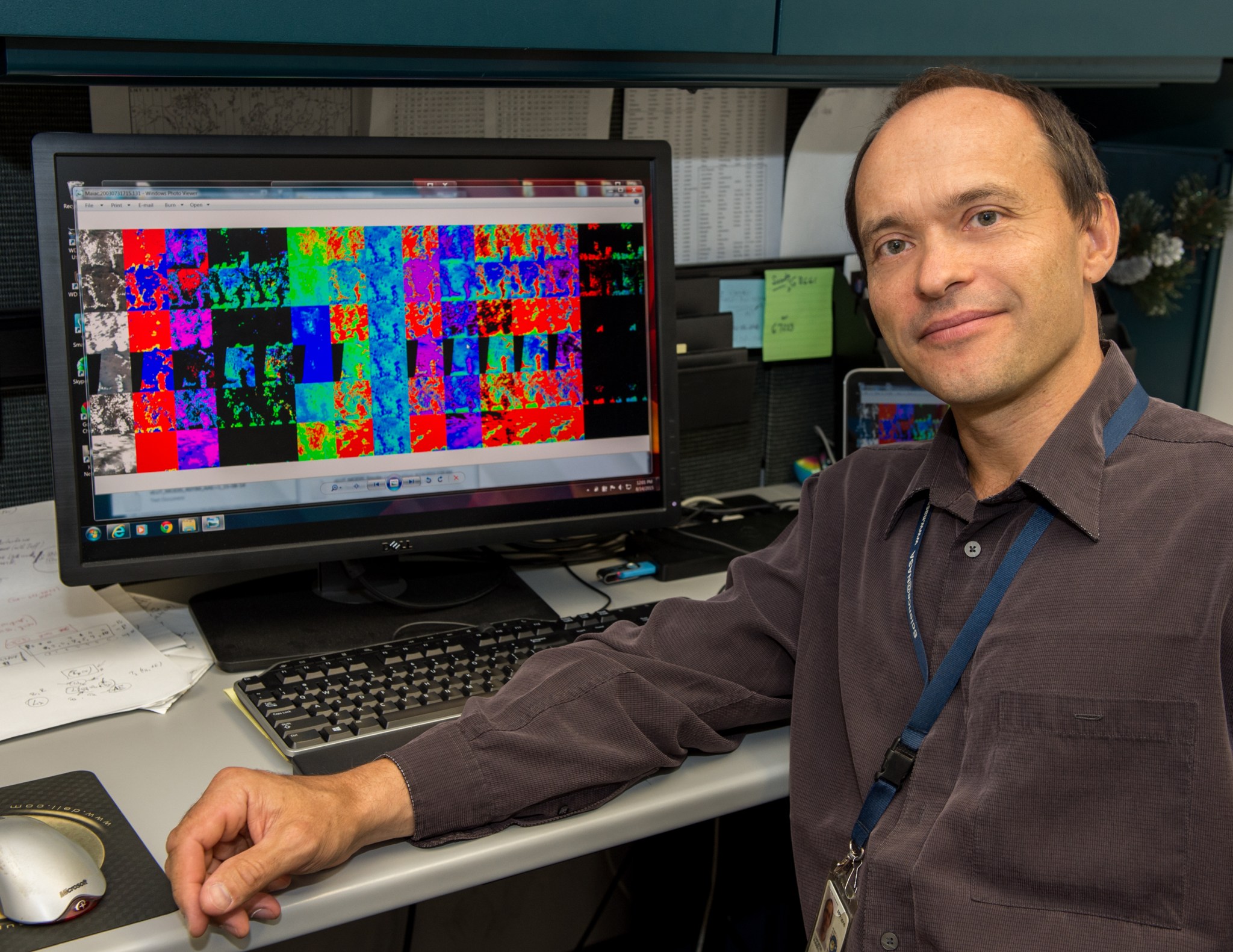

Name: Alexei I. Lyapustin

Formal Job Classification: Physical research scientist

Organization: Code 613, Climate and Radiation Laboratory, Sciences Directorate

Alexei Lyapustin takes the air out of things, for science!

What do you do and what is most interesting about your role here at Goddard? How do you help support Goddard’s mission?

I am a principal investigator for the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS), Visible Infrared Imaging Radiometer Suite (VIIRS) and the Earth Polychromatic Imaging Camera (EPIC) of the Deep Space Climate Observatory (DSCOVR). My goal is to determine reflectance of the Earth’s surface by making atmospheric correction of satellite data. The atmosphere absorbs and scatters the sunlight. I need to remove these effects, as if we were observing the Earth from space without any atmosphere.

How do you make atmospheric correction?

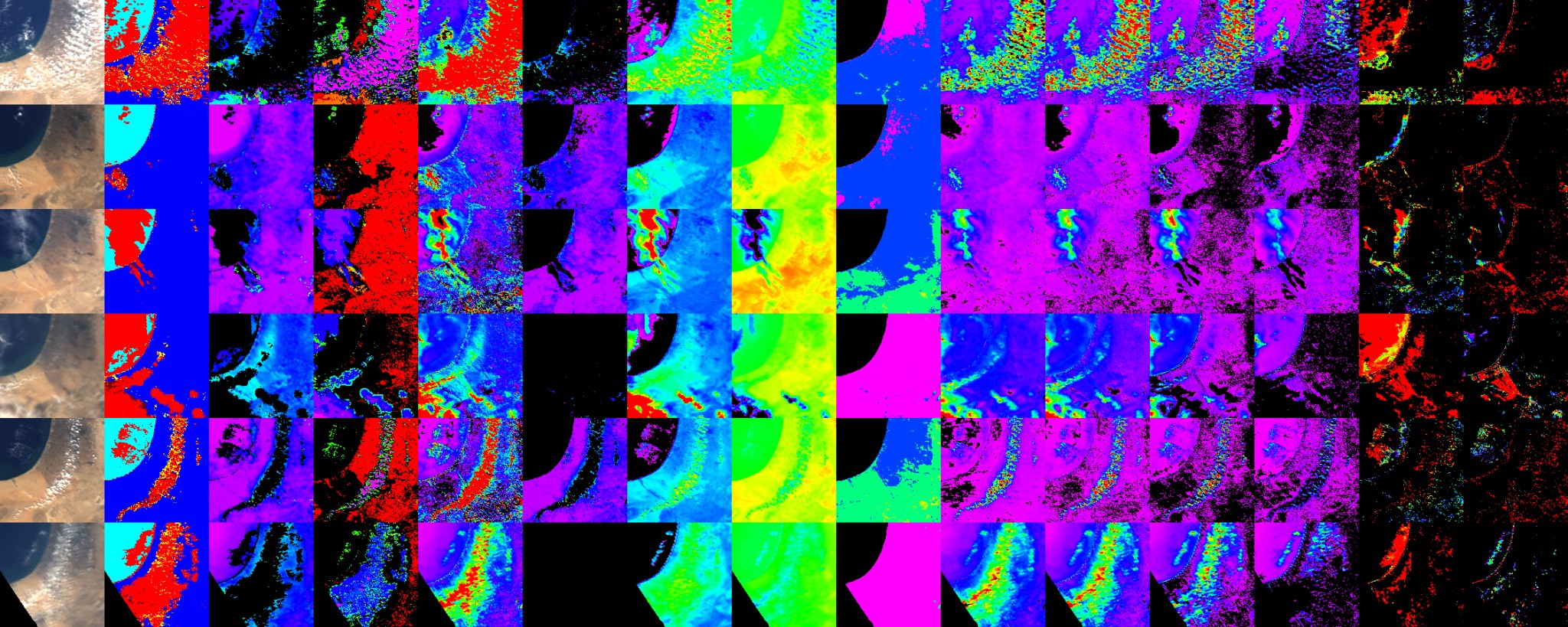

Atmospheric correction requires you to become an interdisciplinary scientist. First, we need to detect clouds, then determine the amount and properties of aerosols in cloud-free areas, and finally determine surface reflectance. When we detect snow on the ground, we also provide snow grain size and snow fraction, which is the part of the surface actually covered by snow. I develop algorithms to isolate each of these factors.

To describe how the surface reflects light from different angles over the same locations, we collect data from different satellite overpasses. Each looks at the surface at a different angle. These data are processed together to provide a bidirectional reflectance distribution function model describing the full pattern of angular reflection. This model helps predict surface reflectance for the next satellite view, which we need in remote sensing, as well as the total reflection at all angles, which is needed in Earth radiation models. The angular pattern also carries information about the 3-D structure of the surface such as the height and distance between trees. We cover the entire Earth every day and provide such data for each 1-km pixel.

Where were you born and raised?

I was born on the eastern slopes of the Ural Mountains in Russia, which was then the Soviet Union. I grew up in Oktyabrskii, a city of about 100,000 people, also near the Urals. Oktyabrskii is named after the October 1917 Red Revolution, which is November in the Gregorian calendar followed in the U.S.

What attracted you to science?

I was always interested in exact sciences. I guess I liked mathematical logic. As a child, I used to go to the local public library. Among other books, they had a handful of highly technical scientific books which I tried to read without much success. They also had a more popular book on cosmology by Viktor Shklovsky, which made a great impression on me and nurtured my desire to become a scientist.

Why were your university years such an interesting scientific time?

I earned my master’s degree in physics from the Moscow State University in 1987 and my Ph.D. from the Space Research Institute in Moscow in 1991.

I attended graduate school during a very interesting time. Scientists realized that we needed to measure satellite signals from different angles to get both aerosols and surface reflectance. I worked on the Soviet Union’s first multi-angle experiment from the Russian space station “Salut-7.” It was an unbelievable experiment: during the overpass over an area with high air pollution, they rotated the entire station such that the spectrometer could see the same spot from a wide range of angles. It must have been very expensive, but also so exciting! I developed the first method to process this information.

Later, I participated in the planning and processing of similar experiments from the Russian space station “Mir.” Interestingly, the word “mir” means both “world” and “peace” in Russian.

What was your life like in the Soviet Union during perestroika?

I received my Ph.D. during the time of perestroika in Russia. The Soviet system was falling apart. Funding for science was at an extremely low level. I had a couple of very difficult years. Inflation was unbelievable. One of my grants was delayed for six months. By the time I got the funds, they were worth less than one-fifth of their original value.

For a couple of months each year, I had barely enough money to buy just one loaf of bread every other day, and my colleague who was in a similar situation would do the same the alternate day. It would be our shared lunch. I could afford to pay for the bus only one way to work, so I jogged back home in the evenings, eight kilometers, or about five miles. But I was young.

Also, my wife left in 1993 to attend graduate school at Johns Hopkins University on a student visa and had our three kids. So, in a way, I felt lucky, because some of my colleagues were in the same dire situation and yet had to somehow also provide for their families.

In retrospect, it turned out to be a useful period of my life – it matured me: you have to do what you have to do, whatever the circumstances.

How did you come to the U.S. and Goddard?

Around 1988, while I was doing my Ph.D., I met Bob Murphy who worked at NASA Headquarters at the time. Bob was one of the first high-ranking U.S. individuals to come to the Soviet Union to visit academic institutions after the fall of the iron curtain. We talked extensively about science.

In late 1996, he contacted me again and offered me a job supporting MODIS. I accepted immediately and came to Goddard in 1997, finally rejoining my family four years after they had left.

How did Bob Murphy influence you?

I think that our assessment of scientific research was somewhat similar. During Bob’s visit to the Space Research Institute, I gave a very straightforward and detailed critique of the latest research at NASA. Later, it turned out that I was talking about prior works. Even in the best library in Moscow, the Leninsky Library, the western journals were often delayed by at least one year, so I was not aware of the latest works, which were excellent. Bob liked my earnest, non-political assessments, attitude and drive.

Bob is a wonderful person who greatly helped me and my family. He also helped me to adjust to life here. Among other things, after so many years, we are still using some of the furniture and kitchenware he had given us in that first year. We remain good friends.

What was your biggest cultural challenge?

For years I could not admit that I didn’t know something. I was stunned at how the top-level scientists here could admit that they didn’t know something. I also couldn’t say that I was wrong or that I had made a mistake. It took me years to overcome this.

In the old Soviet system, if you admitted that you didn’t know something, it would make you look weak in front of other scientists. They would often put you down with more questions. So you had to act very confident all the time.

I also learned early on to continue working hard until I had solved a given problem. I’m not afraid to take on big problems in aerosol science and remote sensing. I never give up on a problem, however difficult. I won’t stop until I solve it. They will crack in the end.

I remember that it took me six months working weekends and holidays to solve one particular problem. I still work almost every day, including most weekends.

Goddard is the best place in the world to be. It is a unique melting pot of engineers making instruments and scientists processing the measurements and using the data, as, for example in climate models.

Are you close to other scientists from the former Soviet Union at Goddard?

There are quite a few of us here – a group of about my age and another group about six to eight years older than us. We often get together and discuss just about everything. It is always relaxing to speak in your mother tongue.

This group was very important to me when I first came here so I didn’t get nostalgic or homesick. It is good to be able to joke and good-naturedly laugh at each other the way we used to in the Russian culture.

Tell us about your current work group.

I currently have two scientists in my group and am hiring one more. I have very high standards and requirements. Both of my scientists are truly outstanding specialists in their area. I just tell them the problem and they bring me the solution. I completely trust that they will solve a problem in the most efficient way possible, and they always do.

What advice would you give to young scientists?

Don’t be afraid. Take on the most challenging problems. If you cannot solve them, it only means that you are missing something, some consideration or perspective. Be persistent. In the end, you will find a solution. When you get to solve some of the most challenging problems, you get an unbelievable feeling. Your confidence increases tremendously.

What do you do to relax?

I play sports, especially tennis. I also garden.

Describe yourself in six words.

Interdisciplinary, determined, disciplined, reliable, optimistic, confident.

By Elizabeth M. Jarrell

NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, Md.

Conversations With Goddard is a collection of Q&A profiles highlighting the breadth and depth of NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center’s talented and diverse workforce. The Conversations have been published twice a month on average since May 2011. Read past editions on Goddard’s “Our People” webpage.