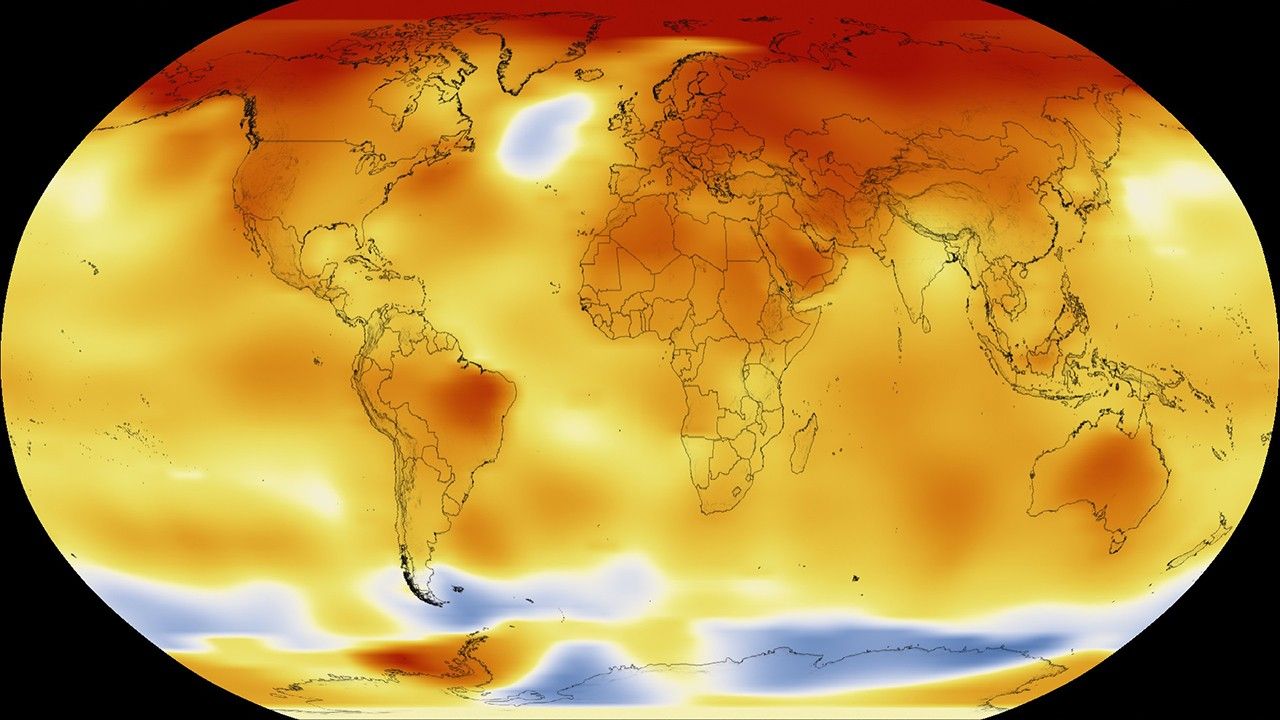

The roughly 23-million-acre National Petroleum Reserve in Alaska is rich in oil and gas resources – and rich in native fish populations. NASA scientists are combining data from water samples containing fish DNA with satellite data to find native fish and identify their habitats. This information on where native fish are located can be used to protect them and to conserve an important ecosystem in the face of human development and changing climate.

“The innovative methods in this project can determine the presence of fish species over a wide area, more efficiently than previous sampling methods,” said Jay Skiles of the Ecological Forecasting program area within NASA’s Applied Sciences Program, part of the Earth Science Division. He added that this technique of combining remotely sensed satellite data with molecular biology is a new way of measuring biodiversity.

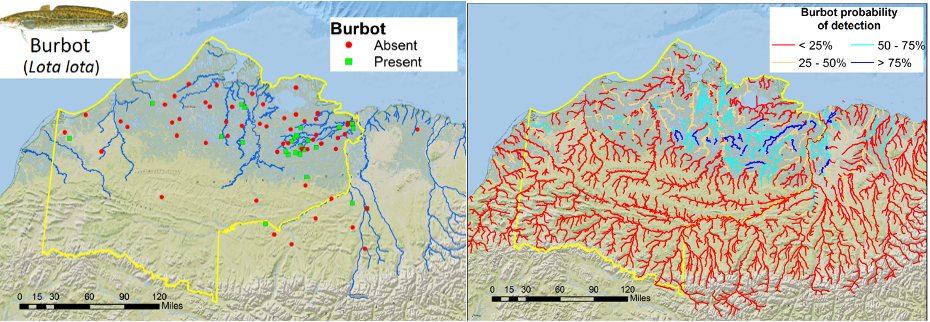

The team constructed customized maps of the predicted locations of multiple fish species for the Bureau of Land Management to use in its decision-making process. This federal agency is in charge of managing lands for multiple uses in the National Petroleum Reserve in Alaska – including oil and gas supplies, recreation, scientific research and subsistence harvests – all while conserving fish and wildlife habitats.

“For both local and landscape scale land-use proposals, the fish eDNA sampling and associated modeling will provide more widespread and comprehensive fish distribution information than what is available from scattered sampling across the vast region,” said Matthew Whitman, fish biologist for the Bureau of Land Management’s Arctic District.

Environmental DNA, or eDNA, collection involves filtering water from a river or stream and then detecting the DNA of various species in the water at the molecular level. Organisms “leak” DNA into the water through fragments of skin or waste products, which researchers can analyze and categorize to better understand the waterway’s fish populations and ecosystem.

“We realized we could help [the Bureau of Land Management] fill in data gaps at the landscape level using DNA in the water and information from NASA satellites,” said John Olson, an assistant professor at California State University, Monterey Bay and lead investigator with this project.

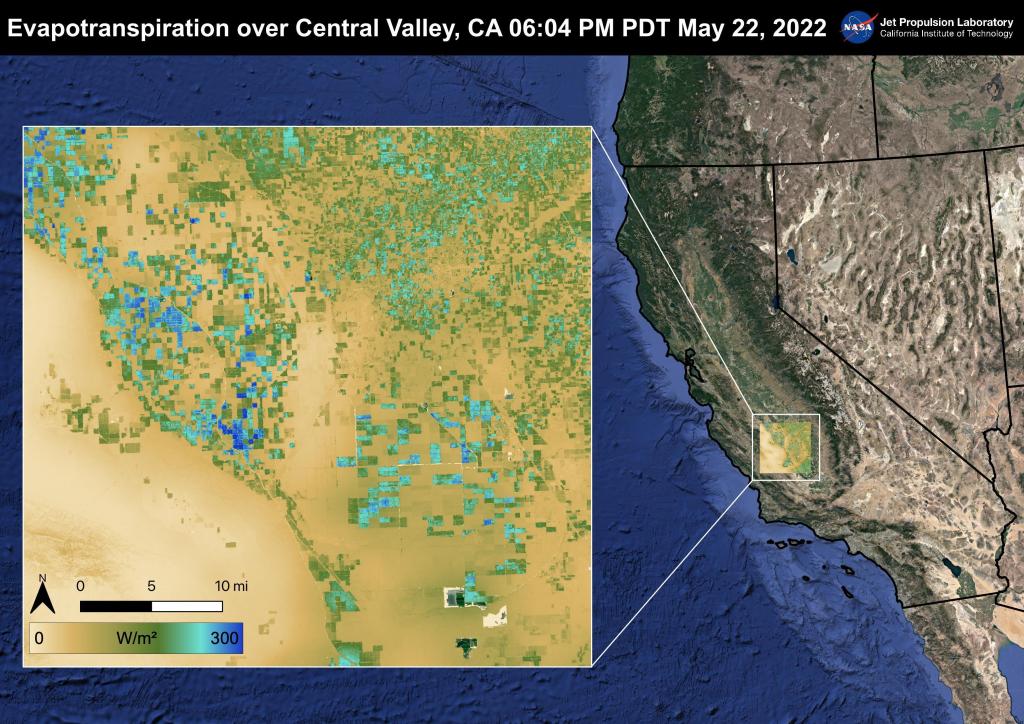

Olson’s team designed models to explore landscape characteristics, such as vegetation “greenness” and water temperatures, to create maps that estimate the probability of each species of fish appearing in a given portion of a stream.

“We were answering NASA’s call to think outside the box; to discover new ways of doing things,” Olson said. “That pushed us to come up with this idea of using environmental data in the first place.” Olson’s team combined remote sensing data from satellites with on-the-ground reports of fish populations and eDNA to predict where different species of freshwater fish might be living.

“We used remote sensing from satellites and other types of spatial data to identify a relationship – to see which fish prefer cold water or fast-moving water and which prefer waterways closer to the coast,” Olson said.

This habitat information is provided by the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) instrument aboard NASA’s Terra and Aqua satellites, along with imagery from the Landsat series of satellites, a joint mission between NASA and the U.S. Geological Survey. For example, many fish species would not live in areas where Landsat shows the landscape is dominated by dwarf shrubs, Olson explained. Those areas may be perfect for the shrubs, but too dry or with too little nutrient availability for fish to thrive. MODIS can detect land surface temperature from orbit and can tell scientists which streams are warmer. Together, the information from these two satellites allows the team to assess vegetation and other local conditions from space, which they’ve turned into a custom suite of maps.

The Bureau of Land Management plans to use the eDNA work as one more tool to inform future management decisions in the National Petroleum Reserve in Alaska and may expand its use to other parts of Alaska.

“This project developed genetic assays specifically for Arctic fish from specimens collected in the [reserve], which will be archived in a database to be available to the Bureau of Land Management, as well as other agencies, for future work,” said Whitman.

Olson adds that the project already shows such promise that his team is now working with the U.S. Department of Defense to carry out a similar project for amphibians along the coast of California.

by Lia Poteet

NASA Earth Science Division