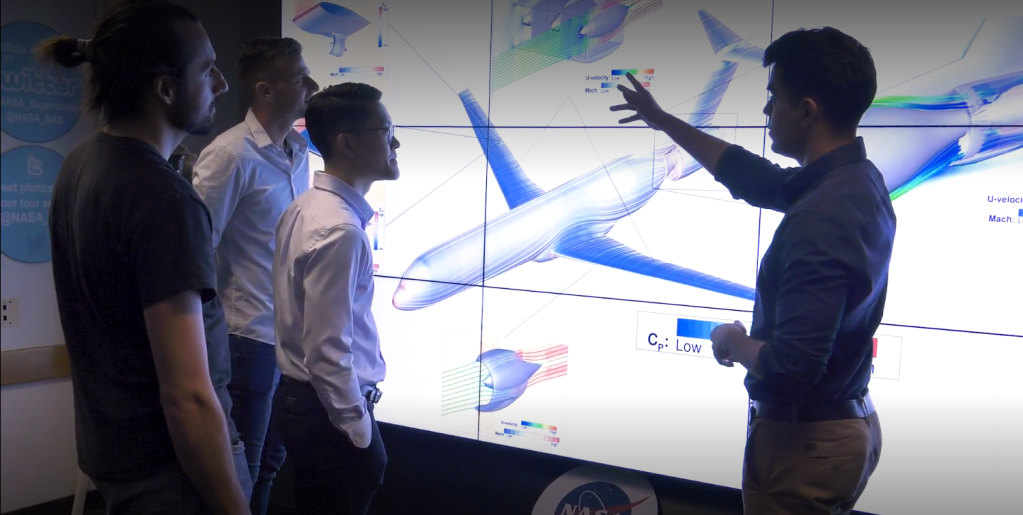

Image above: Todd May, SLS program manager, details the program’s status during a session of the National Space Club’s Florida Committee. Photo credit: NASA/Kim Shiflett

Image above: Todd May, SLS program manager, details the program’s status during a session of the National Space Club’s Florida Committee. Photo credit: NASA/Kim Shiflett

› Larger image

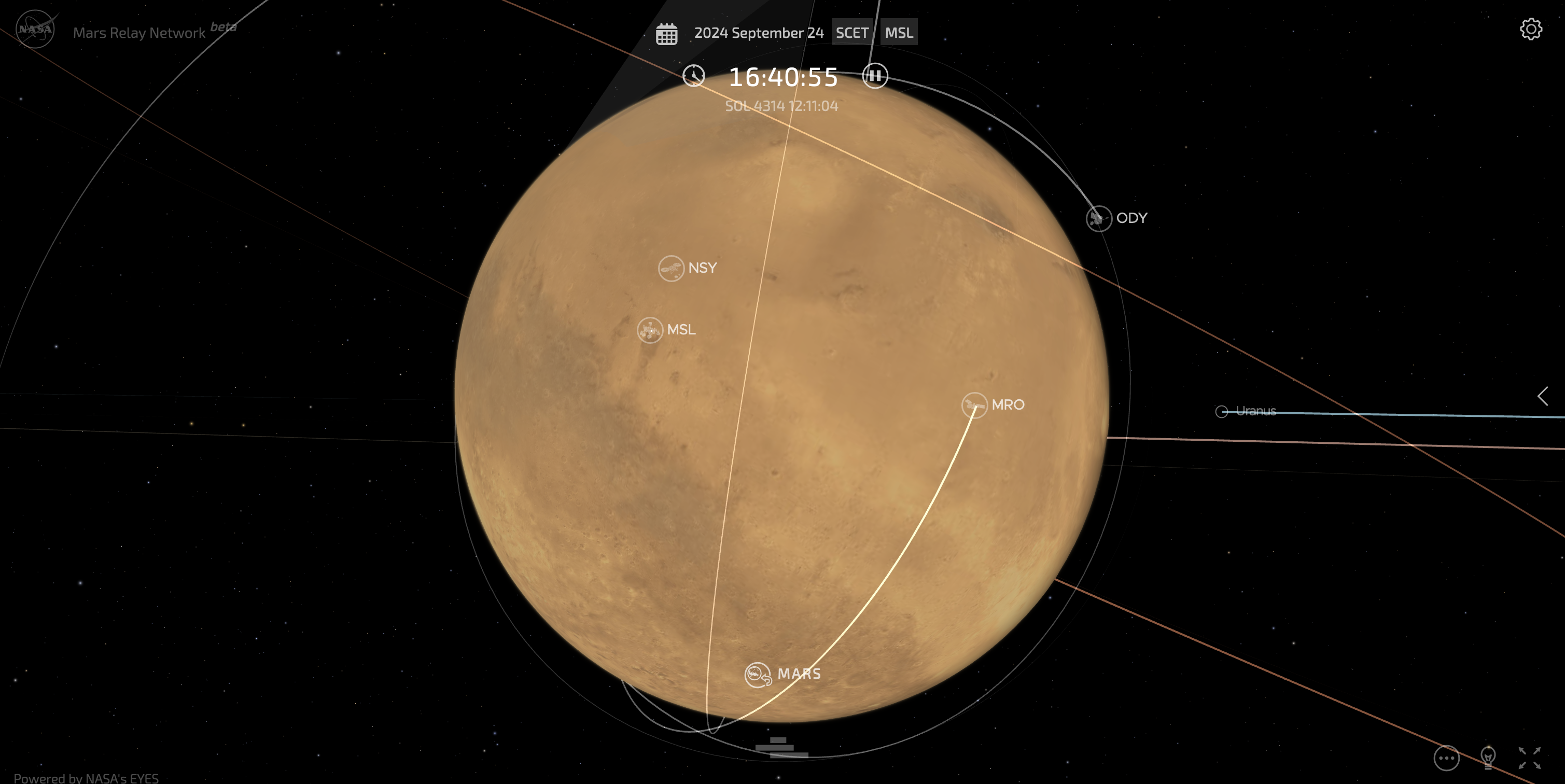

Image above: The Space Launch System stands at Launch Pad 39B in this artist concept. Concept credit: NASA

Image above: The Space Launch System stands at Launch Pad 39B in this artist concept. Concept credit: NASA

› Larger image

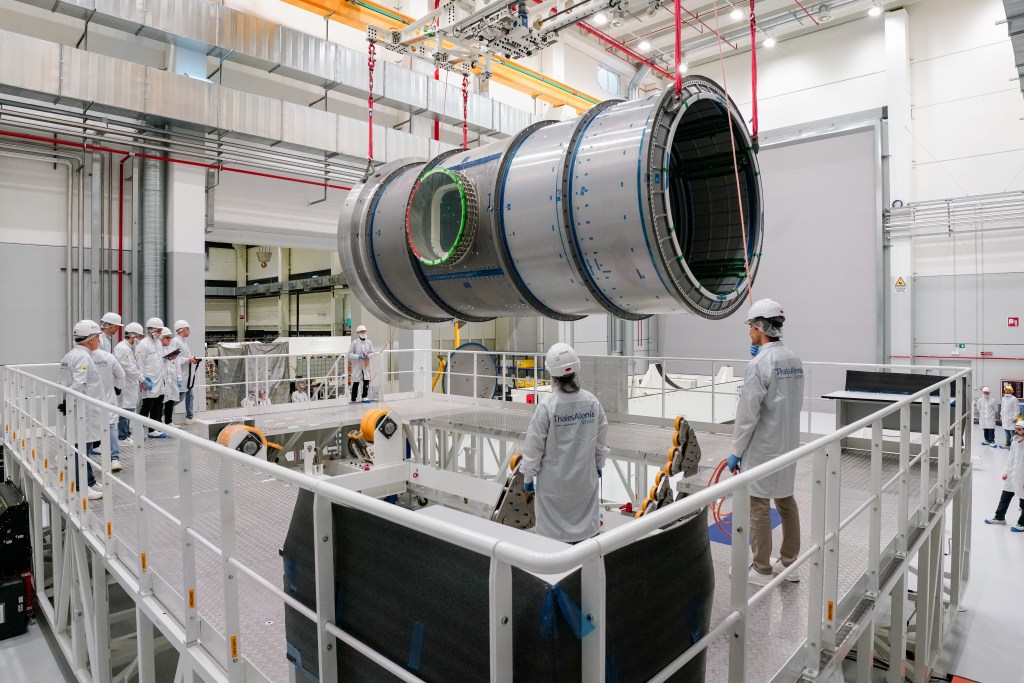

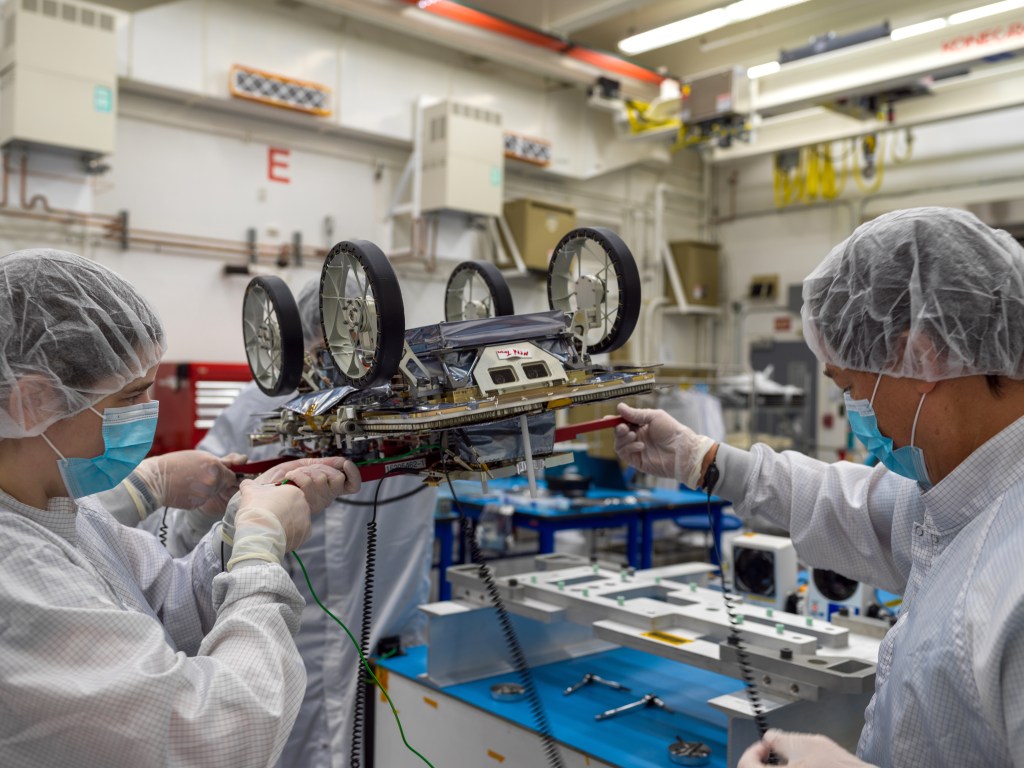

Image above: The ground test article of the Orion spacecraft is at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center for processing tests and fittings as the center prepares to outfit the Orion spacecraft that will fly the first test mission in 2014. Photo credit: NASA/Charisse Nahser

Image above: The ground test article of the Orion spacecraft is at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center for processing tests and fittings as the center prepares to outfit the Orion spacecraft that will fly the first test mission in 2014. Photo credit: NASA/Charisse Nahser

› Larger image The Space Launch System is on track to give America the launch vehicle it will need to send humans deeper into space than ever before, the program’s manager said May 8.

Speaking to the National Space Club during a luncheon near NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida, Todd May, SLS program manager, said an uncrewed test flight of the Orion spacecraft in 2014, SLS mission in 2017 and a 10- to 14-day mission with astronauts going to the moon and back in 2021 will leave the nation in a position to explore as far as it wishes.

“By that point, you’ll have the capability to go anywhere in the solar system people want to go,” May said. May leads a team of engineers and designers at NASA’s Marshall Spaceflight Center in Huntsville, Ala. “The ultimate goal is to put human boots on Mars.”

Kennedy designers also are at work to make a place for the SLS to be assembled and launched from. Launch Pad 39B has seen significant changes and the Vehicle Assembly Building is undergoing modernizations to host the 36-story-tall SLS. Also, the mobile launcher that will hold the rocket and its servicing connections already has conducted a test at the pad.

A test version of the Orion capsule is inside the Operations and Checkout Building at Kennedy and the spacecraft that will make the first test flight into space is expected in a couple of months. It will undergo final assembly at Kennedy before being mounted atop a Delta IV rocket for a mission without astronauts aboard to test the spacecraft’s systems and heat shield.

There’s a lot going on,” said Scott Colloredo, chief architect of the Ground Systems Development and Operations Program. “Whenever you see hardware moving in the direction of the launch pad, that’s always significant.”

Many elements of the SLS itself already are in testing, including the engines and solid rocket boosters that will give the rocket about 8 million pounds of thrust at launch, 10 percent more than the Saturn V.

NASA already has an inventory of space shuttle main engines that will be used to power the core stage. “The propulsion elements are in really good shape,” May said. “Sixteen space shuttle main engines, that’s a good head start.”

The SLS also will use solid rocket boosters like the shuttle, but the SLS versions will be five segments instead of four.

The core stage, which will hold the fuel tanks for the main engines, is early in its design but still is on schedule. Like the space shuttle external tanks, the core stage will be built at NASA’s Michoud Assembly Facility in Louisiana. The SLS stage is about 15 feet longer than the shuttle’s external tank, and it will be shipped to Kennedy on the Pegasus barge, another element shared with the shuttle.

The stage, complete with the space shuttle main engines on the bottom, will be shipped to NASA’s Stennis Space Center in Mississippi in early 2016 for six months of tests. Then it will come to Florida that summer where it will be stacked inside the Vehicle Assembly Building into the full rocket that will launch at the end of 2017.

May said using shuttle components where possible saved considerable design and development costs. Also, NASA is counting on savings from modern manufacturing processes and has cut the agency’s oversight requirements to further save money and time.

“We understand we’ve got to do things differently than in the past,” May said.

Managers do not expect the agency to get additional money in the future and are planning to work only with the same annual funding NASA gets now.

“Flat is the new up,” May said of the program’s budget philosophy.

The SLS is slated to be America’s biggest rocket ever, even surpassing the Saturn V that lofted astronauts and their spacecraft to the moon in the late 1960s and early ’70s. For the SLS, astronauts will fly inside an Orion capsule reminiscent of the Apollo capsules, though much larger.

To get anywhere on an SLS still requires considerable work, although the team is making steady progress. The focus now is on the version of the SLS designed to lift 70 tons into space, strong enough to send the Orion spacecraft to the moon. Later versions are expected to launch 130 tons, enough to carry landers or other spacecraft suited for whatever location astronauts head to.

“NASA hits something that speaks to the inside of all of us, the exploration,” May said. “It’s great to do things that speak to all of humankind.”

5 min read