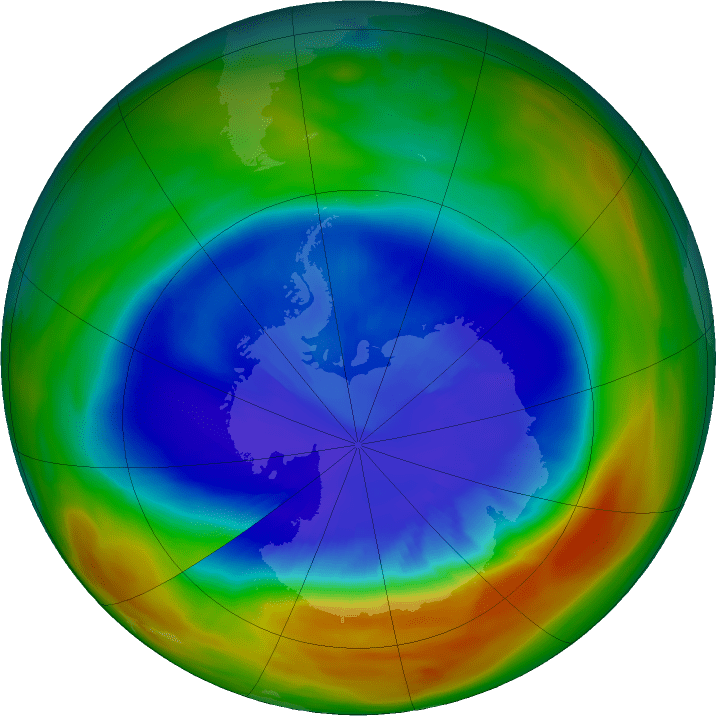

Measurements from satellites this year showed the hole in Earth’s ozone layer that forms over Antarctica each September was the smallest observed since 1988, scientists from NASA and NOAA announced today.

Credits: NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center/Kathryn Mersmann

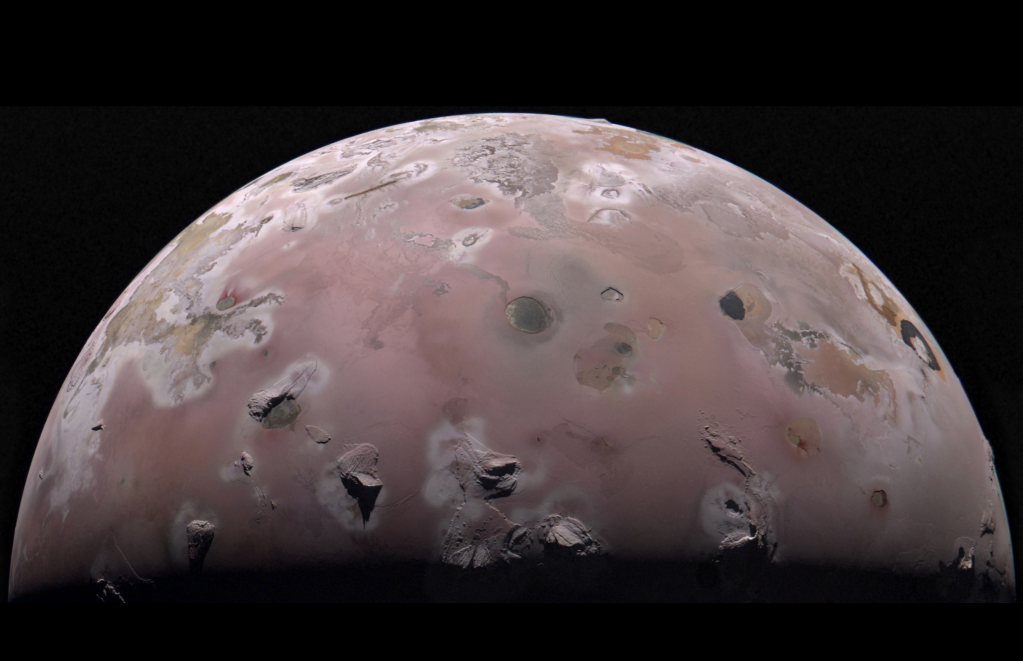

According to NASA, the ozone hole reached its peak extent on Sept. 11, covering an area about two and a half times the size of the United States – 7.6 million square miles in extent – and then declined through the remainder of September and into October. NOAA ground- and balloon-based measurements also showed the least amount of ozone depletion above the continent during the peak of the ozone depletion cycle since 1988. NOAA and NASA collaborate to monitor the growth and recovery of the ozone hole every year.

“The Antarctic ozone hole was exceptionally weak this year,” said Paul A. Newman, chief scientist for Earth Sciences at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland. “This is what we would expect to see given the weather conditions in the Antarctic stratosphere.”

The smaller ozone hole in 2017 was strongly influenced by an unstable and warmer Antarctic vortex – the stratospheric low pressure system that rotates clockwise in the atmosphere above Antarctica. This helped minimize polar stratospheric cloud formation in the lower stratosphere. The formation and persistence of these clouds are important first steps leading to the chlorine- and bromine-catalyzed reactions that destroy ozone, scientists said. These Antarctic conditions resemble those found in the Arctic, where ozone depletion is much less severe.

In 2016, warmer stratospheric temperatures also constrained the growth of the ozone hole. Last year, the ozone hole reached a maximum 8.9 million square miles, 2 million square miles less than in 2015. The average area of these daily ozone hole maximums observed since 1991 has been roughly 10 million square miles.

Although warmer-than-average stratospheric weather conditions have reduced ozone depletion during the past two years, the current ozone hole area is still large because levels of ozone-depleting substances like chlorine and bromine remain high enough to produce significant ozone loss.

Scientists said the smaller ozone hole extent in 2016 and 2017 is due to natural variability and not a signal of rapid healing.

First detected in 1985, the Antarctic ozone hole forms during the Southern Hemisphere’s late winter as the returning sun’s rays catalyze reactions involving man-made, chemically active forms of chlorine and bromine. These reactions destroy ozone molecules.

Thirty years ago, the international community signed the Montreal Protocol on Substances that Deplete the Ozone Layer and began regulating ozone-depleting compounds. The ozone hole over Antarctica is expected to gradually become less severe as chlorofluorocarbons—chlorine-containing synthetic compounds once frequently used as refrigerants – continue to decline. Scientists expect the Antarctic ozone hole to recover back to 1980 levels around 2070.

Ozone is a molecule comprised of three oxygen atoms that occurs naturally in small amounts. In the stratosphere, roughly 7 to 25 miles above Earth’s surface, the ozone layer acts like sunscreen, shielding the planet from potentially harmful ultraviolet radiation that can cause skin cancer and cataracts, suppress immune systems and also damage plants. Closer to the ground, ozone can also be created by photochemical reactions between the sun and pollution from vehicle emissions and other sources, forming harmful smog.

Although warmer-than-average stratospheric weather conditions have reduced ozone depletion during the past two years, the current ozone hole area is still large compared to the 1980s, when the depletion of the ozone layer above Antarctica was first detected. This is because levels of ozone-depleting substances like chlorine and bromine remain high enough to produce significant ozone loss.

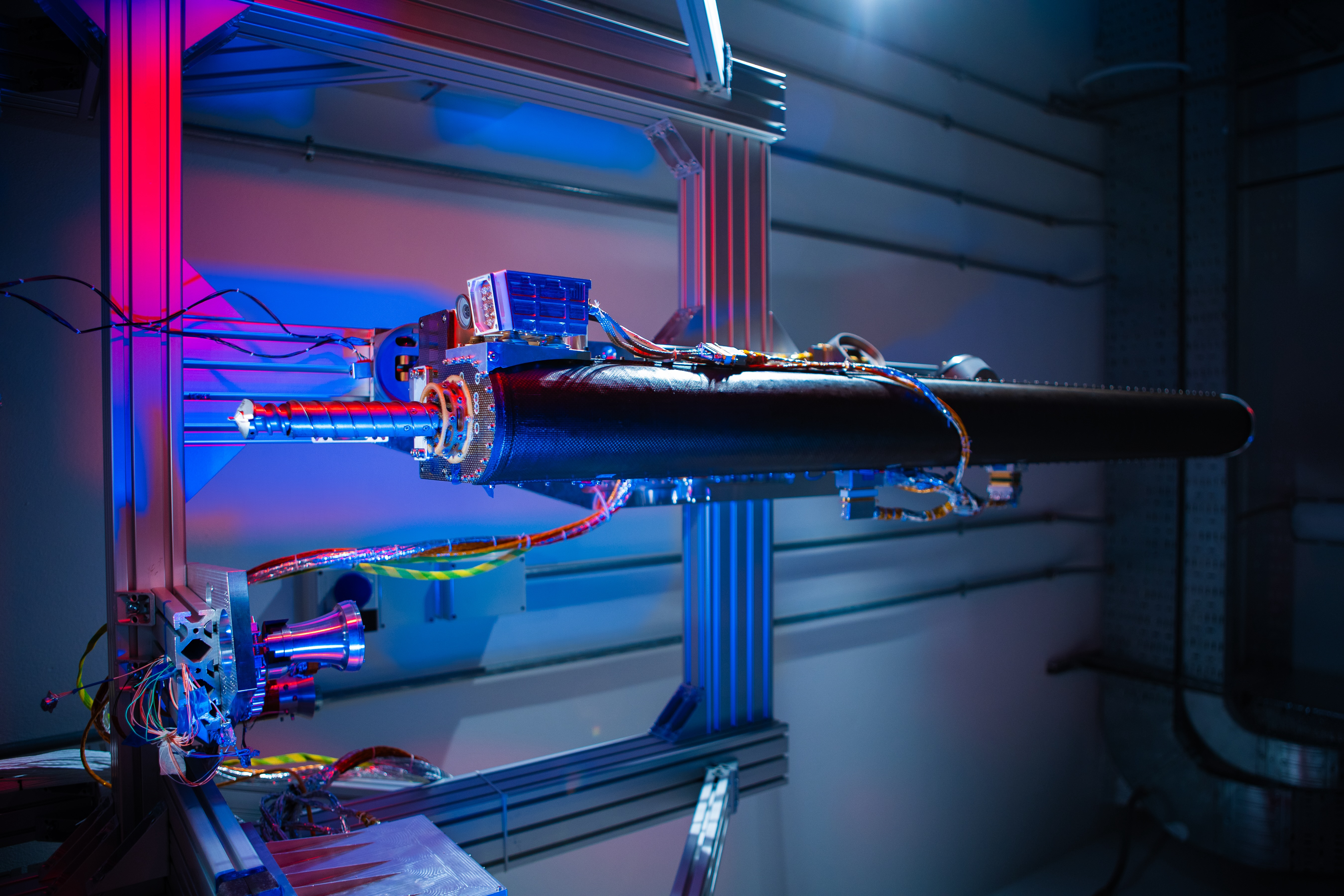

NASA and NOAA monitor the ozone hole via three complementary instrumental methods. Satellites, like NASA’s Aura satellite and NASA-NOAA Suomi National Polar-orbiting Partnership satellite measure ozone from space. The Aura satellite’s Microwave Limb Sounder also measures certain chlorine-containing gases, providing estimates of total chlorine levels.

NOAA scientists monitor the thickness of the ozone layer and its vertical distribution above the South Pole station by regularly releasing weather balloons carrying ozone-measuring “sondes” up to 21 miles in altitude, and with a ground-based instrument called a Dobson spectrophotometer.

The Dobson spectrophotometer measures the total amount of ozone in a column extending from Earth’s surface to the edge of space in Dobson Units, defined as the number of ozone molecules that would be required to create a layer of pure ozone 0.01 millimeters thick at a temperature of 32 degrees Fahrenheit at an atmospheric pressure equivalent to Earth’s surface.

This year, the ozone concentration reached a minimum over the South Pole of 136 Dobson Units on September 25— the highest minimum seen since 1988. During the 1960s, before the Antarctic ozone hole occurred, average ozone concentrations above the South Pole ranged from 250 to 350 Dobson units. Earth’s ozone layer averages 300 to 500 Dobson units, which is equivalent to about 3 millimeters, or about the same as two pennies stacked one on top of the other.

“In the past, we’ve always seen ozone at some stratospheric altitudes go to zero by the end of September,” said Bryan Johnson, NOAA atmospheric chemist. “This year our balloon measurements showed the ozone loss rate stalled by the middle of September and ozone levels never reached zero.”

Download this video at Scientific Visualization Studio.

Katy Mersmann

NASA’s Earth Science News Team

Theo Stein

NOAA Office of Oceanic and Atmospheric Research, Boulder, Co.