For the first time in NASA’s history, women are in charge of three out of four science divisions at the agency. The Earth Science, Heliophysics and Planetary Science divisions now all have women at the helm. Each hails from a different country and brings unique expertise to NASA’s exploration efforts.

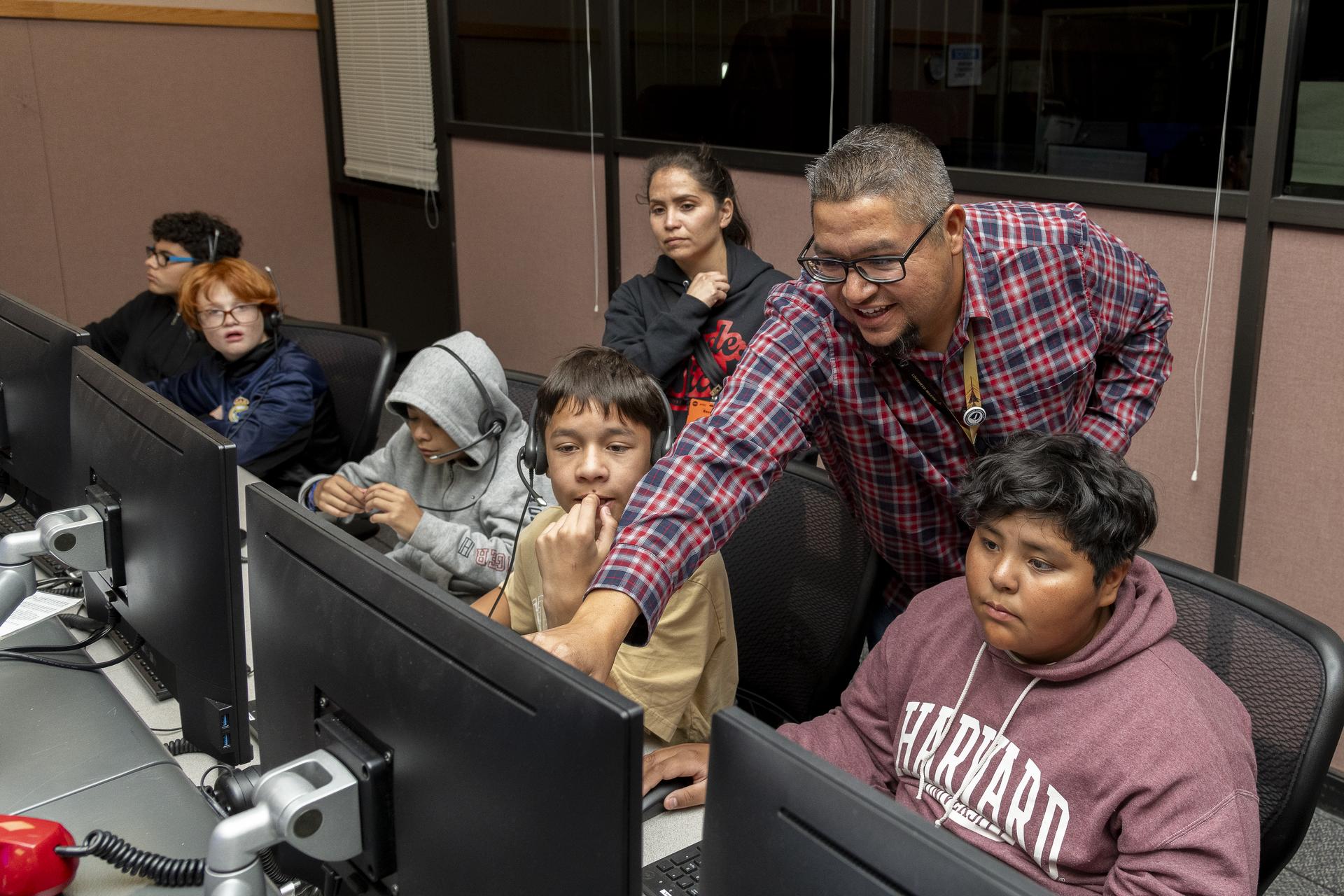

“We have an extraordinary group of women responsible for the success of dozens of NASA space missions and research programs, revealing new insights about our planet, Sun and solar system,” said Thomas Zurbuchen, associate administrator of NASA’s Science Mission Directorate at NASA Headquarters. “They are inspiring the next generation of women to become leaders in space exploration as we move forward to put the first woman on the Moon.”

Sandra Cauffman, acting director of the Earth Science division, leads the agency’s efforts to understand the intricacies of our home planet – the only one where we know life can survive. Her journey to NASA has been one full of determination and persistence.

As a child in Costa Rica, Cauffman loved reading science fiction books such as Jules Verne’s “From the Earth to the Moon” and Isaac Asimov’s novels. Her mother, whom Cauffman considers her hero and inspiration, constantly struggled to make ends meet for her children, but maintained an upbeat attitude.

“Even when we didn’t have anything, even when we got kicked out of places, even when we ended up living in an office because we had no place to go, she was always positive,” Cauffman said. Her mother told her: “You can do anything that you want, you just have to put your mind to it.”

Because the family had no television, they went to a neighbor’s house to watch the Apollo 11 landing in 1969. “I just remember telling Mom I wanted to go to the Moon,” Cauffman said.

Fascinated by physics in high school, Cauffman wanted to continue her studies in college. She worked in a hardware store to help pay for her undergraduate education in physics and electrical engineering at George Mason University in Fairfax, Virginia. As a native Spanish speaker, she struggled daily with English – first learning words like “hammer,” “nail” and “bolt” through her job at the shop. She barely passed her test of English as a second language. But she kept going, eventually earning a master’s in electrical engineering.

She joined NASA in February 1991 as the Ground Systems Manager for the Satellite Servicing Project at Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland. She worked on Hubble’s first servicing mission, the Upper Atmosphere Research Satellite (UARS), the Explorer Platform/Extreme Ultraviolet Explorer (EUVE) and others. She also contributed to the weather satellite program Geostationary Operational Environmental Satellite (GOES) I/M, N/P and R Series, as well as the Mars Atmosphere and Volatile Evolution (MAVEN) mission. After 25 years at Goddard, she moved to NASA Headquarters in 2016, and became deputy director for the Earth Science Division in the Science Mission Directorate. In February 2019, upon the retirement of Michael Freilich, she was named Acting Director of the Earth Science Division.

In her early NASA career, she was often the only woman or one of very few in the room, and developed the courage to speak up for herself. These days, with many more women contributing to NASA, Cauffman looks for opportunities to make sure everyone’s voice is heard. If a young female colleague’s opinion is being overstepped in a meeting, Cauffman will intervene: “Hey, she spoke, can we listen to what she has to say?”

Though she had a brief foray into Mars missions, Earth is Cauffman’s favorite planet. And she enjoys knowing that Earth science has real benefits to society.

“What we do in observing Earth as a system gives us the additional benefit of helping humans here on Earth survive hurricanes, tornadoes, pollution, fires, and help public health,” she said. “Understanding the oceans, the algae blooms — all of those things help humans right here on Earth.”

Her message to young people who aspire to a career like hers reflects her mother’s message to her: “Don’t give up at the first ‘no.’ With determination and perseverance, we can become what we dream we can become.”

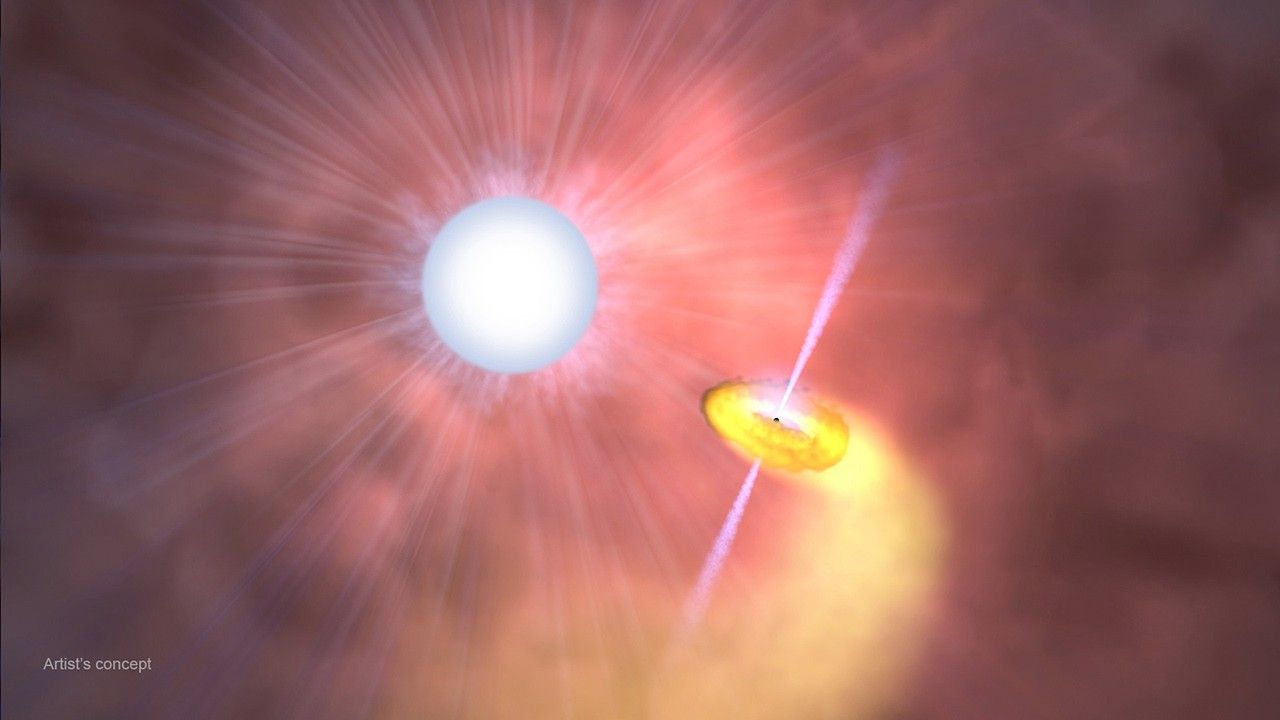

Nicola Fox, director of the Heliophysics division, leads NASA’s efforts to explore the star that makes life possible on Earth: our Sun. Scientists who study heliophysics are looking at how the Sun impacts our planet and the rest of the solar system, as well as how we can protect astronauts, satellites and robotic missions from its harsh radiation. Scientists can also compare the Sun to other stars that host planets, leading to insights about which distant worlds might be able to host life.

“Ever since people first looked up, they’ve been looking at the bright light in the sky,” she said. “We are really the oldest science branch.”

A native of Hitchin, a small English market town, Fox also has a special connection to the Apollo 11 Moon landing. When she was just 8 months old, her father took her out of her crib, propped her up at the television and gave her a running commentary of the historic event.

“Dad takes credit (for my space science career),” Fox said. “To him, the best thing you could do in life was to work at NASA.” But since England didn’t have a space program, this seemed to Fox like a distant “pipe dream,” akin to winning a Grammy or an Oscar.

Fox attended an all-girls school where students were encouraged to follow their interests. Her mother also made sure she had opportunities try a wide variety of hobbies and pursuits. She never had the sense that particular subjects were “for boys” or “for girls.” In college, however, Fox was frequently one of the only women in her science classes. After earning a bachelor’s degree in physics, Fox entered a Master’s program in telematics (satellite and computer engineering), where she was in a cohort of four women out of 280 students. She then went on to complete a Ph.D. in space and atmospheric physics.

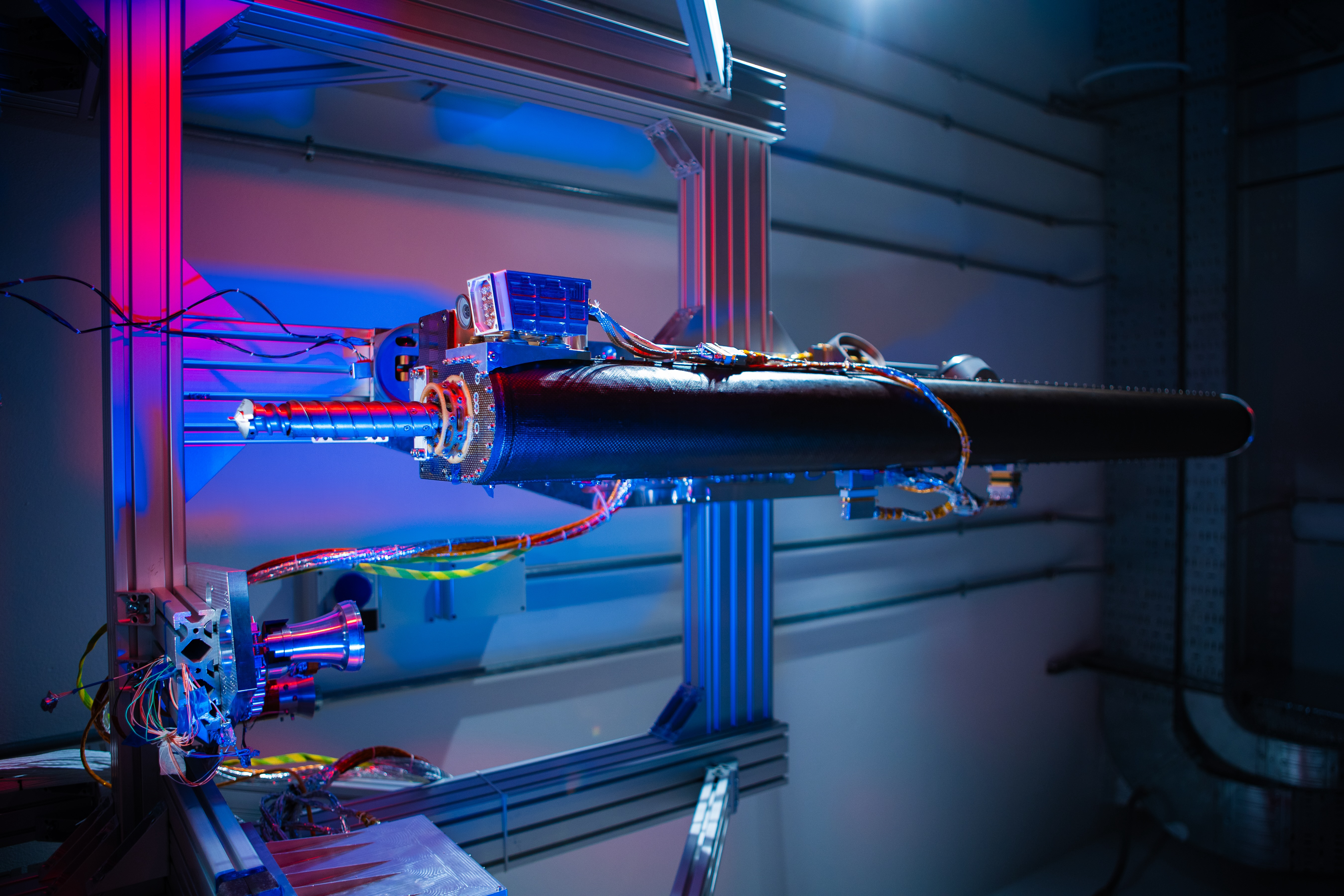

She moved to the United States for her postdoctoral fellowship at Goddard. The late Mario Acuña, a pioneer in the study of planetary magnetic fields, was a mentor there to Fox, and “really pushed me to do things that were outside my comfort zone,” she said. In 1998, she moved to the Johns Hopkins University/Applied Physics Laboratory. Recently, she served as the project scientist for NASA’s Parker Solar Probe, which launched in 2018 as the first mission to “touch” the Sun.

One of her more personal connections with the Sun was the 2017 solar eclipse, which she viewed from a field in Nebraska with her parents, who flew over from England, and her children. Her hopes of seeing the Sun blocked out by the Moon were nearly crushed by clouds and rain. But right at the big moment, the clouds parted and framed the Sun’s corona – it’s outer plasma layer – in all its splendor. “It was my first eclipse. It was doubly exciting,” she said.

She moved to NASA Headquarters to lead the Heliophysics division in September 2018. She has loved how everyone, from rocket engineers to custodians, are part of NASA exploration missions, and “Taking part in something so much greater than you.” Her message to the next generation of space fans is: There’s a career for everyone at NASA.

“If you think about the diversity of roles that take getting a mission into space, all different types of jobs come together,” she said. “If you want to work at NASA, there’s a job for you.”

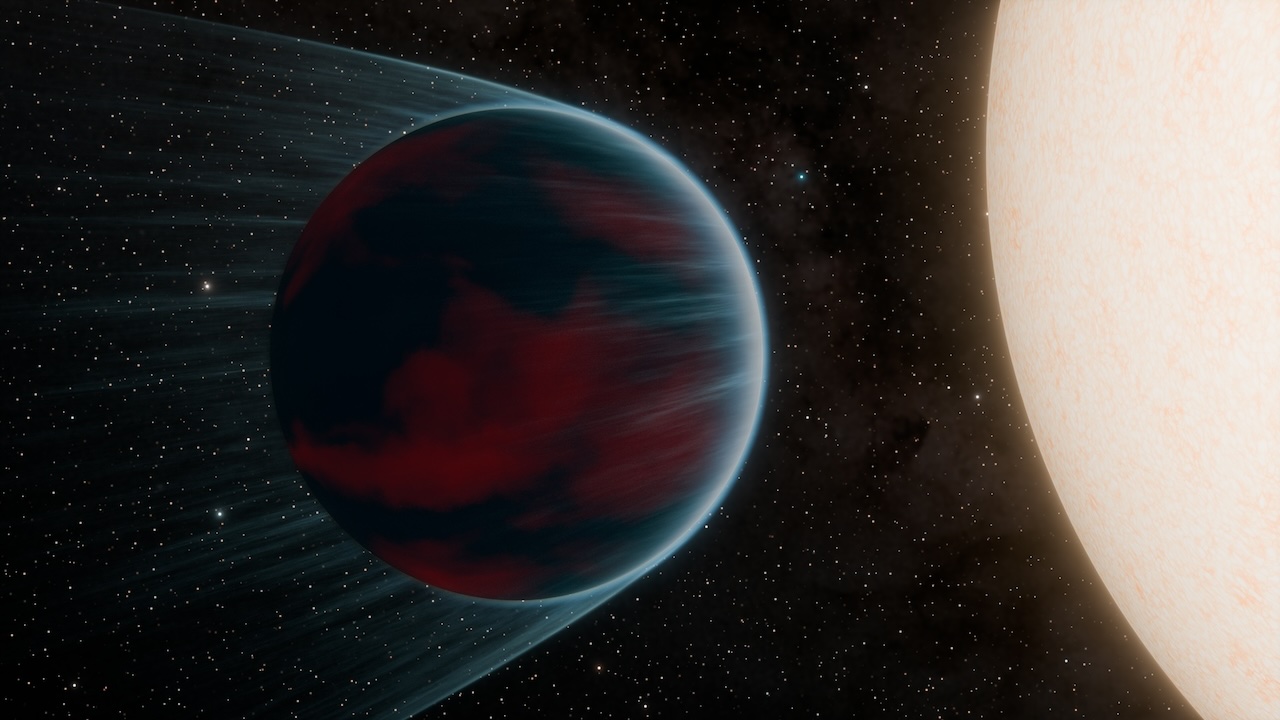

Lori Glaze leads the Planetary Science division, which focuses on space missions and research that seek to answer questions fundamental to how our solar system formed and evolved, and whether there are other worlds that could, or could have in the past, supported life.

When Glaze was growing up, her mother worked as an aeronautical engineer, and was very passionate about her work. From mechanical work on commercial airliners to the space shuttle program, Glaze’s mother persisted in what was a male-dominated field and didn’t think twice about it. She worked and grew in a field she loved, making a big impression on Glaze.

“That was a tremendous inspiration for me, as a young woman, seeing that a technical career, a career in leadership in a mathematical or scientific field, was possible,” Glaze said.

In 1980, when Glaze was a high school student in Seattle, she heard the blast of Mount St. Helens erupting. Silicate ash shards rained down on houses and cars, scratching windows like little pieces of glass. Between this experience and an exhibit about the eruption that blanketed Pompeii in 79 AD, Glaze became transfixed by volcanoes.

In college, she learned that volcanoes aren’t just on Earth. NASA’s Voyager mission had revealed the first proof of volcanic activity beyond our planet at Jupiter’s moon Io in 1979. Mars has the giant dormant volcano Olympus Mons, the tallest in the solar system. Venus holds our planetary neighborhood’s record for most volcanoes, although the jury is still out whether any are still active today. Glaze’s curiosity led her to wonder about the way lava flows, how eruptions happen and differences among volcanoes on different planets. She ended up getting bachelor’s and master’s degree in physics at the University of Texas, Arlington. While working at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), she earned a Ph.D. in Environmental Science from Lancaster University in the United Kingdom.

At JPL she worked on a concept for an orbiting volcano observatory and other Earth remote sensing research projects. After that, she spent over 10 years working for a private company, then moved to NASA Goddard. She continued pursuing her interest in how satellites can track volcanic eruptions on Earth and reveal the volcanic histories of worlds beyond our own.

Glaze has been involved with many NASA-sponsored Venus mission concept formulation studies, including as a member of the Venus Flagship Science and Technology Definition Team, as Science Champion for the Venus Mobile Explorer (2010), and Co-Science Champion for the Venus Intrepid Tessera Lander (2010). Before her move to NASA Headquarters in 2018, she also was the principal investigator of a Venus atmospheric entry probe concept called Deep Atmosphere Investigation of Noble gases, Chemistry, and Imaging (DAVINCI).

Over the last 10 to 15 years, Glaze has witnessed a huge growth in opportunities for women like herself to work in leadership positions. As recently as two years ago, Glaze realized she was the only woman at a particular study meeting, but said she still felt her contributions were respected and valued. She has found NASA’s Science Mission Directorate especially welcoming.

“It’s the most diverse group of people I’ve ever worked with and it’s the kind of place where you feel like everyone’s ideas are being heard; and really moving along and advancing our understanding in how we want to go about doing science at NASA,” Glaze said. “I think it’s a great place to be today.”

Astrophysics, the other science division at NASA, is led by Paul Hertz.