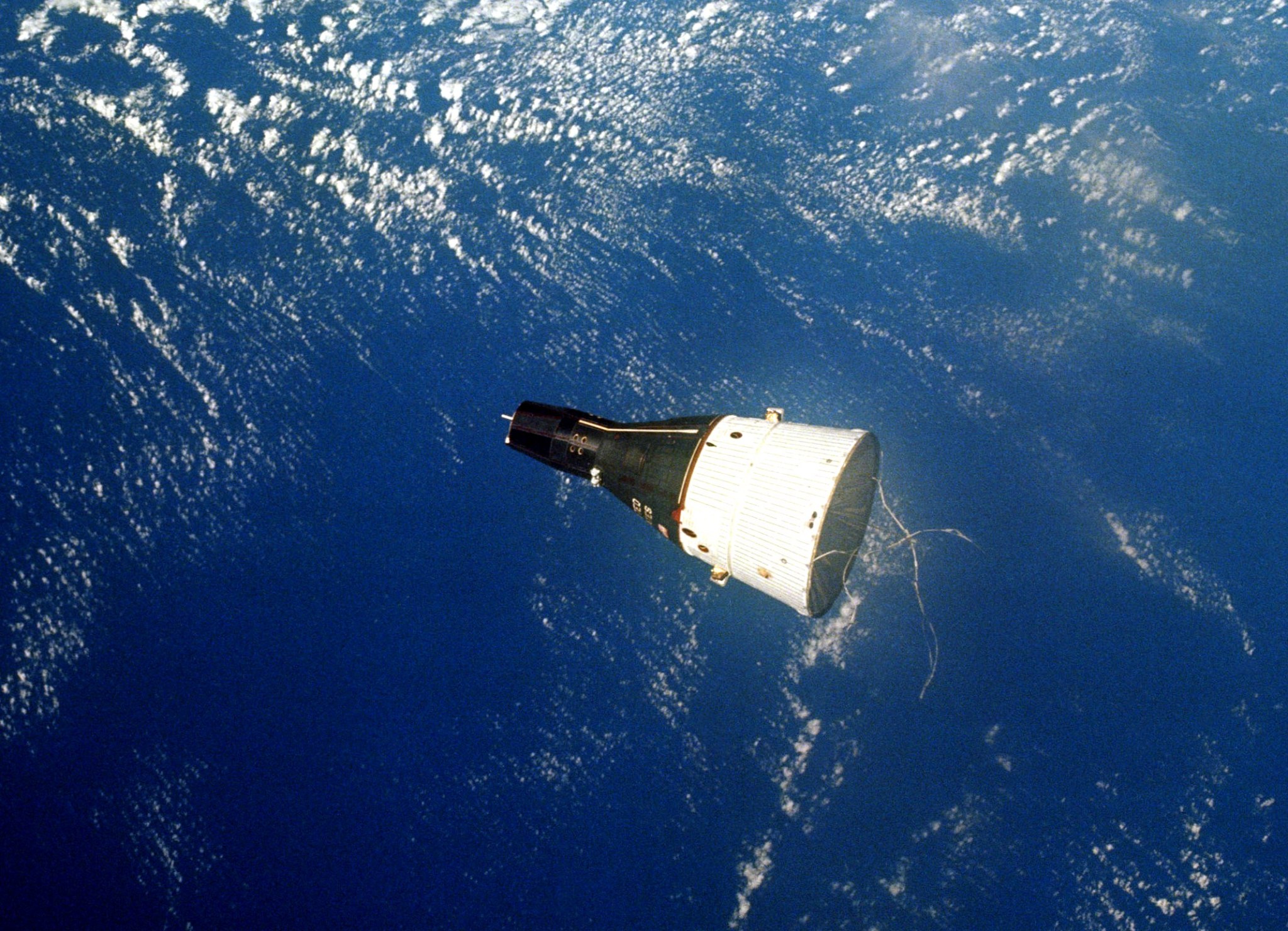

The flights of two piloted spacecraft during December 1965 were major strides forward in advancing NASA’s capabilities in human spaceflight. They also marked the point in which the United States clearly pulled ahead in the space race with the Soviet Union.

While Gemini VII orbited the Earth for two weeks, Gemini VI was launched, completing the first-ever rendezvous between two spacecraft in orbit. It was a transformative capability that was not only necessary for the Apollo moon landing missions, but crucial in building and operating the International Space Station. The rendezvous marked the first time a human spaceflight milestone was achieved by the United States first.

Although the Soviet Union twice had launched simultaneous pairs of Vostok spacecraft in 1962 and 1963, the cosmonauts only established radio contact, coming no closer than several miles of each other.

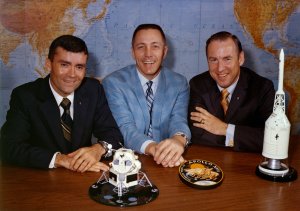

The original plan for Gemini VI was to launch an unpiloted Agena upper stage atop an Atlas rocket on Oct. 25, 1965. As the target vehicle completed its first orbit, a Titan II launch vehicle was to lift off with astronauts Wally Schirra and Tom Stafford aboard. Gemini VI then would rendezvous and dock with the Agena.

After the Atlas rocket lifted off, the Agena’s secondary engines fired to separate it from the launch vehicle. However, immediately after the Agena’s primary engine fired, telemetry was lost and the target vehicle failed to reach orbit. The launch of Gemini VI was postponed.

Schirra was a member of the original seven astronauts having flown Mercury 8 for six orbits on Oct. 3, 1962. He would go on to command the first piloted Apollo mission in October 1968, becoming the only astronaut to fly in Mercury, Gemini and Apollo.

Stafford was one of nine pilots selected in NASA’s second group of astronauts. He would serve as commander for Gemini IX in 1966, and Apollo 10, the lunar landing rehearsal mission, in 1969. He also commanded the crew of the American spacecraft that linked up with two Soviet cosmonauts as part of the Apollo-Soyuz Test Project in 1975.

Since the next Agena target vehicle would not be ready for several months, a new plan began to take shape for Schirra and Stafford.

According to “On the Shoulders of Titans: A History of Project Gemini,” Walter Burke, spacecraft chief at McDonnell Aircraft Corp., and his deputy, John Yardley, asked, “Why couldn’t we launch a Gemini as a target instead of an Agena?” McDonnell was the contractor that built the Gemini spacecraft.

NASA officials at the agency’s headquarters in Washington D.C., Cape Kennedy (now Cape Canaveral) in Florida and the Manned Spacecraft Center (now Johnson Space Center) in Texas quickly began drawing up a plan to orbit Gemini VII on its planned two-week mission and, if there was no serious damage to Launch Pad 19, send up Gemini VI to rendezvous.

At first glance, some were skeptical.

“When I first heard of this plan to rendezvous two spacecraft by launching the second spacecraft from the same pad in nine days I thought it was next to impossible,” said Andre Meyer Jr., senior assistant to the Gemini Program manager: “It normally takes nine weeks or 63 days of actual work to clean up the pad, erect the booster, mate the spacecraft and check out the systems.”

Wiley Williams, NASA’s manager of Gemini Operations at the Kennedy Space Center, explained that, while challenging, the quick turnaround was achievable.

“Barring unforeseen problems, we feel there is no reason why this schedule, tight as it is, cannot be met,” he said at the time. “Our most critical period will be after Gemini VII is gone. We are planning for only a few days ‘turnaround’ time on the pad.”

According to Charles Berry, M.D., chief of Medical Programs at the Manned Spacecraft Center, Gemini VII basically was an effort to better understand how humans adapt to microgravity.

“It’s the culmination of our efforts to double man’s exposure to the space environment with a 14-day flight,” he said. “The mission will show us that man, indeed, can adapt. That his body does not show changes that increase with his exposure to that environment. The additional data will allow us to medically commit man to a lunar mission.”

The Gemini VII crew, Frank Borman and Jim Lovell, were both from the second group of astronauts. While Lovell would go on to be command pilot of Gemini XII in late 1966, both would fly together again, with Bill Anders, as part of Apollo 8, the first astronauts to orbit the moon in December 1968. As commander of Apollo 13 in 1970, Lovell became the first person to fly four times.

“We’re on our way, Frank,” said Lovell as Gemini VII launched Dec. 4, 1965.

As the rocket exhaust began to clear, teams were standing by to begin preparing for Gemini VI.

“I was in the control center at Cape Kennedy watching the launch of Gemini VII and as the spacecraft was continuing into orbit, I glanced at another TV monitor and it showed the next launch vehicle being wheeled out of the hanger,” said NASA Gemini Program Manager Charles Matthews. “That’s how fast the action was taking place.”

The longest previous spaceflight was the eight-day mission of Gemini V. Borman noted that he and Lovell hoped to take advantage of the earlier experiences.

“One of the things we got from Gemini V was that flying in the heavier spacesuits was very debilitating,” he said. “So we were able to convince NASA that we should have a lightweight pressure suit which was developed in a very short period of time. It was very convenient because we could get out of it, and we did.”

Borman and Lovell’s work was set up to coincide with that of the prime shift team in Mission Control Houston, with both astronauts working and sleeping at the same time. The Gemini VII crew conducted 20 experiments, the most of any Gemini mission, including studies of nutrition in space.

The next attempt to launch Schirra and Stafford turned out to be one of the most harrowing in the history of America’s still young space program.

On Dec. 12, 1965, all had proceeded well right up to ignition of the twin Titan II first stage engines. Astronaut Alan Bean was serving as capsule communicator, or capcom.

“3, 2, 1, ignition … shutdown Gemini VI,” he said.

After about 1.5 seconds of firing, the engines abruptly shut down. There was no liftoff.

“My clock has started,” Schirra said.

Since the clock had started in the spacecraft, the instruments were telling Schirra liftoff had taken place. Mission rules dictated that he should immediately pull a D-shaped ring above the center console and activate the ejection seats, blasting the astronauts safely away from the fully fueled Titan II which would be falling back to the launch pad. However, Schirra’s experience from Mercury 8 paid off. He did not feel the motion of liftoff.

“I knew we hadn’t gone anywhere,” he said later. “This proves that man is better programed than any computer.”

An evaluation determined that a tail plug fell off prematurely causing the engine shutdown and the erroneous liftoff signal.

Three days later, Schirra and Stafford were finally on their way to catch up with Borman and Lovell.

The radar on Gemini VI first made contact with Gemini VII after 3 hours and 15 minutes when they were 270 miles away. Soon thereafter, Schirra established voice contact with Borman.

“We’re looking for you,” the Gemini VI command pilot said. “Hang on, we’ll be up there shortly.”

About six hours after liftoff, while passing over the Hawaii tracking station on Gemini VI’s fourth orbit, Schirra reported that he and Stafford had caught up with Borman and Lovell.

“We’re flying in formation with (Gemini) VII,” Schirra said. “Everything is go here.”

“Roger, congratulations, excellent,” said astronaut Elliott See, the capcom.

“Thank you, it was a lot of fun,” said Schirra.

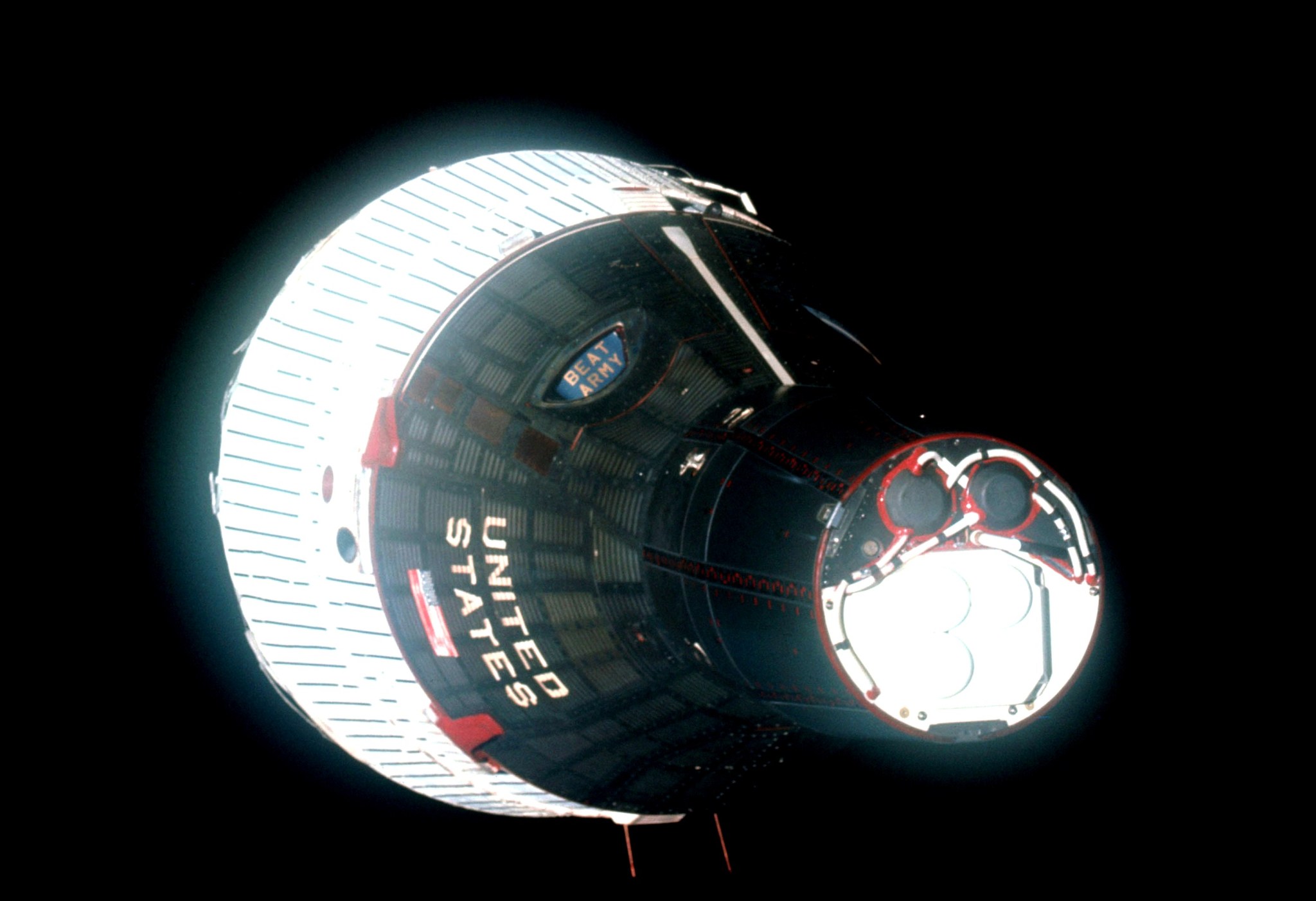

During the next five and a half hours of station keeping, the crews moved as close as one foot, taking pictures and describing the appearance of each spacecraft.

“Looks like the flag and the letters are seared as much at launch as they are when you come back at re-entry,” Lovell said, describing the side of Gemini VI.

Later, Gemini VI fired its thrusters and slowly drifted out to 10 miles, preventing an accidental collision during their sleep period.

Before the end of the day, and noting the upcoming holiday, the Gemini VI crew had a surprise for everyone.

“Gemini VII, this is Gemini VI,” Schirra said. “We have an object, looks like a satellite going from north to south, probably in a polar orbit. He’s in a very low trajectory. Looks like he might be going to re-enter soon. Stand by one …”

At that point, the sound of “Jingle Bells” was heard being played by Schirra on a small harmonica with Stafford ringing a handful of small bells.

“You’re too much, VI,” laughed See from mission control.

Gemini VI re-entered the next day, landing in the Atlantic Ocean within 10 miles of the aircraft carrier, USS Wasp.

The recovery of Schirra and Stafford also was the first to be televised. Through a transportable satellite Earth station on the deck of the Wasp, television networks were able to provide live coverage.

Gemini VII remained in space two days after Gemini VI’s return, landing Dec. 18, 1965. Borman and Lovell held the world record for the longest human spaceflight until the 17-day Soyuz 9 mission in June 1970 and were U.S. record holders until the Skylab missions in 1973 and 1974.

“The VII and VI missions were a very fitting climax to a successful year of Gemini flights,” said Matthews. “Gemini IV introduced us to spacewalking and was also the start of our buildup of long duration missions and went four days. Gemini V, in turn, went eight days. This effort on the (Gemini) 7/6 mission, is an example of the American sprit as it has existed throughout the years and is ample evidence that it exists today.”

By Bob Granath

NASA’s Kennedy Space Center, Florida

EDITOR’S NOTE: This is the fourth in a series of feature articles marking the 50th anniversary of Project Gemini. The program was designed as a steppingstone toward landing on the moon. The investment also provided technology now used in NASA’s work aboard the International Space Station and planning for the Journey to Mars. In March, read about the first docking mission and responding to an emergency in space. For more see “On the Shoulders of Titans: A History of Project Gemini.”