The saying “more hands make light work” is rarely more apt than when those hands are 250 miles up on the International Space Station, overseeing research to extend humanity’s reach into the solar system and offer new scientific breakthroughs on Earth.

With the arrival on station of two new sets of hands — NASA astronauts Robert Behnken and Douglas Hurley, whose May 30 launch from U.S. soil on NASA’s SpaceX Demo-2 test flight was the first for American astronauts on American rockets to the space station since the space shuttle era ended — the Expedition 63 crew swelled to five. As a result, more crew time is available for research activities.

“Those extra hands are one reason NASA’s Commercial Crew Program is so important to research planners,” said Bryan Dansberry, space station associate program scientist at NASA’s Johnson Space Center in Houston. “Any business owner or homeowner understands a number of maintenance and cleaning tasks are required to keep things running smoothly. The more available hands, the more time you can spend doing the tasks that make your business successful. In our case, that means more science — conducting research in the unique laboratory that is the space station to conduct more experiments and technology demonstrations.”

During their stay, Behnken and Hurley have their own priority tasks — mainly continuing to test the Crew Dragon spacecraft in support of NASA’s Commercial Crew Program. But they’re also pitching in to help fellow NASA astronaut and Expedition 63 Commander Chris Cassidy and Russian cosmonauts Anatoly Ivanishin and Ivan Vagner support some 240 new and ongoing experiments during the latest station expedition, also called an increment.

That science tempo is the station’s hallmark, said Beau Simpson, payload operations manager in the Payload Operations Integration Center at NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama — the round-the-clock science hub linking global researchers to the astronauts overseeing their experiments on station.

What has really impressed the payload operations team at Marshall, Simpson said, is how Behnken and Hurley — trained exhaustively for Crew Dragon’s groundbreaking flight — have also hit the ground running with science on station. “These are seasoned pilots, sharp guys dedicated to NASA’s mission,” he said. “They got their space legs pretty quickly and jumped right into the mix.”

They even helped launch two new studies right off the bat. They’re both supporting the Electrolysis Measurement experiment, which studies how gravity influences electrolytic gas evolution. That electrochemical process generates bubbles that can help adjust pressure in devices such as skin patches used to deliver medication. Hurley also worked on the Capillary Structures investigation, which studies the management of fluid and gas mixtures for next-generation life support systems to better recycle water and remove carbon dioxide from cabin air on spacecraft. Behnken also is prepping the Plant Habitat-02 facility, an environmentally controlled chamber for the cultivation of edible plants — critical to future long-duration missions in space.

Integrating even industrious self-starters such as Behnken and Hurley into the science mix relies on months of work by planners at Marshall, space station leads at NASA’s Johnson Space Center and partner scientists around the world.

“Science scheduling and crew training starts six months out,” said Lori Meggs, lead payload communications manager at Marshall for Increment 63. That pace never slows. A week before each expedition starts, the payload planning team delivers final, step-by-step guidelines to walk the crew through each science activity.

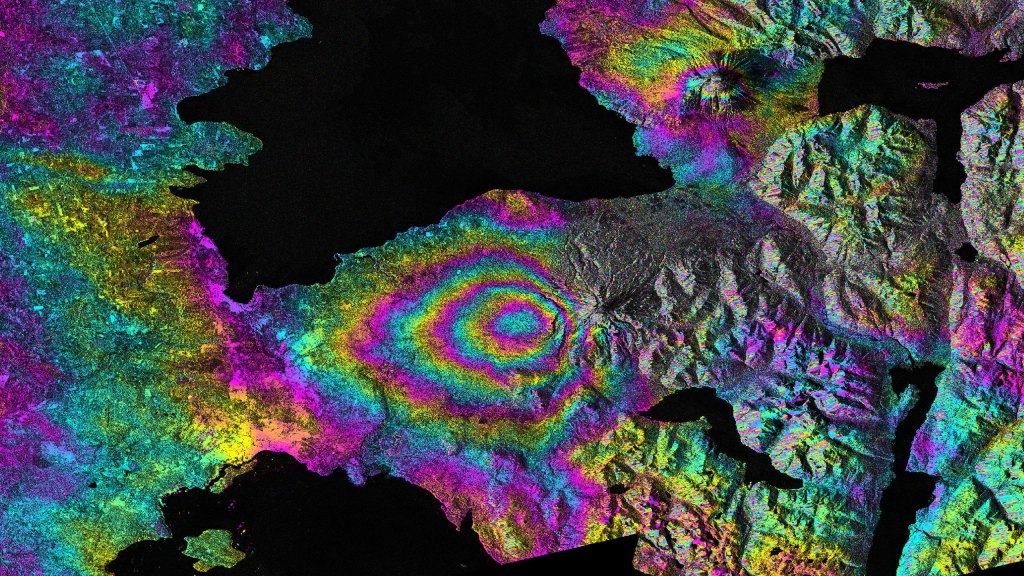

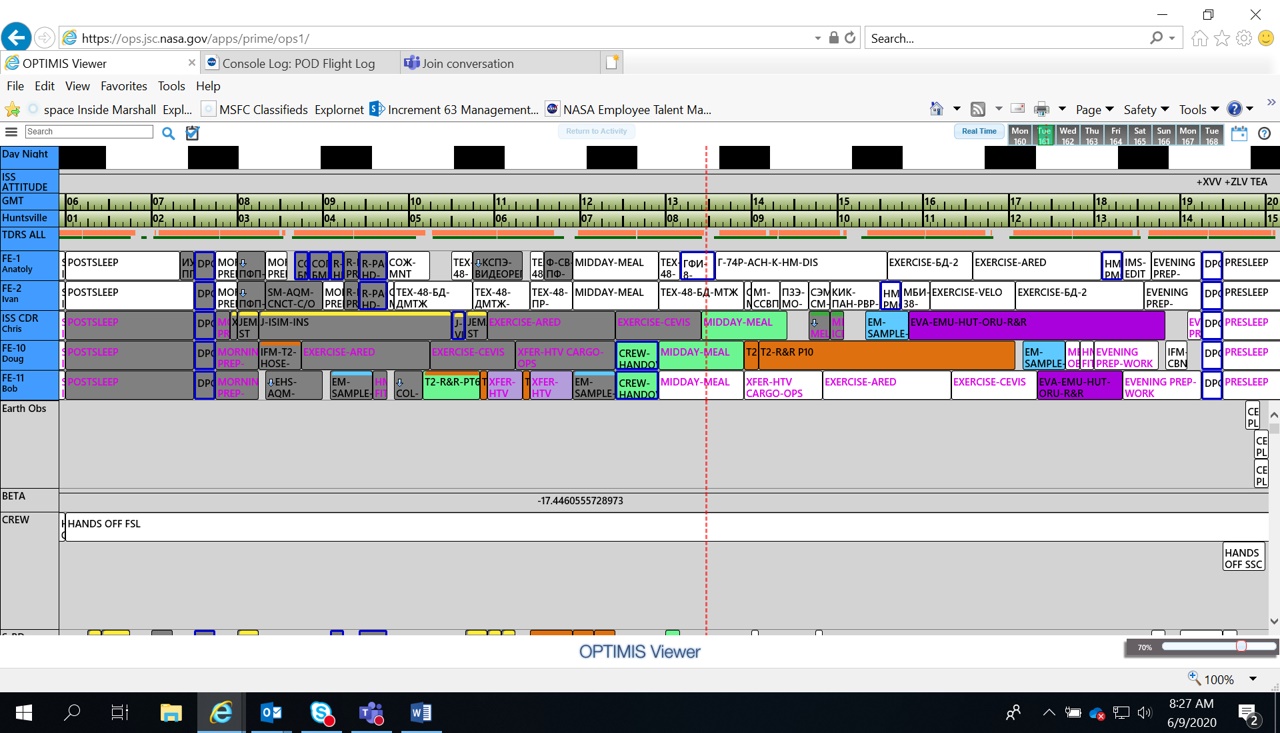

By then, station science planners also have used scheduling software — a real-time, interactive database that includes instructions for each experiment and task on station — to meticulously schedule the station crew’s research activities, exercise, personal time and sleep cycles.

The team also prepares for launch date slips caused by unforeseen contingencies — such as the weather that scrubbed the Dragon’s first launch attempt on May 27. “We had multiple backup schedules, based on possible delays of various lengths,” Simpson said. “Those backups took into account our plans for integrating the new arrivals into the mix. What tasks would the current crew need to handle if Bob and Doug were delayed?”

The schedule is key, Simpson said. Crew and flight controllers monitor it all day long, keeping an eye on the marching red bar which identifies where they should be at any moment. He calls that “chasing the red line” — and he credits the crew for consistently finishing tasks early, not chasing the line so much as challenging it to keep up.

Nor is finishing early a license to kick back, Meggs added. “They can use unscheduled time however they like, but we keep ‘honey-do’ lists, non-critical tasks that can be pursued any time. Whenever they finish scheduled work, each of them can choose duties from that list until it’s time for their next activity,” she said. “It’s a fun detour for them, and for us — seeing what items they choose from the list gives us insight into their interests and preferences.”

Each astronaut’s average schedule calls for six-and-a-half hours of scheduled science and maintenance tasks, two daily planning meetings with NASA and its global partners, two mandatory workout hours to mitigate the effects of microgravity on bones and muscles, and eight-and-a-half hours of time reserved for a good night’s sleep. Then they get up and do it all over again, for months on end.

“Our crew on station is so good,” Meggs said. “They’re having the time of their lives — and we’re living it with them. It’s a thrill to be part of the history they’re writing on orbit.”

Learn more about space station research here:

https://www.nasa.gov/mission_pages/station/research/benefits