NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope is back in business, exploring the universe near and far. The science instruments have returned to full operation, following recovery from a computer anomaly that suspended the telescope’s observations for more than a month.

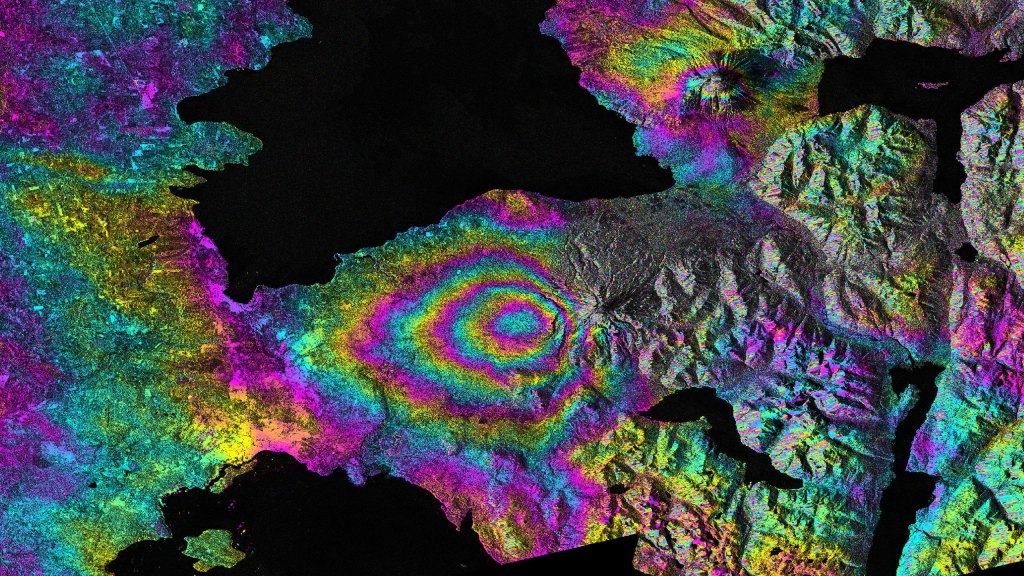

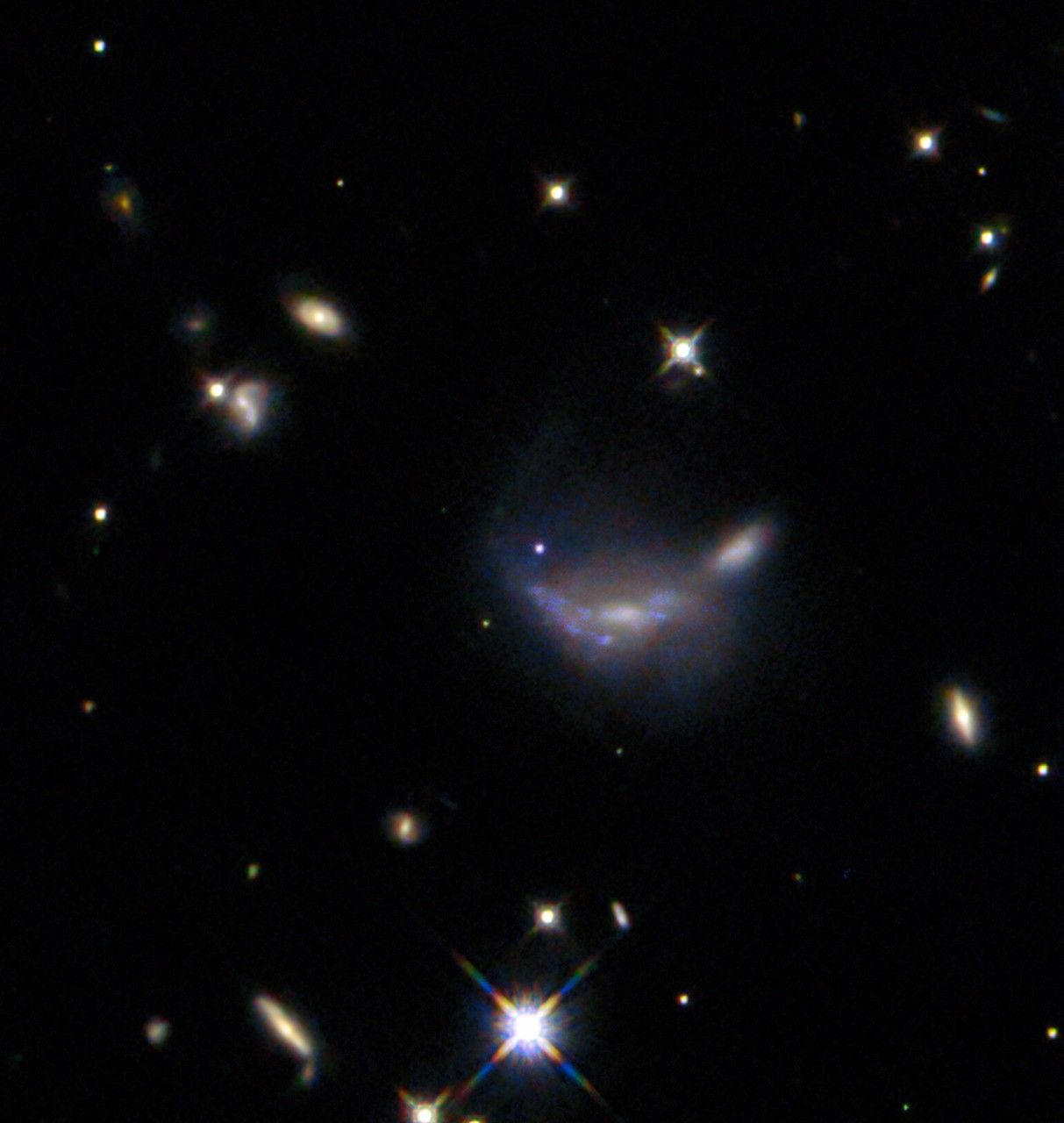

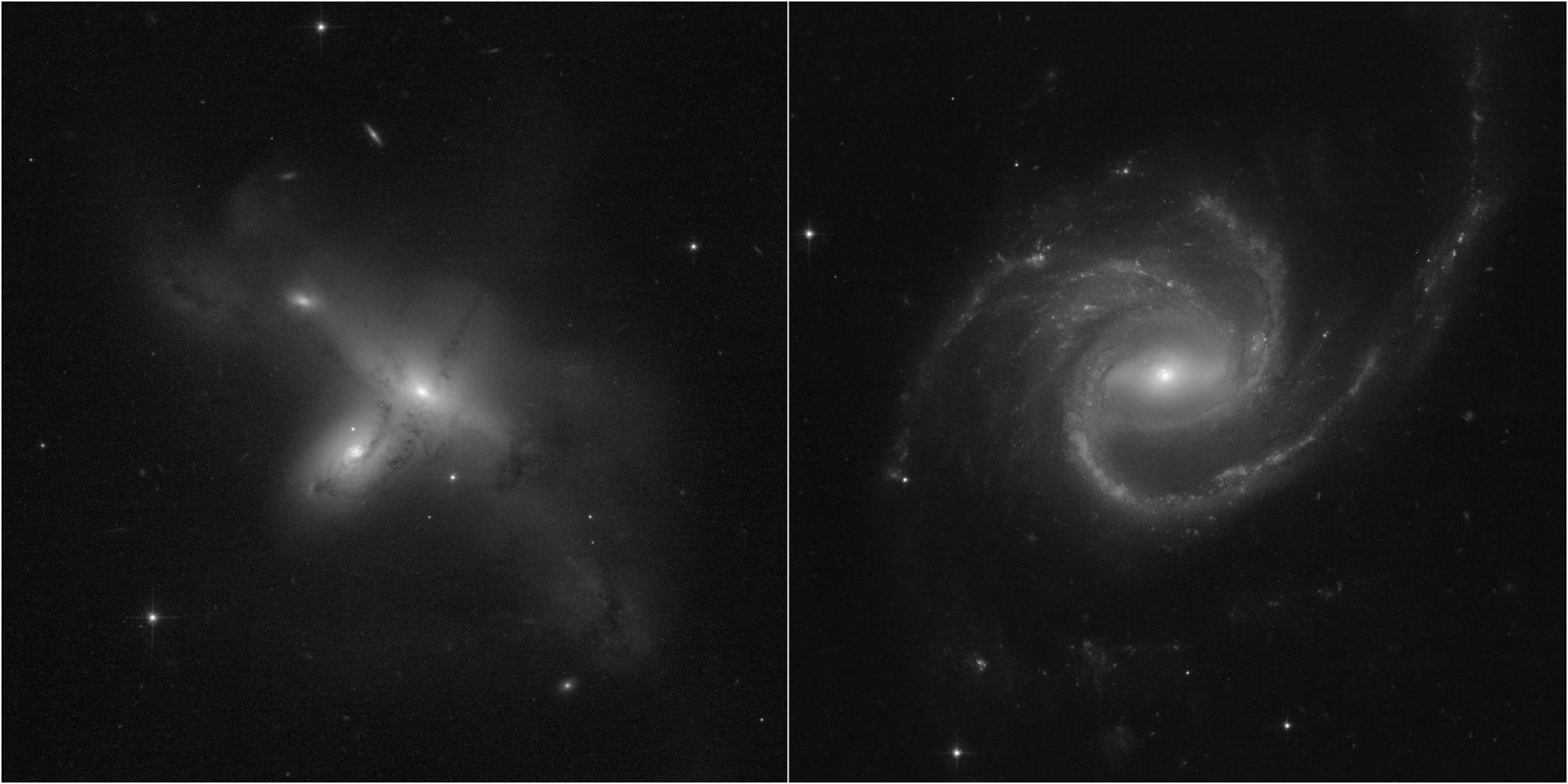

Science observations restarted the afternoon of Saturday, July 17. The telescope’s targets this past weekend included the unusual galaxies shown in the images above.

“I’m thrilled to see that Hubble has its eye back on the universe, once again capturing the kind of images that have intrigued and inspired us for decades,” said NASA Administrator Bill Nelson. “This is a moment to celebrate the success of a team truly dedicated to the mission. Through their efforts, Hubble will continue its 32nd year of discovery, and we will continue to learn from the observatory’s transformational vision.”

These snapshots, from a program led by Julianne Dalcanton of the University of Washington in Seattle, feature a galaxy with unusual extended spiral arms and the first high-resolution glimpse at an intriguing pair of colliding galaxies. Other initial targets for Hubble included globular star clusters and aurorae on the giant planet Jupiter.

Hubble’s payload computer, which controls and coordinates the observatory’s onboard science instruments, halted suddenly on June 13. When the main computer failed to receive a signal from the payload computer, it automatically placed Hubble’s science instruments into safe mode. That meant the telescope would no longer be doing science while mission specialists analyzed the situation.

The Hubble team moved quickly to investigate what ailed the observatory, which orbits about 340 miles (547 kilometers) above Earth. Working from mission control at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, as well as remotely due to COVID-19 restrictions, engineers collaborated to figure out the cause of the problem.

Complicating matters, Hubble was launched in 1990 and has been observing the universe for over 31 years. To fix a telescope built in the 1980s, the team had to draw on the knowledge of staff from across its lengthy history.

Hubble alumni returned to support the current team in the recovery effort, lending decades of mission expertise. Retired staff who helped build the telescope, for example, knew the ins and outs of the Science Instrument and Command & Data Handling unit, where the payload computer resides – critical expertise for determining next steps for recovery. Other former team members lent a hand by scouring Hubble’s original paperwork, surfacing 30- to 40-year-old documents that would help the team chart a path forward.

“That’s one of the benefits of a program that’s been running for over 30 years: the incredible amount of experience and expertise,” said Nzinga Tull, Hubble systems anomaly response manager at Goddard. “It’s been humbling and inspiring to engage with both the current team and those who have moved on to other projects. There’s so much dedication to their fellow Hubble teammates, the observatory, and the science Hubble is famous for.”

Together, team members new and old worked their way through the list of likely culprits, seeking to isolate the issue to ensure they have a full inventory for the future of which hardware is still working.

At first, the team thought the likeliest problem was a degrading memory module, but switching to backup modules failed to resolve the issue. The team then designed and ran tests, which involved turning on Hubble’s backup payload computer for the first time in space, to determine whether two other components could be responsible: the Standard Interface hardware, which bridges communications between the computer’s Central Processing Module and other components, or the Central Processing Module itself. Turning on the backup computer did not work, however, eliminating these possibilities as well.

The team then moved on to explore whether other hardware was at fault, including the Command Unit/Science Data Formatter and the Power Control Unit, which is designed to ensure a steady voltage supply to the payload computer’s hardware. However, it would be more complicated to address either of these issues, and riskier for the telescope in general. Switching to these components’ backup units would require switching several other hardware boxes as well.

“The switch required 15 hours of spacecraft commanding from the ground. The main computer had to be turned off, and a backup safe mode computer temporarily took over the spacecraft. Several boxes also had to be powered on that were never turned on before in space, and other hardware needed their interfaces switched,” said Jim Jeletic, Hubble deputy project manager at Goddard. “There was no reason to believe that all of this wouldn’t work, but it’s the team’s job to be nervous and think of everything that could go wrong and how we might compensate for it. The team meticulously planned and tested every small step on the ground to make sure they got it right.”

The team proceeded carefully and systematically from there. Over the following two weeks, more than 50 people worked to review, update, and vet the procedures to switch to backup hardware, testing them on a high-fidelity simulator and holding a formal review of the proposed plan.

Simultaneously, the team analyzed the data from their earlier tests, and their findings pointed to the Power Control Unit as the possible cause of the issue. On July 15, they made the planned switch to the backup side of the Science Instrument and Command & Data Handling unit, which contains the backup Power Control Unit.

Victory came around 11:30 p.m. EDT July 15, when the team determined the switch was successful. The science instruments were then brought to operational status, and Hubble began taking scientific data once again on July 17. Most observations missed while science operations were suspended will be rescheduled.

This is not the first time Hubble has had to rely on backup hardware. The team performed a similar switch in 2008, returning Hubble to normal operations after another part of the Science Instrument and Command & Data Handling (SI C&DH) unit failed. Hubble’s final servicing mission in 2009 – a much-needed tune-up championed by former U.S. Senator Barbara Mikulski – then replaced the entire SI C&DH unit, greatly extending Hubble’s operational lifetime.

Since that servicing mission, Hubble has taken more than 600,000 observations, bringing its lifetime total to more than 1.5 million. Those observations continue to change our understanding of the universe.

“Hubble is in good hands. The Hubble team has once again shown its resiliency and prowess in addressing the inevitable anomalies that arise from operating the world’s most famous telescope in the harshness of space,” said Kenneth Sembach, director of the Space Telescope Science Institute (STScI) in Baltimore, Maryland, which conducts Hubble science operations. “I am impressed by the team’s dedication and common purpose over the past month to return Hubble to service. Now that Hubble is once again providing unprecedented views of the universe, I fully expect it will continue to astound us with many more scientific discoveries ahead.”

Hubble has contributed to some of the most significant discoveries of our cosmos, including the accelerating expansion of the universe, the evolution of galaxies over time, and the first atmospheric studies of planets beyond our solar system. Its mission was to spend at least 15 years probing the farthest and faintest reaches of the cosmos, and it continues to far exceed this goal.

“The sheer volume of record-breaking science Hubble has delivered is staggering,” said Thomas Zurbuchen, associate administrator of NASA’s Science Mission Directorate. “We have so much to learn from this next chapter of Hubble’s life – on its own, and together with the capabilities of other NASA observatories. I couldn’t be more excited about what the Hubble team has achieved over the past few weeks. They’ve met the challenges of this process head on, ensuring that Hubble’s days of exploration are far from over.”

For more information about the first science images taken with Hubble following its return to science operations: https://hubblesite.org/contents/news-releases/2021/news-2021-045

For more information about Hubble, visit: www.nasa.gov/hubble

Experts and members of the Hubble team are available for interviews. For media inquiries, contact:

Claire Andreoli

NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, Md.

301-286-1940

claire.andreoli@nasa.gov

Alise Fisher

NASA Headquarters

202-617-4977

alise.m.fisher@nasa.gov

Elizabeth Landau

NASA Headquarters, Washington, D.C.

202-358-0845

elizabeth.r.landau@nasa.gov

Rob Gutro

NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, Md.

443-858-1779

robert.j.gutro@nasa.gov