NASA’s Curious Universe

Season 3, Episode 3: “Interpreting our Universe”

Introducing NASA’s Curious Universe

Our universe is a wild and wonderful place. Join NASA astronauts, scientists and engineers on a new adventure each week — all you need is your curiosity. Fly over the Antarctic tundra, explore faraway styrofoam planets, and journey deep into our solar system. First-time space explorers welcome.

About the Episode

You’ve probably seen beautiful images of space taken from telescopes around the world and out in orbit. But how does a bunch of intergalactic information become a vibrant photograph? And what else can we see, feel, and hear from that data? Scientists Kenneth Carpenter, Kimberly Arcand, and Denna Lambert help us translate the universe.

Subscribe

Kimberly Arcand

So the very first time we worked on the center of our Milky Way galaxy, it just sort of blew my mind, the very first listen through of this piece was incredible.

[Sonification swells]

Kimberly Arcand

It’s this rich field, about 400 light years across of the very core of our Milky Way galaxy. When you hear it, there’s this incredible crescendo over on the right side of the data set. And that crescendo with all of these little beeps, and boops going on is essentially all of the area around the supermassive black hole at the very center of our Milky Way galaxy.

[Sonification swells and fades]

Kimberly Arcand

And it’s incredible to be able to hear it because it feels so much more powerful to be able to hear that data versus just looking at it.

[Theme Song: Curiosity by SYSTEM Sounds]

HOST PADI BOYD: This is NASA’s Curious Universe. Our universe is a wild and wonderful place. I’m Padi Boyd, and in this podcast, NASA is your tour guide!

HOST PADI BOYD: As you might imagine, NASA scientists spend a lot of time looking at numbers. From huge tables and spreadsheets to complicated diagrams – there’s a lot of math involved.

HOST PADI BOYD: But one of the coolest things about studying space is when those numbers turn into a beautiful piece of art.

HOST PADI BOYD: You’ve probably seen vibrant images of our universe, maybe in a science textbook or on a t-shirt. These photographs are often based on information collected by telescopes and instruments in space.

HOST PADI BOYD: With ever-improving technology, we can learn even more about our universe from these images…and figure out new and interesting ways to use the data we’re collecting. We can translate the information into things we can hear…and even touch.

[Song: Pixel Perfect Underscore by Todd James Carlin Baker]

HOST PADI BOYD: In this episode, we’re going to look at how NASA scientists bring data to life – in captivating and surprising ways.

Ken Carpenter

Hubble data is used in a huge variety of ways, and people are getting more imaginative perhaps as the years go on.

HOST PADI BOYD: That’s Kenneth Carpenter. He works as the Hubble Space Telescope operations project scientist. Hubble has been orbiting just above Earth’s atmosphere since 1990.

HOST PADI BOYD:With a clear view of the universe, the Hubble Space Telescope sends us iconic images of space. Chances are, whether you realize it or not, the images you imagine when you think of the cosmos probably came from Hubble!

Ken Carpenter

Perhaps the most impressive thing of Hubble is the the way it’s impacted both science and popular culture. I think the biggest value of Hubble has been its ability to inspire people to go on to science and technical careers, to understand the universe, but also just to appreciate the beauty of the universe.

HOST PADI BOYD:Hubble was launched on Space Shuttle Discovery and put into orbit by a group of astronauts. It has since been upgraded five times by astronaut servicing missions. But unlike a backyard telescope, no one has ever looked “through” Hubble; that’s not how this telescope works.

Ken Carpenter

Everything is done digitally so it’s sending down a string of numbers. And then that has to be reconstructed on the ground.

Ken Carpenter

People are used to seeing these brilliant, gorgeous color images. Unlike a cell phone camera, it doesn’t just take a snapshot and get it in color. The pictures that Hubble takes are actually what are called monochromatic, single color.

Ken Carpenter

They look black and white, but they could be actually observed at different colors all the way from the ultraviolet, which is bluer than the eye sees and bluer than gets through the Earth’s atmosphere, through the visible that the eye does see, out into the infrared, which again, the eye isn’t sensitive to all the different colors in the infrared. And a lot of it doesn’t get through the Earth’s atmosphere either.

Ken Carpenter

So if we actually want to see a full color image, we take multiple pictures. And in the simplest case, we take a red, a green and a blue. You take these three pictures and mix them together to get the overall color balance.

Ken Carpenter

You have to pull in the ultraviolet and infrared colors into the visible spectrum. So what we usually do is keep the colors in the right order, but just bring them a little closer together so they all fit.

HOST PADI BOYD: Because we can’t see the colors in the ultraviolet and infrared parts of the spectrum, NASA scientists use the closest approximation of colors in the visible light spectrum to represent that information.

HOST PADI BOYD: Hubble is fully digital, recording information in space and sending it down to our computers here on Earth. But NASA has been working on Hubble for quite a while now…before digital cameras existed.

[Song: Strawberry Moon Instrumental by Hussain Kaid and Thomas Pritchard]

Ken Carpenter

Way back in the 60s, when Hubble was first being thought about and, and designed, there was apparently a concept for using actual film. We found this figure that had been shown in presentations that shows a cutaway of the telescope. And it shows a person floating in the back end of the telescope pulling out a film canister.

HOST PADI BOYD: That’s a fun scenario to think about, but not what actually ended up happening. Instead, since 1990, Hubble has been sending back information about our universe digitally and remotely.

HOST PADI BOYD: While Hubble is NASA’s longest-running space telescope, it’s not the only observatory gathering information from space.

[Song: Wonderland by Dolph Taylor, Harry Douglas, and Russell Emanuel]

Kimberly Arcand

Hi, I’m doctor Kimberly Arcand and I am a visualizations scientist for NASA’s Chandra X-Ray Observatory. Essentially I get to use data to tell stories of our universe.

Kimberly Arcand

I really wanted to be an astronaut when I was a kid but then quickly found out that would not be a suitable career for me since I could barely handle like the tilt-a-whirl at an amusement park. But eventually found my way into coding and coding for me was just kind of a way to kind of help tell stories about science and I landed my first real job working for Chandra right before Chandra was about to launch.

HOST PADI BOYD: The Chandra X-Ray Observatory is another telescope orbiting out in space that gives us a deeper understanding of our universe.

Kimberly Arcand

Chandra is a sister telescope to the Hubble Space Telescope, it goes about a third of the way to the Moon. And though it’s never had a servicing mission, it’s been working really beautifully for the past 20 plus years.

HOST PADI BOYD: Like its name suggests – the Chandra X-ray Observatory takes in information about the x-ray part of the spectrum. That part of the spectrum is even bluer than ultraviolet light, neither of which the human eye can see.

Kimberly Arcand

You could picture an object in outer space like a supernova remnant, say 10,000 light years away. That light, that X-ray light from the object, has been traveling towards us for quite some time, and Chandra is essentially pointed towards it. Now that information that’s been traveling from that exploded star, it’s collected down in the Chandra spacecraft and then essentially formed into ones and zeros. It’s encoded into binary code and then sent down through NASA’s Deep Space Network about every eight hours till it lands at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in California, and then eventually goes on its merry way to our laptops here in New England.

Kimberly Arcand

Once we get the data here at the Center for Astrophysics, then essentially we use software to translate that information from all those ones and zeros into some sort of other piece of information. For example, it might be a table that tells you all of the locations and the energy levels. Or you might take it a step further and create the visual representation of that object as well. Typically, what we’re doing is taking that data and then translating it into some sort of image of, say, the exploded star. And then scientists are using all of, like, the spectral data, the sort of DNA or the the fingerprint of that information, in order to analyze and understand what’s happening inside or around that object.

HOST PADI BOYD– With this spectral data, scientists can figure out what elements are present in a cosmic object, how far away it is from us, and even how many light-years across it is.

HOST PADI BOYD– Working in the x-ray part of the spectrum provides interesting challenges for understanding and communicating about new discoveries.

Kimberly Arcand

We are exploring the x-ray universe that no human can ever naturally see.

[Song: Echo Space Instrumental by James Alexander Dorman]

Kimberly Arcand

Human eyes cannot detect X ray light, so we have to translate it from one form into another. And we do often prioritize visuals for that. But there’s no reason why we can’t additionally prioritize sound or touch or well probably not smell or taste, but you get the idea.

Kimberly Arcand

We have primarily been creating two dimensional images with our Chandra data, over the past couple of decades. However, we have done other stuff as well, such as time lapse data, where we’re looking at series of information, snapshots, if you will, but collected over time. And then we also started working in three dimensional models about a decade ago. And then most recently, we started taking that information and translating it into sound, and even haptic information, which is touch, like the vibration that you feel on your phone, for example.

HOST PADI BOYD: One of Kimberly’s specialties is using information from these telescopes and translating that information into something called a data sonification.

Kimberly Arcand

I like to say that data sonification is the process that translates data into sound. We’re not capturing sound information that the universe is sending out to us, right? You can’t really hear in space, because there’s no air, there’s no stuff, no medium for that information to travel to you through. But there are definitely interesting ways of taking all the information that we do get from the universe, and translating that into some other form. And sound is just, I think, a really useful version of that, that that we haven’t done perhaps as much with as we could.

HOST PADI BOYD: You’ve heard data sonifications on this show before…in our episodes about Landsat and exoplanets. Sonifications are a great way to understand a concept or a data set in a new way.

Kimberly Arcand

I think it’s this idea that we can try new things with our data. And one does not necessarily have to be prioritized over the other. There are other ways of knowing our universe and other ways of exploring the things that are out there.

Kimberly Arcand

There’s this incredible sandbox of NASA data to play with, we have so much other data of the universe, and there’s always a way to explore it in some new dimension, quite literally, sometimes. It’s not until you’re sort of sitting in that sandbox seeing, ‘Am I gonna build a sandcastle today, or just make a little sand angel? What am I going to do with this, this data?’ and it sort of shows you where you need to go. But there’s always something new to learn.

HOST PADI BOYD: NASA scientists use data sonifications to better understand different qualities of the cosmic objects in space photographs. Data from Hubble’s Ultra Deep Field image, released in 2014, was recently translated into one of these data sonifications.

[Hubble Ultra Deep Field Sonification Long Version by SYSTEM Sounds (M. Russo, A. Santaguida)]

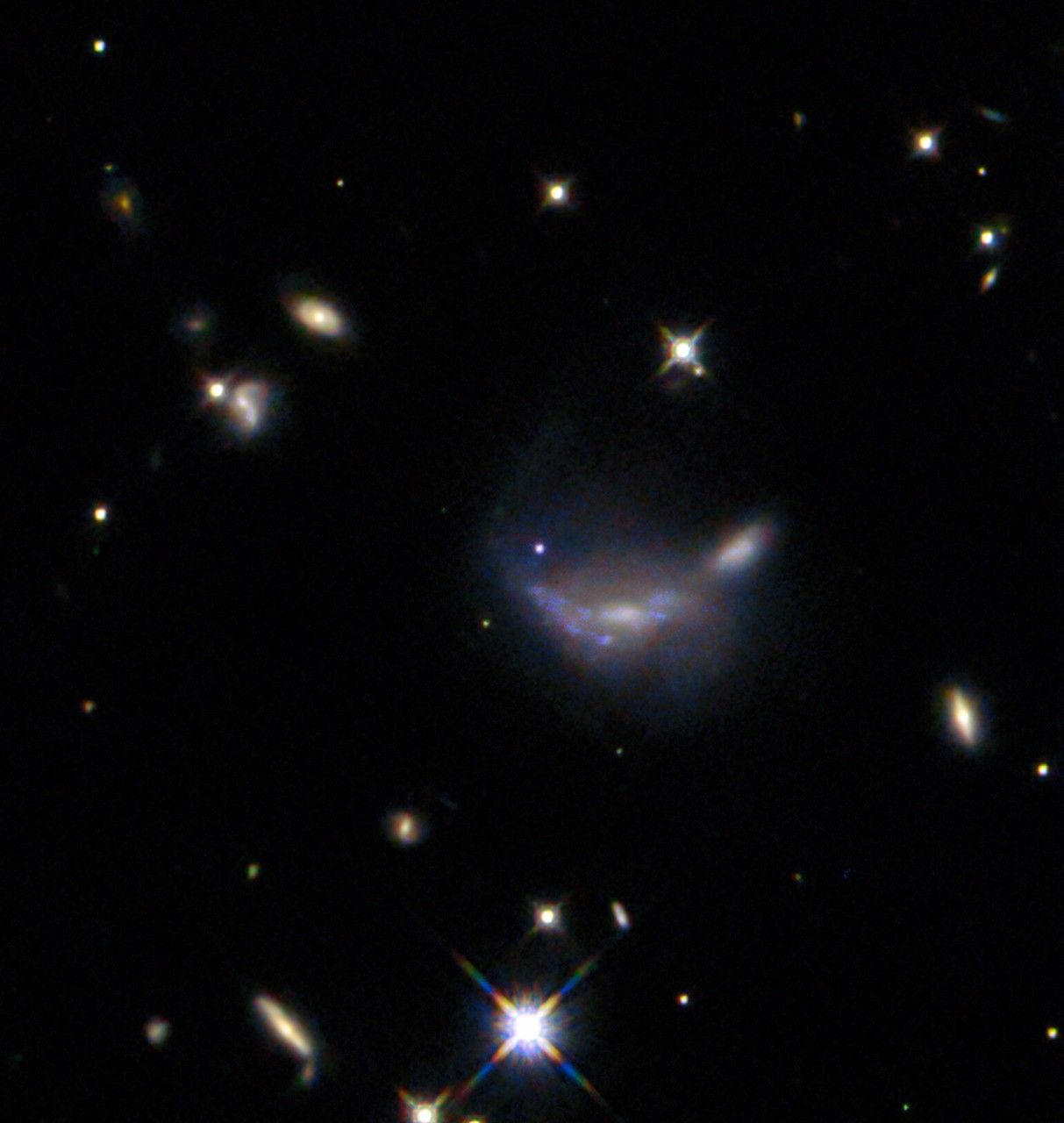

HOST PADI BOYD: Hubble’s first deep field observations were taken in 1995 and changed our understanding of astronomy. It was a landmark project, showing the world a glimpse of just how big our universe really is.

HOST PADI BOYD: Ken Carpenter has worked with the Hubble mission for decades now, and remembers the story behind the original deep field image.

Ken Carpenter

The basic concept was to find a spot in the sky that appeared to us in existing data to be as blank as possible. Now at first, that sounds, like, insane, and members of the astronomical community were not afraid to tell us this. But the idea was, and it was actually very reasonable, was to not have anything in the foreground. So you could look as far into space as possible.

Ken Carpenter

So we found a spot, it was about a fifth of the size of the full moon, so a pretty small spot in the sky that had almost nothing in it.

HOST PADI BOYD:The original Deep Field image was made by taking exposures over a 10 day period.

Ken Carpenter

… And then as time went on, the original Deep Field was mostly in visible light. Then we made an enhanced deep field where we added infrared light after we got a new camera onboard telescope that was really good. And then we made what was called the Ultra Deep Field.

Ken Carpenter

That was 841 images total stacked together. So you can see we’re talking about co-adding, stacking things, that’s a lot of images. The resulting image of this area that appeared to be totally blank on the sky had at least 10,000 individual galaxies. And this image is spectacular because even the small points of light on it are actually galaxies, not stars. There’s a few stars in the field, very few. So you have 10,000 galaxies, each one has 100, 200, 300 billion stars. You multiply those together and you’re really starting to get some very large numbers. And then remember, you’ve only got a tiny area, the sky. So if you multiply by the remaining area of the sky, you find out, to talk in very general terms, that the number of stars in the universe that we see over the whole sky is more than all the grains of sand on all the beaches of the world. And it was kind of funny, when we first did that, we used that analogy. And then several years later, somebody did a reanalysis of the data and accounted for more subtleties in the observations and said, ‘Oh, you know, actually, we’re a little bit off. It’s actually 10 times more than that.’

HOST PADI BOYD: What you’ve been hearing is a representation of all the galaxies in that ultra deep field photo, played as sound.

[Hubble Ultra Deep Field Sonification 60 second Version by SYSTEM Sounds (M. Russo, A. Santaguida)]

HOST PADI BOYD: We start in the present day, and go backwards in time, hearing a note for each galaxy when it emitted the light captured in the image. The farther away the galaxy is, the longer its light has traveled before reaching the Hubble telescope.

HOST PADI BOYD: In just under a minute, we can hear back nearly 13 billion years to the farthest galaxies in that photo. The light we receive from those galaxies was emitted when the universe was only a few hundred million years old.

HOST PADI BOYD: It sounds beautiful, right? But data sonifications like this one can also be a helpful tool for NASA employees and citizen scientists alike.

HOST PADI BOYD: Denna Lambert works at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center as a project manager. She previously worked as the disability programs manager. With that department, she helped develop initiatives to support NASA’s workforce of individuals with disabilities.

[Chandra Deep Field South Sonification by NASA/CXC/SAO/K.Arcand, SYSTEM Sounds (M. Russo, A. Santaguida]

HOST PADI BOYD: Denna is also blind and experiences a lot of the information from our universe through sound.

Denna Lambert

We are known for our beautiful images that we get back from our satellites. In the area of data sonification, what we find is that while we can see a lot of things with our eyes, we can also interpret a lot of information with our ears. And can gain deeper insights into what we are trying to learn and discover.

HOST PADI BOYD:One of the most impactful parts of the ultra deep field sonification for Denna was understanding the scope of time…and how many billion years it takes for those galaxies to form.

[Supernova 1987A Sonification by NASA/CXC/SAO/K.Arcand, SYSTEM Sounds (M. Russo, A. Santaguida]

Denna Lambert

You know, I have the experience of a 40 year old, we sometimes lose our sense of time. These events happened over thousands and thousands of years. It’s hard to kind of wrap my head around it, but at the same time, it makes sense.

HOST PADI BOYD: We can learn a lot from data when it’s been translated into a new form, like sound or imagery. But we’re also expanding the range of people who have access to work with that data.

Denna Lambert

It’s pretty common knowledge that everyone has a different style of learning. People interpret information differently.

[Bullet Cluster Sonification by NASA/CXC/SAO/K.Arcand, SYSTEM Sounds (M. Russo, A. Santaguida]

Denna Lambert

If we want to provide this information, our science, our findings, to as wide of an audience, we should always keep that in mind. We have people with disabilities, blind individuals, deaf individuals, in all types of positions. Flight directors who are deaf, financial managers who utilize wheelchairs, to electrical engineers who are blind. Data and information and science should be, as much as possible, made available to everyone.

[Data Sonification: Caldwell 73 by SYSTEM Sounds (M. Russo, A. Santaguida]

HOST PADI BOYD: When Denna found a series of braille books about Hubble images, they helped open up the world of astronomy for her.

Denna Lambert

So as an early college student, I came across the “Touch the Universe” books, that provided tactile information on the images from Hubble. So I have access to something that was never available to me in print. But when I was able to hear this online through YouTube, or through a NASA website, I think looking at the, I believe that was the star nursery, that was like, ‘Oh, wow, now I get it. Now I get the full shape and depth of what I’m seeing.’ While we may not visually be able to look up in the sky and see it, we have to use, you know, various filters to see that information, I can actually touch it and hear it. That makes sense for me as a blind person.

[Song: Beautiful Planet Instrumental by Andreas Andreas Bolldén]

HOST PADI BOYD: Science is for everyone. The more methods we have to conceptualize and think about scientific information, and the more people we can invite to contribute ideas, the fuller our understanding becomes.

HOST PADI BOYD: As technology continues, we are able to touch, listen, and look at information about space. We are interpreting our universe every day, and getting closer to a better understanding of our mysterious surroundings.

HOST PADI BOYD: Missions like Chandra and Hubble give us a front-row seat to the cosmos, and as we learn about the information they send back, we also learn how to become more curious about the things around us.

[Outro: Curiosity by SYSTEM Sounds]

HOST PADI BOYD:This is NASA’s Curious Universe. This episode was written and produced by Christina Dana and Elizabeth Tammi. Our executive producer is Katie Atkinson.

HOST PADI BOYD: The Curious Universe team includes Maddie Arnold, Kate Steiner and Micheala Sosby, with support from Emma Edmund, Anisha Engineer, and Priya Mittal.

HOST PADI BOYD: Our theme song was composed by Matt Russo and Andrew Santaguida of System Sounds.

HOST PADI BOYD: Special thanks to Ryland Heagy, Jim Jeletic, Claire Andreoli and the Hubble Space Telescope team.

HOST PADI BOYD:If you have a question about our universe, you can email a voice recording or send a written note to NASA-CuriousUniverse@mail.NASA.gov. Go to nasa.gov/curiousuniverse for more information.

HOST PADI BOYD: If you liked this episode, please let us know by leaving us a review, tweeting about the show @NASA, and sharing with a friend.

BONUS SCENE

Denna Lambert

I was a little girl in Arkansas, had not met an astronaut. No one in my family was an engineer or a scientist. When someone asked “Hey, I see that you have this this interest and you have this desire, why not become an engineer or why not become a scientist and be a part of that?” Now it was a long road to get to NASA, but I think if you can dream it I don’t know if the right phrase is if you dream it you can be it. Do not limit yourself when it comes to either choosing a career field or even accessing information, that it is, it is available for everyone.