Introducing NASA’s Curious Universe

Our universe is a wild and wonderful place. Join NASA astronauts, scientists, and engineers on a new adventure each episode — all you need is your curiosity. Explore the lifesaving systems of space suits, break through the sound barrier, and search for life among the stars. First-time space explorers welcome.

Episode Description:

Wherever you live on Earth, wildfires touch your life. They shape ecosystems, clearing dead plants and making way for new. Their smoke changes the air you breathe, and even the climate. And as the Earth warms, wildfires are becoming more frequent and intense. To track a global problem, we need a global perspective. Explore how NASA scientist Doug Morton and Canadian firefighter-turned researcher Josh Johnston use satellites to track the changing landscape of wildfires from space.

Subscribe

[[Sound of crackling leaves/branches]]

Doug Morton

For a fire, you just need three ingredients. You need something to burn.

[[Sound of falling firewood]]

Doug Morton

You need weather conditions that are dry enough to allow that fire to happen. And you need an ignition.

[[Sound of match strike missed, match strike that catches, and flames burning]]

[Song: Anxious Elements Instrumental by Burn Huber]

Doug Morton

There’s always a fire burning someplace on Earth. And we know that because we have satellites that give us coverage of the whole globe every day.

Doug Morton

Every year from space, we detect more than a million large fires. And a large fire in this case might be something the size of 40 acres or larger. Each of those fires represents those same common ingredients that are needed to burn. And most of those fires are started by people. Fires that spread over many days actually account for most of the burning we will ultimately detect and map from space. Those fires are more typically called wildfires, because they’ve escaped the management control and burned for many days.

[Theme Song: Curiosity by SYSTEM Sounds]

HOST PADI BOYD: This is NASA’s Curious Universe. Our universe is a wild and wonderful place. I’m your host Padi Boyd and in this podcast, NASA is your tour guide.

HOST PADI BOYD: Wildfires are extremely destructive forces of nature. When they get out of control, they can burn down buildings and destroy forests. With climate change, wildfires are becoming more frequent and more destructive and burning in places they never have before.

HOST PADI BOYD: NASA, NOAA and other government agencies use satellites to track fires from space. With a view from above, we can prioritize, on a global scale, which fires need to be put out, and which can keep burning without harming anyone. In this episode, let’s learn about wildfires, how NASA tracks them from space, how they’re changing with our climate, and how they can affect you, no matter where you live.

[Song: Churning Doubts by Burn Huber]

Doug Morton

Our satellites have incredible sensitivity to detecting active fires, even very small fires, the kind of thing that you might not think would be detected. No, we don’t know whether you’ve got the grill on in the backyard. And no, we don’t know about your new fire pit. But yes, a fire that might be the size of half a tennis court is big enough for us to be able to detect with our satellite sensors on orbit.

HOST PADI BOYD: Did you recognize that voice? That’s Doug Morton, a NASA Earth scientist and a guest on our very first Curious Universe episode, back in season one.

Doug Morton

Sometimes we describe a fire as a wildfire. That typically means it’s a fire that’s burning out of control. That doesn’t mean it was started by a human or started by lightning. In fact, we often don’t know the cause of most of the fires we see from space. We do know their impacts on ecosystems, communities, and on the emissions they release and how that influences both quality of the air we breathe, and the impact of greenhouse gasses on climate change.

HOST PADI BOYD: Tracking wildfires is a major international effort that involves a lot of collaborators, from NOAA to fire management organizations, and even other space agencies.

Doug Morton

As a NASA scientist, I work very closely with scientists across the U.S. Federal Government, other governments around the world, with the entire science community that’s working to better understand how fires are changing ecosystems.

Doug Morton

This is a real community effort. We’re certainly not going it alone. One of the things that makes me motivated every day is that it is part of that larger community of people that are working hard, to try to do the best they can to learn, understand and adapt to the changing reality of fires.

HOST PADI BOYD: A key collaboration for Doug and his team here at NASA is the collection of research scientists at the Canadian Space agency, or CSA.

[Song: Wild Fires Instrumental by Unwin]

HOST PADI BOYD: No one knows how hard it is to track wildfires on the ground, and how important it is to map them from space, better than Josh Johnston. Josh worked on wildfire satellites for the CSA and the Canadian Forest Service. But he started his career in a very different role: as a wildland firefighter in remote northern Ontario.

Josh Johnston

I am formerly a firefighter. I was an incident commander, seven years on fire crew. I don’t want to say predestiny is how I got into it. But I actually come from a family of firefighters. My father was actually quite well known in the community. My mother even was a dispatcher briefly. And despite her best efforts, we did follow in my father’s footsteps. My brother is still in the fire program, my sister was one of the clerks, a radio operator there for many years.

[[Sound water hoses hitting a burning wildfire, firefighters digging a fire line]]

Josh Johnston

In this part of the country, fighting fire meant hauling in pumps and hose.

Josh Johnston

Imagine being in northern Canada in a place so remote, that the sound of your pump is such a foreign sound, that moose are coming up to check out what’s going on.

[[Sound of firefighter radio chatter]]

Josh Johnston

It’s brutal work in some ways, right? Because you’re hauling heavy packs, and you’re just doing relay runs through the forest like that. You’re always soaking wet from the hose. And the fire is so hot and dry that you’re always dry at the same time.

[[Sound of sizzling fire fades out]]

HOST PADI BOYD: When Josh started fighting fires, his team relied on trained spotters in airplanes and in mountaintop fire lookout towers to keep an eye out for plumes of smoke. When a lookout spotted some smoke, they’d alert Josh and his crew at the base. Where there’s smoke, there’s fire.

We’d be sitting around the base. If you’re on alert, you’re already kitted up in uniform. If you’re red alert, you got to be airborne in three minutes from dispatch. It’s like you’re holding a lotto ticket, and you’re just waiting for them to call the numbers

[[Sound of helicopter flying]]

HOST PADI BOYD: A helicopter would fly Josh’s team out to fight the fire, dropping them off in the forest, often many days’ walk from the nearest road. These weren’t always large, raging fires you might be picturing. Sometimes they could be really hard to find.

Josh Johnston

I think sometimes people picture you detect a fire, and there’s flames coming up and they’re running away. No, you’re trying to find it when it’s smoldering, and it’s on the ground. Because that gives you time to actually catch it, and try and suppress it.

HOST PADI BOYD: Firefighters only have so many resources, and even from planes, it was impossible to keep track of every new fire and catch it before it got too big. Some fires burned out of control.

[Song: Ice Melt Instrumental by Unwin]

HOST PADI BOYD: That’s when firefighting got really intense, and fire squads would have to use what’s called an air attack. Imagine huge planes carrying tanks of water to drop on the flames. Sometimes, these air attacks still barely made a dent in the fire.

[[Sound of tanker planes flying over a wildfire]]

Josh Johnston

You take off and you’re headed for a fire. And you see it from 50 nautical miles out. And it’s just a big towering black column. There’s no way you’re gonna be able to stop this thing and you’re calling in more resources and air attack and everything. You pull your crew out of the drop zone, they hit it, they knock the flames out of the canopy and the guys run back in with the hose and try and catch it while it’s still low. You only got a few minutes before the next tanker comes in and everyone runs back out.

HOST PADI BOYD: Other times in the mountains, the smoke would get so thick, so close to the ground that airplanes couldn’t fly to keep tabs on the flames. It was raging, smoky fires like these that made Josh wish he had a view from space to track the fire’s spread.

Josh Johnston

If you have a very smoky fire, very smoky region, you can ground all the aircraft in that region for an extended period of time. But the beautiful thing about infrared satellites is they still see through smoke, which is a really handy trait in these sorts of scenarios.

HOST PADI BOYD: If you aren’t a wildland firefighter or NASA Earth scientist, or you just don’t live someplace currently threatened by wildfires, it might be hard to relate to all of this. But whether you live in a big city or a remote forest, wildfires affect you.

HOST PADI BOYD: Maybe you’ve seen the smoke, even far from the fire. After large fires, it can rise from the flames way up into the stratosphere, sticking around for days and weeks at the edge of space.

[Song: Tarvos Instrumental by Holroyd Painter]

HOST PADI BOYD: Canadian fires can often cause hazy conditions across the United States, covering the skies with a thick, dark blanket of smoke.

Josh Johnston

It can circulate everywhere. It’s not uncommon for us good old Canadians to smoke out the southern US or the eastern seaboard. I apologize for that. But it is the nature of the beast.

HOST PADI BOYD: That smoke can affect your health if you breathe it in, and it can have far reaching effects over entire nations.

Josh Johnston

Smoke is one of those things that impacts our society in ways that we don’t even understand. There’s been estimates that the cost of fire management in our country can be as much as two billion dollars a year. But the cost of smoke on our economy can be as much as 20 billion a year.

HOST PADI BOYD: Fires also release greenhouse gasses like carbon dioxide into the atmosphere, which causes our climate to warm up. The warmer and drier the climate, the easier it is for even more fires to start. So, fires don’t just affect individual forests and towns, or even individual countries, they affect the whole world. For a global problem, one that’s changing fast with our climate, we need a global perspective. That’s where satellites come in. They weren’t around when Josh fought fires, but now they’re a major component of firefighting.

[Song: Carbon Sink Instrumental by Unwin]

HOST PADI BOYD: Here’s Doug again.

Doug Morton

As a scientist at NASA, it’s my job to use our amazing satellites on orbit, and our scientific expertise to study how fires are changing our planet.

Doug Morton

With our global picture, we’re better able to understand that fires burn an incredibly large extent of the land surface every year. Something approaching the size of Australia burns every year. And those fires, more than a million large fire events, are something that we can track using our satellite data, to better understand how those fires are becoming more common, more severe, or burning hotter, faster and longer than they have before.

HOST PADI BOYD: So how, exactly do satellites detect fires?

Doug Morton

As our satellites pass over, when we detect a new active fire, what we’re detecting is actually the thermal energy that’s being released from the surface from the combustion process. We’re looking for those areas that are releasing more temperature at the surface than what we would expect for a forest or even a desert.

HOST PADI BOYD: To find hot spots, NASA satellites use infrared sensors. To those special sensors, fires on the ground look extremely bright compared to the ground around them.

HOST PADI BOYD: Once a fire is detected and firefighters are alerted, scientists like Doug can use other data to predict how dangerous it might be.

Doug Morton

Information we have about a new active fire that we detect can be combined with information that we have about the land cover, whether it’s a forest, savanna, an area of agriculture, as well as other information that would help us understand how dry and flammable the vegetation is, or the history of rainfall and what that might mean for the chance that fire could grow and spread over time.

HOST PADI BOYD: After the fire is out, satellites can also assess its impact on the environment, whether the next rainfall on a burned hillside might cause a landslide, or how quickly forests will grow back. Doug can even make predictions about where fires are most likely to occur next, based on how hot and dry the landscape is or where lightning storms are appearing.

HOST PADI BOYD: That’s increasingly important as our climate changes and warms. With more frequent and extreme drought conditions, fire seasons are getting longer. And more intense lightning storms mean more chances for fires to start.

[Song: Searing Heat Instrumental by Unwin]

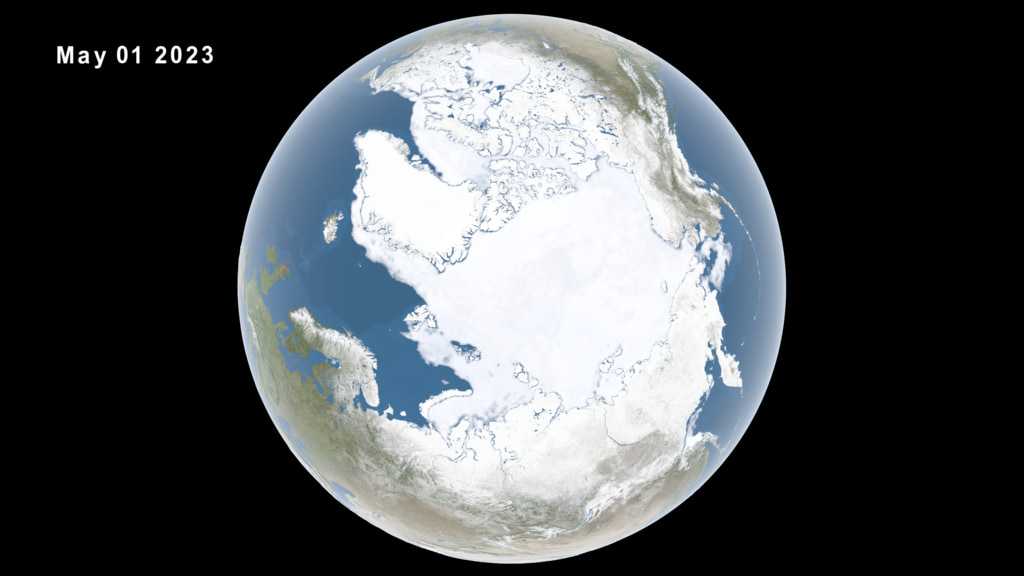

HOST PADI BOYD: Fires are even starting in places scientists thought couldn’t burn, like the Arctic permafrost.

Doug Morton

We’re starting to identify fires in new places that don’t have a long history of fire. Places like the Arctic tundra, where conditions are normally too wet and too cold to allow fires to start. Permafrost, or frozen soils are starting to melt and drain, creating conditions where fires can burn across the surface.

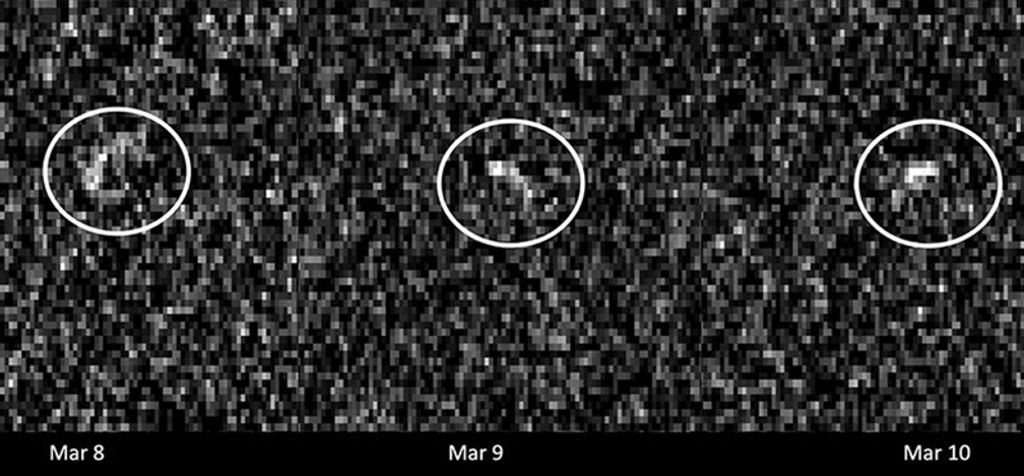

HOST PADI BOYD: Scientists are learning that in some parts of Canada’s boreal forests, fires don’t even go out over the winter when fire season ends. They burn deep down into the organic soil for months.

Doug Morton

This has been one of the more surprising findings in the last several years in the fire science community. So, a fire may overwinter based on its ability to survive with a smoldering through the surface of the soil, and then reignite. It’s not a coincidence when we see those fires in the same place the following year.

HOST PADI BOYD: With more than two decades of observations from space, Doug has detected big changes in where fires are burning. He even has data on how carbon dioxide emissions from fires have changed over that period.

Doug Morton

Fires are one of the most important sources of greenhouse gasses, including from human activity. Together with our understanding of how fire releases specific kinds of greenhouse gasses and aerosols, we’re able to create a model of how fires, on a worldwide basis, are a component of our changing atmosphere.

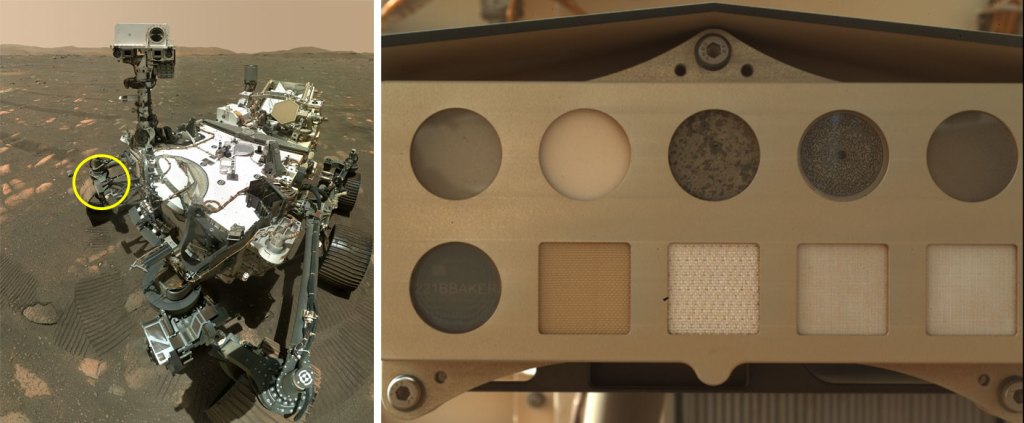

HOST PADI BOYD: Doug uses six NASA satellites to track wildfires. But none of them are fully dedicated to the job. They’re designed mainly to study things like crops, forests and water vapor. We’ve learned so much already from these trusty satellites.

HOST PADI BOYD: But imagine what we could do with one that’s specifically designed to track fires.

[Song: Boomerangs and Palindromes Underscore by Burn Huber]

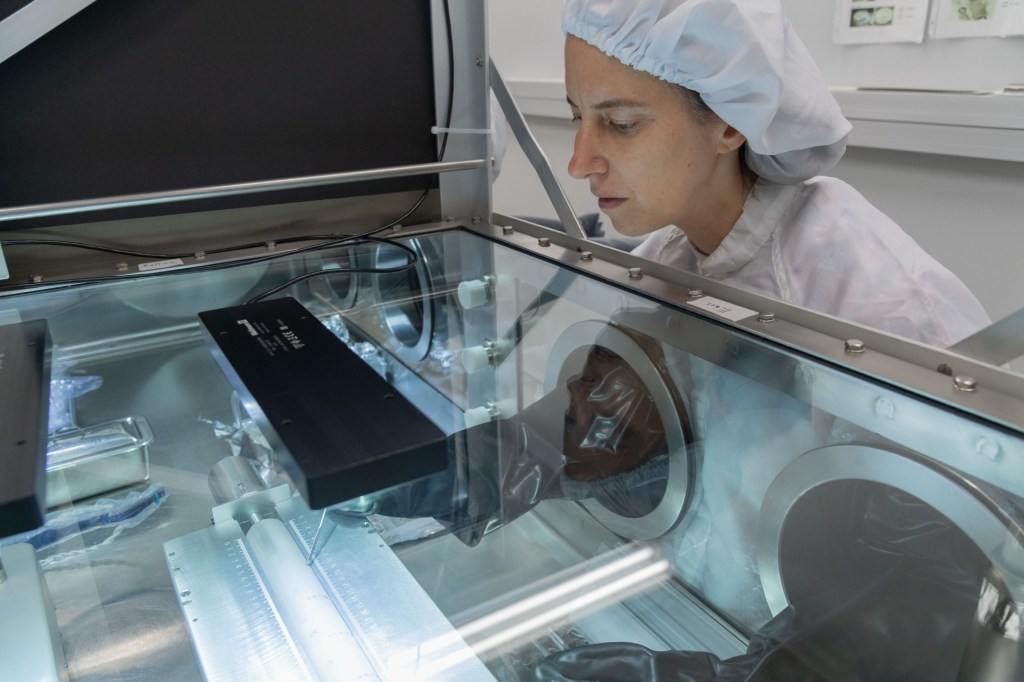

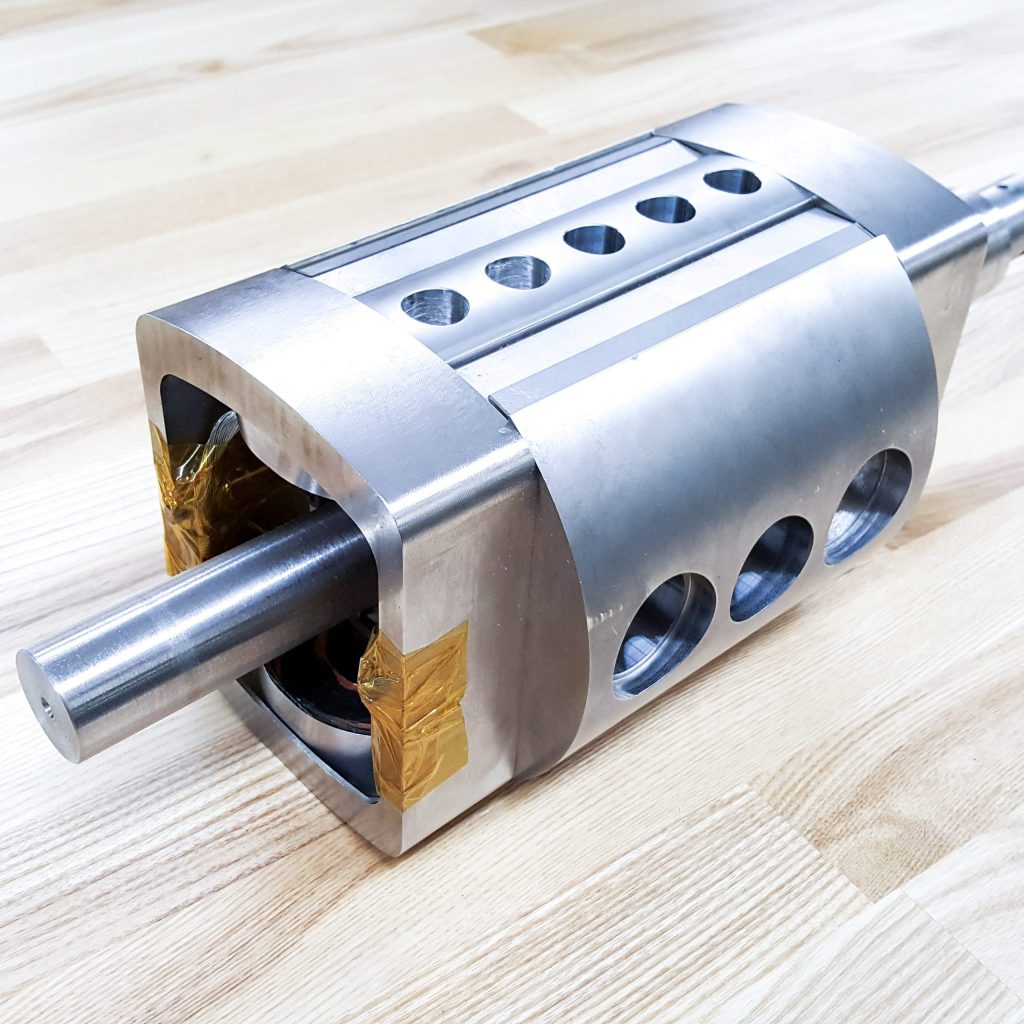

HOST PADI BOYD: Josh, the former wildland firefighter, is the lead scientist on a project from the Canadian Space Agency called WildFireSat. It’ll be the first satellite ever made solely to track wildfires.

Josh Johnston

The real goal of WildFireSat as a satellite mission is to build a satellite for the express purpose of doing this, not as a peripheral benefit that came from a system that was designed for other purposes, no. This is made for this job, we don’t have compromises hiding in there to accommodate other off-topic uses.

HOST PADI BOYD: The team plans to launch the satellite in 2029. With a targeted mission like this, scientists will be able to get richer details on wildfires and their impact on our interconnected, global ecosystem.

Josh Johnston

The goal of the mission is to provide surveillance to track fires. We can tell you how fast it’s moving. We can tell you which direction it’s headed, we can tell you where it’s going and when it’s going to get there. When paired with some of the other science that’s in our agencies, that also allows you to make pretty good assessments about what is the right approach to this fire? Should I fight it? Should I let it go? If I do choose to fight it, What’s the right tool for the job? Do I need bulldozers? Do I need air tankers? Can I just send a crew on the ground?

HOST PADI BOYD: Firefighters can’t fight every fire that starts. Knowing which ones will burn out on their own and which have to be fought is very important in deciding what to prioritize. But to do that, fire managers have to be able to track fires during critical times of day.

HOST PADI BOYD: The best time of day to track fires is six p.m., because the late afternoon is peak burn period. As the sun dries forests out throughout the day, they become ideal fuel for fires. So, later in the evening, fires burn the most intensely.

[Song: Body and Air Underscore by Burn Huber]

Josh Johnston

Fires are strange beasts, they tend to behave a lot like a living creature. They wake up in the morning, and they’re kind of lazy. Around noon, they start to wake up and get real busy, late afternoon, they’re just on a tear. And then if they’re doing what they should be doing, they go to sleep overnight. That’s not always the case these days. And that late afternoon period, when they’re busy, we call that peak burn. That’s when fires are doing real bad things.

HOST PADI BOYD: During their orbital paths, NASA’s current polar orbiting satellites pass over in the morning and early afternoon, missing the peak burn time completely.

Josh Johnston

What we’ve done is put ours right in the middle of that time of day when fires are at their absolute peak activity.

HOST PADI BOYD: The new Canadian WildFireSat will form what’s called a virtual constellation with two NASA satellites, filling in that gap in the data. The three satellites will fly in a formation, working together and providing data at different times of day.

Josh Johnston

During that peak burn period, we now have an observation of where the fire was at the start of it and where it was towards the end of it. Near real time, we can tell people if the fire moved during peak burn, how far did it go and which direction did it go.

HOST PADI BOYD: Things have definitely changed a lot since Josh was a firefighter. Back then, the little bits of information firefighters got from planes and on-the-ground reports were enough.

Josh Johnston

Back then I would just get briefings and the briefings would say things like, “X fire, 50,000 hectares, not under control.” But that’s literally all the intel I would ever see.

Josh Johnston

We didn’t have a full picture of each and every one of them, especially the very remote ones.

Josh Johnston

That whole point behind this mission, it’s there to give the decision makers a lot better information to make a decision on, especially under climate change. The decisions are getting harder, the timing is getting shorter.

Josh Johnston

And I think that in terms of doing triage on a day when you have a massive surge of fire activity, like, I can think of days where just in my sector, we would have had 100 fires. If you’re trying to be the guy who’s in the command center determining where you’re going to send air tankers, it would be really, really nice to know if some of those new ones that are coming in in that massive surge you could probably let burn for two weeks, and it wouldn’t matter. That’s the sort of intel that will really change the way operations happen.

Josh Johnston

My father back in ’86, did come home insisting that satellites were going to change the way we did things. And it’s kind of ironic that his son is the one who’s leading that charge now. Slightly different timeline, but he was on point.

HOST PADI BOYD: For Josh, a wildfire satellite would have been nice to have. For the next generation, it’ll be absolutely necessary.

Josh Johnston

It would have been cool when I was in the business. It would have been futuristic stuff when my dad was working.

Josh Johnston

Accepting the reality that my children will almost certainly follow behind us, the number of high pressure decisions is going to go up. The number of those days when you have just a massive surge of fire activity on the landscape and everything’s going wrong, those days are going to go up. For them, it won’t be a novelty, and it won’t be something neat. For them, it will be an absolute necessity. And that’s why we’re doing this. We’re doing this now because we know by the time it gets into orbit, it‘ll be late

[Theme song: Curiosity Outro by SYSTEM Sounds]

HOST PADI BOYD: This is NASA’s Curious Universe. This episode was written and produced by Christian Elliott and edited by Christina Dana. Our executive producer is Katie Konans. The Curious Universe team includes Maddie Arnold and Micheala Sosby.

HOST PADI BOYD: Our theme song was composed by Matt Russo and Andrew Santaguida of SYSTEM Sounds. Special thanks to Jake Richmond and Peter Jacobs.

HOST PADI BOYD: If you liked this episode, please let us know by leaving us a review, tweeting about the show @NASA, and sharing NASA’s Curious Universe with a friend. And, remember, you can “follow” NASA’s Curious Universe in your favorite podcast app to get a notification each time we post a new episode.

Josh

The number of times that we’ve been out there, and we’re nozzling on a fire, and just out of nowhere, a moose just wanders over, and he’s like, “Hey, what’s up,” and you’re like, “Whoa,” you know, because like, we’re all hunters too, eh. And you never see that when you’re actually hunting.