Lea la versión en español aquí.

By Jason Costa

NASA’s Kennedy Space Center

The longest – and perhaps the spiciest – plant experiment in the history of the International Space Station, Plant Habitat-04 (PH-04), concluded recently, 137 days after it began. On Nov. 26, Expedition 66 Flight Engineer Mark Vande Hei harvested and with other members of the crew sampled some of the 26 chile peppers grown from four plants in the orbiting laboratory’s Advanced Plant Habitat (APH), with PH-04 also breaking the record for feeding the most astronauts from a crop grown in space.

“PH-04 pushed the state-of-the-art in space crop production significantly,” said Matt Romeyn, principal investigator for PH-04 from NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida. “With this experiment, we took a field cultivar of a Hatch chile pepper from New Mexico, dwarfed it to fit inside the plant habitat, and figured out how to productively grow the first generally recognized fruiting crop in space – all in a span of a couple years.”

In June, a science carrier containing 48 sanitized pepper seeds launched to the space station. Expedition 65 crew member and NASA astronaut Shane Kimbrough, inserted the carriers into the facility and added water on July 12, starting the PH-04 experiment. Over the course of the experiment, the astronauts performed hands-on work, including removing all but four of the germinated plants, giving each plant enough room to grow, in a total area about the size of a large microwave oven.

The team at Kennedy monitored from the ground and controlled conditions inside the APH. Within several weeks, the plants flowered. The team ran the habitat’s fans at different speeds to disperse pollen, and astronauts performed some pollination by hand. These efforts soon led to fruit. Vande Hei picked the first crop of seven peppers on Oct. 29. The crew ate the first harvest, with NASA astronaut and Expedition 65 flight engineer Megan McArthur adding the peppers to a taco made using fajita beef, rehydrated tomatoes and artichokes. During the second harvest, Vande Hei prepared 12 peppers for return to Earth, and the crew ate the rest as part of taco night. Some members of the crew filled out surveys as part of the data collected, and provided feedback about the peppers.

“The level of excitement around the first harvest and the space tacos was unprecedented for us,” Romeyn said. “All indications are some of the fruit were on the spicier side, which is not unexpected, given the unknown effect microgravity could have on the capsaicin levels of peppers.”

Installed in the space station in 2018, the APH is an enclosed growth chamber with cameras and more than 180 sensors that are in constant interactive contact with a team at Kennedy. It joined NASA’s other orbital growth chamber, the Vegetable Production System, known as Veggie, which is about the size of a carry-on suitcase. Beginning with red romaine lettuce in 2014, Veggie has yielded a variety of plant harvests, including different types of lettuce, Chinese cabbage, mizuna mustard, red Russian kale, and zinnia flowers, as well as scientific research on cotton, algae, and several other experiments. Since 2015, astronauts have eaten nine types of leafy greens grown in Veggie, as well as two crops grown in APH – radishes and peppers.

Unlike Veggie, APH is automated. Although APH’s automation suggests less hands-on work is needed, the act of caring for the peppers illustrated the behavioral health improvements astronauts may experience when growing plants in space.

“The biggest benefit that I’ve seen personally is the impact growing plants has on the crew,” said Nicole Dufour, PH-04’s project manager. “They are so engaged when they are interacting with the plants, especially when it’s a crop plant like the peppers. We discovered the crew had been taking the door shade off every day to check on the plants and look at the peppers. That’s not something we asked them to do – they just wanted to because they enjoyed it so much.”

Despite the excitement generated by the presence of peppers, the team made several observations about plant growth that provide valuable insight to future crop production in microgravity.

“For the most part, the plants have grown similarly on the space station and on the ground, but there have been a few differences,” Romeyn said. “For one, the peppers are delayed by about two weeks on the space station. We think this is caused by a delay in germination, probably related to fluid challenges in microgravity. An interesting observation has been the pedicels – the stems – that connect to the flowers and fruit were not curved at all as seen on the ground, but instead were completely straight, which is definitely a microgravity effect.”

When the chile peppers return to Earth, the PH-04 team at Kennedy will focus on analyzing the data collected, as well as studying samples from the orbiting outpost. The results will help show the effect growing in microgravity had on the crop.

After the success of PH-04, the next planned edible crop experiments include growing dwarf tomatoes and testing new types of leafy greens. The team at Kennedy also has been laying the groundwork for growing microgreens, legumes, and herbs on the space station in the near future. The APH also has a cotton experiment planned, and Veggie will host other plant experiments before astronauts use it to grow more food they plan to eat.

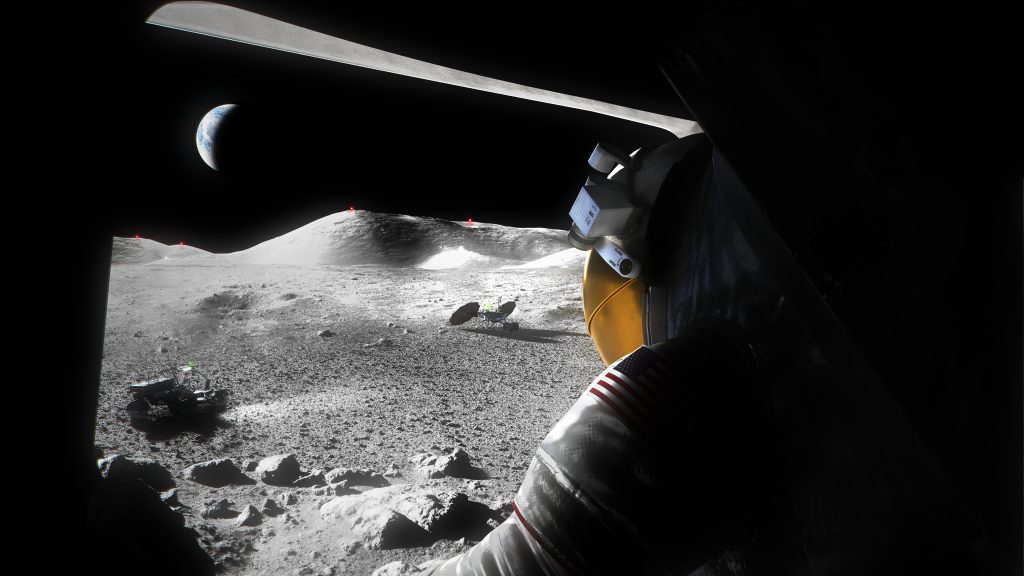

“We went into this experiment knowing it wouldn’t be easy to grow peppers in microgravity, but this experiment was a wildly successful demonstration that we’re on the right path for space crop production,” Romeyn said. “Veggie and APH are both great systems, and we pushed APH to the limits with these chiles. We plan to take lessons we’ve learned and continue to test and develop a much larger variety of plants for eventual integration into the crew diet. Our goal is to enable viable and sustainable crop production for future missions as people explore the Moon and Mars.”