Growing up with “blowing snow days” in a town above the Polar Circle, physical scientist Alexander Marshak now studies blowing snow, clouds and aerosols through satellite images.

Name: Alexander Marshak

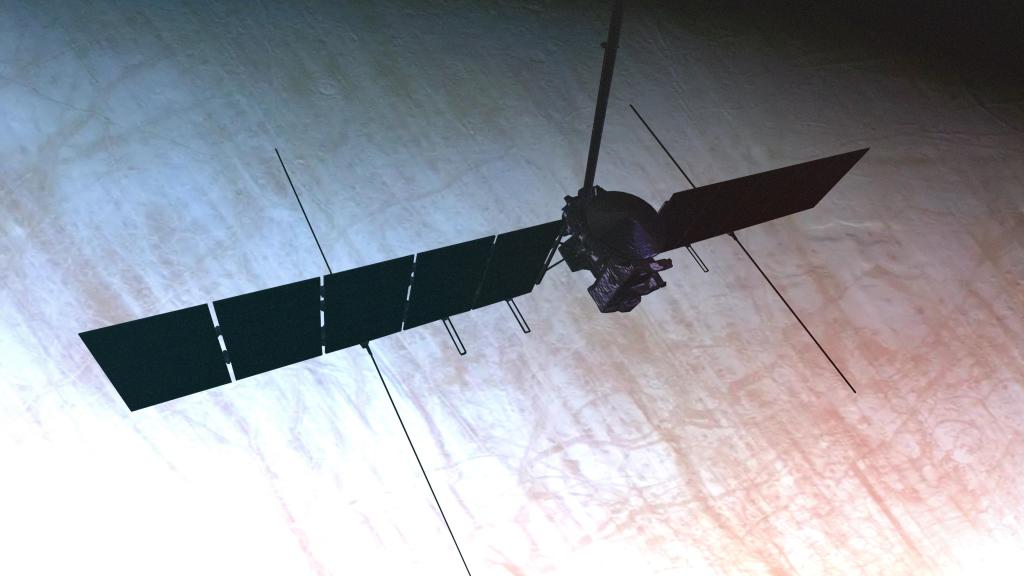

Title: Deputy Project Scientist for the Deep Space Climate Observatory

Formal Job Classification: Physical Scientist

Organization: Code 613, Climate and Radiation Laboratory, Atmospheric Sciences Directorate

What do you do and what is most interesting about your role here at Goddard? How do you help support Goddard’s mission?

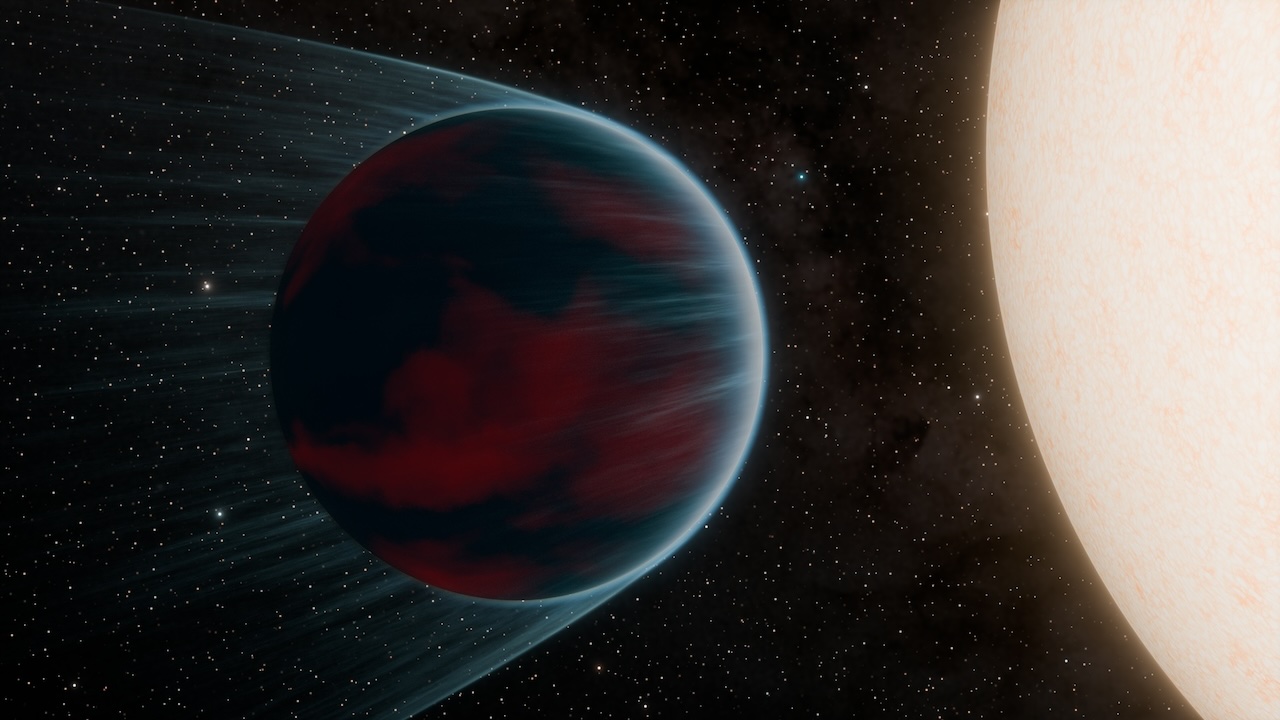

I am an atmospheric scientist. I study clouds, aerosols and blowing snow. Clouds and aerosols continue to be the largest contributors to uncertainties in estimating or interpreting the Earth’s radiation budget, which is the amount of energy that the Earth gets from the Sun and radiates back to space. Interpreting aerosol cloud interactions is a big challenge.

Recently, I became involved in studying a boundary between cloudy and clear skies. We call this boundary the transition zone. It was thought that the boundaries were well-established and can be easily determined where clouds end and the clear sky starts. We discovered that there is a big transition zone where aerosol particles humidify and swell while the cloud droplets evaporate and shrink. The area represented by a transition zone complicates estimates of aerosols effects on climate and must be directly confronted to solve the aerosol-climate problem.

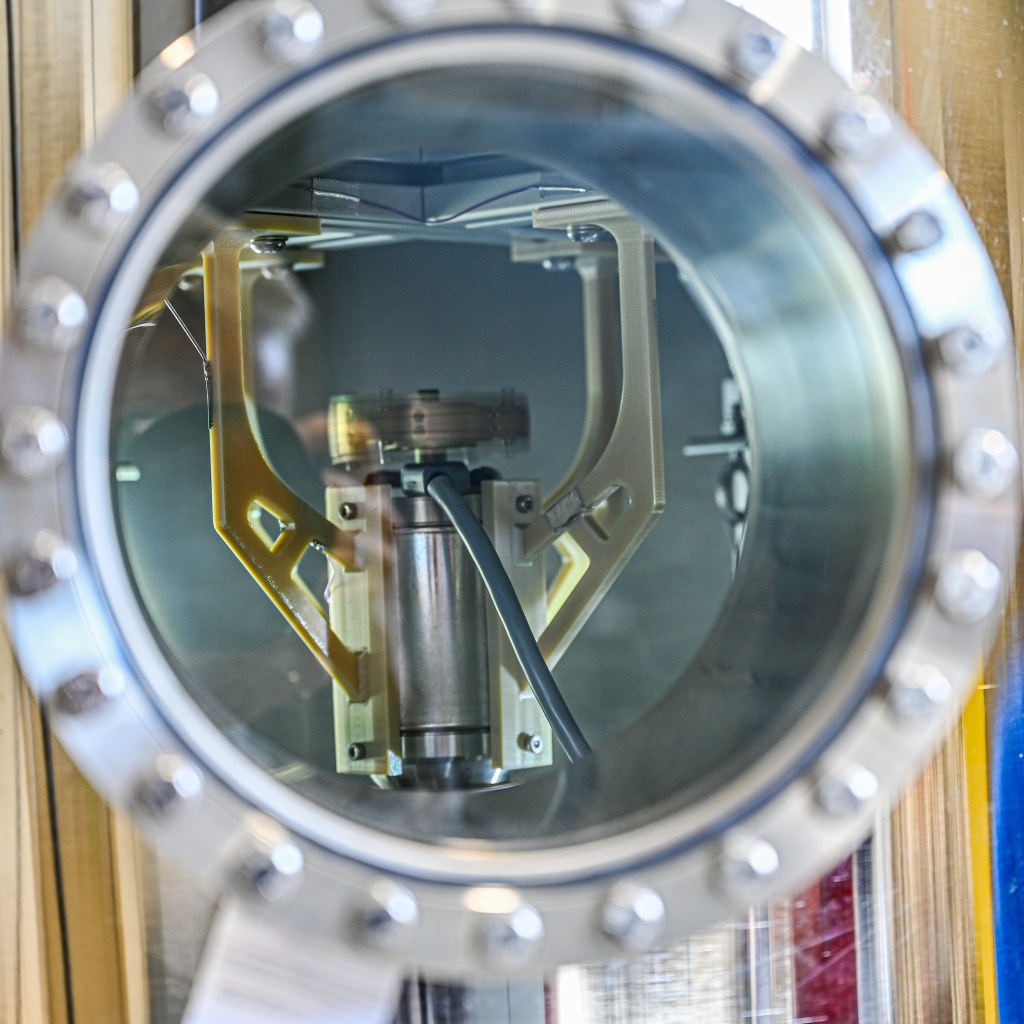

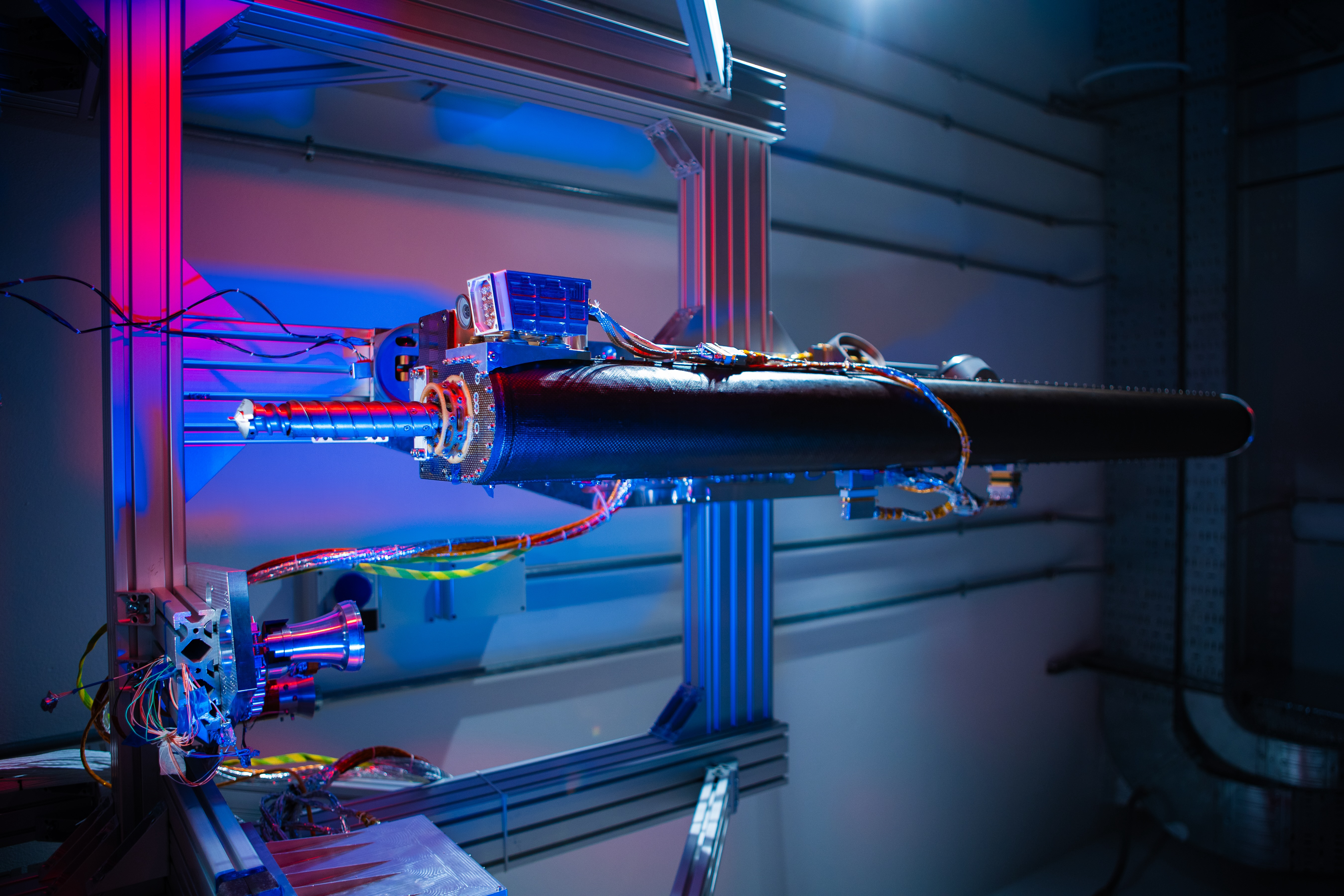

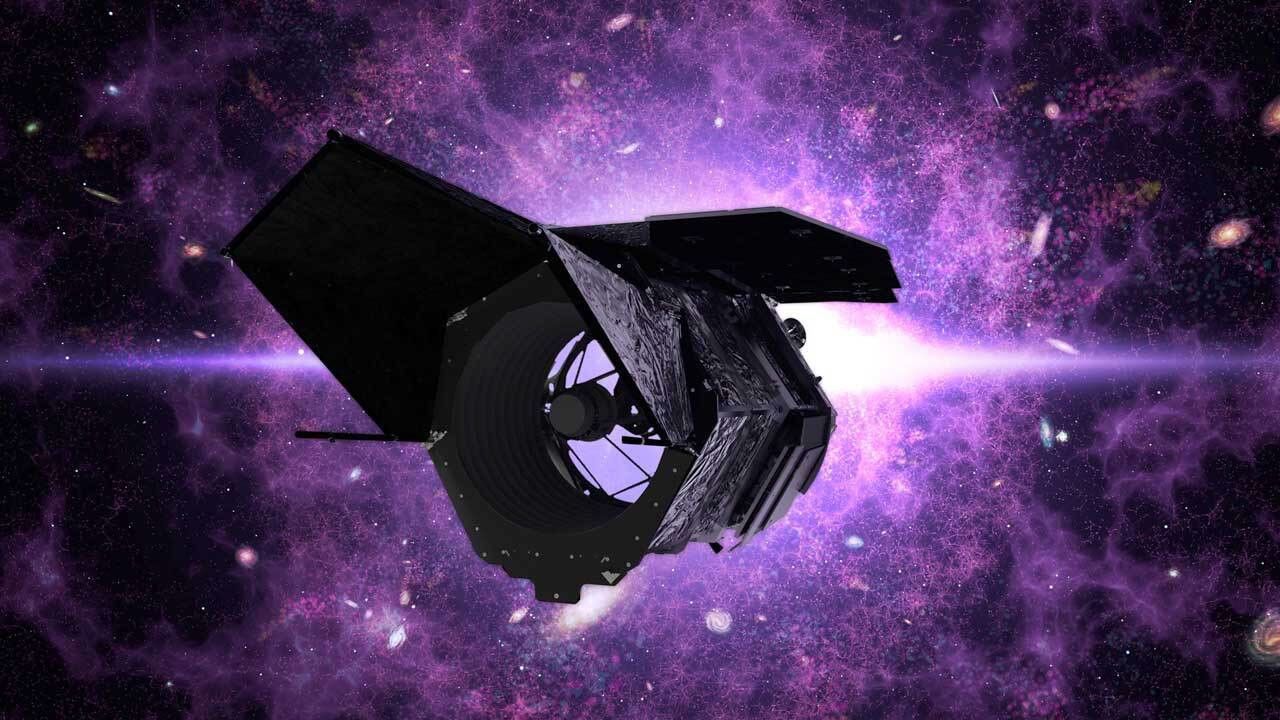

I am also the Deputy Project Scientist for the Deep Space Climate Observatory (DSCOVR) which will be launched in January 2015. DSCOVR will fly one million miles away from the Earth towards the Sun to the point of equal gravitational force between the two. Our primary objective is to provide early warning about approaching solar storms; this is important to avoid disruption to our power supply, GPS, cell phones, etc. Our secondary objective is to look at the part of the Earth illuminated by the Sun to obtain information about ozone, aerosols, clouds and vegetation. Being so far away from the Earth, DSCOVR will be able to see the entire Earth from sunrise to sunset.

Where do you work?

I am a theoretician. I mostly work sitting in my office behind my computer. I work with data and models.

Where did you grow up?

I grew up in the very north of Russia in Severomorsk on the Barents Sea near Murmansk. The city is located above the Polar Circle. I spent my free hours cross-country skiing and playing chess. During the long winters I often saw the magnificent Northern Lights.

Where were you educated?

I attended Tartu University in Estonia. There I got a master degree in applied mathematics. A few years later, I received my PhD from the University of Novosibirsk in numerical analysis, which involves solving mathematical problems numerically. My thesis was about the mathematical problems of radiation transfer, a field that combines atmospheric physics, astrophysics, radiative processes in vegetation and nuclear physics. As a mathematician, this was a fascinating problem to study.

I then returned to Estonia to work at the Institute of Astrophysics and Atmospheric Physics near Tartu. I studied radiative processes in vegetation, which involves measuring how much solar energy from the Sun is absorbed by vegetation.

After that, I attended the Institute of Bioclimatology at Goettingen University in Goettingen, Germany as an Alexander Von Humboldt Fellow, one of the most prestigious fellowships in the world. There I continued my research in radiative processes in vegetation.

To prepare for life in Germany, before starting my fellowship, I took two months of intensive German language classes at the Goete Institute in Goettingen. I spoke mostly English at the University and used German everywhere else.

From above the Polar Circle to Goddard is a long way. How did you come to Goddard?

In 1991, I happened to see an advertisement for a postdoctoral position in atmospheric science at the Climate and Radiation Branch of the Laboratory for Atmospheres at NASA Goddard. The position was for someone to study radiative transfer in clouds. I applied. In my cover letter, I said that working at Goddard would be a scientist’s dream come true. I got the job and still believe it is a dream come true. I started working at Goddard at the end of August 1991. I first began as a contractor and a University researcher and then became a civil servant.

I was probably the last Soviet citizen hired as a Goddard contractor. My passport was issued by the Soviet Union. However, the USSR collapsed in August 1991, just at the time when I arrived at Goddard to start working.

My wife and two daughters came with me too. My wife now works as a scientific programmer at Goddard and my daughters have moved to Boston and Seattle. My eldest daughter has recently received her doctoral degree while the youngest has just started a PhD program in Boston.

Who was your mentor at Goddard?

For many years I have been working with Warren Wiscombe, an atmospheric scientist who studied clouds. He taught me about radiation transfer in clouds and atmosphere. He is a great scientist, a great man and a great character. I read his papers while I was still in the Soviet Union. He was first my boss and then became a colleague and a friend. I learned a lot about America from Warren. He even introduced me to pumpkin pie, which I have since grown to enjoy very much.

Are you a mentor now?

Yes. Unconsciously, I find myself acting with my mentees the same way that my mentor did with me. Most importantly, he gave me a lot of freedom and I try to do the same with mine.

I tell my mentees that you have to love what you are doing. Science is not only fun, it also requires some necessary routine work. Once you generate ideas, you have to find a way to test them. Frequently your ideas do not lead anywhere. It’s a hard, long road to validate your hypothesis.

What are some of the differences between living in the former Soviet Union and living in America?

In Russia, we have no equivalent to the American phrase “take it easy.” My generation was not taught how to recover from losing. We were expected to win all the time. For example, if you applied for a job, you were expected to get the job. If you wrote a proposal, your proposal was expected to be selected. So, if these things did not turn out as expected, I did not know how to recover quickly.

I was lucky that I got a job here. But when my first proposal was declined, it was very personal and painful to me.

Later, with my mentor’s help, I learned how to analyze and learn from these kinds of situations. I still don’t really “take it easy,” but I’m getting better at it.

As someone who grew up above the Arctic Circle, do you enjoy snow?

Yes, I do very much. Where I grew up, we didn’t have snow days because we had snow from October to April, but we did have “blowing snow days.” These were days when the wind was blowing so hard that we couldn’t open the front door and could hardly see beyond a few yards.

Here in Maryland, children enjoy snow days when schools are closed. In contrast, we didn’t like blowing snow days. Now I feel that I have settled my score with blowing snow because I can detect it and study it using satellites.

Do you have a favorite Russian food?

My specialty is cold borscht, which is excellent in the summer. You take one jar of pickled beets; add some ham, two eggs, two potatoes, a cup of buttermilk, one cucumber and a bunch of chives. The liquid from the pickled beets spices up the dish. This serves two people.

Who is your favorite author?

I love O. Henry’s stories. I initially read them in Russian. I even memorized many of them. Now I also enjoy reading them in English. I like his expressive language and his heroes. One of my favorite stories is “The Last Leaf.”

Check out Alexander Marshak’s Maniac Lecture: https://earth.gsfc.nasa.gov/maniac/marshak

By Elizabeth M. Jarrell

NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, Md.

Conversations With Goddard is a collection of Q&A profiles highlighting the breadth and depth of NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center’s talented and diverse workforce. The Conversations have been published twice a month on average since May 2011. Read past editions on Goddard’s “Our People” webpage.