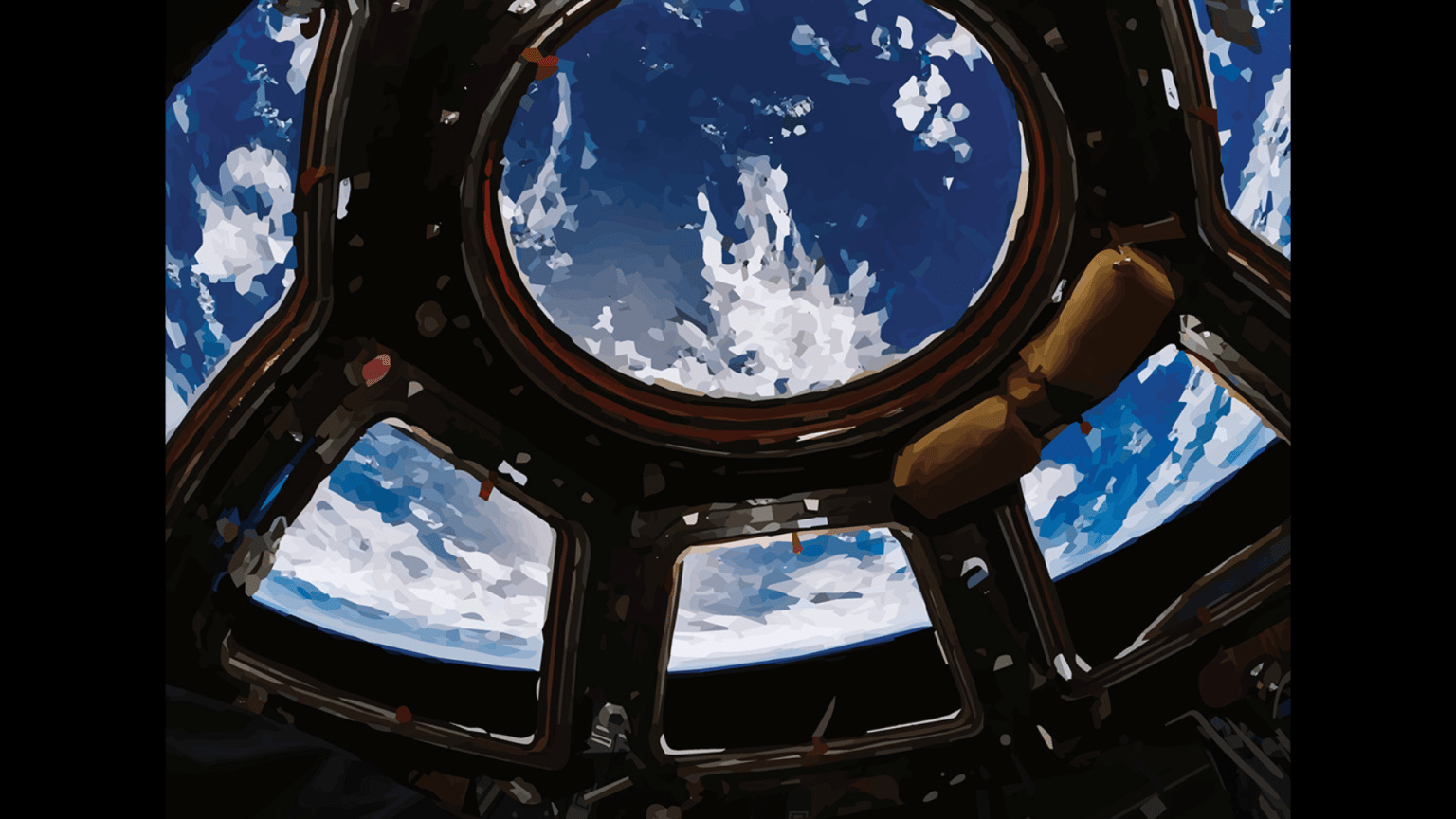

In addition to research into the physical health of astronauts, scientists also use the International Space Station and low-Earth orbit to investigate the psychological and behavioral impacts of long-duration missions in space.

Isolation and distance from Earth present unique challenges when choosing a crew for missions to the Moon and Mars. The farther and longer we travel in these restricted environments, the more care must go into crew selection and preparation. The dynamics associated with mission length and distance are crucial to mission success, with communication, morale, and understanding among crew members vital to this achievement. NASA’s Human Research Program (HRP) is investigating how a standardized assessment of behavioral health for space station crew can also help predict performance capabilities for future exploration crews once they land on the Moon or Mars.

Other examples of research into the behavioral health of crew members includes the following areas:

- Engaging in relevant, meaningful activities, including learning a language or learning new medical skills, have been found to help ward off depression and boost morale.

- HRP is examining the effects of tending to a space garden on the space station, which could have positive behavioral health benefits in addition to providing a fresh source of food and helping to purify the air.

- A collaborative CNES (French Space Agency) and ESA (European Space Agency) study, Immersive Exercise, tested whether a virtual reality environment for the station’s exercise bicycle increases motivation to exercise and provides astronauts and cosmonauts a better experience for their daily multi-hour training sessions.

- Researchers are using Earth-based analogs to investigate how much privacy and living space will be needed on longer missions where crew members will be restricted in a relatively small spacecraft together.

Using this space station research, scientists aim to ensure that future space explorers will not only survive but thrive on their spacefaring missions. However, the same research and experience can be applied to informing how we address social isolation on Earth. For example, when 33 Chilean miners were trapped underground for more than two months, NASA psychologists were part of a team deployed to help. Their experience in keeping crew mentally healthy in small, isolated spaces like the International Space Station helped rescuers support the miners in coping with their isolation, anticipate group dynamics, and manage any tensions that arose. The psychologists made recommendations for regular communications between the trapped minors and their families and provided counseling support for the families during the crisis and through the adjustment period as their loved ones returned home.