By Jim Cawley

NASA’s Kennedy Space Center

An early challenge turned into a surprise success on the International Space Station that could be a boon for the future of space crop production.

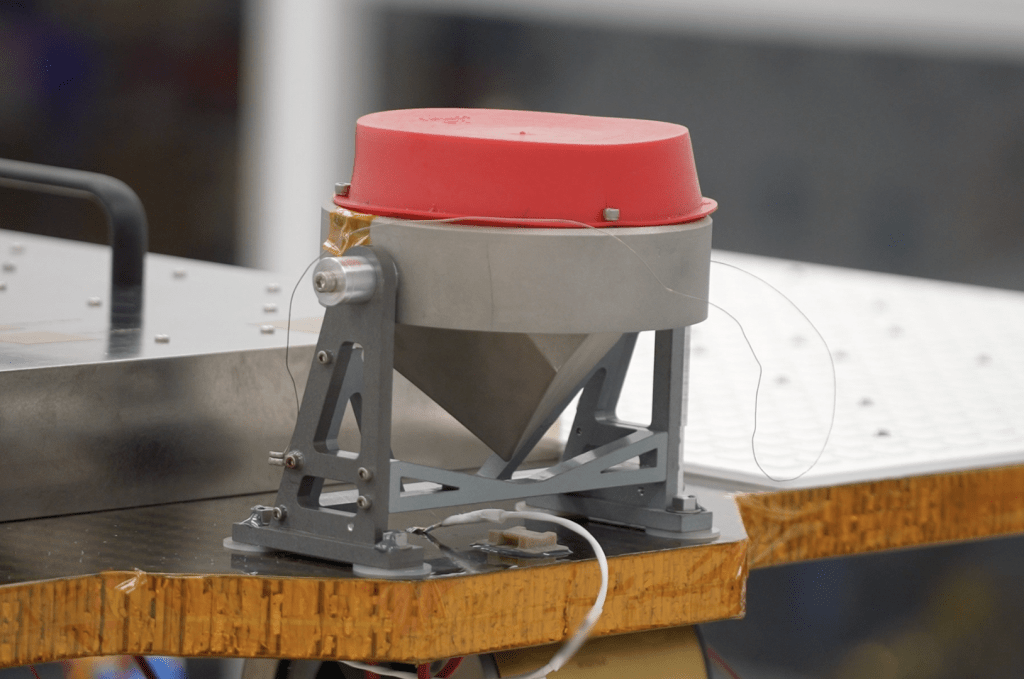

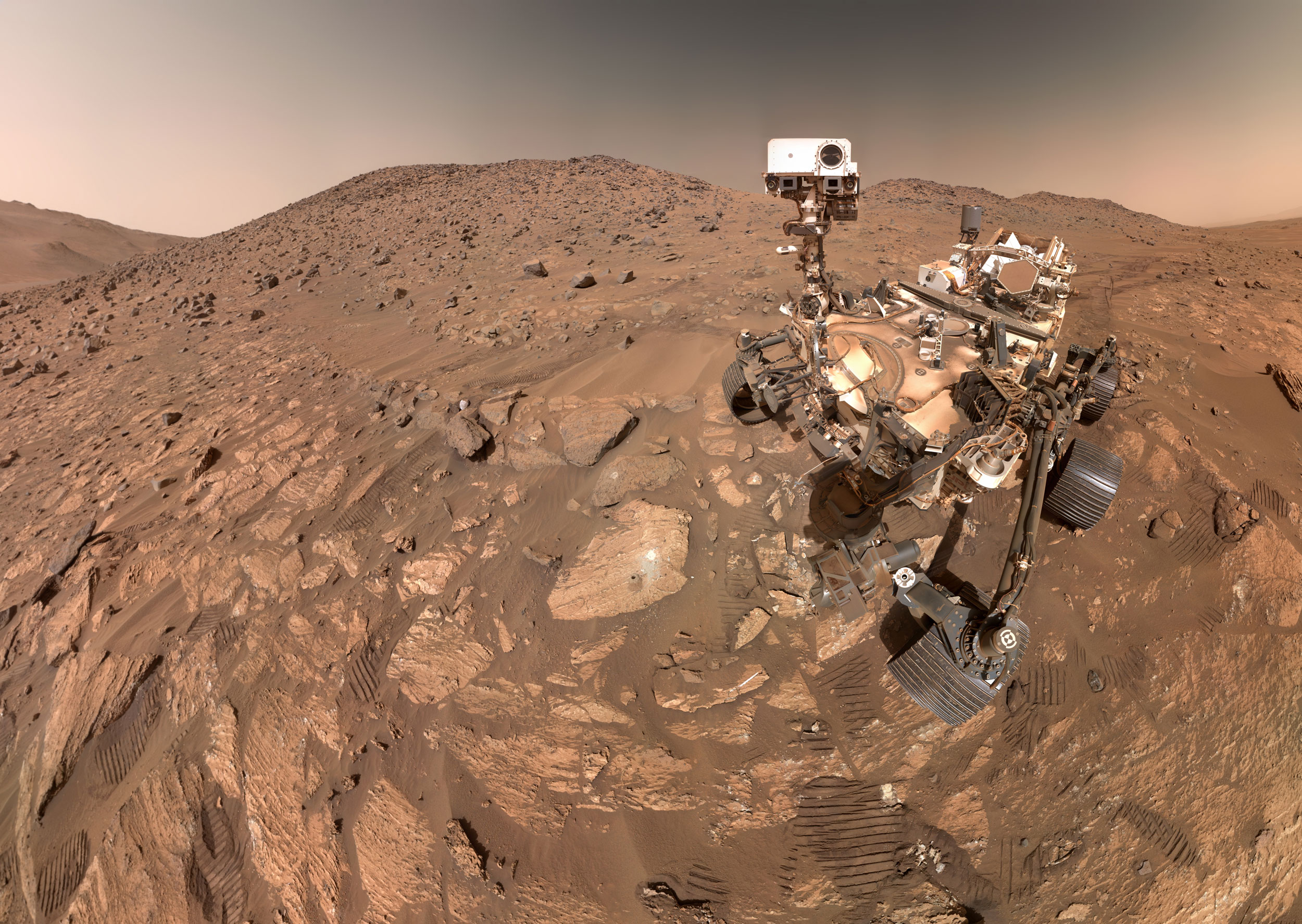

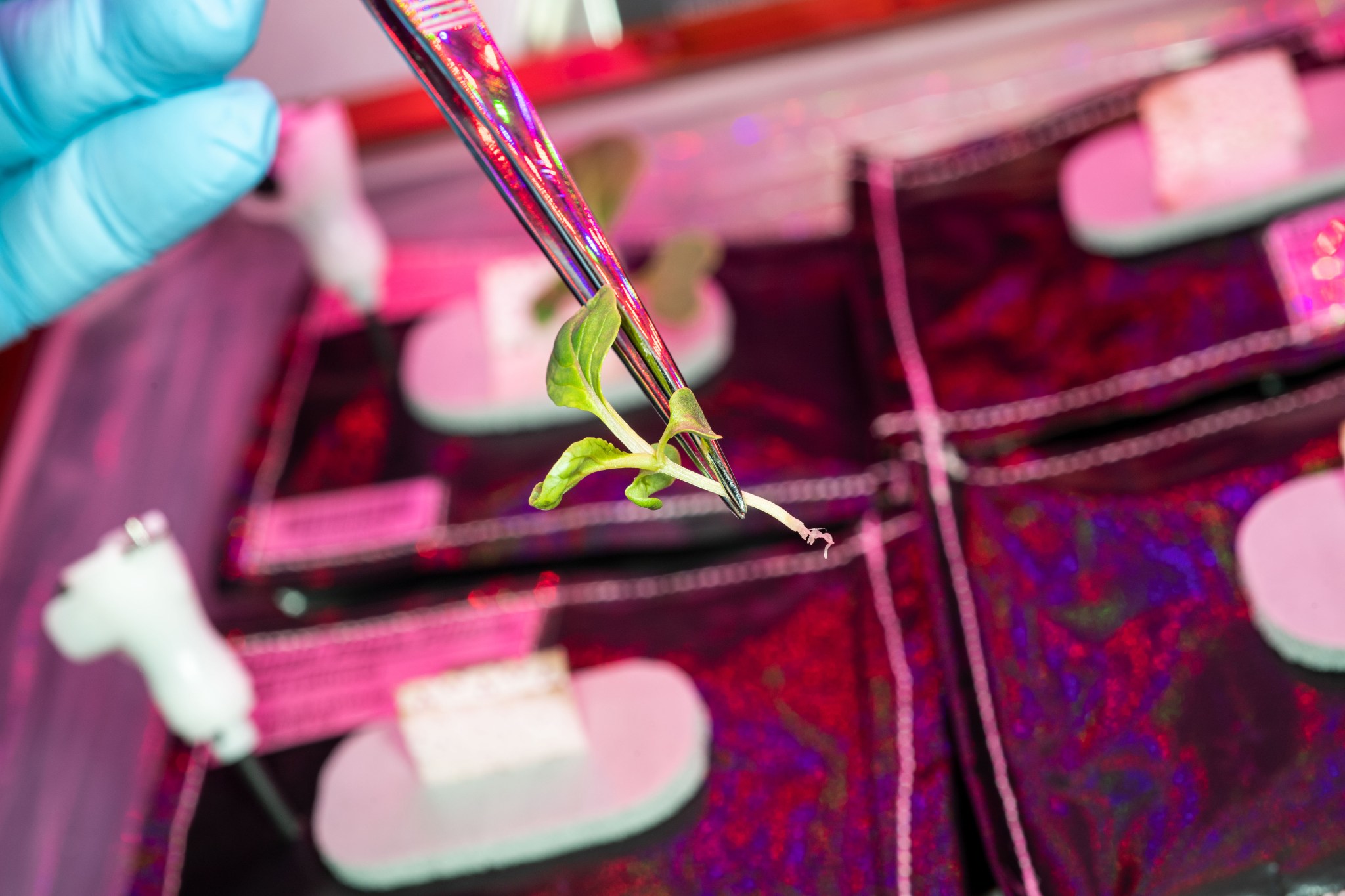

NASA astronaut Mike Hopkins recently noticed some plants failing to thrive aboard the station, so he executed the first plant transplant within the agency’s Vegetable Production System (Veggie). NASA researches crop production in space because plants can provide nutrients to astronaut crews on long-duration missions, such as a mission to Mars.

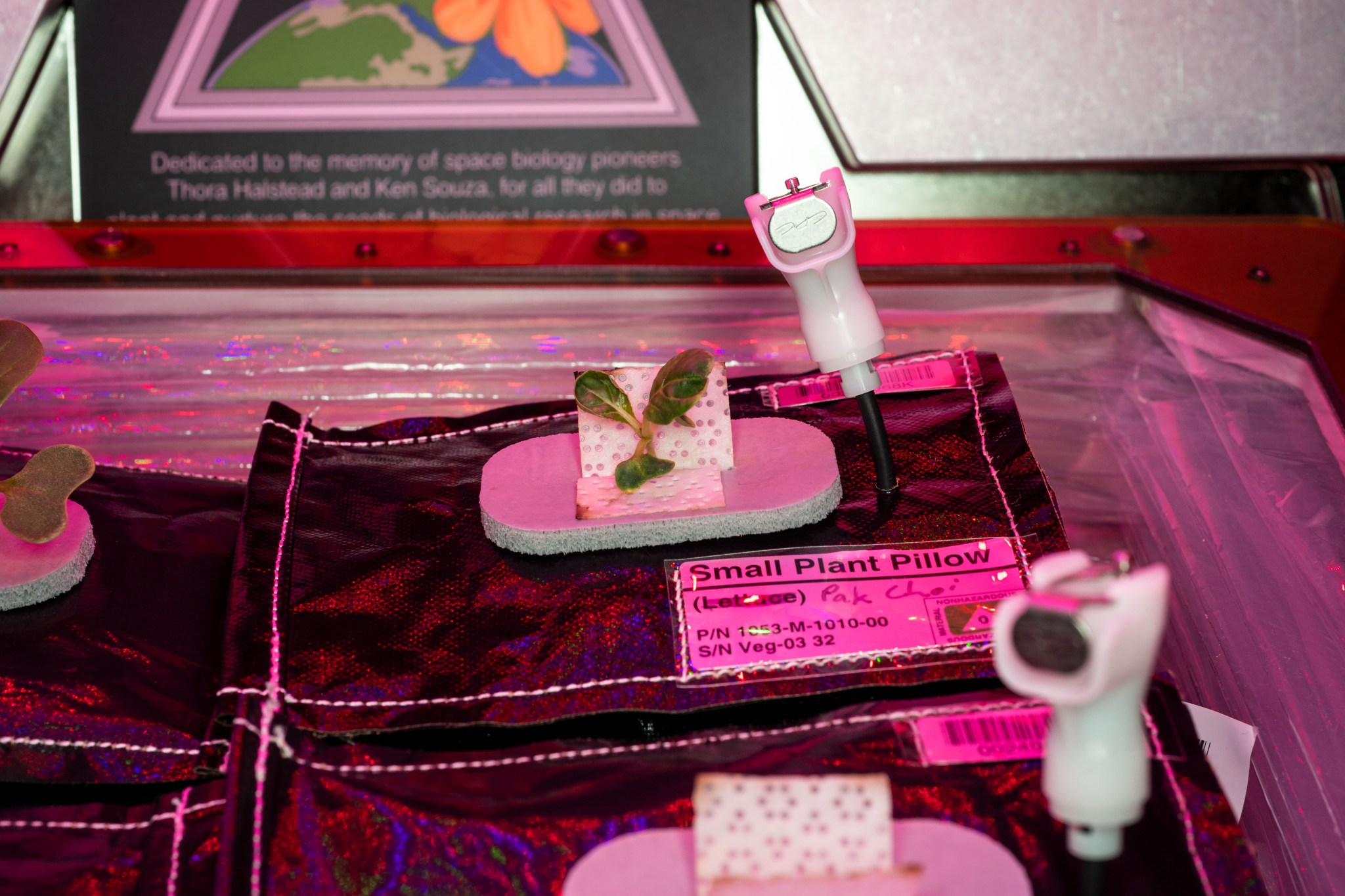

The Expedition 64 crew member, who arrived to the station for a six-month science mission aboard the SpaceX Crew-1 mission, was tending different varieties of mustards and lettuces in VEG-03I, one of two Veggie experiments currently growing in orbit. He noticed the mustards were growing fine in their special “pillows” containing clay-based growth media and fertilizer.

Some of the lettuces, however, were not. Two plant pillows containing ‘Outredgeous’ Red Romaine and ‘Dragoon’ lettuce seeds were germinating slowly, growing well behind the other plants. They would not catch up by harvest time.

On Jan. 14, with input from Veggie program scientists at Kennedy, the astronaut transplanted extra sprouts from the thriving plant pillows into two of the struggling pillows.

On Earth, this transplant technique is risky for plants in this delicate state, and NASA had never attempted it in a space experiment. But it worked. The transplants – ‘Red Russian’ kale and ‘Extra Dwarf’ pak choi – are surviving and growing along with the donor kale and pak choi. The remaining red romaine lettuce and “Wasabi” mustard in the experiment are also ready for harvest.

Although plant scientists at Kennedy don’t yet have a definitive answer about why some of the lettuce failed to grow as it did in previous experiments, they speculate that some seeds did not tolerate their long storage time as well. VEG-03I launched to station on June 29, 2018, aboard SpaceX’s 15th Commercial Resupply Services mission.

“This experiment is just really amazing; it shows the skill of the astronauts, the care that they take to do things, and also the differences that you see in microgravity,” Veggie Program Plant Scientist Gioia Massa said. “Fluids behave very differently in space than on the ground. The behavior of fluids – in this circumstance – seems to have helped the plants.”

Massa and Matt Romeyn, a space crop production project scientist and VEG-03I science lead, saw photos of Hopkins’ newly transplanted seedlings and had serious doubts about their survival due to the inevitable damage to the young roots. Predicting the plants likely would have died on Earth, the team was even more pessimistic about their survival in space.

“We’re used to microgravity working against us in the fluids/physics department, making growing plants in space very difficult,” Romeyn said. “So to have an exception like this, where microgravity appears to be helpful and the plants are growing better than on Earth … that’s astonishing.”

Romeyn said he did not expect this experiment would push the boundaries and show these results.

“This little accidental transplant success is going to be pretty important; it opens up a lot of areas for future development,” he said.

The ability to transplant crops creates flexibility for growing plants in space, as well as adding resiliency and redundancy for those times when something doesn’t go right, as it did early in this experiment. Massa said transplanting will be key in space where growing volume is at a premium. Transplanting will allow growth chambers to maximize available capacity when seeds fail to germinate and help ensure food security on a mission.

Hopkins is slated to harvest the crop on Feb. 2, and the astronauts plan to eat part of the harvest and send the rest back to Earth for study.

Though astronauts eat excellent, high-quality packaged foods, Massa pointed out that the vitamins in a packaged diet can break down and the quality decrease when stored for long periods of time.

“Right now, we are really focused on being able to grow a wide variety of crops that, when combined, provide the crew a lot of nutrients to help supplement this packaged diet,” Massa said. “To be sustainable, we have to be able to produce some of our food in space.”

Massa and Romeyn receive regular Veggie updates from Hopkins and other astronauts on station. They also are collecting data about how the plants affect the crew’s moods and well-being. Responses to date have been overwhelmingly positive.

“They all understand the importance of this work for long-duration exploration missions, where being able to produce food and being able to supplement the packaged diet with fresh produce is going to be absolutely critical from a safety and health point of view,” Massa said.

The Biological and Physical Sciences Division (BPS) of NASA’s Science Mission Directorate at NASA Headquarters in Washington is sponsoring the VEG-03I investigation as part of its mission to conduct research that enables human spaceflight exploration.