Bert Pasquale, Optical Designer of the Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope, Takes on the Complex Problems

Name: Bert A. Pasquale

Title: Roman Space Telescope Optical Systems Design Lead, Optics Branch Optical Design Group Leader

Formal Job Classification: Optical Physicist, Optical Design and Analysis

Organization: Code 551, Optics Branch, Instrument Systems & Technology Directorate

What has been your role been at Goddard and how does that support NASA’s mission?

First beginning as a contractor in 1992, then joining NASA as a civil servant in 2005, I have worked on well over a hundred aerospace optical designs. As an optical designer, I usually work directly with science teams on a lot of proposal and pre-Phase-A concepts, where the design is quickly evolving with many trade studies.

My first flight project was Cassini’s Composite InfraRed Spectrometer (CIRS), which launched to Saturn in 1997. I remember a meeting my first week of work where I hand-sketched a complex 3D opto-mechanical component for the internal reference interferometer, which was implemented in the flight design. The CIRS Engineering Unit is now on display in the Building 36 lobby at Goddard.

I worked on several space observatory concepts in the 2000s, including the Dark Energy Space Telescope (DESTINY) — a precursor to the Roman Space Telescope — and the Advanced Technology Large Aperture Space Telescope (ATLAST) concepts. The ATLAST optical models became seeds for the Large UltraViolet Optical InfraRed (LUVOIR) and Origins Space Telescope (OST) proposal designs. I’ve always loved optics and science so getting to work on cutting-edge instruments is a blast.

In 2012, NASA inherited the 2.4-meter space telescope optical chassis that is now the basis for the Roman Space Telescope design. I served as the optical system design and analysis lead for the payload including the telescope, Wide Field Instrument, and the descoped Integral Field Channel.

How did you fall in love with optics?

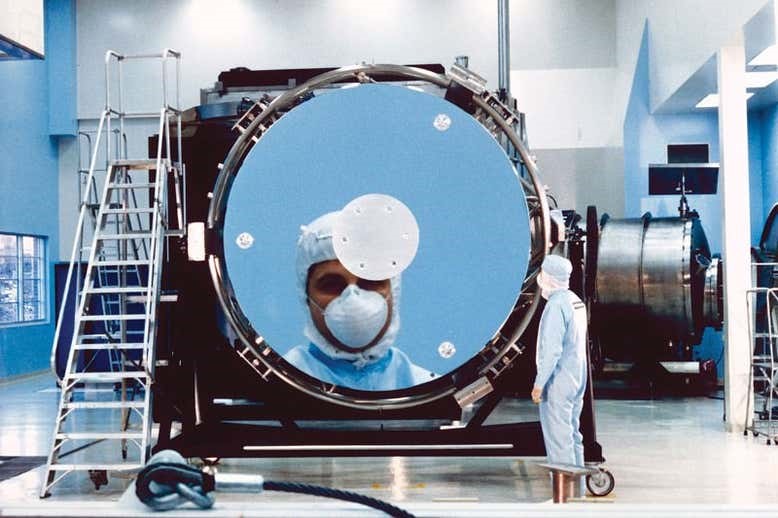

As a high school student in the ’80s, I was fascinated by astronomy and the instrumentation used, but was particularly enamored by the then-upcoming Hubble Space Telescope. The Sunday newspaper’s magazine published a picture of a technician standing in front of Hubble’s primary mirror with the story of its development. The power of that single image further inspired my love for optical systems. I asked for a telescope for my high school graduation. I still use it today.

I gravitated to both engineering and photography and enrolled in the optics program at the University of Rochester. Our professor for the graduate lens design course was on the Hubble failure review team and would give us monthly updates as they figured out what the error was and how it was caused. Even though I did not specifically plan to become a space telescope designer, one of my first tasks in the workforce was supporting analysis for the first Hubble servicing mission Independent Verification Team.

I also have an optics-related artistic outlet in my photography. About 15 years ago, I began creating professional-level photographic imagery in my own artistic style, leading to my master photographer accreditation and an international award-winning capture of the final space shuttle launch. In 2017, I traveled to Nashville to capture the solar eclipse. My favorite composition combined the total corona with “diamond ring” images.

How do your art and engineering passions enhance each other?

These pursuits are not unrelated. My art informs my engineering, my engineering informs my art. The beauty of technical design and the technicality of my photographic style go hand-in-hand. Who I am is both encompassed by, and also reflected in, both. I embraced digital imaging as early as 1998, and I recently designed an illumination system drawing on my familiarity with photo studio lighting design.

From a photographer’s perspective, Roman’s Wide Field Instrument (WFI) is an 8-inch-by-10-inch, 300-megapixel digital back camera with an 18,500mm f/8 lens. The WFI can capture an area of sky the size of the Moon in a single observation – 90 times more sky than Hubble’s Advanced Camera for Surveys, and 220 times more sky than Hubble’s infrared mode. Because Roman’s L2 orbit does not carry Hubble’s low-Earth-orbit observing limitations, it can potentially outpace Hubble’s infrared survey capabilities by a factor of 360. When I realized this, we coined the phrase “A Year is But a Day!” in comparison.

How did teamwork move Roman forwards?

Working as a team was essential, of course. The 1958 essay “I, Pencil” by Leonard E. Read bestowed a deep understanding of the breadth of skills necessary for creating even a common object. No one person could design this observatory; it involved every engineering and support discipline at Goddard.

Our optical team also has a diverse skill set, and we regularly coordinated between design, integration and testing (I&T), wavefront sensing and systems. Having an understanding of the I&T procedures plus my previous hands-on experience in characterizing as-built optical systems allowed us to design the payload and WFI optical components with verifiable tolerances. The Phase-A error budget spreadsheet for predicting on-orbit performance via adjustable parameters grew to 100 MB in size. Monte-Carlo optical models then simulated all steps from fabrication to on-orbit for verification. This allowed the project to adjust costs and schedules to meet realistic fabrication and alignment allocations with the assurance that all science goals can be met.

The team extended beyond the Goddard campus. For several years, other designers and I were able to fully participate in science team meetings. The instrument-then-payload manager Dave Content was very supportive of this, and it made a big difference. These direct science/design interactions often moved the project forward and prevented confusion and swirl.

Industry partners are also part of our team. We made a radical architectural change in mid-Phase-A, with the challenge to simplify the telescope-to-instrument interfaces. This required tight coordination with both the telescope vendor (Harris Corporation) and NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Southern California, which is building the Coronagraph Instrument. When Tom Casey, the payload systems engineer, asked what was needed to complete this quickly, he empowered us to work directly as a badge-less team, on-site with the telescope vendor. We pulled it off, ahead of schedule!

How were you involved with the redesign?

Nerses Armani, our lead mechanical designer, and I led the engineering side of the effort in 2016. The role we played was to coalesce all the requirements into a working optical and opto-mechanical design. It required intimate understanding of the system drivers; We had to understand the physical, thermal, structural and science constraints… all while including heritage hardware. We had considered the option years before, but by now the team and I had the full systems understanding to pull it together. I tell the story of after evaluating the strengths and weaknesses of 20 architecture options during one of the off-site meetings, the next morning we presented a 21st design, which is the one we went with. We are very proud of the first NASA Great Observatory with an in-house optical and observatory design!

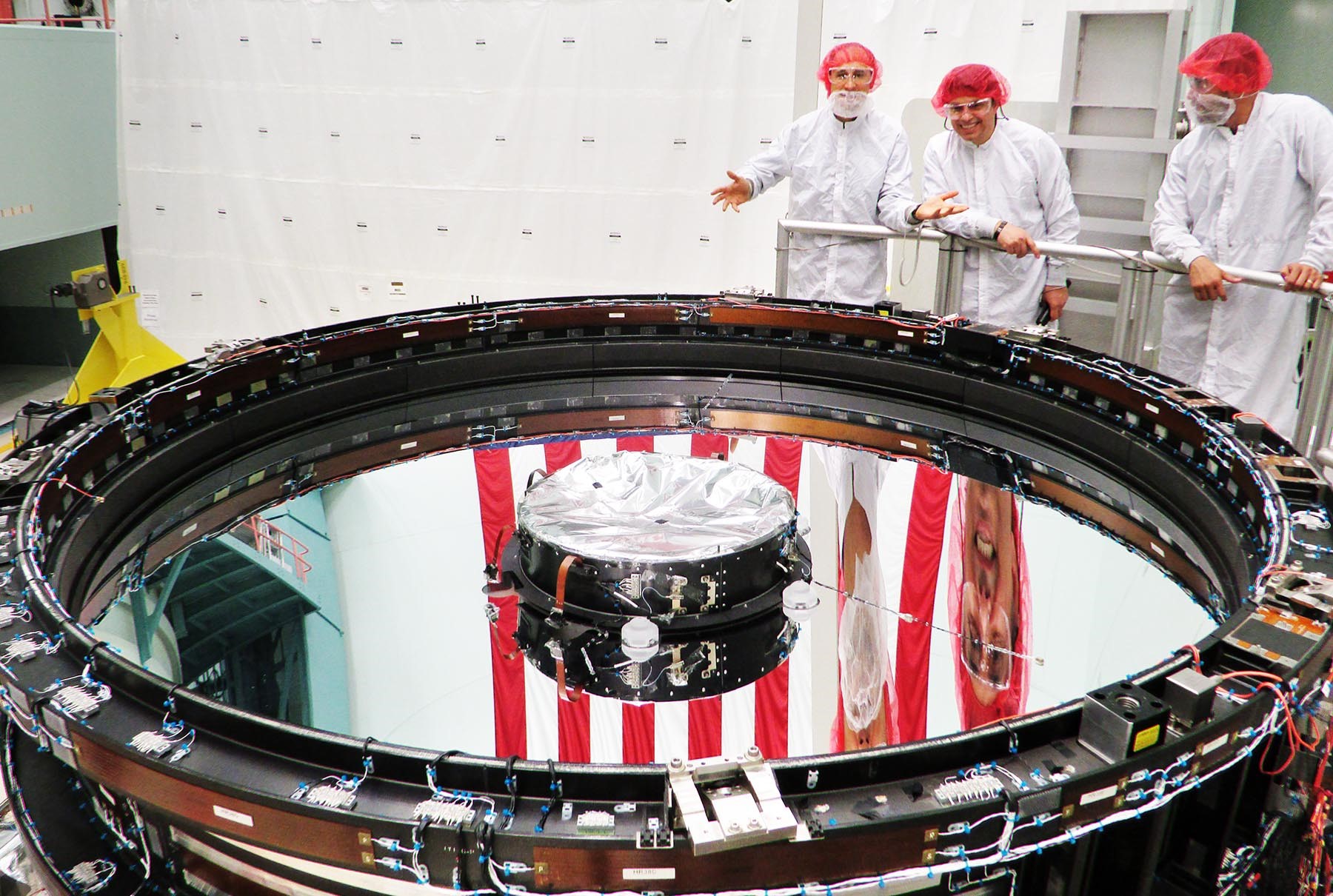

Understanding the existing hardware was essential, as the modifications that were made needed to have minimum impact. During a site hardware inspection, I was photographed reflecting off the Roman primary mirror, taking me back to the image that inspired me when a teenager.

Teamwork also mattered in the small things. For example, even a simple task such as sizing the mirror apertures required an understanding of the mechanical dynamics, physical constraints and how the science teams would process the data. I sought to communicate this as much as possible via tables and detailed drawings. In the end, providing a forum for full communication with the vendor allowed this to close perfectly.

How did you change while working on Roman?

Roman was a game-changing experience for my understanding of system-oriented design. In the movie “The Matrix,” when a fighting program is uploaded to Neo, he suddenly gasps, “I know Kung-Fu!” Well, there was a point when I realized, “I know what it takes to design a space telescope!” Admittedly, that was a multi-year upload, but a bit of a rush, just the same. (However, now I’m even more aware of what I don’t know.)

Working with the Roman science team while also watching the James Webb Space Telescope being built, I fell in love with astrophysics. I have ravenously taken in hundreds of YouTube videos on the universe and science. I’ve written five papers connecting the design and science of Roman (before its name was changed from WFIRST), including an article in Physics World magazine. I love how scientific goals and instruments’ functions can be communicated through media and envision how it could be taken even further. But the most significant change comes from the lessons learned.

What has working on Roman taught you?

Communication is king. Our telescope systems engineer had the motto, “No bad news late.” Delays in design progress are usually acceptable when you’re in tight communication with the team. But if you’re distant, you can be performing vital work that is overlooked or regarded as insignificant. That hurts everyone and I’ve got these as lessons learned.

Communication is also the foundation of building concurrent engineering teams with a systems mindset. When caring about your carbon-based resources is your priority, the design problems will be resolved. While there is so much you can’t control, an optimized working environment will optimize the technical progress, which is the key to project efficiency. This means not only delivering an optimal product on schedule, but doing so with minimum errors, go-backs and preventing dysfunctional situations. Without fostering continuity in the concurrent engineering team, mistakes could be made such as incorrect interfaces resulting in months of delays. I’ve turned my full lessons learned list into a concept for “Integrated Concurrent Engineering Teams for Increased Efficiency in Flight Projects.”

Finally, all team members must be empowered to take initiative. In 2018, my initiatives focused on making sure design interfaces between various subsections were closed out for Phase-B. The fall months were spent on reconciling the telescope-to-Instrument interface with our vendors and updating critical analysis of optical performance. I was then able to turn my attention to ramping up the design trades of the Low Dispersion Prism, a late addition, which needed to simultaneously be brought up to Phase-B level analysis. Even though this was interrupted by the 2018-2019 furlough, we were able to synthesize the results the third week after returning.

What did you learn about yourself?

Being curious comes naturally to me, and asking questions is an essential part of any design team, including about yourself. I find assessment tools such as DISC, StrengthsFinder and Enneagram useful in this regard. For example, my StrengthsFinder results indicate I’m in my sweet spot working in a tight team to envision solutions to complex systems involving many moving parts and using relationships to find a workable solution that maximizes impact. My Enneagram (Type 1) also points to being a creative reformer and perfectionist.

While these assessments speak to my ability to simultaneously envision all the details and how they work together, that doesn’t automatically make life easy. These both carry a cautionary advisory to maintain communication outside of my internal thoughts as I consider options. Having ADD/OCD tendencies, I have to perform exercises to recognize or even re-train my responses to situations. It’s also very important for me to have close physical proximity to my managers and collaborators.

You also have to understand how you function within the team. Brené Brown’s address to NASA on March 5, 2020, from Johnson Space Center in Houston pointed out how the fear of being irrelevant triggers the shame response of self-protection, versus having the vulnerability essential to courageous leadership. That hit home for me. It takes a manager truly skilled in human dynamics to effectively utilize the unique strengths of all their carbon-based resources: people. I’d encourage teams to do a coach-led assessment of some sort when forming and maintaining their culture. Each person has to understand how their colleagues work, function, communicate, think and respond differently than they do. I’ve made that mistake, too.

How have you transferred what you have learned through mentoring?

My time on Roman gave me a much broader picture of what to expect going into a flight project. When mentoring the younger designers in my branch, we often have conversations on the importance of not only the technical but also the leadership and growth areas involved.

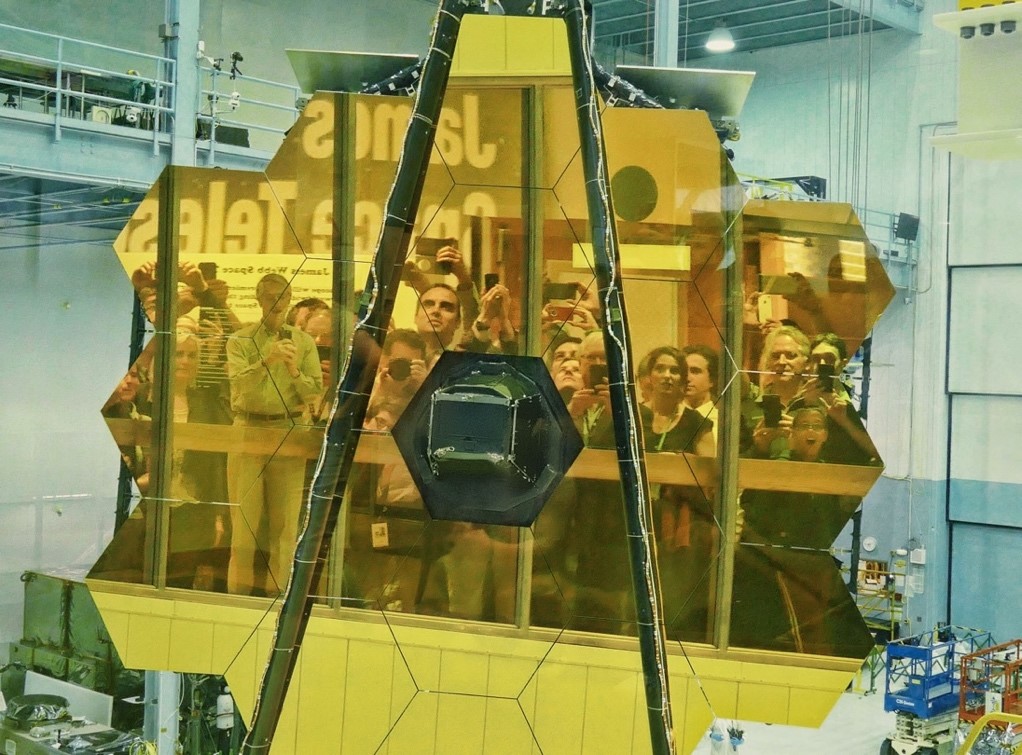

On Star Wars Day (“May the Fourth”), 2016, I brought my 10-year-old son to the first turning around of the completed Webb telescope primary mirror at the Building 29 observation deck. I captured his amazement as he saw his own reflection in the gold mirror segments. At the same moment, across the mirror is seen Dr. John C. Mather, Nobel laureate and Webb’s principal investigator. That image tied the past, present and future together for me.

After seeing his reflection in the Webb mirrors, I told my son that he was the youngest person in the world to have done so. He thought for a moment and asked, “Can we call the record book people?” This unofficial record held for over a year.

What have you been doing recently?

The past year I have still been involved with the only remaining in-house Roman optical design work: the Wide Field Instrument’s Grism and Low-Dispersion Prism elements and the Coronagraph Instrument’s Zero Optical Deviation Prism. These elements will be used to analyze the spectrums of galaxies, supernovae and exoplanets. I also worked on the design team for ground support equipment to test and pre-calibrate the Wide Field Instrument being built by our other prime industry partner, Ball Aerospace. Our simplified design allowed the WFI to stay on schedule.

This is now a period of cross-training for me. I’m developing a new mission proposal collaboration with UC-Berkeley and Nobel laureate Saul Perlmutter to leverage the work and science of the descoped Integral Field Channel. This has involved establishing a team of astrophysicist collaborators in Goddard’s Exoplanets and Stellar Astrophysics Laboratory while engaging astrophysics stakeholders and new business leads across Goddard’s Engineering and Technology Directorate. This year I am also working on a major contracts evaluation for the directorate and participating in systems engineering and project management trainings.

My priority is preparing for the next mission that comes out of the 2020 Astrophysics Decadal Report, should it result in Goddard leading another large space telescope project. I have been coordinating with several of the proposal developers, and we are ready to meet that challenge. I look forward to the new and complex problems for our teams to solve.

How are you involved in Goddard’s diversity and inclusion (D&I)?

I participated in a nine-session Diversity Dialogue Project group. In each two-hour session, we discussed a different topic. It was nice to have a safe space to explore difficult issues, as it emphasized allowing others and yourself to respectfully express who you are without fear. It was a positive experience that furthered my awareness about various topics affecting the culture around me. I see art, work, love, worship, in fact all of life, as a continuum. I very much enjoy having conversations with people from different viewpoints; my “complex problem solving” brain enjoys making new connections between system-level issues, from cultural topics to the co-benefits of scientific pursuit and faith. I believe this bent has helped me bring resolution in what is often an unnecessary conflict of worldviews. I have been able to initiate D&I conversations in my branch and work groups.

What surprising things may people not know about you?

I have been married to my college sweetheart, Holly, for 27 years and have been a father for exactly half that time. I have rock-climbed in 11 states and done photoshoots in 32, plus two other countries. My fine art photography has been exhibited at various galleries including most recently the Dupont Underground in Washington, D.C. I have not only photographed, but officiated weddings (although not at the same time!). I have been a lay counselor for 12 years under teachings of Dr. Dan Allender and his local progeny Dr. Bill Clark. I play drum set and marimba with my church’s worship team. During the COVID-19 quarantine I learned to bake artisan sourdough breads, and I grow a variety of superhot peppers to make hot sauces, both of which I enjoy sharing with friends. I moderate an online discussion group of the writings of Thomas Sowell and related socio-economic intellectuals and am a diehard fan of the rapper NF, a genius yet relatable expositor of the struggles of life.

What is your “six-word memoir”?

Love God, serve people, be present.

By Elizabeth M. Jarrell

NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center