NASA is using a simple but effective technology called Laser Retroreflective Arrays (LRAs) to determine the locations of lunar landers more accurately. They will be attached to most of the landers from United States companies as part of NASA’s Commercial Lunar Payload Service (CLPS) initiative. LRAs are inexpensive, small, and lightweight, allowing future lunar orbiters or landers to locate them on the Moon.

Credit: NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center/Scientific Visualization Studio James Tralie (ADNET Systems, Inc.). Lead Producer Xiaoli Sun (NASA/GSFC): Scientist

This video can be freely shared and downloaded at https://svs.gsfc.nasa.gov/14517.

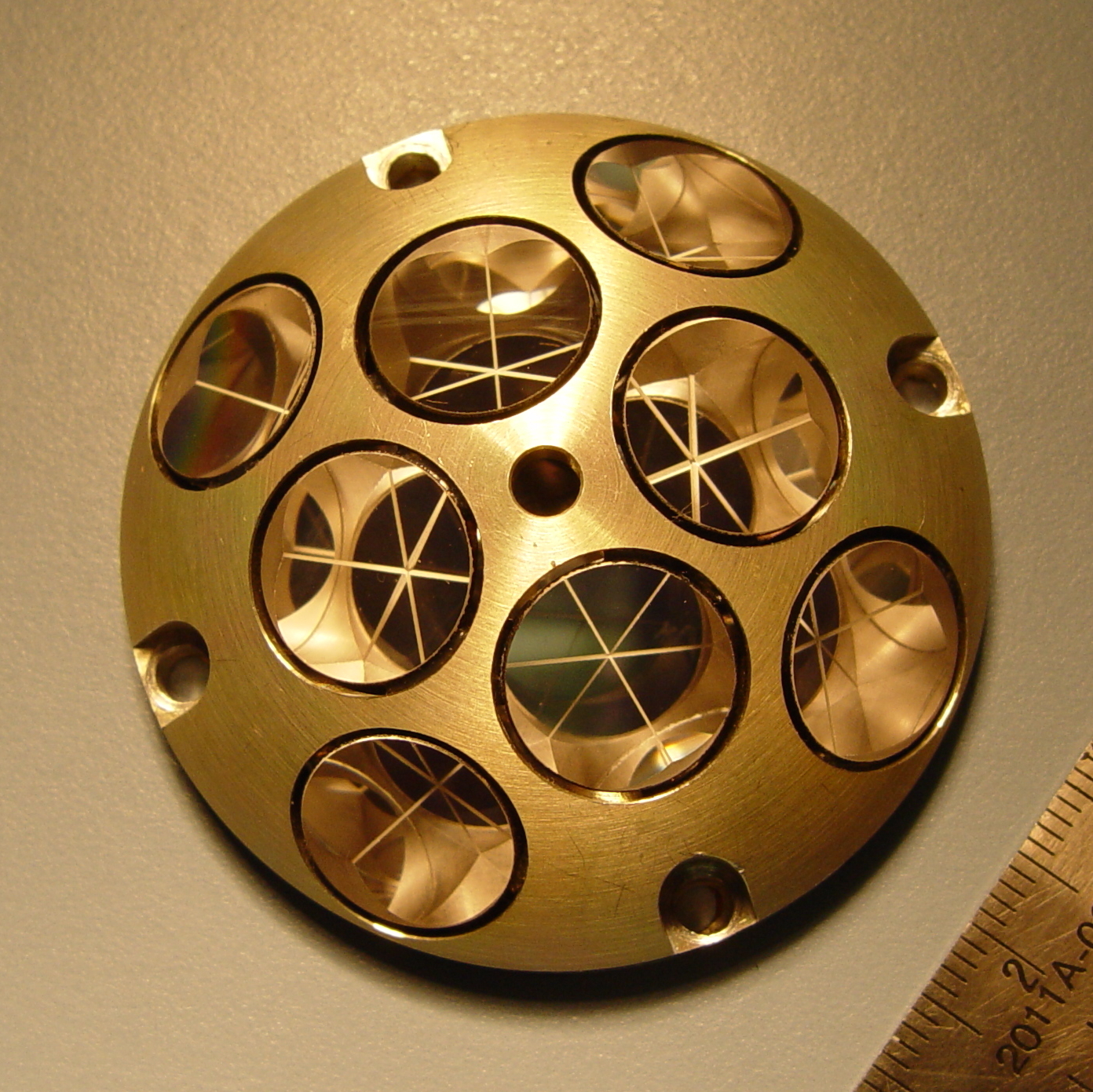

These devices consist of a small aluminum hemisphere, 2 inches (5 centimeters) in diameter and 0.7 ounces (20 grams) in weight, inset with eight 0.5-inch-diameter (1.27-centimeter) corner cube retroreflectors made of fused silica glass. LRAs are targeted for inclusion on most of the upcoming CLPS deliveries headed to the lunar surface.

LRAs are designed to reflect laser light shone on them from a large range of angles. Dr. Daniel Cremons of NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, deputy principal investigator for the LRA project, describes this as being similar to the reflective strips featured on road signs to aid in nighttime driving here on Earth. “Unlike a mirror where it has to be pointed exactly back at you, you can come in at a wide variety of angles and the light will head directly back to the source,” he said.

By shining a laser beam from one spacecraft toward the retroreflectors on another and measuring how long it takes for the light to get back to its source, scientists can determine the distance between them.

“We have been putting these on satellites and ranging to them from ground-based lasers for years,” said Dr. Xiaoli Sun, also of NASA Goddard and principal investigator for the LRA project. “Then, twenty years ago, someone got the idea to put them on the landers. Then you can range to those landers from orbit and know where they are on the surface.”

It is important to know the location of landers on the surface of another planetary body and these LRAs act as markers that work with orbiting satellites to establish a navigation aid like the global positioning system (GPS) we take for granted here on Earth.

Laser ranging is also used for docking spacecraft, like the cargo spacecraft that are used for the International Space Station, pointed out Cremons. The LRAs light up when you shine light on them which helps to guide precision docking. They can also be detected by lidars on spacecraft from far away to determine their range and approach speed down to very tight accuracy ratings, and free from the need for illumination from the Sun, which allows docking to happen at nighttime. He adds that the reflectors could allow spacecraft to accurately range-find their way to a landing pad, even without the aid of external light to guide the approach. This means that LRAs can eventually be used to help spacecraft land in otherwise pitch-dark places close to permanently shadowed regions near the lunar South Pole, which are prime target areas for crewed missions because of the resources that might exist there, such as water ice.

Since LRAs are small and made of simple materials, they can fly on scientific missions as a beneficial but low-risk add-on. “By itself, it’s completely passive,” said Cremons. “LRAs will survive the harsh lunar environment and continue to be usable on the surface for decades. Additionally, besides navigating and finding out where your landers are, you can also use laser ranging to tell where your orbiter is around the Moon.”

This means that, as more landers, rovers, and orbiters are sent to the Moon bearing one or more LRAs, our ability to accurately gauge the location of each will only improve. As such, as we deploy more LRAs to the lunar surface, this growing network will allow scientists to gauge the location of key landers and other points of interest more and more accurately, allowing for bigger, better science to be accomplished.

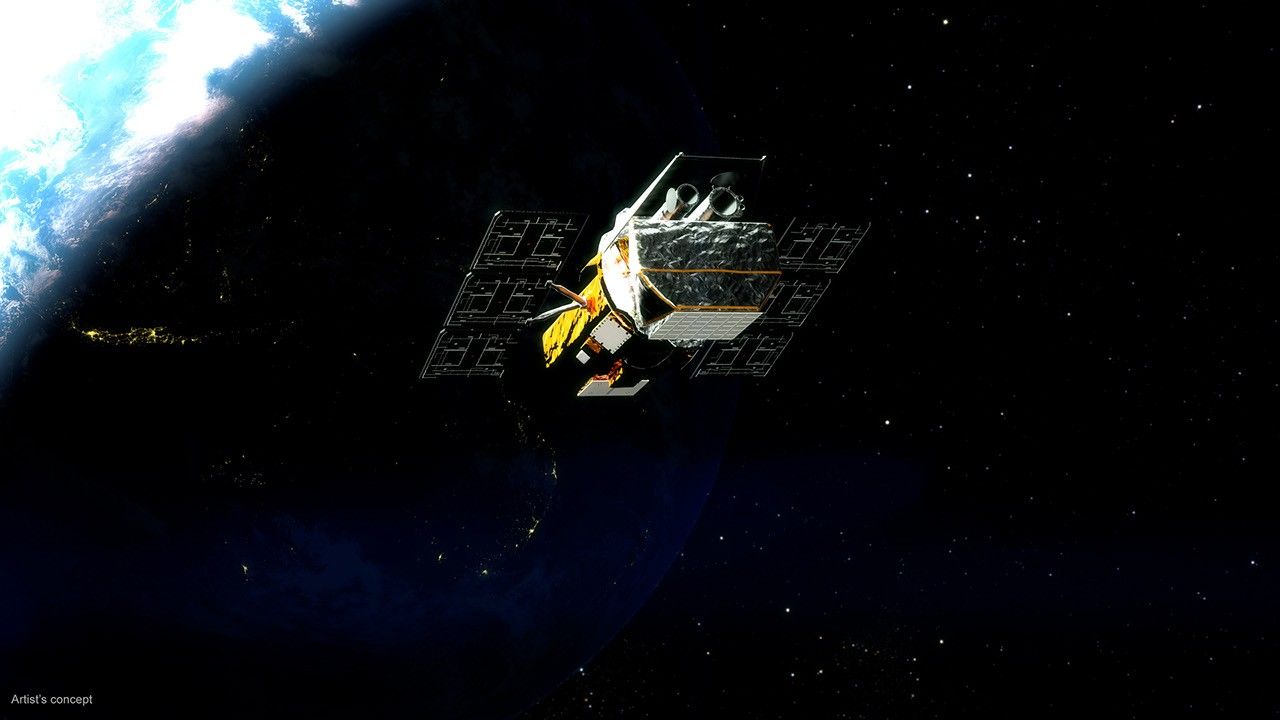

NASA’s Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO) is currently the only NASA spacecraft orbiting the Moon with laser-ranging capability. LRO has already succeeded in ranging to the LRA on the Indian Space Research Organization’s Vikram lander on the lunar surface and will continue to range to LRAs on future landers.

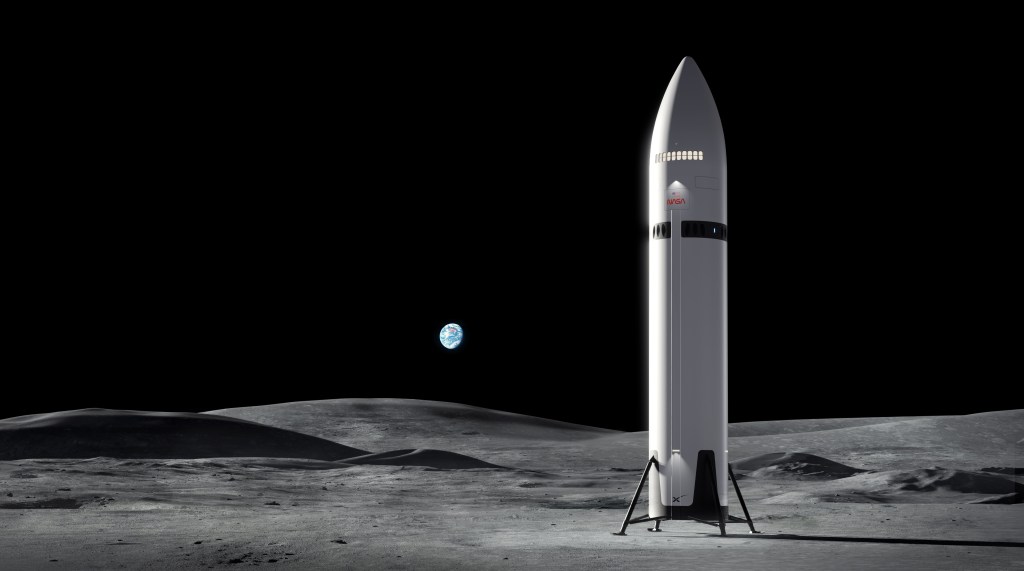

Under Artemis, CLPS deliveries will perform science experiments, test technologies, and demonstrate capabilities to help NASA explore the Moon and prepare for human missions. With Artemis missions, NASA will land the first woman and first person of color on the Moon, using innovative technologies to explore more of the lunar surface than ever before. The agency will collaborate with commercial and international partners and establish the first long-term presence on the Moon. Then, NASA will use what we learn on and around the Moon to take the next giant leap: sending the first astronauts to Mars.

By Nick Oakes

NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, Md.