Our universe is a wild and wonderful place. In this season, we’ll learn about lunar mysteries, break through the sound barrier, and search for life among the stars. First-time space explorers welcome.

Episode Description:

Scientific experiments can often benefit from a little bit of space…outer space that is! To get there, dozens of fast-launching, instrument-carrying rockets are launched across the globe every year. Explore sounding rockets, and the experiments they take to the skies, with space physicist Alexa Halford and sounding rocket program assistant chief Cathy Hesh.

Subscribe

[Song: Rivers Mountains Alternative Version by Hansson]

Cathy Hesh

The beginning of a launch day is always very exciting. There’s a lot of anticipation about what’s going to happen.

Cathy Hesh

During the first two to three hours of the countdown, we’re performing checkout of all the launch vehicle and the payload systems on board. And we continue the countdown and at T-zero, that’s the moment of launch, that’s what we call it, we send the electrical current to the igniter, and the first stage rocket motor and that ignites the first stage.

[Launch countdown and sounding rocket launch audio]

Cathy Hesh

The sounding rocket then reaches speeds that exceed the speed of sound, which is about 700 miles an hour within a few seconds after launch. If you blink too fast, you’ll miss it.

[[Sounds of crowd cheering at launch]]

Cathy Hesh

Then the upper stage continues to burn as we move through the upper atmosphere and we reach the space environment about one to two minutes after launch depending on the size of the vehicle.

Cathy Hesh

You can see the second stage ignite and then if you pay real close attention, you can actually see the first stage booster reentering back down and it makes a whistle sound that you can hear.

[[Whistle sound of sounding rocket]]

Cathy Hesh

And if you get a nice view through the seawall, you can actually see the first stage impact the water as it goes into the ocean. So that’s one of my favorite things to do when I go to a launch is to see if I can spot that booster coming back in and then hitting the water.

[[Ocean sounds]]

[Theme song: Curiosity by SYSTEM Sounds]

HOST PADI BOYD: This is NASA’s Curious Universe. Our universe is a wild and wonderful place. I’m your host Padi Boyd and in this podcast, NASA is your tour guide.

HOST PADI BOYD: Here at NASA, we do quite a bit of space exploring. We send satellites, astronauts, and probes out into the solar system to help us learn more about the universe around us. But these processes all take a pretty long time… to plan, to launch, to travel, and even to get results back.

HOST PADI BOYD: In addition to those long missions, there’s a quicker option used by scientists all over the world, that lets us explore parts of space withoutthe wait time!

HOST PADI BOYD: Sounding rockets are small, instrument-carrying research rockets designed to take measurements in space to test new technology or perform scientific experiments. But instead of spending days, weeks, or even years out in the cosmos – they only travel for around 15 minutes.

HOST PADI BOYD: Their quick but far-reaching trajectory makes them a great vehicle to test out instruments, study the upper atmosphere, observe distant stellar objects, and reach precise destinations far above Earth’s surface.

HOST PADI BOYD: They’ve unlocked some of our most interesting mysteries of the solar system – discovering the first hydrogen atoms in space, taking samples of our ozone layer, and so much more.

[Song: Fellow for Life Underscore by Peterson Thomas]

HOST PADI BOYD: So today, let’s take a look at sounding rockets – and what it feels like to see your experiment blast off for a quick trip into space.

Cathy Hesh

We conduct about 16 to 20 sounding rocket launches all over the world every year. Our job is to collect as much compelling science for NASA as we possibly can.

HOST PADI BOYD: That’s Cathy Hesh, assistant chief of the sounding rocket program office at NASA’s Wallops Flight Facility.

HOST PADI BOYD: With up to 20 launches a year, sounding rockets are a great way to make space accessible to scientists all over the world. If you’ve got a project that needs to experience spaceflight but you don’t have years to wait, a sounding rocket could be just the vehicle for you!

HOST PADI BOYD: And it’s not just how many we launch, but what the rockets themselves are like that allows for this rapid rate of experimentation.

Cathy Hesh

Sounding rockets are much smaller than the typical space rockets that you’ll see on TV, the Saturn rocket or some of the large SpaceX Falcon rockets. A sounding rocket is small. They can be up to about 70 feet in length, which is about the size of two school buses put together; about a six or seven story building.

Cathy Hesh

But they’re only about two feet in diameter. So we can only fit small things inside: small scientific instruments, small electronics.

Cathy Hesh

They are incredibly fast. A lot of the space launches on television, the big rockets are very slow to leave the pad…

[[Large, space rocket launch sound]]

Cathy Hesh

Where sounding rockets leave the pad in the blink of an eye and are going very fast.

[[Sounding rocket launch sound]]

Cathy Hesh

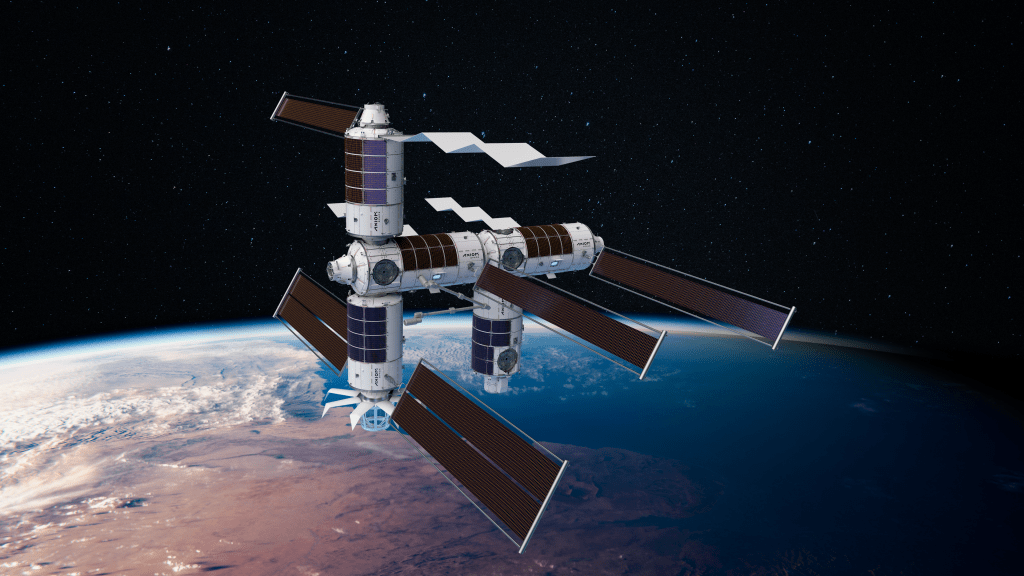

Typical sounding rocket flights last around five to 15 minutes total, to altitudes that range from 60 miles above Earth’s surface all the way up to 850 miles above Earth’s surface. And to put that into perspective, the International Space Station orbits at an altitude of about 250 miles. So although sounding rockets are small, we can reach altitudes that are three to four times higher than the Space Station orbits. We just don’t stay up there very long, we only stay up there maybe five minutes.

HOST PADI BOYD: The term “sounding rocket” doesn’t mean they’re particularly noisy. It comes from the nautical term “to sound” or to take measurements. In under 15 minutes, these rockets blast off, take their measurements, and then return back to the ground where scientists unpack all that new information.

[Song: Enter With Purpose Instrumental by Featherby McAvoy]

HOST PADI BOYD: There are quite a few tools we can use to measure the atmosphere and our outer space surroundings: planes, satellites, and even balloons!

HOST PADI BOYD: But sounding rockets are designed to reach heights that other vehicles can’t.

Cathy Hesh

Scientific, high-altitude balloons can maybe get to about an altitude of100,000 feet. Satellites can orbit, you know, up around that 250-mile point, but there’s not a lot of platforms that can reach altitudes in between those two. And that’s kind of where sounding rockets really are a great platform to use for science studies in that particular altitude range.

HOST PADI BOYD: These speedy rockets can be equipped to carry a variety of instruments, cameras, and telescopes up into the atmosphere. We call this the “payload“. These instruments record and send back fascinating data for our scientists to dig into!

HOST PADI BOYD: But there’s something these rockets are not well-suited to transport, and that’s the scientists themselves. Sounding rockets are uncrewed, meaning no one is inside them during a launch. They wouldn’t be a very pleasant place for a human.

Cathy Hesh

Right off the pad, we see the sounding rocket accelerate to 20 G’s in almost a second, and in flight, they’re spinning very fast, four to five times around in a second.

Cathy Hesh

We often fly onboard cameras for our sounding rockets and it has a dizzying effect when you’re watching the onboard video. So it’s not a place where people would want to be and likely would not survive.

HOST PADI BOYD: Each sounding rocket launch is unique but there are some steps that remain the same. After the rocket is launched, it shoots up into the sky unguided, counting on the power of its rocket boosters and calculations of the wind to keep it on course.

HOST PADI BOYD: Once in the air, the rocket spins incredibly fast. The payload, full of instruments, separates from the motor and boosters, which shoot it from the pad.

HOST PADI BOYD: When it reaches its apogee, the highest point in the journey, the payload takes in all the data and measurements scientists are looking for before falling back to Earth. From there, the team can often get that payload itself back after it has landed, or simply use the data it sent down during flight.

HOST PADI BOYD: That whole process takes less than 15 minutes. But the process of planning and designing the experiment is also relatively short compared to some other missions.

Cathy Hesh

We do our missions in as short as six months. But most missions typically take about two years from start to finish. Considering other platforms that we use to study space science, that’s a pretty rapid turnaround that we can do.

HOST PADI BOYD: With more opportunities to launch, scientists use sounding rockets to study many different areas of space science. They can test new equipment in microgravity, take in information about space physics, and even monitor and explore the star of our solar system – our Sun!

[Song: With A Pop Underscore by McAvoy Peterson]

Cathy Hesh

We’ve done about 700 missions since the early 1980s. And hundreds of scientific papers have been published based on data collected from sounding rockets.

Cathy Hesh

Sounding rockets are used to support a lot of different science disciplines. We do a lot of solar physics studies where they’re studying the Sun. We’re studying Earth’s atmosphere and how that interacts with the Sun. And we do astrophysics as well, which is the study of stars and other celestial bodies in space. We did a mission for the supersonic parachutes a few years ago that were used on the Mars 2020 mission recently. We also use them for technology development, and we also use them for student outreach. We do two student missions a year, where they build and assemble sounding rocket payloads. We fly them and they’re able to get their experiments and instruments back after the flight.

Cathy Hesh

Sounding rockets are a great way to study heliophysics. They can fly these high-resolution telescopes, where they can see solar events, the loops coming off of the Sun, they can see sunspots, all these events going on on the Sun, and really take a lot of incredible data.

HOST PADI BOYD: As with any spacecraft, sounding rockets need to launch at the right place, at the right time. So scientists think hard about what they’re trying to discover and when they’ll have the best possibility for success.

Cathy Hesh

A lot of our missions require certain conditions. We fly a lot of missions that want to study the aurora. So they might need to go out of Alaska or Norway, where they have an active aurora going on. And a lot of times they want to fly in certain times of year when they know that that aurora is going to be active in that region.

HOST PADI BOYD: The aurora, also known as the northern or southern lights, is the beautiful display of colorful light that can sometimes be seen dancing across the night sky.

HOST PADI BOYD: Cathy and her team coordinate with scientists who have big questions about our universe. They provide them the support and logistics to get their experiments into space.

[Song: Inquisitive Spirit Instrumental by Featherby McAvoy]

HOST PADI BOYD: One of those scientists is Alexa Halford, who studies how the Sun’s activity, such as solar storms, might impact us on Earth.

Alexa Halford

It has weather just like terrestrial weather that we have here on Earth. We’re looking at how these storms that are coming from the sun, or even storms here on Earth, or even just mountains here on Earth end up impacting and changing the dynamics in space, so that we can better protect astronauts and satellites and other infrastructure affected by these kinds of phenomena.

HOST PADI BOYD: Alexa just experienced her first sounding rocket launch for a project studying the particles of the aurora that are created by Earth’s interactions with the Sun.

HOST PADI BOYD: It’s fascinating just to look at the aurora from our vantage point here on Earth. But studying it is a challenge, unless you have a way to get a little closer to the action.

Alexa Halford

So it turns out that sometimes you want to be above the atmosphere so that you can see the stars better or maybe you want to get to very specific points in the atmosphere, which are hard to get to using either balloons or satellites. And so the rockets allow us to kind of get to these harder-to-reach places, when we want to see firsthand what’s actually happening during different types of space weather.

Alexa Halford

We were looking to get back a lot of data, looking at different particles. Our science question that we were looking at is about the pulsating aurora, and this is one of the most common forms of the aurora. It’s often though, overlooked by a lot of people who go out hunting to see the aurora at night.

Alexa Halford

When you see pictures of the aurora, you often see those kind of rivers of green, that are kind of flowing through the sky. Or if you’re looking straight overhead of a breakup, a region where the aurora kind of like grows and then it all of a sudden like explodes into color.

Alexa Halford

But once that all kind of starts receding, you have these big patches of green lights, that kind of pulsate and they just kind of come on and off almost more like a lava lamp.

Alexa Halford

The particles that we’re looking at, they’re many thousands of miles away from us. And then they’re coming down into the atmosphere and into the earth. And so we’re trying to catch them right before they hit the atmosphere.

Alexa Halford

They’re creating that light somewhere at around 100 kilometers, 10 times as high up as airlines are flying. And so the rocket really helped us kind of get that part of the picture. As the rocket goes up, it will see the particles coming down right before they hit the atmosphere. And then the cameras are going to capture the light that those particles helped create inside the atmosphere.

HOST PADI BOYD: Alexa’s project launched out of Alaska in spring of 2022. Setting up a sounding rocket and launching it at just the right time takes patience and prep work. And because Alexa’s team were studying a night-time light show, it also meant working unusual hours.

Alexa Halford

You come a little bit early before your launch window opens. So our launch window was two weeks long.

[Song: A Ponderous Fox Instrumental by Featherby McAvoy]

Alexa Halford

We would come in every night at 8 p.m. and get ready so that we could have the potential to launch from midnight to 4 a.m. Alaska Standard Time.

Alexa Halford

We tested, made sure everything was working, made sure the data was looking good. And then our first launch night, we go through like a practice countdown. Does the data look alright? Does the communications look right? Does the GPS look like it’s working properly? Do the instruments on board look like they’re going well? And then you practice the launch itself. And that was terrifying the first night that we did that. Because all I could think is: I don’t want to say, ‘Go’ because I don’t want us to go, we’re not supposed to go and I know it’s just a practice, but still.

[[Launch chatter begin: “ACS Check one-two-one… check one-two-zero… TMA check one-two-two”]]

Alexa Halford

We were practicing, 15 minutes looked ok so we said, ‘Keep going through.’ And then all of a sudden, our data started looking bad. I couldn’t remember what I was supposed to say. So I think I started saying everything: ‘no, stop red red no hold hold!’ That’s the problem with being a first time principal investigator is you don’t know the language you’re supposed to use. And thankfully, that got across what my concern was. We actually had to pull the rocket off the launchpad and take it down and start taking it back apart so that we could see what was going on with the data.

HOST PADI BOYD: After that practice run, it was time for the team to get everything fixed up and monitor the night sky for the best aurora to study. While sounding rockets are faster and more affordable than other rockets, the team still only had one chance to measure the aurora after launch.

Alexa Halford

A few nights later, we started seeing some good activity come.

[[Control room audio from 3/4/22 begins: “…What is the science report? That there is amazing aurora outside right now”]]

Alexa Halford

One of the other scientists on the team, she told me that night she’s like, ‘I have a knot in my stomach. And every time I have a knot in my stomach, we launch that night’. We started looking at what the ground based observations were seeing, and it’s like, this is going to be good.

[[Control room audio from 3/4/22 continues: “…Thank you and this is – this is really cool. I have no more words. It’s really pretty…Alright, for those of you that have a minute and want to go check out the aurora, better do it quickly.”]]

[Song: Lurking in the Woodlands Underscore by Featherby McAvoy]

Alexa Halford

Everyone started getting more excited, people kept jumping into the science operation center where we’d make this call.

[[Control room audio from 3/4/22 continues: “…We are standing by waiting for you, ma’am, thank you.”]]

Alexa Halford

We had people down in Venetie, this town north of Fairbanks, and they were going to tell us when they saw those pulsating aurora with that flickering, that fast kind of moving stuff inside of it. And that’s when we’re gonna launch. We would have them call in about every half hour just to check in. All of a sudden, we got a phone call that was not on the half hour: ‘We see pulsating aurora.’ I think I hung up and said, ‘We’re going to launch!’. I just picked up the other phone and called down to the launch pad and said, ‘We are go for launch, let’s pick up the count.’

[[Control room audio from 3/4/22 continues: “…Go ahead ma’am…we are asking to drop the count…do you copy?”]]

Alexa Halford

And then everything started happening really, really fast. Everyone ran back up to their stations, making sure that all the screens were working, making sure everything was going, we went through the rest of the count.

[[Control room audio from 3/4/22 continues: “…All stations, this is CM on channel two reporting a go-status. Programmer?…Programmer, go…PI?…PI, go…MM?…MM, go…One minute and counting…60 seconds”]]

Alexa Halford

And a friend of mine had given me a tip. In the science operation center, you’re in a room without windows. You’re not going to be able to see the rocket launch itself, right? And so she said it takes 12 seconds to run from the science operation center out to a platform that faces the launch pad where you could then see the rocket being launched from. And so she made me promise that at T-minus 12 seconds, as long as everything still looks good, to run out there and watch my rocket.

Alexa Halford

So I did just that! I sat there and I waited and I waited until, you know, everything still looked good. And it’s like at 12 seconds, what more can you do, right? You can sort of stop it. The people down at the launch pad are going to notice if something’s wrong just as much as I would.

Alexa Halford

I literally just ran out the door. I told everyone before that to go outside and there was like a little stairway, I said ‘Make sure you’re not in front of that door because I’m coming out and I’m plowing over you!’

Alexa Halford

You could hear the countdown going on outside..

[[Launch audio: “Ten, nine, eight, seven, six, five, four, three, two, one, zero.”]]

[[Sounds of the rocket launching]]

Alexa Halford

It gets a little quiet. And then you hear the big boom, and you see the rocket taking off, and you see it going. And then you see the second stage. And it goes off again. And it was so cool. Because the pulsating aurora can take up a huge amount of the night sky. And not just your night sky, all of Canada and the US’s night sky. So you could watch this rocket going up through the type of thing we wanted to see right in front of you. And that was so cool.

[[Crowd cheering]]

Alexa Halford

When I can no longer see it, when the rocket kind of faded into the distance I ran back in along with everybody else now. And we watched to see what data was starting to come in. There was a huge cheer when we could see that we had caught the type of phenomenon that we wanted to get. That was so amazing, because you never know and you’re never guaranteed for sure, if you’re going to catch what you’re hoping to catch. It might be just off to the side, it might be just a bit North or South. And so that was cool to get that confirmation.

HOST PADI BOYD: Alexa and her team got back tons of information from their rocket flight. They had a camera on board taking pictures as well as instruments transmitting back encoded data – ones and zeros – that will shed light on how these pulsating aurora particles impact our planet.

[Song: Aurora Dance Underscore by Trofimov]

HOST PADI BOYD: Alexa might have had to spend some cold nights in Alaska, but NASA launches sounding rockets all over the world, from sites across the US to Norway, Australia, the Marshall Islands and more.

HOST PADI BOYD: Cathy works out of NASA’s Wallops Flight Facility, on the eastern coast of Virginia.

Cathy Hesh

Wallops is our home range. We do have a wide open ocean, which really allows for a lot of missions to occur because we’ve got a lot of ocean to play with where it’s not going to be near people, and it keeps the public safe.

Cathy Hesh

We also have another launch site out of White Sands, New Mexico that we launch probably about half of our missions from every year. It’s a land-based range. The benefit of that is we can fly out with a helicopter, recover it, and fly all the scientific instruments and the systems again.

HOST PADI BOYD: Sounding rocket launches are a lot of fun and everyone’s invited! You can stop by Wallops for a launch or tune in at home to see how these amazing machines take off.

Cathy Hesh

Our Visitor Center at Wallops Flight Facility is open for most of our launches that we do. That is a little further away from the launchpad, maybe a couple miles. But you still can see the full launch and feel and hear the rumble that you get from the rocket motors themselves.

Cathy Hesh

We also do a live webcast of all of our launches from Wallops. You get to experience sounding rocket launches, right as they’re going on at Wallops.

Cathy Hesh

Sounding rockets is a really fun place to work. We have 40 to 55 missions going on at the same time. It’s always something new, we like to say each of our payloads is like a snowflake. There’s no one that’s identical to another.

Cathy Hesh

Some other space programs you can work a decade before you can see your project launch. With sounding rockets, it’s very quick. It can be six months to two years, and you’re constantly getting to see your work be launched.

Cathy Hesh

It’s very exciting when we get to go see our scientists present at their conferences, the interesting and new discoveries that they’ve made through sounding rockets, all the things that they’re studying and have learned just by that little bit of work that you contributed, really makes a difference in terms of what the scientists have achieved…

[Song: Curiosity Outro by SYSTEM Sounds]

HOST PADI BOYD: This is NASA’s Curious Universe. This episode was written and produced by Christina Dana. Our executive producer is Katie Atkinson. The Curious Universe team includes Maddie Arnold and Micheala Sosby with support from Caroline Capone, Julie Freijat, Juliette Gudknecht, and Erica Kriner.

HOST PADI BOYD: Our theme song was composed by Matt Russo and Andrew Santaguida of System Sounds.

HOST PADI BOYD: Special thanks to Jamie Adkins, Denise Hill, Miles Hatfield, Joy Ng, and the heliophysics team.

HOST PADI BOYD: If you liked this episode, please let us know by leaving us a review, tweeting about the show @NASA, and sharing NASA’s Curious Universe with a friend.

HOST PADI BOYD: Still curious about NASA? You can send us questions about this episode or a previous one and we’ll try to track down the answers! You can email a voice recording or send a written note to NASA-CuriousUniverse@mail.NASA.gov. Go to nasa.gov/curiousuniverse for more information.

HOST PADI BOYD: And, remember, you can “follow” NASA’s Curious Universe in your favorite podcast app to get a notification each time we post a new episode.

[[Radio chatter begins:

Uh CM this is TMA on channel 2.

Go ahead, sir.

We’re wondering since we’re waiting on a cascade, uh, a TM tech just had a birthday today. We’re wondering if you wouldn’t mind joining us in wishing, uh, Justin a happy birthday?

We can certainly do that. Do you want to sing that, sir?

We would love to.

[Singing happy birthday]

Everybody join in!

[Singing]

Do not take it on the road. Happy birthday, Justin.

Happy birthday. I think we might all want to keep our day jobs or night jobs or whatever job this is.

…Everybody’s a critic!

Thank you, CM, that’s, um, much appreciated.]]