NASA’s Orion spacecraft is not quite ready for liftoff, but the spacecraft thinks it’s already flown six missions.

Since Orion’s crew module was stacked on top of its service module in June, the vehicle has been put through a series of tests designed to verify all the individual systems work on their own in the new configuration and that they’ll work together as a functional unit during flight.

And the best way to do that is to trick the vehicle into thinking that it’s flying, so that it will perform exactly the same functions it will be called upon to perform in December, when Orion launches into space for the first time.

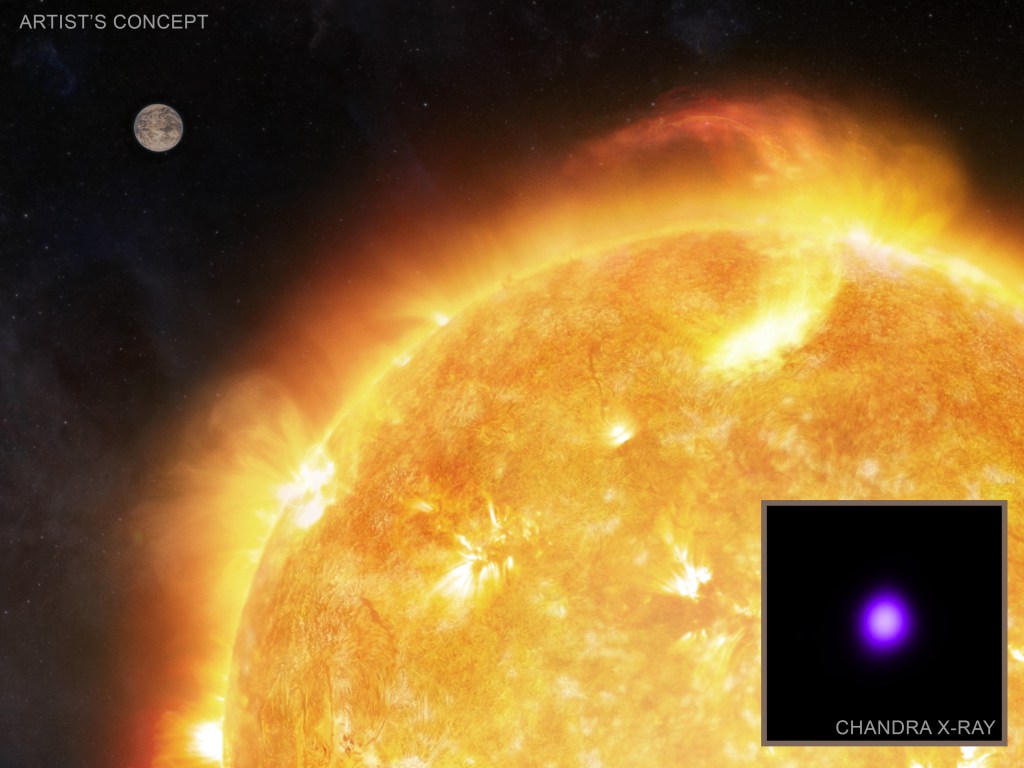

For that flight, Exploration Flight Test-1, Orion will travel 3,600 miles above the Earth – farther than any spacecraft built to carry people has traveled in more than 40 years – and return home at speeds of 20,000 miles per hour, while enduring temperatures near 4,000 degrees Fahrenheit. It will be literally a trial by fire, intended to prove that Orion can carry humans into deep space and safely return them home. But to ensure that Orion comes through it successfully, the team here on the ground wants to shake out any bugs now.

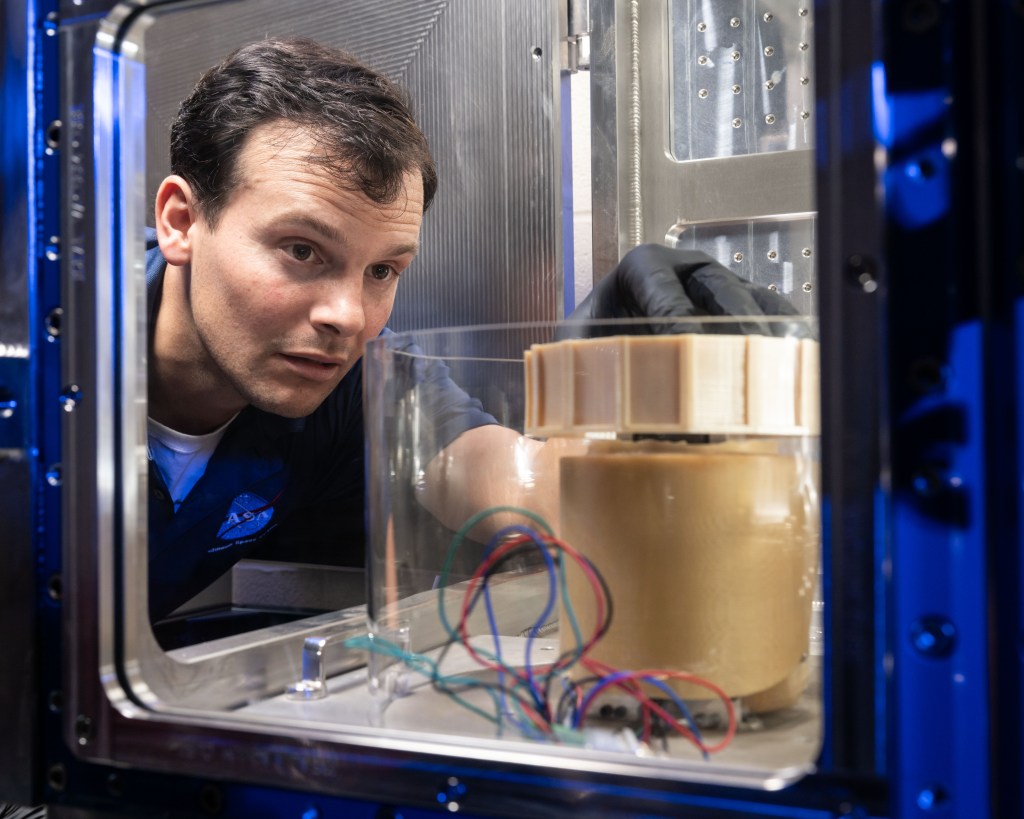

“We have ground simulation units that make the vehicle think it’s somewhere it’s not,” said Scott Wilson, manager of production operations for Orion. “We give the GPS and inertial measurement units vehicle commands and data that simulate flight. For example, we simulate the jettison of the launch abort system, and air pressure on the measurement probes. We make the vehicle think it’s experiencing all those things it sees in flight.”

In doing so, the engineers and technicians who have been building Orion at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida are able to verify that when the vehicle sees the events that it’s expected to encounter in flight, it will respond appropriately. The simulations are not a substitute for flying in space, but it’s as close as possible to get before launch.

“This is our first opportunity to see the real spacecraft perform,” Flight Director Mike Sarafin said. “You can design something on paper or in a lab, but until you put it all together and see how it works, you only have an idea of what it might look like. When you test the real system, you know what it will do.”

As the lead flight director for Exploration Flight Test-1, Sarafin has been following the tests with special interest. Along with his flight control team, which will oversee the flight from the Mission Control Center at NASA’s Johnson Space Center in Houston, he’s also used the testing as an opportunity to test his skills.

They started with the simulation of problem-free flight for Orion, and then they began adding in problems to deal with. As the first flight of a brand-new spacecraft, the flight controllers have to be prepared for things to go wrong. If Orion fails to separate automatically from the launch vehicle’s upper stage before reentry, what happens? If the high radiation Orion will see as it travels through the Van Allen Radiation Belts knocks out some of the avionics, what will Orion do, and how will the flight control team respond? To that end, they tested dozens of failure scenarios.

“These scenarios have helped us understand not only the spacecraft itself, but also the ground component,” Sarafin said. “The two have to work together, and with these tests, we’ve built a lot of confidence that we’ll be able to do that.”

In all, the vehicle and its engineers, technicians and flight control team have now gone through six simulated missions together – one without challenges and five with various simulated failures. Through them all, Sarafin and Wilson agreed, both Orion and the team performed well, which gives them the confidence to move on to the next step in Orion’s construction: the back shell.

The black thermal protection tiles that make up Orion’s back shell are some of the last elements that remain to be added before the crew module is complete. The make up the outer layer on the top section of Orion, and their installation would have blocked access to systems that might have needed repairs during the past weeks of testing. The team will now add the back shell and the forward bay cover that protects it until the end of the mission, before starting the next series of tests.