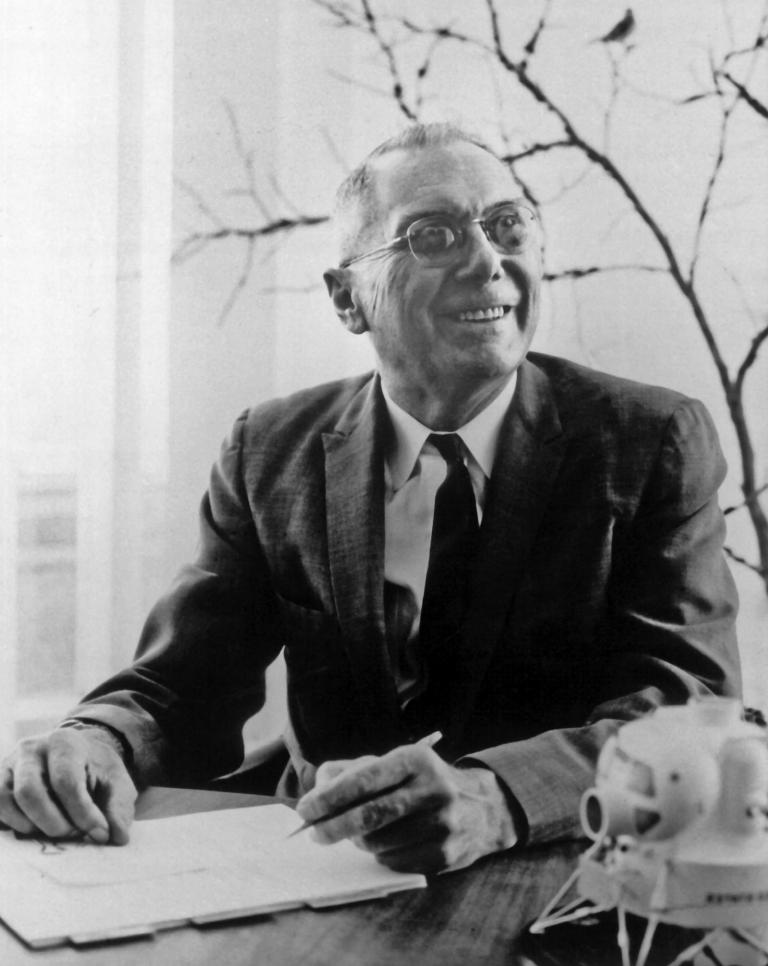

Dr. Hugh L. Dryden

NASA Deputy Administrator

In 1949, Dr. Hugh L. Dryden become the first person to hold the new position of director of the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA). He continued in that position until October 1, 1958, when the NACA became the nucleus of the new National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), and Dryden was appointed its first deputy administrator, a position he held until 1965 when he died from cancer on December 2.

Dryden played a critical role in nurturing flight research that has largely defined NASA’s Armstrong Flight Research Center. The center was named in his honor in 1976, and then was subsequently renamed in honor of Neil Armstrong in 2014, at which time, the Western Aeronautical Test Range was renamed the Dryden Aeronautical Test Range.

During the early 1960s, Dryden became NASA’s revered elder statesman of science and shared with the administrator the management of a multi-billion-dollar program to develop space vehicles, advance space-related sciences, enable humans to travel out to the moon and back, and carry out extensive aeronautical research.

Dryden also served as chief U.S. negotiator for early historic agreements with the Soviet Union on the peaceful use of space.

Dryden was a child prodigy. Born July 2, 1898, in the tiny town of Pocomoke City, Maryland, he often boasted, “The airplane and I grew up together.” His early thoughts on aeronautics ran deep. Dryden was 12 years old when he saw an aircraft for the first time. It was an Antoinette, a 40-mph monoplane with a 50-horsepower engine. He wasn’t impressed with its performance. A few days later he wrote an essay for his English class at school, titled “The Advantages of an Airship Over an Aeroplane,” in which he compared the greater passenger and cargo payloads an airship has over winged machines for commerce, exploration, and recreation. His teacher thought the paper was “illogical” and graded it with an “F.” But that didn’t stop his thinking.

At the age of 14 he entered Johns Hopkins University, graduated with honors three years later, and earned a master’s degree in 1918. His thesis was “Airplanes: An Introduction to the Physical Principles Embodied in Their Use.” By this time, Dryden had attracted the attention of Dr. Joseph S. Ames, who headed the university’s Department of Physics and recommended Dryden for a staff job at the National Bureau of Standards. Ames called Dryden “the brightest young man … without exception” he had ever worked with.

Dryden soon was working in the bureau’s newly created wind tunnel section, while also completing his doctoral requirements. His thesis this time was “Air Forces on Circular Cylinders,” describing drag and air flow over the engine. The research marked the beginning of a career devoted to the study of turbulence and boundary layer problems.

In 1920, Dryden was named to head the bureau’s aerodynamics section, where he studied air pressures on everything from fan and propeller blades to buildings. Some of his work in the mid-1920s investigated airfoil characteristics at air speeds at and just beyond the speed of sound. This was at a time when the fastest aircraft were flying at less than 300 mph. His work led to the design of low-turbulence wind tunnels, and his data – used by the NACA – contributed to development of the laminar flow wings used on the famed P-51 Mustang fighter of World War II.

Dryden, who became a member of the NACA in 1931, saw much of his work at the bureau switched to defense work as World War II loomed in the late 1930s. In 1940, he was named to head the fledgling guided missile section of the Office of Scientific Research and Development (OSRD). One of OSRD’s products was the “Bat,” the only American guided missile used in combat during the war, which was credited with sinking several enemy vessels. His work earned him the Presidential Certificate of Merit and led to his move into management, where he participated in the framing of policies dealing with future research and development.

In 1946, Dryden became assistant director of the bureau, followed in six months by his appointment as associate director. Within another six months, he was selected to succeed Dr. George W. Lewis as the NACA’s director of Aeronautical Research, and by 1949 he had become director of the NACA. At the time, the NACA had about 6,000 personnel in major facilities at the Ames, Lewis, and Langley research laboratories, at Wallops Island in Virginia, and at what was then the High-Speed Flight Research Station at Muroc, California (now NASA Armstrong).

Dryden helped shape policy that led to development of the high-speed research program and its record-setting X-15 rocket aircraft. His leadership was evident in establishing vertical- and short-takeoff-and-landing aircraft programs, and he sought solutions to the problem of atmospheric re-entry for piloted spacecraft and ballistic missiles. Dryden was also instrumental in the development of the Unitary Wind Tunnel Plan, which saved millions of dollars by avoiding facility duplication.