Radiation

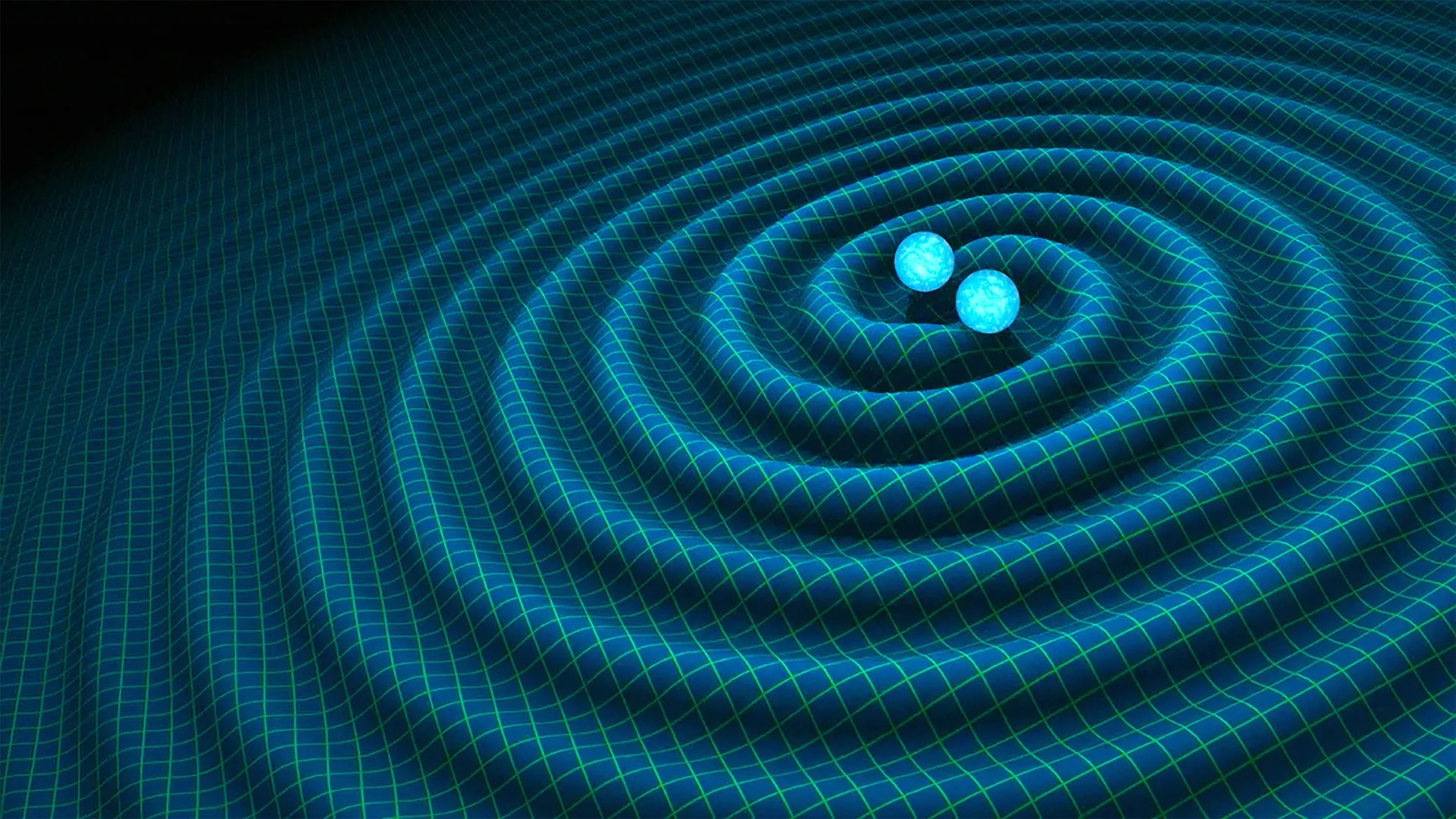

The first hazard of a human mission to Mars is also the most difficult to visualize because, well, space radiation is invisible to the human eye. Radiation is not only stealthy, but considered one of the most menacing of the five hazards.

Above Earth’s natural protection, radiation exposure increases cancer risk, damages the central nervous system, can alter cognitive function, reduce motor function and prompt behavioral changes. To learn what can happen above low-Earth orbit, NASA studies how radiation affects biological samples using a ground-based research laboratory.

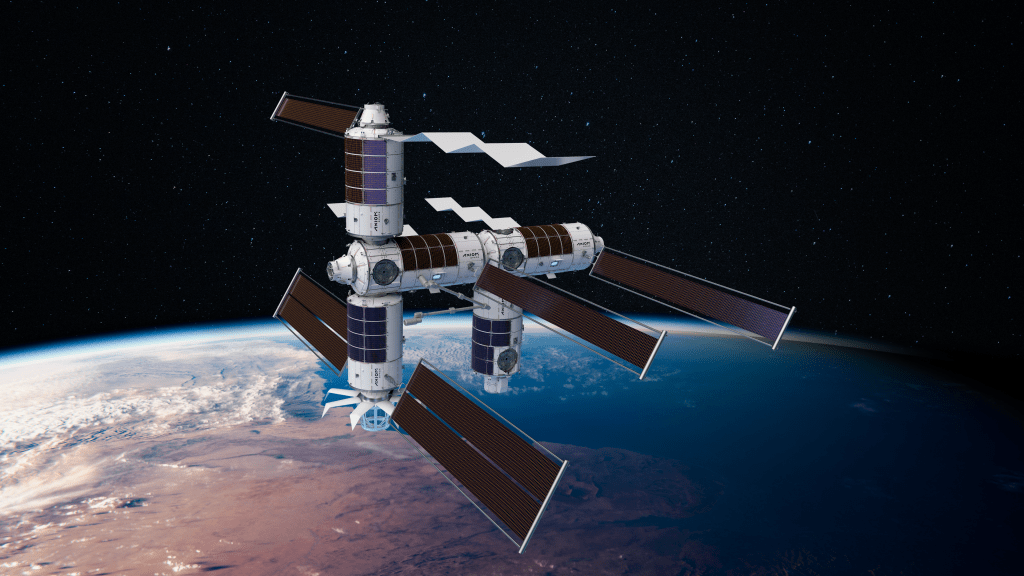

The space station sits just within Earth’s protective magnetic field, so while our astronauts are exposed to ten-times higher radiation than on Earth, it’s still a smaller dose than what deep space has in store.

To mitigate this hazard, deep space vehicles will have significant protective shielding, dosimetry, and alerts. Research is also being conducted in the field of medical countermeasures such as pharmaceuticals to help defend against radiation.

Isolation and Confinement

Behavioral issues among groups of people crammed in a small space over a long period of time, no matter how well trained they are, are inevitable. Crews will be carefully chosen, trained and supported to ensure they can work effectively as a team for months or years in space.

On Earth we have the luxury of picking up our cell phones and instantly being connected with nearly everything and everyone around us. On a trip to Mars, astronauts will be more isolated and confined than we can imagine. Sleep loss, circadian desynchronization, and work overload compound this issue and may lead to performance decrements, adverse health outcomes, and compromised mission objectives.

To address this hazard, methods for monitoring behavioral health and adapting/refining various tools and technologies for use in the spaceflight environment are being developed to detect and treat early risk factors. Research is also being conducted in workload and performance, light therapy for circadian alignment, phase shifting and alertness.

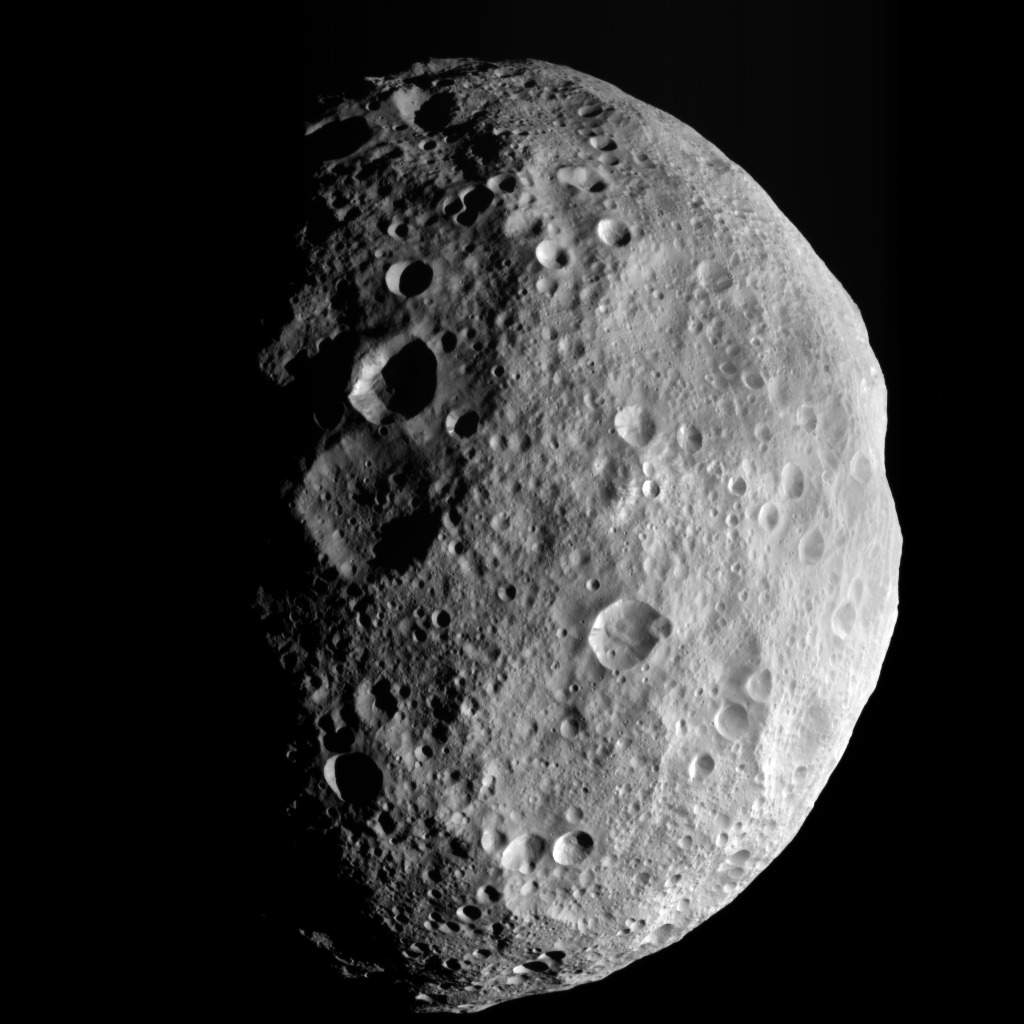

Distance from Earth

The third and perhaps most apparent hazard is, quite simply, the distance. Mars is, on average, 140 million miles from Earth. Rather than a three-day lunar trip, astronauts would be leaving our planet for roughly three years. While International Space Station expeditions serve as a rough foundation for the expected impact on planning logistics for such a trip, the data isn’t always comparable. If a medical event or emergency happens on the station, the crew can return home within hours. Additionally, cargo vehicles continual resupply the crews with fresh food, medical equipment, and other resources. Once you burn your engines for Mars, there is no turning back and no resupply.

Planning and self-sufficiency are essential keys to a successful Martian mission. Facing a communication delay of up to 20 minutes one way and the possibility of equipment failures or a medical emergency, astronauts must be capable of confronting an array of situations without support from their fellow team on Earth.

Gravity (or lack thereof)

The variance of gravity that astronauts will encounter is the fourth hazard of a human mission. On Mars, astronauts would need to live and work in three-eighths of Earth’s gravitational pull for up to two years. Additionally, on the six-month trek between the planets, explorers will experience total weightlessness.

Besides Mars and deep space there is a third gravity field that must be considered. When astronauts finally return home they will need to readapt many of the systems in their bodies to Earth’s gravity. Bones, muscles, cardiovascular system have all been impacted by years without standard gravity. To further complicate the problem, when astronauts transition from one gravity field to another, it’s usually quite an intense experience. Blasting off from the surface of a planet or a hurdling descent through an atmosphere is many times the force of gravity.

Research is being conducted to ensure that astronauts stay healthy before, during and after their mission. NASA is identifying how current and future, FDA-approved osteoporosis treatments, and the optimal timing for such therapies could be employed to mitigate the risk for astronauts developing premature osteoporosis. Adaptability training programs and improving the ability to detect relevant sensory input are being investigated to mitigate balance control issues. Research is ongoing to characterize optimal exercise prescriptions for individual astronauts, as well as defining metabolic costs of critical mission tasks they would expect to encounter on a Mars mission.

Hostile/Closed Environments

A spacecraft is not only a home, it’s also a machine. NASA understands that the ecosystem inside a vehicle plays a big role in everyday astronaut life. Important habitability factors include temperature, pressure, lighting, noise, and quantity of space. It’s essential that astronauts are getting the requisite food, sleep and exercise needed to stay healthy and happy.

Technology, as often is the case with out-of-this-world exploration, comes to the rescue in creating a habitable home in a harsh environment. Everything is monitored, from air quality to possible microbial inhabitants. Microorganisms that naturally live on your body are transferred more easily from one person to another in a closed environment. Astronauts, too, contribute data points via urine and blood samples, and can reveal valuable information about possible stressors. The occupants are also asked to provide feedback about their living environment, including physical impressions and sensations so that the evolution of spacecraft can continue addressing the needs of humans in space. Extensive recycling of resources we take for granted is also imperative: oxygen, water, carbon dioxide, even our waste.