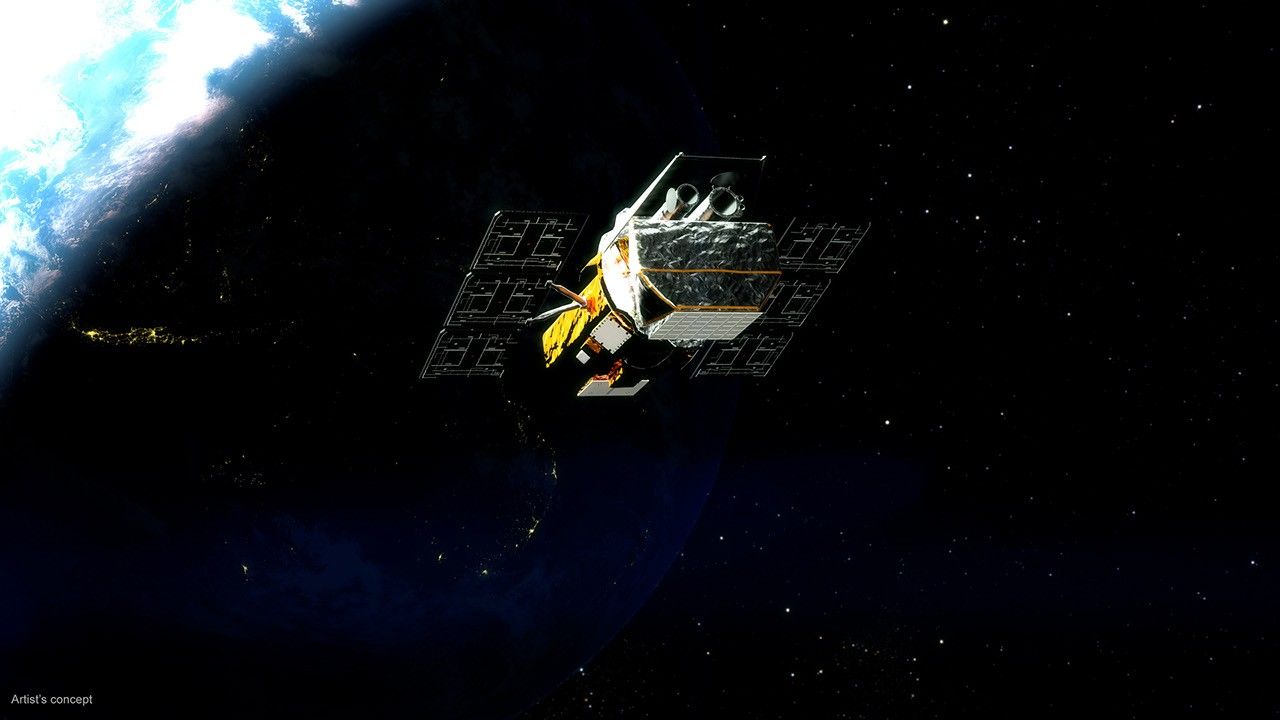

Paving the way for missions with astronauts, NASA’s Orion spacecraft will journey thousands of miles beyond the Moon during Artemis I to evaluate the spacecraft’s capabilities in what is called a Distant Retrograde Orbit (DRO). DRO provides a highly stable orbit where little fuel is required to stay for an extended trip in deep space to put Orion’s systems to the test in an environment far from Earth.

“Artemis I is a true stress test of the Orion spacecraft in the deep space environment,” said Mike Sarafin, Artemis Mission Manager. “Without crew aboard the first mission, DRO allows Orion to spend more time in deep space for a rigorous mission to ensure spacecraft systems, like guidance, navigation, communication, power, thermal control and others are ready to keep astronauts safe on future crewed missions.”

The orbit is “distant” in the sense that it’s at a high altitude from the surface of the Moon, and it’s “retrograde” because Orion will travel around the Moon opposite the direction the Moon travels around Earth. Orion will travel about 240,000 miles from Earth to the Moon, then about 40,000 miles beyond the Moon at its farthest point while flying in DRO.

DRO is highly stable because of its interactions with two points of the planet-moon system where objects tend to stay put, balanced between the gravitational pull of two large masses – in this case the Earth and Moon – which allows a spacecraft to reduce fuel consumption and remain in position while traveling around the Moon.

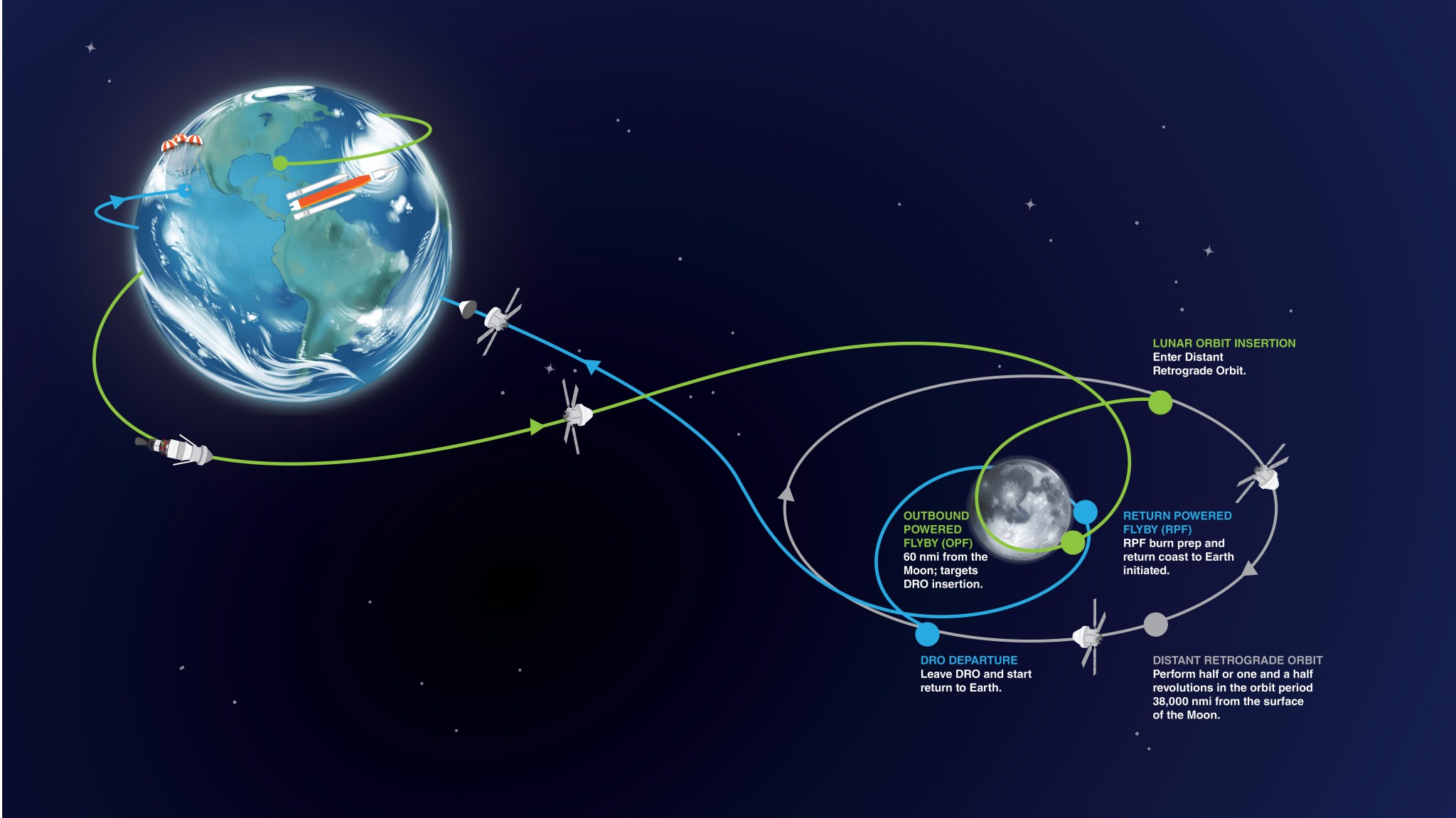

After the spacecraft gets its big push toward the Moon from the SLS rocket’s upper stage engine, Orion’s service module, built by ESA (European Space Agency), will provide the propulsion to get to DRO. Using the DRO for Artemis I requires the use of four major targeting navigational burns – two close and two far away from the Moon – to enter and exit the orbit. Orion will fly to its closest lunar approach about 60 miles above the surface of the Moon, then rely on the Moon’s gravitational force together with a propulsive burn – known as the outbound powered flyby – to direct the spacecraft toward DRO where Orion performs a second propulsive burn to enter DRO and stabilize in the orbit.

“Orion will spend about 6 to 19 days in DRO to collect data and allow mission controllers to assess the performance of the spacecraft,” said Nujoud Merancy, chief of the Exploration Mission Planning Office at NASA’s Johnson Space Center in Houston. “The exact duration of Orion’s stay in DRO is determined by when it launches due to orbital mechanics.”

For its return trip to Earth, Orion will perform a departure burn from DRO to direct itself to another close flyby within about 60 miles of the Moon’s surface. Another engine burn by the service module, known as the return powered flyby burn, and gravity assist from the Moon itself will slingshot Orion on a trajectory back home where the Earth will accelerate Orion to a speed of about 25,000 mph. This incredible speed will produce temperatures of approximately 5,000 degrees Fahrenheit – or about half the surface of the Sun – on the crew module during atmospheric entry, providing an opportunity to demonstrate Orion’s heat shield and parachute-assisted splashdown in the Pacific Ocean.

NASA first studied the DRO to support the proposed Asteroid Redirect Mission (ARM) which paralleled early SLS and Orion development. The plan for ARM was to capture a near Earth asteroid and redirect it to a lunar DRO. Because of the stability of the orbit, the asteroid could stay there for hundreds of years for research purposes without the need to use propulsion to maintain its orbit.

“NASA’s knowledge of DRO evolved out of many prior human spaceflight architecture studies,” said Merancy. “As a result of studies for ARM, NASA’s mission planners developed a strong knowledge base of the orbit and determined DRO could meet the objectives for Artemis I, so mission planners opted to capitalize on the studies and knowledge of it as a mission destination.”

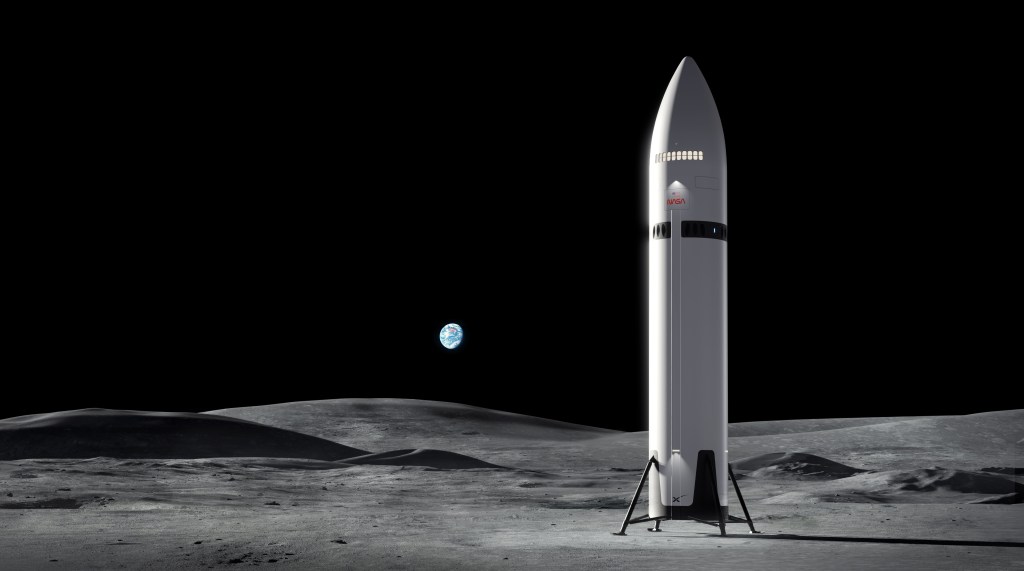

With Artemis, NASA will land the first woman and the first person of color on the Moon and establish long-term exploration in preparation for missions to Mars. SLS and Orion, along with the commercial human landing system and the Gateway that will orbit the Moon, are NASA’s backbone for deep space exploration.