Violent and destructive, active volcanoes ought to be feared and avoided. Yet, these geological cauldrons expose the pulse of many planets and moons, offering clues to how these bodies evolved from chemical soups to the complex systems of gases and rocks we see today.

Unearthing these clues is what motivates planetary scientists from NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, to venture to inhospitable places on this planet that most people try to avoid: smoldering lava fields and glacier-covered volcanoes.

“You can use Earth science to study volcanoes on this planet and then apply that knowledge to the Moon, Mars and other bodies,” said Patrick L. Whelley, a Goddard planetary geologist. “Plus, we don’t have the luxury of watching volcanic eruptions up close anywhere besides Earth.”

What’s clear about volcanoes on this planet is that Earth would have been desolate without them. By belching molten rock onto its surface from deep inside, these underground furnaces helped build Earth’s continents. Moreover, they released gases that helped form our oceans and our atmosphere billions of years ago — two features that enabled life to thrive here. To this day, volcanoes help keep Earth warm, wet and habitable.

Could volcanoes have played a similar role on other celestial bodies? Do they still?

These are some of the questions Whelley and his colleagues are trying to answer by studying the composition and geometry of Earth’s volcanoes and the lava they spew. The better we understand Earth, they reason, the sharper the rest of the solar system will come into focus.

Credits: Molly Wasser / NASA Goddard

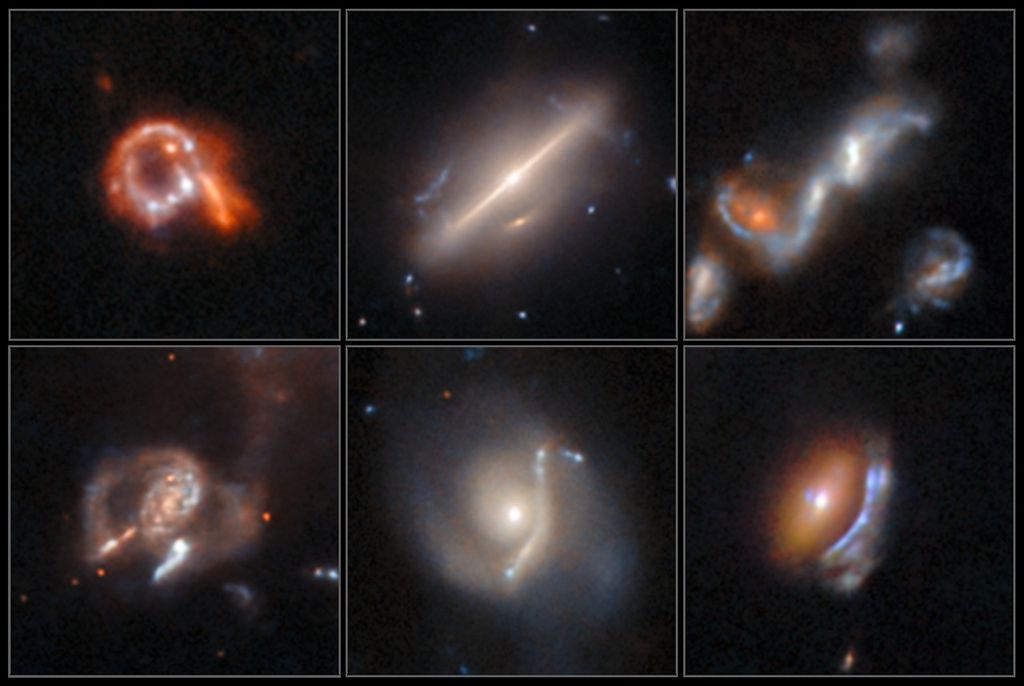

Evidence abounds that volcanoes dot the solar system. The dark patches on the Moon, where volcanoes are inactive, are made of lava that hardened billions of years ago. Mars boasts the solar system’s largest (though, now, likely inactive) volcanoes. Mercury hosts remnants of volcanoes that lost steam billions of years ago; Venus does, too, though its volcanoes could be active today.

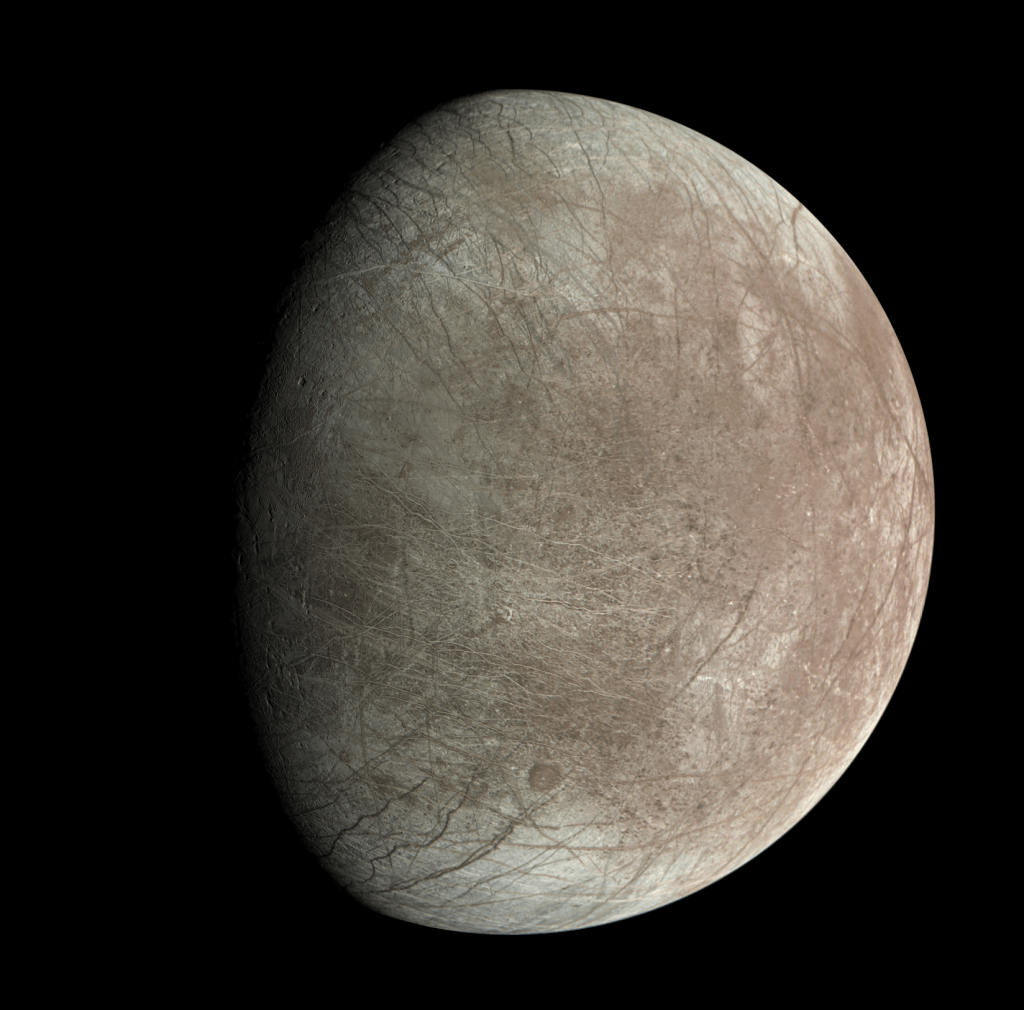

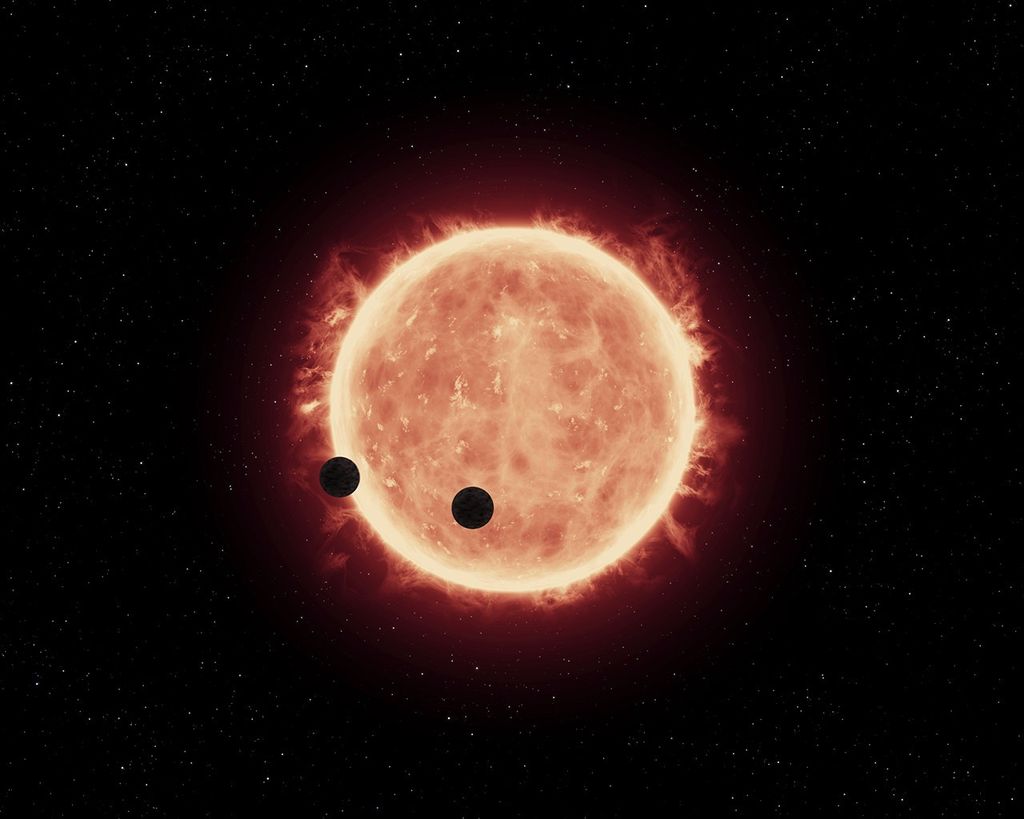

Some solar system volcanoes, besides our own, are clearly erupting. Jupiter’s moon, Io, is a volcanic wonderland, with hundreds of active plumes. Europa, another Jovian moon, appears to have active vents shooting water vapor through cracks in the shell of ice enveloping the moon.

In fact, Europa is an intriguing case. Scientists believe that it’s one of the strongest candidates for extraterrestrial life because it harbors a liquid water ocean — or a lubricant for life’s most essential processes — that could be rife with sulfur and other elements that living things need. Europa’s ocean is possibly up to twice as large as Earth’s in volume. Scientists hope to study Europa more closely in coming years by sending a spacecraft, called Europa Clipper, to study the cracked moon from the orbit of Jupiter.

Some scientists also hope to send a lander to probe the ice on Europa in search of chemical clues, called biosignatures, that could reveal whether the moon could harbor life.

But first, they must practice looking for life in remote and harsh regions of Earth. Goddard researchers did so this summer by traveling to a location in Iceland that’s the closest we can ever get on Earth to replicating Europa, trekking for miles to a glacier-covered volcanic region called Vatnajökull.

“These types of icy environments are rare, so they’re very fascinating,” said Dina Bower, a Goddard astrobiologist. Vatnajökull, she explained, offers scientists a rare opportunity to observe the chemistry that unfolds when geothermal heat interacts with ice, like it does on Europa.

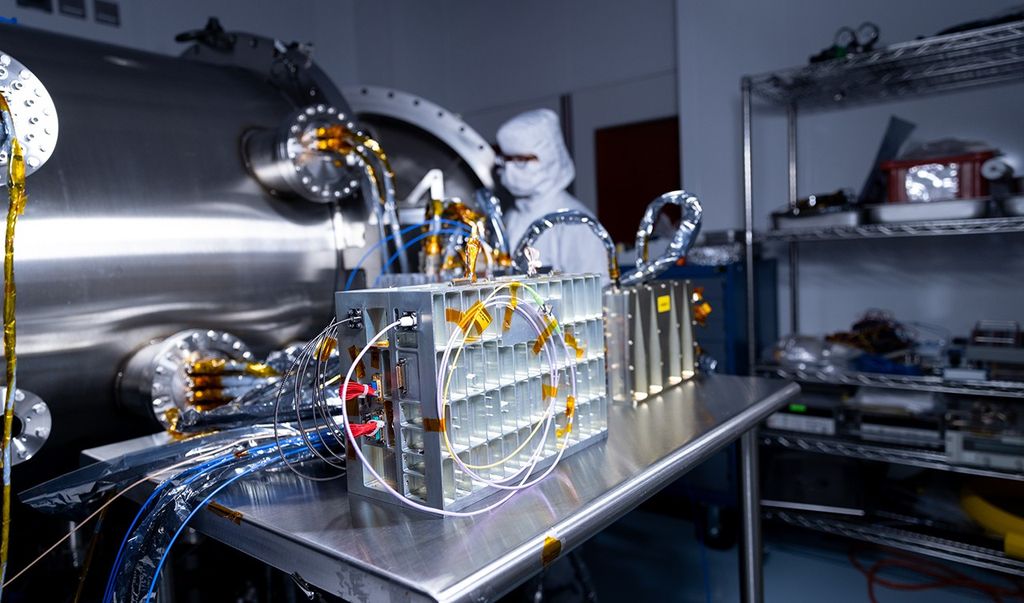

Bower tested a technique in Iceland called “Raman spectroscopy,” using a handheld instrument that resembles a price scanner to measure the scattering of light from ice to learn what the surface is made of. A similar technique could someday help spacecraft at Europa identify chemical signatures of life in its ice and ocean. For now, Bower’s Raman spectrometer found lichen, which are communities of fungi and other microbes, living in the ice, likely deposited there by volcanic ash. She also found various species of this hardy organism thriving on the lava.

Lava is also of interest for Goddard scientists, so it helps that Iceland is a lava paradise. Indeed, the island was composed in the last 15 to 20 million years of hardened lava from continual volcanic eruptions. This makes the island a good proxy for planets like Mars, too, which, like Iceland, are covered in a volcanic rock called basalt.

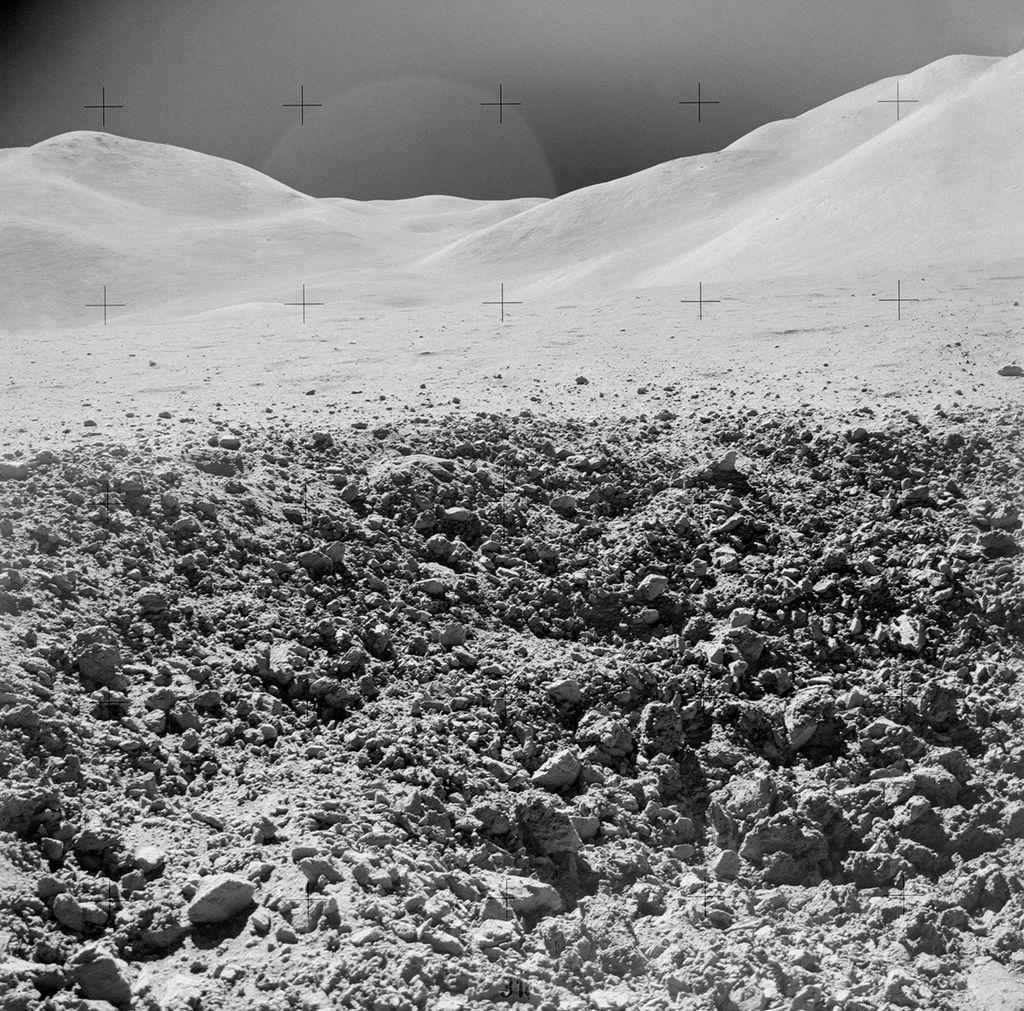

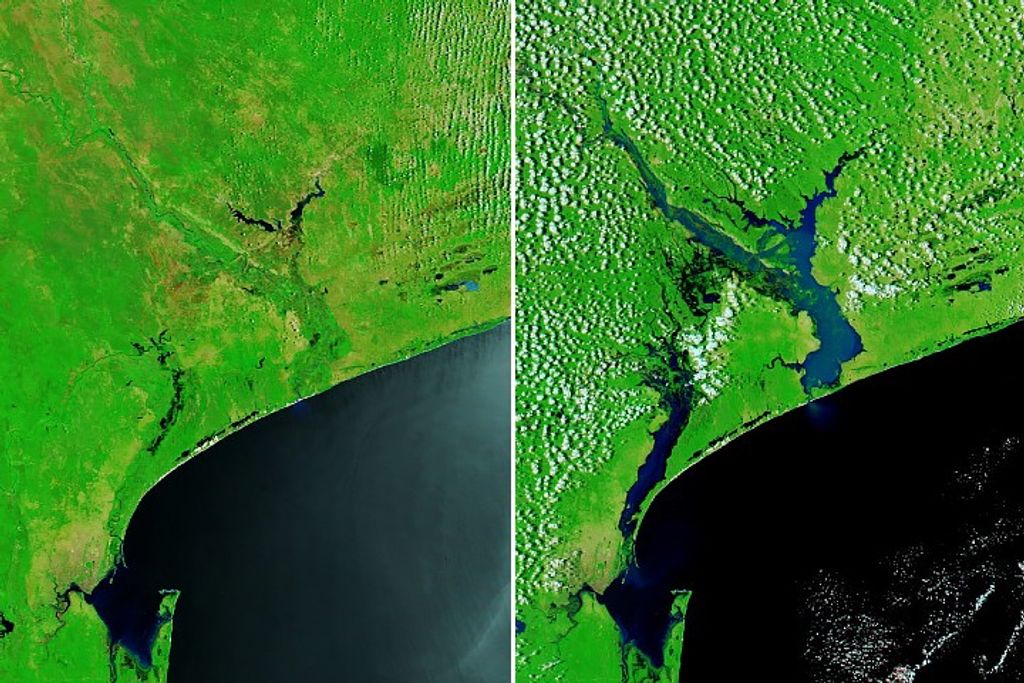

In Iceland, Goddard planetary geologists also visited the highlands region, near Vatnajökull, to investigate a large, fresh lava field called Holuhraun. Lava erupted from fissures in the ground there and flowed across 85 square kilometers (53 square miles) in a historic eruption between 2014 and 2015. Now, in their third visit to the main eruption vent in Holuhraun, planetary geologists sought to document how the terrain had changed since their last visit.

“The vent is still degrading in spectacular fashion” said Jacob Richardson, a Goddard planetary geologist, alluding to the active rockfalls off the vent walls. “This erosion is a sign that volcanic vents take more than just a couple of years to settle down; they might take decades.”

Whelley, Richardson and their team measured how much heat the lava is still releasing and how the hardening lava is changing the local landscape, information that will provide context for future observations of existing or old volcanoes on various celestial bodies.

“We rarely get to see fresh deposits anywhere in the solar system; we’re always looking at billion-year-old lava,” said Whelley. “But if you can tell how much heat there was in any given eruption throughout a planet’s history, you might be able to determine the rate at which the planet was getting rid of heat. This, in turn, will tell us how long it was producing volcanic eruptions that were releasing gases that were maintaining its atmosphere, which enabled conditions for life on the planet.”

Even if Mars never had conditions suitable for life on its surface, despite volcanic eruptions, life could have flourished beneath, NASA scientists suspect. Below the surface of Mars there could be water, plus protection from harsh solar radiation, and heat from nearby magma chambers, said Richardson.

“If you only look at the surface rock that we can see today, you’ll lose a lot of the story of how these planets evolved,” he said.

This is why NASA will drop its InSight lander on the surface of Mars on November 26, 2018 to listen for tremors on Elysium Planitia, a volcanic field similar to Holuhraun, to study the planet’s crust, mantle, and core.

In the meantime, Goddard scientists will continue hunting for secrets of the evolution of our home planet and its inhabitants — an ideal laboratory for studying the cosmos.

By Lonnie Shekhtman

NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, Md.