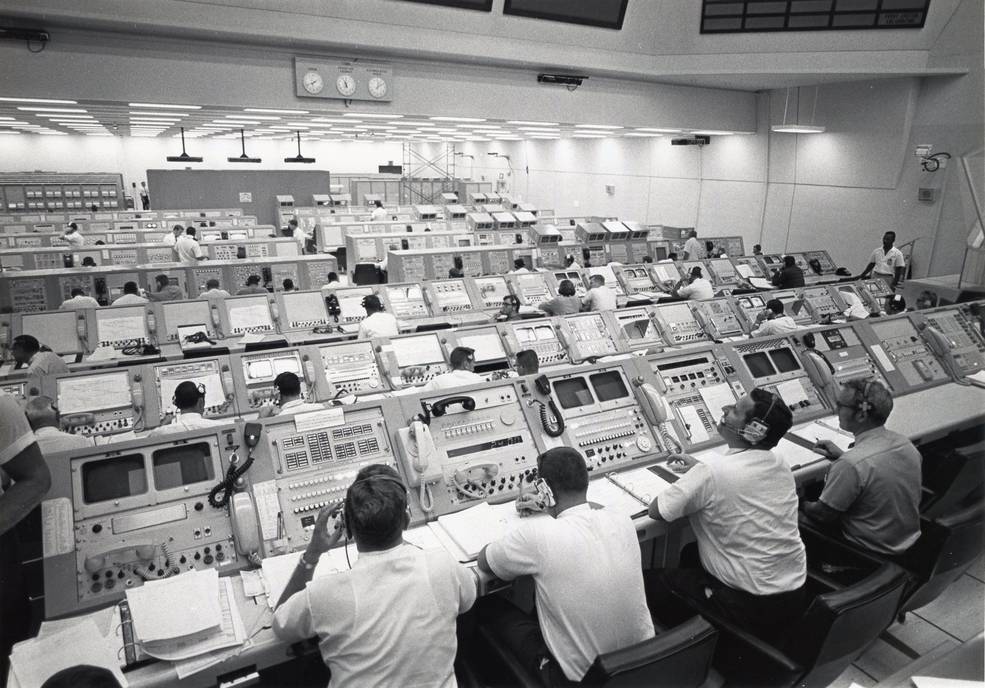

As the Apollo 11 mission lifted off on the Saturn V rocket, propelling humanity to the surface of the Moon for the very first time, members of the launch firing team inside Launch Control Center watched through a window.

The room was crowded with men in white shirts and dark ties, watching attentively as the rocket thrust into the sky. But among them sat one woman, seated to the left of center in the third row in the image below. In fact, this was the only woman in the launch firing room for the Apollo 11 liftoff.

This is JoAnn Morgan, the instrumentation controller for Apollo 11.

Today, this is what Morgan is most known for. But her career at NASA spanned over 45 years, and she continued to break ceiling after ceiling for women involved with the space program. In addition to being the first woman at NASA to win a Sloan Fellowship, she was the first woman division chief, the first woman senior executive at Kennedy Space Center (KSC), the first woman associate director for KSC, the first woman director of Safety and Mission Assurance…and the list goes on, as this feature will show.

So, let’s begin to answer a question that has become crucial to understanding women’s contributions to the Moon landing and NASA at large: Who is JoAnn Morgan?

“A precocious little kid”

As a child, Morgan was a self-described “precocious little kid.” She loved math, science and especially music — so much so, that she was convinced she would grow up to become a piano teacher. But that trajectory quickly changed after her father uprooted the entire family from their close-knit community in Alabama, and moved everybody to Titusville, Florida.

The move was jarring for the whole family. Morgan, a high school junior, was plucked out of a school she had been attending since the third grade and felt as if she had been “plopped down” somewhere completely new.

Morgan noticed many differences between her new Florida home and where she had come from. The main one? Rockets.

Rockets blasted off just across the river from her high school so often, that watching them with her friends felt just like “watching fireworks on the beach.” But to say they were the main inspiration for Morgan’s eventual career at NASA? That would be way off the mark. If anything, the rocket launches were just background noise. They were little more than flashes of light in the peripheral.

“The opportunity for new knowledge”

Those rockets began to mean something much more to Morgan on Jan. 31, 1958, the day Explorer 1 was launched into space — the first satellite to do so from the United States. Satellites were not as ubiquitous as they are today. At this point in history, the Soviet Union’s Sputnik and Sputnik 2 were the only two satellites successfully launched into orbit.

Explorer 1 was instrumental in discovering what has become known as the Van Allen radiation belt. The Explorer 1 instrumentation reacted to what appeared to be radiation, and thus Dr. James Van Allen theorized that charged particles were trapped in space by Earth’s magnetic field.

This was the discovery that inspired Morgan to be a part of the space program. The roaring of the nearby rocket launches was nothing compared to this.

“I thought to myself, this is profound knowledge that concerns everyone on our planet,” she says. “This is an important discovery, and I want to be a part of this team. I was compelled to do it because of the new knowledge, the opportunity for new knowledge.”

The opportunity came when Morgan spotted an advertisement for two open positions with the Army Ballistic Missile Agency. The ad listed two Engineer’s Aide positions available for two students over the summer.

“Thank God it said ‘students’ and not ‘boys’” says Morgan, “otherwise I wouldn’t have applied.”

“I’ve got rocket fuel in my blood”

With Morgan’s strengths in math and science, it was no wonder when she got the internship. From there, things moved pretty quickly: “Graduation from high school was on the weekend, and I went to work for the Army on Monday. I worked on my first launch on Friday night.”

At age 17, Morgan began work during the summers as a University of Florida trainee for the Army at Cape Canaveral Air Force Station. This program was quickly rolled into a brand-new space exploration agency that had just been forged in response to early Soviet achievements: a little agency called the National Aeronautics and Space Administration, also known as NASA.

As Morgan worked in the summers for the new NASA, and during the school year chipped away at a Bachelor of Arts in mathematics from Jacksonville State University, her potential did not go unnoticed. Dr. Wernher von Braun, chief architect of the Saturn V rocket that propelled Apollo spacecraft to the Moon, and members of his team recognized the level at which Morgan could contribute to the human spaceflight program.

“All of my mentors were men,” says Morgan. “That’s just a plain fact and that needs to be acknowledged.”

Dr. Kurt Debus, the first director of KSC, looked at Morgan’s coursework and saw that she had experience writing technical papers, working with data systems and building computer components (which were also not as ubiquitous as they are today.) He provided Morgan with a pathway to certification, and a couple of courses later, she was certified as a Measurement and Instrumentation Engineer and a Data Systems Engineer, and was employed as a Junior Engineer on their team.

“It was just meant to be for me to be in the launching business,” she says. “I’ve got rocket fuel in my blood.”

And from all appearances, that was the perfect summation. Morgan was a talented mathematician, a fantastic communicator and a bona fide engineer — but that didn’t stop prejudice, especially in the sixties.

“You don’t ask an engineer to make coffee”

Morgan heard later from colleagues that when she was hired to join the team, her immediate supervisor, Jim White, called everyone for a meeting — except her. As the room filled with men, White explained to the crew:

“This is a young lady who wants to be an engineer. You’re to treat her like an engineer. But she’s not your buddy. You call her Ms. Hardin. You’re not to be familiar.”

“Well, can we ask her to make coffee?” someone asked.

“No,” White said. “You don’t ask an engineer to make coffee.”

White wanted to make it perfectly clear to the team: Morgan was a serious engineer, and her being a woman did nothing to affect that. By speaking candidly with the team, White intended to establish an environment of respect for Morgan. However, this was not always how it played out.

“JoAnn, you are welcome here”

There was a seemingly infinite amount of obstacles that Morgan was forced to overcome — everything from obscene phone calls at her station to needing a security guard to clear out the men’s only restroom.

“You have to realize that everywhere I went — if I went to a procedure review, if I went to a post-test critique, almost every single part of my daily work — I’d be the only woman in the room,” reflects Morgan. “I had a sense of loneliness in a way, but on the other side of that coin, I wanted to do the best job I could.”

“A startling moment” for Morgan came when a test supervisor saw her sitting down at Blockhouse 34 to plug in her headset to acquire test results.

“The supervisor came and just whacked me over the back — actually hit me in the back! He said ‘we don’t have women in here!’ He had this ugly look on his face and I thought, uh-oh.”

Morgan called Karl Sendler, the man who developed the launch processing systems for the Apollo program and had ordered the test results, and said, “Uh…this test supervisor said women aren’t allowed here.”

He replied: “Oh, don’t listen to him! Plug in your headset and get those test results to me as soon as you can.”

In response to the test supervisor’s treatment of Morgan, others came forward to make it known that she was accepted. Rocco Petrone, who presided over the development of the Saturn 5 lunar launch vehicle and operation, later tapped Morgan on the shoulder.

“JoAnn, you are welcome here,” he said.

“You are our best communicator”

In spite of working for all of the Mercury, Gemini and Apollo programs, and being promoted to a senior engineer, Morgan was still not permitted in the firing room at liftoff — until Apollo 11, when “Karl Sendler went to bat for me.”

Without her realizing, Sendler had had to go all the way to the top to ask permission from Debus. When Sendler called Morgan into his office to share the good news, he was “practically gleeful”:

“You are our best communicator,” he said. “You’re going to be on the console for Apollo 11!”

The added bonus was the fact that Morgan wouldn’t have to work the night shift, 3pm to 3am. For the first time, she would get off work at 3 in the afternoon and spend time with her husband who, as a schoolteacher and bandmaster, she rarely got to see. As soon as the launch was over, he would whisk her off to Captiva Island on a boat trip to celebrate.

“I was just thrilled,” she says. “My life was coming together. I would get to be there for the launch, feel the shockwave hit, and then — I got to go on vacation!”

“It absolutely made my career”

To be the instrumentation controller in the launch room for the Apollo 11 liftoff was as huge as a deal as it sounds. The launch is the beginning of the mission, and after the first couple of critical events the launch team is devoted to — including launch and translunar injection — Mission Control team in Texas would take over and the launch team would have zero control.

For Morgan, to be there at that pivotal point in history was ground-breaking: “It was very validating. It absolutely made my career.”

Perhaps the best part was finally being able to feel the vibrations of the shockwave. Up until then, Morgan had always been at a telemetry station or a display room or an upper antennae site for launch, and would have to hear from other people about what the vibrations felt like. Now, Morgan finally had the chance to experience them for herself.

“There’s a whole wealth of knowledge NASA can achieve”

Much like the Saturn V rocket, Morgan’s career took off. She was the first NASA woman to win a Sloan Fellowship, which she used to earn a Master of Science degree in management from Stanford University in California.

When she returned to NASA, she became a divisions chief of the Computer Systems division. This was in the seventies, when the agency was transitioning from using old, giant computers to many smaller computers. The change was supplemented with the fact that she was the first woman to have that role: “So, people were having to change and adapt to me and the new technology. So that was a lot to choke on for some people! A double whammy!”

It was difficult, but Morgan once again proved she was capable. She was “the manager with the velvet glove.” She combined her Southerner, gentlewoman personality with her training at Stanford to inspire change and move people down the road.

From there, Morgan excelled in many other roles, including deputy of Expendable Launch Vehicles, director of Payload Projects Management and director of Safety and Mission Assurance. She was one of the last two people who verified the space shuttle was ready to launch and the first woman at KSC to serve in an executive position, associate director of the center.

But what excited Morgan the most about her contributions was the same thing that inspired her to join the space program in the first place: the scientific discoveries.

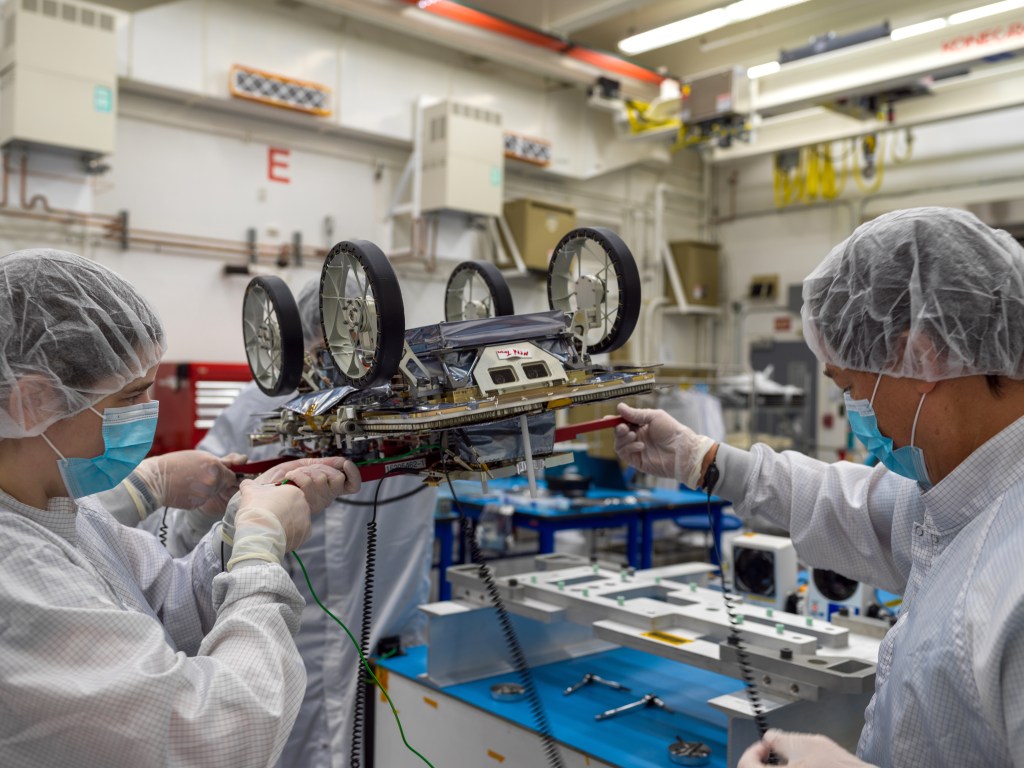

“My last mission was those two little plucky Mars rovers, [Spirit and Opportunity]. That was a lot of fun — getting people to understand there’s a whole future out there, there’s a whole wealth of knowledge NASA can achieve.”

To this day, Morgan is still one of the most decorated women at KSC. Her numerous awards and recognitions include an achievement award for her work during the activation of Apollo Launch Complex 39, four exceptional service medals and two outstanding leadership medals. She also received the Kurt H. Debus Award, as well as two meritorious executive awards from President Bill Clinton. In 1995, she was inducted into the Florida Women’s Hall of Fame.

After serving as the director of External Relations and Business Development, she retired from NASA in August 2003.

“I hope that photos like the ones I’m in don’t exist anymore.”

Florida Governor Jeb Bush appointed Morgan to be a state university trustee. She had already worked on boards at the University of Florida’s Aerospace Engineering, University of Central Florida’s College of Engineering and the University of West Florida’s Institute for Human and Machine Cognition (IHMC).

While serving as a trustee, Morgan realized how important it was to encourage more women to pursue careers and college programs in STEM. Today, she sponsors endowments and scholarships at seven universities and provides internships at IHMC.

“Even though I’m almost 80 years old, I’m not giving up,” she says.

Morgan encourages young people to stick with STEM careers even when they are hard work, because the rewards will be worth it in the end.

“There is such a great variety of work to do within the NASA family: government, contractors, university partnerships — there will be a place for you to fit in,” says Morgan. “I had fun. I had wonderful people to work with. You’re just not going to have a dull day.”

Morgan is especially excited about seeing more women involved with the upcoming Artemis missions to return humans to the Moon and eventually make it to Mars. She remembers clearly when Dr. von Braun described to her in person about the goal to go to Mars — although, he had calculated that we would have already made it there by now.

“So, we’re behind, by JoAnn Morgan time.”

People today are reflecting on the 50th anniversary of Apollo 11, looking back on photos of the only woman in the launch firing room and remembering Morgan as an emblem of inspiration for women in STEM. However, Morgan’s takeaway message is to not look at those photos in admiration, but in determination to see those photos “depart from our culture.”

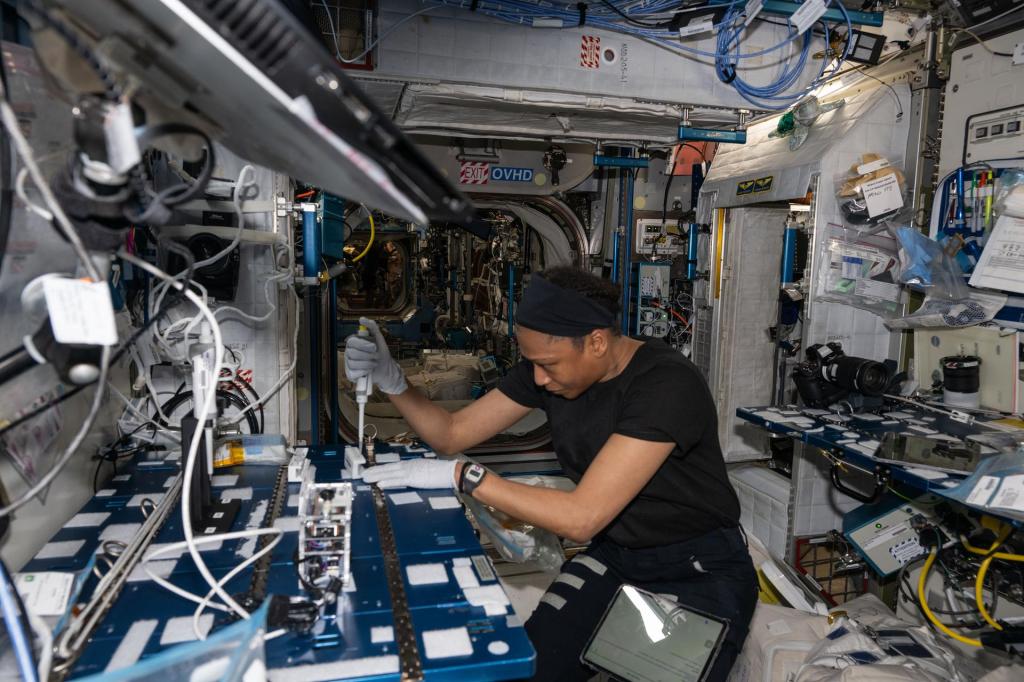

“I look at that picture of the firing room where I’m the only woman. And I hope all the pictures now that show people working on the missions to the Moon and onto Mars, in rooms like Mission Control or Launch Control or wherever — that there will always be several women. I hope that photos like the ones I’m in don’t exist anymore.”

by Thalia Patrinos

NASA Headquarters