time and space, the procedures, the timeline viewer, the stowage and transfer tools, that kind of thing. I would say that Ax-2 crew were much better prepared to use those than we were on Ax-1.

Host: Yeah. So John Shoffner was the private astronaut. You had Ray (Barnawi) and Ali (Alqarni) from Saudi Arabia, learning and refining these things. That was just one step of an improvement to making private astronauts that much better. Now let’s take that and jump to Ax-3. Ax-3 is a complement of astronauts representing more nations than I think any other private astronaut mission or even Dragon mission than before. Because you have two flags. We’ve got Italy, Turkey, as well as Sweden. Interesting group of professionals and private astronauts. Take us through the Ax-3 crew. Who can we expect to see up on orbit with you?

Michael Lopez-Alegria: So you mentioned Italy. Walter Villadei is a pilot. He was also the backup pilot on Ax-2. So we’ve trained together a fair amount. He has a lot of experience, even though he hasn’t flown in space before, he did several years of training in Star City as a cosmonaut. So he is left seat qualified. So about as high a qualification as you can have in the Soyuz. And has been involved in space policy within the Italian Air Force for quite a long time.

Alper Gezeravci is an interesting aviator from Turkey. He is a colonel in the Turkish Air Force, but he had a broken service. So he started out his aviation career as an F-16 pilot. At some point, for personal reasons, he chose to make a transition to tankers to KC-135 tankers. That’s a very unusual move for any Air Force pilot. He did it for very noble reasons. He did that for a few years and then left the Air Force and was hired by Turkish Airlines, first as a first officer, and then as a captain. Then after the coup in 2016, he was asked to come back to the Air Force, which he did. And now he’s flying both airplanes, F-16’s and KC-135’s. So he has more flight hours than I do. He’s a very experienced guy. And Axiom helped Turkey select him and his backup, Tuva Atasever, who is a very bright young man who studied at the University of California in Irvine in optics. I really hope he can fly as a crew member one day, because he’s a very worthy guy.

And then the last person to join the crew was Marcus Wandt, also a military Aviator. This one from Sweden. He started out his life as a special ops guy in the Army and as an enlistee. Got out, went to finish his engineering degree and master’s degree, and then applied for the Swedish Air Force where he was selected as a fighter pilot. Then the country’s aircraft manufacturer, SAAB, was thinking about making a new model of its most advanced fighter, and for which they would need test pilots. So they sent him to the US Naval Test Pilot School, same place I went. He finished at the top of his class. I did not. So we have Alper with more hours than I do, and Mark as who’s a better test pilot than I am. And after that, he became the chief test pilot of SAAB, worked his way up to be that position. So it’s an amazingly qualified crew. I think I would hold them up to any NASA crew that I’ve been on, favorably. And I can tell you that the experience so far, training both at NASA and at SpaceX has borne that out.

From left to right, Ax-3 crew members are Michael López-Alegría, Axiom Space’s chief astronaut, Walter Villadei, an Italian Air Force colonel and pilot for the mission, Mission Specialist Alper Gezeravci from Türkiye, and ESA project astronaut Marcus Wandt. Credit: Axiom Space

Host: You talk so highly about your crew members. They’re from all over the world. You know, Mark is from ESA. We’re bringing in just so many interesting people through this avenue of private astronaut missions. I want to continue this conversation about evolution. Ax-1, right? We talked about this a little bit, was the research complement. Now, you mentioned briefly Ax-2 research is now coming from the governments. And I think we could see this way more for this mission as well. You have research representing Italy, Turkey, Sweden. Can we expect to see a lot of this for Ax-3?

Michael Lopez-Alegria: Yeah, definitely. Profile-wise, it looks the same. A lot of research and outreach. And of course, the outreach component for these nations is very important because part of the reason that they’re interested in flying a human to space is for the inspirational factor that it gives to their young people. Ultimately, it builds up their workforce, technically capable workforce.

One wrinkle that I didn’t mention when I was referring to Marcus is that, as you did, he is an ESA Reserve astronaut, or now an ESA astronaut. He was selected in this last class, but not as a career astronaut, as a reserve. And that was very important for Sweden to have somebody that was, you know, sort of off-the-shelf and a hot spare ready to go.

I think what we’re doing here is expanding access to the ISS to countries that are not members of the partnership, or at least not traditional members of the partnership. And so this is sort of opening the aperture toward this idea of democratizing the experience, first with private people, then with a mix, and now with all government astronauts. And there are a lot of countries out there, right? We hope all of them will be clients of Axiom Station someday. And I think this is going to be a marquee mission in terms of the science that’s conducted.

Another wrinkle with taking into account that Marcus is from ESA is that all of the payloads that he’s working on come from Sweden and to some degree from ESA itself. But they’re being developed by ESA rather than by NASA. So the other countries have to go through us and the US National Lab, which ends up being a flow restrictor in a way because of the short time between when we were named as a crew. Well, I shouldn’t say we were named, we were started training as a crew at the end of April, and our launch was going to be in November. That was a pretty short runway, and we wouldn’t have been able to fly a very big complement if we had to get all that through the payload integration process in NASA. And luckily, with Marcus, a third of those payloads are going through ESA, which is going in parallel and doesn’t slow us down so much.

Host: I feel like this is sort of alluding to perhaps the changes that we will continue to see in the future. Right? You’re referring to Axiom Station, private station. Each customer is going to have very interesting needs that might take us a little bit by surprise. We have one way of doing this, but maybe we have another country that wants to do things a little bit differently. And it starts that conversation of just, “Okay, well this, it’s a little bit different from what we’ve traditionally done in the past. We’re bringing on new people that might need new ways of doing this.” And so in a way, it kind of helps us to just take that next step towards maybe the inevitable, I don’t know if I’m jumping too far, but I feel like it might be happening anyway, just the little roadblocks and perhaps inefficiencies that we just need to work out to just make efficient for the future.

Michael Lopez-Alegria: Well, I think if we’re doing our jobs, we will be discovering things and that means that we’ll be learning things and having to make adjustments along the way. We’re very keen on trying to make the Axiom Station be as plug-and-play as possible for the reasons you suggest, and also as modular as possible so we could add to it relatively easily. We really think that there is a great potential for in-space manufacturing. And so if a country were to come to us or a company or an agency and say, “We want to work on how to make this thing in space, we probably don’t have that hardware on board yet because nobody else has done it.” So we want to be able to develop the hardware, and if it’s small enough, we can put it in one of the existing modules, or you can make a module dedicated to do just that. Only that particular task. And so that’s really important, as you say, to have the expansion capability and have as little kind of built in obsolescence as possible. And we’ve learned a lot. The ISS is an amazing machine, but it’s pretty old and it’s been designed, I mean, a long time ago do we really need 1553 bus architecture? Probably not. Ethernet is pretty safe and pretty reliable now. All of the giant components that are on the external truss of the ISS, thanks to miniaturization, we can put a lot of that stuff on the inside of the Axiom Station. So if a box fails, you don’t have to start an EVA, as much as I like to do EVA, to go replace it, you open a cabinet and you swap it out.

Host: Yeah. Those efficiencies are going to evolve over time with technology too. Going back on your comment on access to space as well, I got to experience this a little bit with working on private astronaut missions from the NASA side, and it’s hard to appreciate here in the States as much. But I got to have more of an observation of just the impact, like for example, Eytan working and then bringing that back to Israel and inspiring kids around the country. Now seeing Saudi Arabia and the status that those astronauts have in that country. The inspiration factor I think is a little bit more unique. I think maybe in the States, we’re just used to it. We just have so many different astronauts. But the newness of it, I think is an interesting thing. Maybe something that’s not as valued or talked about for astronauts from other countries. It’s just the impact that an individual or the human in human spaceflight can have on a society.

Michael Lopez-Alegria: I think you unfortunately hit the nail on the head that we’re just, due to our success, we’re kind of used to it unfortunately. But in a lot of these countries, I mean, Alper will be the first human from Turkey to go to the space. He is Yuri Gagarin. He’s John Glenn. I mean, he’s completely unprepared for it. I can tell you, in the most charming way. But he will be a larger than life figure over there. And I did an event with Eytan not too long after our mission and the amount of wildly screaming, crazy excited kids that just see him and light up. It’s spectacular. I mean, we devote that kind of attention to rock stars and artists. But in these countries, astronauts still hold that kind of sway.

Host: You, in a way, have been spending years of your life working on a future of commercial human spaceflight. I think we’re all seeing it shift with these steps like private astronaut missions, working hard on commercial destinations. It’s all part of NASA’s vision as well a robust commercial low Earth orbit economy. And it’s got to start somewhere. Private astronaut missions being one of them. I’m curious to hear your perspective, cause you’ve been so close to it for so many years, from those early conversations to now, how do you feel about the progress of commercialization human spaceflight in low Earth orbit and your thoughts about where we’re going in order to achieve what we’re trying to achieve?

Michael Lopez-Alegria: Well, I often use this analogy about how governments open new frontiers, and then once you’ve got a way to get there and it’s safe, then it’s time for governments to move out the way and let commerce come in and do something there, make a marketplace out of it. And that’s happened over and over again in history. And that’s what’s happening in low Earth orbit. And I think that’s appropriate. NASA and the other agencies are going to go back to the Moon and one day on the Mars. They want to continue to have a footprint in low Earth orbit, but they don’t need to own the infrastructure there. They can buy it as a service just like they’re doing with commercial cargo and commercial crew to the ISS today. So this is a future, the immediate future I think, of commercial human spaceflight in orbit.

I have seen, as you point out, NASA has been fairly bold in its steps that it’s taking toward the commercialization. Definitely not as bold as some would like, but when you consider the size of the organization, you know, I liken it to a giant aircraft carrier that it takes time to change course. And I’ve seen the course change, you know, a few degrees over time. And at some point, it’ll start changing faster and faster. And I think that is a function of just how close the retirement of the ISS is, whether for mechanical or political reasons. But one of those two things is going to limit the life of the ISS. And they will recognize the fact that NASA still wants to have a place to send its astronauts to continue the microgravity research. Not only that, but also to have a training ground. I mean, do you want an astronaut’s first mission to be landing on Mars? Probably not. As that imperative approaches, facilitating that transition becomes more important. And the ISS program in particular, I think has been very forward-leaning in understanding that connection and facilitating that transition. But, you know, we still have a long way to go, but we’re on PAM three and there’ll be probably many more before the ISS is retired.

Host: Yeah. Taking it on home, focusing on Ax-3 and this upcoming mission, you’ve got experience on shuttle, you’ve got experience on long duration station missions, and you have a private astronaut mission under your belt. Particularly I guess from the difference from Ax-1 to Ax-3, how are you going to approach this mission a little bit differently as commander, as your role with the astronauts now that you’ve known and gotten to know them over time with training? What’s your approach going to be like?

Michael Lopez-Alegria: Well, I think because of the changes that we’ve made since Ax-1 and implemented on Ax-2, I will be focused much more on helping the rest of the crew get through what they have to get through. I think I was guilty of a little bit of the Expedition 14 commander mentality when I knew that my crew mates knew exactly what to do, and I worried a little bit about getting my own work done. Perhaps on Ax-1 to the detriment of them getting their work done, or at least getting their work done independently without relying so much on the NASA crew. I think this time will be different. I think we also have the advantage that this crew will have been slightly better trained because of the changes that we’ve made in the training program, especially at NASA, and that that will lead them to being more successful autonomously. You know, ironically, it’s all going to happen at once, but if we’re successful, if all of these things come together as I think they will, we will be wildly successful in executing everything we’re trying to do.

Host: Excellent. To the next private astronaut missions that come, to the folks that are trying to push the boundaries and make sure that we’re continuing this progress. And you’re given your experience with working so much with commercial entities and setting the groundwork for where we are today with Ax-3, what advice do you have for that next set of astronauts that’s going to come, that’s going to have to represent their country, those next folks that are going to be working on the next private astronaut missions and moving forward, what pieces of advice do you have?

Michael Lopez-Alegria: I would say my advice isn’t so much for the crew members. Some of them will be customers and some of them will be proxies of the customers who will be their governments. But rather for the customers themselves, which is: come on down, I think we are really homing in on the right solution on how to manage these projects now, both from a customer experience standpoint to working with our partners, be they NASA or SpaceX or others. And the time is right. I mean, this is sort of the beginning of the snowball starting to roll down the hill. I think as we gather steam, it’s going to become exponentially more and more popular, which is good for everybody. I mean, this is going to help facilitate this idea of expanding access, which is really the fundamental root of what we’re trying to do with these PAM missions, and then later with the Axiom Station.

Host: Wonderful. Absolutely fascinating conversation. Mike Lopez-Alegria, thank you so much for coming on Houston We Have a Podcast, sharing this perspective and your journey that led you to Ax-3. Godspeed.

Michael Lopez-Alegria: Thank you, Gary.

[Music]

Host: Hey, thanks for sticking around. Hope you learned something today. It was an absolute pleasure to be speaking with Mike L.A. today. Lots to learn and lots to do really for commercial spaceflight. You can always check out the latest nasa.gov and you can check out any of our podcasts. We’ve talked about the International Space Station and a lot that’s going on there on our podcast available at nasa.gov/podcasts. While you’re there, you can check out the many other shows we have across the agency on social media. We’re on the NASA Johnson Space Center, pages of Facebook, X, and Instagram. You can use #AskNASA on your favorite platform to submit an idea for the show, maybe ask a question. Just make sure to mention it’s for us at Houston We Have a Podcast. This episode was recorded on October 31, 2023. Thanks to Will Flato, Dane Turner, Abby Graf, Jaden Jennings, Dominique Crespo, Alexis DeJarnette, and Meridyth Moore. And of course, thanks again to Michael Lopez-Alegria for taking the time for coming on the show. Give us a rating and feedback on whatever platform you’re listening to us on and tell us what you think of our podcast. We’ll be back next week.