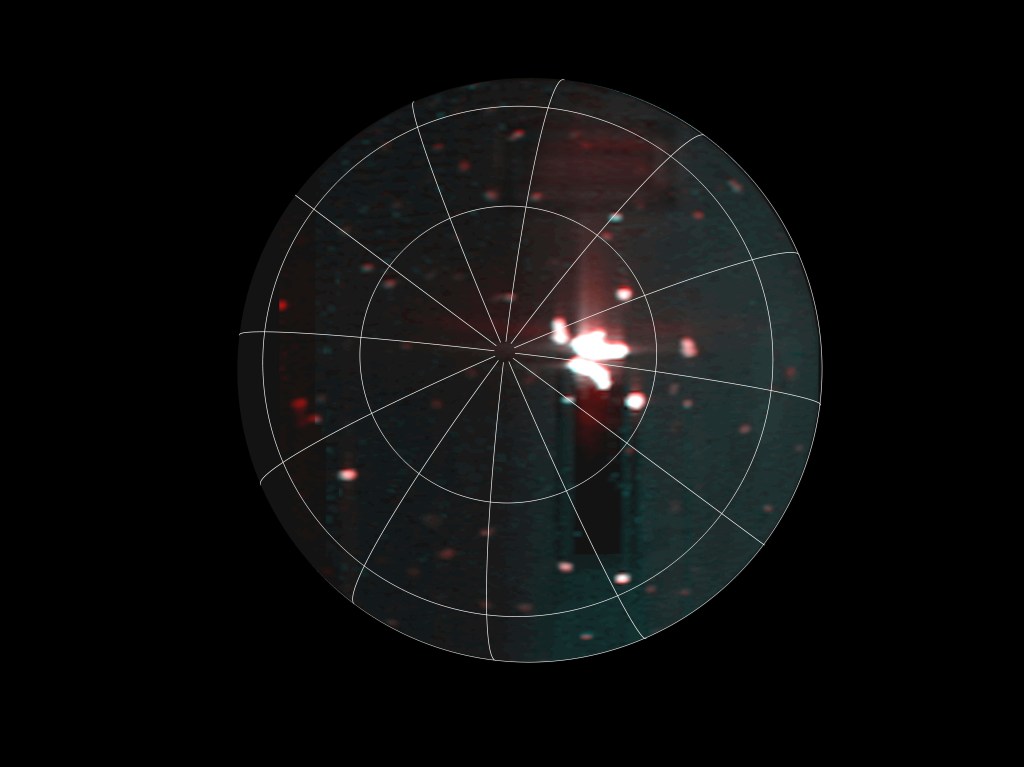

NASA’s Interface Region Imaging Spectrograph (IRIS) has provided scientists with five new findings into how the sun’s atmosphere, or corona, is heated far hotter than its surface, what causes the sun’s constant outflow of particles called the solar wind, and what mechanisms accelerate particles that power solar flares.

The new information will help researchers better understand how our nearest star transfers energy through its atmosphere and track the dynamic solar activity that can impact technological infrastructure in space and on Earth. Details of the findings appear in the current edition of Science.

“These findings reveal a region of the sun more complicated than previously thought,” said Jeff Newmark, interim director for the Heliophysics Division at NASA Headquarters in Washington. “Combining IRIS data with observations from other Heliophysics missions is enabling breakthroughs in our understanding of the sun and its interactions with the solar system.”

The first result identified heat pockets of 200,000 degrees Fahrenheit, lower in the solar atmosphere than ever observed by previous spacecraft. Scientists refer to the pockets as solar heat bombs because of the amount of energy they release in such a short time. Identifying such sources of unexpected heat can offer deeper understanding of the heating mechanisms throughout the solar atmosphere.

For its second finding, IRIS observed numerous, small, low lying loops of solar material in the interface region for the first time. The unprecedented resolution provided by IRIS will enable scientists to better understand how the solar atmosphere is energized.

A surprise to researchers was the third finding of IRIS observations showing structures resembling mini-tornadoes occurring in solar active regions for the first time. These tornadoes move at speeds as fast as 12 miles per second and are scattered throughout the chromosphere, or the layer of the sun in the interface region just above the surface. These tornados provide a mechanism for transferring energy to power the million-degree temperatures in the corona.

Another finding uncovers evidence of high-speed jets at the root of the solar wind. The jets are fountains of plasma that shoot out of coronal holes, areas of less dense material in the solar atmosphere and are typically thought to be a source of the solar wind.

The final result highlights the effects of nanoflares throughout the corona. Large solar flares are initiated by a mechanism called magnetic reconnection, whereby magnetic field lines cross and explosively realign. These often send particles out into space at nearly the speed of light. Nanoflares are smaller versions that have long been thought to drive coronal heating. IRIS observations show high energy particles generated by individual nanoflare events impacting the chromosphere for the first time.

“This research really delivers on the promise of IRIS, which has been looking at a region of the sun with a level of detail that has never been done before,” said De Pontieu, IRIS science lead at Lockheed Martin in Palo Alto, California. “The results focus on a lot of things that have been puzzling for a long time and they also offer some complete surprises.”

IRIS is a Small Explorer mission managed by NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, in Greenbelt, Maryland for the agency’s Science Mission Directorate at NASA Headquarters. NASA’s Ames Research Center in Moffett Field, California, provides mission operations and ground data systems. The Norwegian Space Centre is providing regular downlinks of science data. Lockheed Martin designed the IRIS observatory and manages the mission for NASA. The Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics in Cambridge, Massachusetts, built the telescope. Montana State University in Bozeman designed the spectrograph. Other contributors for this mission include the University of Oslo and Stanford University in Stanford, California.

For more information about IRIS, visit:

-end-

Dwayne Brown

Headquarters, Washington

202-358-1726

dwayne.c.brown@nasa.gov