By Mary C. White

Introduction

On May 5, 1961, the United States made its first manned space flight when Freedom 7, piloted by Astronaut Alan B. Shepard and launched from Cape Canaveral. Although this first suborbital flight lasted a mere fifteen minutes, it showed that humans were capable of surviving both the weightlessness and high G stress of space flight. With the success experienced by Freedom 7, the United States inched a bit closer to the Russian space program which already had launched a successful orbital flight on April 12, 1961 with Cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin on board the Vostok I.

A mere 20 days after Alan Shepard’s historic flight, President John F. Kennedy encouraged the U.S. to expand its role in space exploration. “Now is the time to take longer strides; time for a great new American enterprise; time for this Nation to take a clearly leading role in space achievement which in many ways may hold the key to our future on Earth.”1 President Kennedy then offered a fantastic challenge to the American people. “I believe that this nation should commit itself to achieving the goal, before the decade is out, of landing a man on the moon and returning him safely to the Earth.”2

It seemed to be an impossible task. We had limited knowledge of space when compared with the magnitude of the goal set before us. We lacked experience. We had inadequate launch vehicles. We had not even achieved orbital flight. The list of obstacles seemed endless.

However, we did have a goal. We had a vision. We had passion, dedication, grit, and determination. Slowly but surely, we moved forward. Thousands of Americans across the country combined their skills to make our space missions successful. The remaining Mercury flights proved that we could withstand the rigors of suborbital and orbital flight. The Gemini missions tackled the steps required to make a round trip to the Moon. During these flights, we proved the satisfactory operation of all major spacecraft systems and the use of controlled maneuvering. We extended the length of our flights in order to learn about the effects of long duration space flight. We refined the techniques used in extravehicular activity. We achieved rendezvous and docking capabilities. As 1967 dawned, the goal set by John F. Kennedy no longer seemed impossible. Rather, we were almost there. We still had much work to do before we actually could land an American on the Moon, but we were close. Before the last Gemini mission ended, NASA selected the three men who would fly the maiden Apollo voyage scheduled for February 1967. Commander Virgil “Gus” Grissom, Edward White, and Roger Chaffee would lead us in our quest to land a man on the Moon.

Roger Chaffee

You'll be flying along some nights with a full moon. You're up at 45,000 feet. Up there you can see it like you can't see it down here. It's just the big, bright, clear moon. You look up there and just say to yourself: I've got to get up there. I've just got to get one of those flights.

Roger Chaffee

Quoted in The New York Times, January 29, 1967, p. 48

“On my honor, I will do my best…” are the first eight words of the Scout Oath for the Boy Scouts of America. Individually, the words are short and simple. Collectively, however, they speak volumes and serve to inspire millions of boys to strive for excellence. Lieutenant Commander Roger Bruce Chaffee was a Scout for whom the Oath was more than just mere words. He took the pledge to heart and accepted the challenge to fully live the words of the Oath. Whether he was meticulously hand crafting items from wood or training to be the youngest man ever to fly in space, Chaffee always did his best by putting one hundred percent of himself into the effort.

In the early part of this century, various illnesses claimed many lives. One of the most dreaded of these diseases was scarlet fever. In January 1935, Don Chaffee came down with a case of scarlet fever and immediately was placed under quarantine. Because the disease was considered to be highly contagious and very serious, his wife, Blanche was told that she would not be allowed to deliver her baby at the local hospital; officials simply could not risk exposing other patients to the illness. Additionally, she could not give birth in their own home because of the risk of infection to both mother and newborn. Therefore, Blanche, nicknamed “Mike” and her two year old daughter, Donna moved in with her parents at their home in nearby Grand Rapids, Michigan. Roger Bruce Chaffee was born two weeks later on February 15, 1935. Toward the end of the month, Don Chaffee was removed from quarantine and brought his family back home to Greenville, Michigan, where they lived for the next seven years.

Earlier in his career, Don Chaffee had been a barnstorming pilot who flew a Waco 10 biplane. He was a regular site at fairgrounds and made a bit of extra money on the side by transporting passengers. He also piloted planes for parachute jumpers. Later, Don worked for Army Ordnance in Greenville and in 1942, he was transferred to the Doehler-Jarvis plant in Grand Rapids, Michigan where he served as Chief Inspector of Army Ordnance.

Don shared his love of flying with his son and at the age of seven, Roger enjoyed his first ride in an airplane when the family went on a short excursion over Lake Michigan. Although it was a relatively brief flight, Roger was absolutely thrilled. To satisfy his continued interested in planes, Don set up a card table in the living room where he and Roger would create model airplanes piece by piece. By the time he was nine, Roger would point to a plane flying overhead and predict, “I’ll be up there flying in one of those someday”.3

Roger’s youth was characterized by strong family ties reinforced by activities involving his mother, father and sister. Trips to the Holland Tulip Festival delighted the entire family. The Ramona Amusement Park was a wonderful summertime attraction to which the family went on a weekly basis. The Chaffees also kept in close contact with grandparents and tried to make an annual trip to Canada to visit with extended family members. Ice skating, fishing, swimming, badminton and croquet were enjoyed as a family.

Chaffee established himself as a well-rounded individual at an early age. He loved making and flying model airplanes, but he also enjoyed his electric train set which snaked throughout the living room. He inherited a love and appreciation for guns from his grandfather, with whom he would spend hours target shooting at a nearby gravel pit or cleaning and polishing their firearms. Roger became interested in music in the fifth grade, participating in the city-wide chorus and playing the French horn in the school band. He later switched to the cornet and eventually progressed to the trumpet. Once he reached high school, he put his musical talent to work by forming a band with several other boys which hired itself out to play at post-game dances.

Although his parents provided him with a small allowance as compensation for chores done around the house, Roger always had a flair for finding ways to make a little extra money. He was on the road every morning by five o’clock delivering newspapers. Some of his elderly customers greatly valued his dependability and hired him to do odd jobs and run errands. Many homeowners in the area accepted the enterprising young lad’s offer to stencil their house numbers on the front step risers for the grand sum of one dollar per job.

At the age of thirteen, Chaffee branched out his interests once again by becoming a member of a local Boy Scout troop. He soon began earning merit badges. After the first year, he had acquired a total of ten badges and was awarded the Order of the Arrow. Numerous other merit badges followed and by the time Chaffee was a high school junior, he had earned most every possible badge. Roger achieved the rank of Eagle Scout and later was presented with the Bronze and Gold Palms which signified that he had earned additional badges after becoming an Eagle Scout. Throughout his years in scouting, Roger was an enthusiastic participant at summer camp, gaining many practical skills in camping, cooking and outdoor living. He served one year as Assistant Water-Front Director teaching inexperienced scouts how to swim. His scouting experience and business sense also proved useful in his after school job at the Boy Scout section of a local department store.

By the time Roger was fourteen, he had developed an interest in electronics engineering and tinkered with various radio projects in his spare time. In high school, he received excellent grades and maintained a 92 average. Vocational tests showed that Roger’s strongest abilities were in the area of science. He also scored high mechanically and artistically. Mathematics and science were his favorite subjects, with chemistry being particularly appealing. Once the family switched to a gas heating system, Roger transformed the outdated coal bin area into his own private workshop where he spent countless hours experimenting with his chemistry set. By the time he was a junior in high school, he was leaning toward a career as a nuclear physicist. As a senior, he established a lofty goal for himself: he wanted to someday have his name written in history books. Before the world’s super powers took their first halting steps into space, Roger Chaffee had shared his dream of being the first man on the moon with his closest friends.

On June 11, 1953, Roger Chaffee graduated in the top fifth of his class from Central High School in Grand Rapids, Michigan. He applied for scholarships from Annapolis, Rhodes and the Naval Reserve Officers Training Corps (NROTC). Because he was not yet ready to make the required permanent commitment to the U.S. Navy, he felt obliged to turn down his appointment to Annapolis. The Rhodes scholarship was not available to candidates who desired to major in engineering. NROTC offered Chaffee a Naval scholarship and in September 1953, he began the fall semester at the Illinois Institute of Technology in Chicago. After living in the campus men’s hall for three weeks, he moved into the Phi Kappa Sigma fraternity house. He made the Dean’s List and completed his freshman year with a B+ average. By the end of his first year at the Institute, Chaffee had decided to combine his love of flying with his aptitude in science and mathematics in order to pursue a degree in aeronautical engineering. Having made this decision, Roger applied to Purdue University in Lafayette, Indiana which was well-known for its quality aeronautical engineering program. His request to transfer from the Illinois Institute of Technology was approved by a review board in Washington, D.C. and Purdue accepted Chaffee as a transfer student for the 1954 fall semester.

In the summer of 1954, Chaffee was scheduled to report for duty onboard the battleship Wisconsin for an eight week voyage as part of the NROTC program. In order to qualify for the duty, he was required to take extra training and complete a variety of physical tests. He performed poorly during the eye examination. One eye was so weak that he nearly was failed on the spot. However, the attending physician gave him a break and told him that he would be allowed to retake the test the next morning. Passing the eye test was critical; if Chaffee did not pass the examination, he never would fly professionally. Roger spent part of the long night walking along the shores of Lake Michigan. Before dropping off to sleep, he offered numerous prayers for successful test results. The exam was repeated the next morning. Chaffee passed with flying colors and the attending physician certified him to participate in the NROTC program aboard the Wisconsin. During the two month cruise, Chaffee docked in far-off ports in England, Scotland, France and the island of Cuba.

Chaffee found himself with some extra time on his hands between the end of his eight week naval duty and the start of the new semester at Purdue. To fill the gap, his father found him a job operating a gear cutter. The gears were molded from soft black iron and “each day he came out at the end of his shift looking like a coal miner.”4 Although he appreciated earning the extra money, Roger, who liked things neat and clean, stated, “I learned one thing on this job. I’m not going to make my living this way for the rest of my life!”5

In the fall of 1954, Chaffee arrived in Lafayette, Indiana and immediately sought out the Purdue chapter of his old fraternity. He lived at the frat house for the duration of his studies at the University. A job waiting on tables in one of the women’s residences provided him with an income, but Roger disliked working in such a prissy environment, where the character and decor definitely catered to more feminine tastes. He quickly found a different job by putting his mechanical and artistic skills to use as a draftsman for a small business near the campus. He remained with this position throughout his sophomore year. As a junior engineering student, Chaffee applied for a position in the Mathematics Department at Purdue and was hired to teach freshman math classes.

In September 1955, at the beginning of his junior year, Chaffee went on a blind date with a young woman from Oklahoma City named Martha Horn. His first impression of his date was that “she was a naive Southern girl.”6 Martha, a college freshman, considered Roger to be “a handsome but smart-alec upperclassman.”7 In spite of their first impressions of one another, they continued to date throughout the rest of the semester and by the end of the Christmas vacation, Martha had agreed to wear Roger’s fraternity pin. Chaffee introduced Martha to his parents in the fall of 1956 and confided to his father, “Dad, I’ve gone out with a lot of girls, but this is it. Someday I’ll marry Martha.”8 He followed through on his prediction and proposed to Martha Horn on October 12, 1956. The couple set a wedding date for the summer of 1957.

Chaffee’s second naval tour took place at the end of his junior year onboard the destroyer USS Perry. The points of destination for this cruise were the Scandinavian countries of Denmark and Sweden. He was unable to find temporary employment to finish out the summer break, so he began crafting a large model of a ship named The Cutty Sark to pass the time. He completed the project during spring break of his senior year. Recalling the many hours of work he had devoted to building the ship, Roger thought it was “too bad to have it sit around and gather dust.”9 He knew of a perfect spot for the ship back at Purdue. Having been elected as president of his fraternity, he had use of an office which was furnished with a large bookcase that seemed to be tailor made for housing The Cutty Sark. Therefore, he built a glass display case for his prized possession and brought it back with him to Purdue.

During his final semester at the university, Chaffee began flight training as a NROTC air cadet flying a Cessna 172. He was judged to be ready to fly solo on March 29, 1957, only 24 days after making his first flight out of the Purdue University Airport. After receiving additional dual and solo flight time, he took his private flight test on May 24, 1957 and passed with an above average grade of 86 percent. David Kress, who administered the test, recommended Chaffee for further military flight training.

On June 2, 1957, Chaffee was awarded a BS in aeronautical engineering from Purdue University. He graduated with distinction and received a key to the National Society of Engineers as a result of his solid academic performance. Although his undergraduate days were over, Roger had every intention of continuing his education. “It took me four years to learn how little I knew. Knowledge is vast. There is so much more to learn, and I am going to take advantage of every opportunity that comes along.”10

Chaffee completed his Naval training on August 22, 1957 and was commissioned as an Ensign in the U.S. Navy. Two days later, he traveled to Oklahoma City for his wedding to Martha Horn. After a 14-day honeymoon trip to Colorado, Chaffee was assigned to temporary duties in Norfolk, Virginia. In November 1957, he reported for military flight training in Pensacola, Florida where he learned to fly the T-34 and T-28. He later was transferred to Kingsville, Texas to train on the F9F Cougar jet. He advanced quickly and was scheduled to begin advanced flight instruction in November 1958. One day before he left for his aircraft carrier training, he became the proud father of a healthy baby girl, Sheryl Lyn.

Although Roger did not like the thought of leaving his wife and newborn daughter, he realized that this particular training was critical to his career advancement. Accordingly, he reported for aircraft carrier training duty on November 18, 1958. Chaffee found landing an aircraft on a carrier to be a challenge, stating that “setting that big bird down on the flight deck was like landing on a postage stamp”.11 He compared night flight to “getting shot into a bottle of ink.”12 Chaffee completed his flight training and won his wings in early 1959.

Roger was given a variety of assignments and participated in numerous training duties over the next few years. He worked extensively on the A3D photo reconnaissance plane. Because of his complete understanding of the plane, he was granted permission to fly it, thus becoming one of the youngest pilots allowed to fly an A3D. While all of the additional experience and training proved to be very good for Chaffee’s naval career, it did require him to make sacrifices at home. Although he had managed to be present for the birth of his daughter, Chaffee was in Africa on a training mission when his son Stephen was born on July 3, 1961. He was able to spend a brief period of time with his family upon his return, but was soon shipped out to California to attend Safety and Reliability School. This particular training helped him in his duties as a safety and quality control officer at the Heavy Photographic Squadron 62 at the Jacksonville, Florida Naval Air Station. One of his primary duties was to create a quality control manual geared for maintaining flight squadron operations. His guidebook was extremely precise and some considered it to be overly exacting. However, others “respected his judgment… and knew that he had their welfare at heart.”13 They were right. Chaffee already had lost more than one of his Navy buddies in flying accidents and, as a result, he became very aware that “there’s only room for one mistake. You can buy the farm only once.”14 For Roger, “there was only one way… the perfect way; nothing less would do.”15 In spite of his drive for perfection, Squadron 62 overwhelmingly supported Chaffee, in part because he never asked the men to do anything that he wasn’t willing to do himself.

Another of Chaffee’s duties while serving with the V.A.P. 62 Squadron was to photograph Cape Canaveral, which was gearing up to become the launch area for the newly created manned space program. He also flew numerous flights to Cuba, often as many as three a day. During one such mission, he took important aerial photographs which gave crucial documentation of the Cuban missile buildup. When he was not flying for the Navy, he gave private flying instructions to civilians in exchange for his personal use of their plane. Additionally, he began taking graduate level courses in engineering. Chaffee ultimately knew the direction in which he wanted to head and he knew how to get there. “Ever since the first seven Mercury astronauts were named, I’ve been keeping my studies up… At the end of each year, the Navy asks its officers what type of duty they would aspire to. Each year, I indicated I wanted to train as a test pilot for astronaut status.”16 When NASA began recruiting for its third group of astronauts in mid 1962, Roger Chaffee became part of an initial pool of 1,800 applicants who sought one of the coveted positions opening up in the astronaut corps.

In late 1962, Roger was given the opportunity to pursue a Master’s degree in reliability engineering in earnest. He gladly accepted the invitation and moved his family to Dayton, Ohio in order to study at the Air Force Institute of Technology at Wright-Patterson AFB. While keeping up with his studies, Chaffee continued to participate in astronaut candidate testing. By mid June of 1963, the number of pilots competing for the spots had dropped to 271. Various physical and psychological tests were administered repeatedly. This time, Chaffee experienced no difficulties with the eye examinations. However, one of the physical tests did show that he had a very small lung capacity. As the weeks dragged by, psychologists continued to probe their minds by administering Rorschach ink blot tests and personality inventories. They rated their intellectual capacity with standard Intelligence Quotient tests. Physicians poked, prodded, x-rayed and tested each man and managed to violate virtually every part of their bodies from head to toe in the process. No anatomical part or function was left unchecked. Chaffee stated that “They managed to thoroughly humiliate us at least three times a day!”17 After what seemed to be an eternity, the candidates completed the grueling series of qualifying exams and returned home to wait anxiously for NASA to complete its selection process.

To ease the tension of waiting for a telephone call that might never come, Roger went on a brief hunting trip to Michigan. When he returned home on October 14, Chaffee learned that NASA had called while he had been away hunting. Upon contacting the headquarters in Houston, he was told that he had been selected as one of America’s newest astronauts. On October 18, 1963, Roger Chaffee flew to Houston and was officially named to the astronaut corps. He was joined by thirteen other pilots:

- Major Edwin E. Aldrin, Jr., U.S. Air Force

- Captain William A. Anders, U.S. Air Force

- Captain Charles A. Bassett II, U.S. Air Force

- Lieutenant Alan L. Bean, U.S. Navy

- Lieutenant Eugene A. Cernan, U.S. Navy

- Captain Michael Collins, U.S. Air Force

- Mr. R. Walter Cunningham

- Captain Donn F. Eisele, U.S. Air Force

- Captain Theodore C. Freeman, U.S. Air Force

- Lieutenant Commander Richard F. Gordon, U.S. Navy

- Mr. Russell L. Schweickart

- Captain David R. Scott, U.S. Air Force

- Captain Clifton C. Williams, U.S. Marine Corps

After spending the Christmas holidays with family in Michigan and Oklahoma, the Chaffees went about the business of moving to Houston, Texas, home of the new Manned Space Center. Having been transferred so many times before, moving was second nature to them by now. They found temporary living quarters in a duplex apartment in Clear Lake City. The family remained in the apartment for several months while Roger drafted plans for their new house and finalized arrangements on a building lot in Nassau Bay. Construction of their yellow brick home began in March and was completed shortly after. The house “seemed to signal his personality – well-planned, modern, independent – white rugs and a Grecian bathtub – a lush but spick-and-span formality.”18

Although Chaffee always “wanted to fly and perform adventurous flying tasks,”19 he was realistic about his new role as an astronaut. “It won’t be just a throttle-jockey job; anyone can fly a plane, you know. It will be an engineering job, a tremendous scientific challenge.”20 However, Chaffee and the other thirteen rookies soon discovered what sixteen other men had learned already: there was much more to being an astronaut than simply knowing how to fly and work a slide rule.

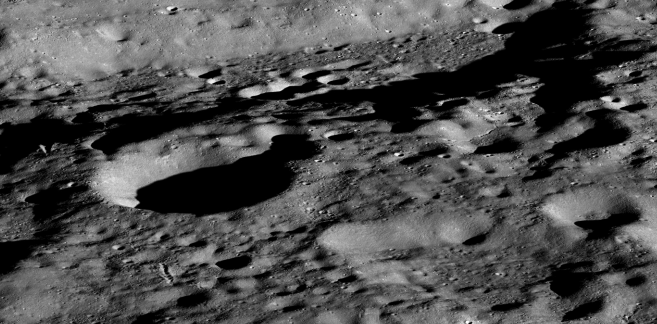

Training for the third crop of astronauts began in earnest in 1964. It was estimated that each astronaut would “spend fifty hours a week for two to five years training for a single flight”.21 The initial phase focused on academics. The instruction was intense, with various concepts and procedures from assorted professional fields crammed into countless hours of college-level lectures. Field trips supplemented the typical class work in order to gain hands-on experience. The Grand Canyon yielded information about earth’s geography. Kitt Peak National Observatory in Arizona offered opportunities to study lunar craters. New Mexico’s Slate Hill allowed the men to become familiar with the various surveying instruments and techniques which would be used to map and measure the moon. Rock formations and lava flows were studied in Alaska, Iceland and Hawaii.

Having stretched their intellects, the astronauts moved into the second phase of instruction, or contingency training. The purpose of the survival exercises was to prepare crews to handle unexpected emergencies, such as a land landing in remote areas or a crisis after splashdown. Chaffee’s introduction to the second phase of training took place in Panama where he and his colleagues were dropped into the middle of the jungle by helicopter and paired off to fend for themselves.

Thanks to his Boy Scout training, Roger had more outdoor living experience than some of the other men. Still, jungle survival was a challenge. Because the men carried only their parachutes and survival kits, they needed to make do with whatever indigenous food items they could scrounge up. Roger managed to find a variety of edibles during his three day trek. “He described the hearts of palm trees as delicious, snakes and iguana lizards as not so delicious and crabs and land snails as just plain terrible.”22

Having managed to survive for three days in a jungle environment, Chaffee and his peers moved on to dealing with a different type of contingency plan: survival in desert terrain. To achieve the maximum effect, the training took place in the desert near Reno, Nevada during the month of August when ground temperatures soared to 160 degrees. Wearing only long underwear, shoes and loose-fitting robes which they had fashioned from parachutes, the astronauts paired off for two days in the scorching desert. Lizards and snakes provided most of their meals. Inflated life rafts served as mattresses and parachutes were rigged up as tents. Once Chaffee had settled into his new “home,” he commented, “We’re real cozy… Of course, it could use some wallpaper!”23

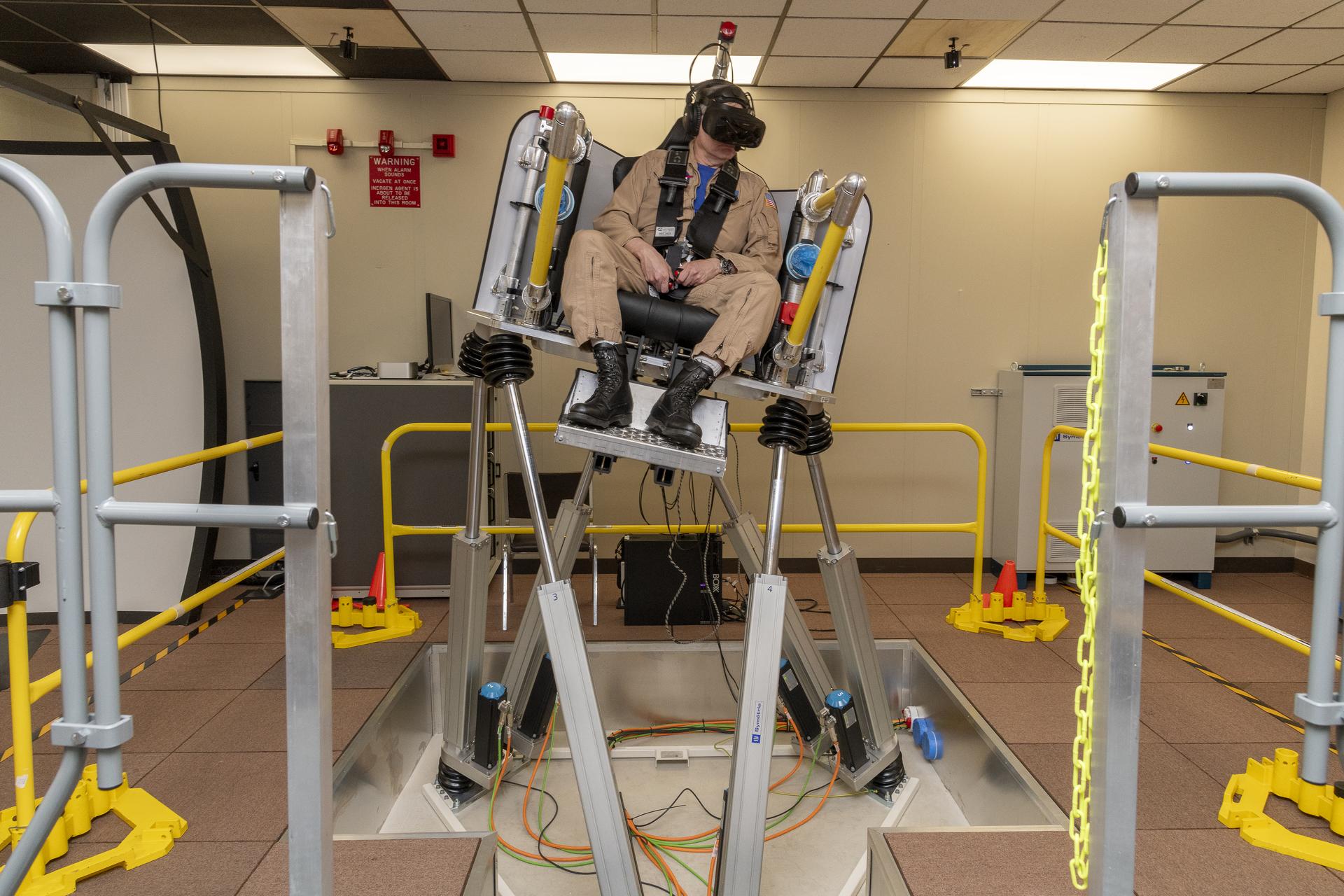

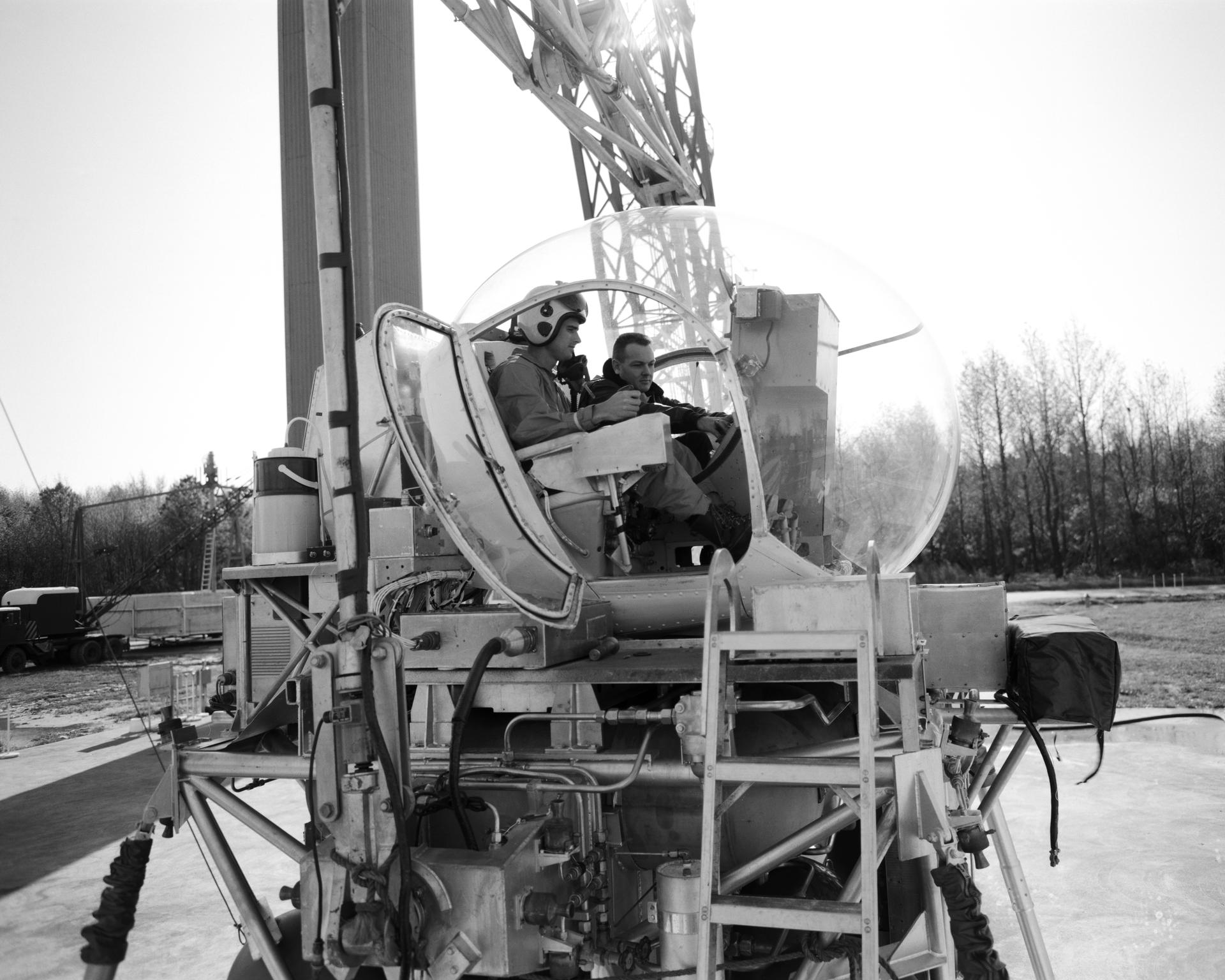

The final phase of instruction was classified as operational training and focused on exposing astronauts to the various equipment and systems associated with the spacecraft and boosters as well as the physical sensations and experiences related to space flight. Accordingly, Chaffee and his colleagues spent hours perfecting their skills in spacecraft simulators and learning how to handle problems that might occur during an actual flight. They rehearsed water egress procedures and rescue techniques. Their bodies were prepared to withstand the high G forces they would encounter during launch and reentry. Flights on board Air Force cargo planes allowed them to experience brief periods of weightlessness. Techniques and movements used in Extravehicular Activity (EVA) were refined during underwater training. They visited manufacturing plants to keep an eye on spacecraft production.

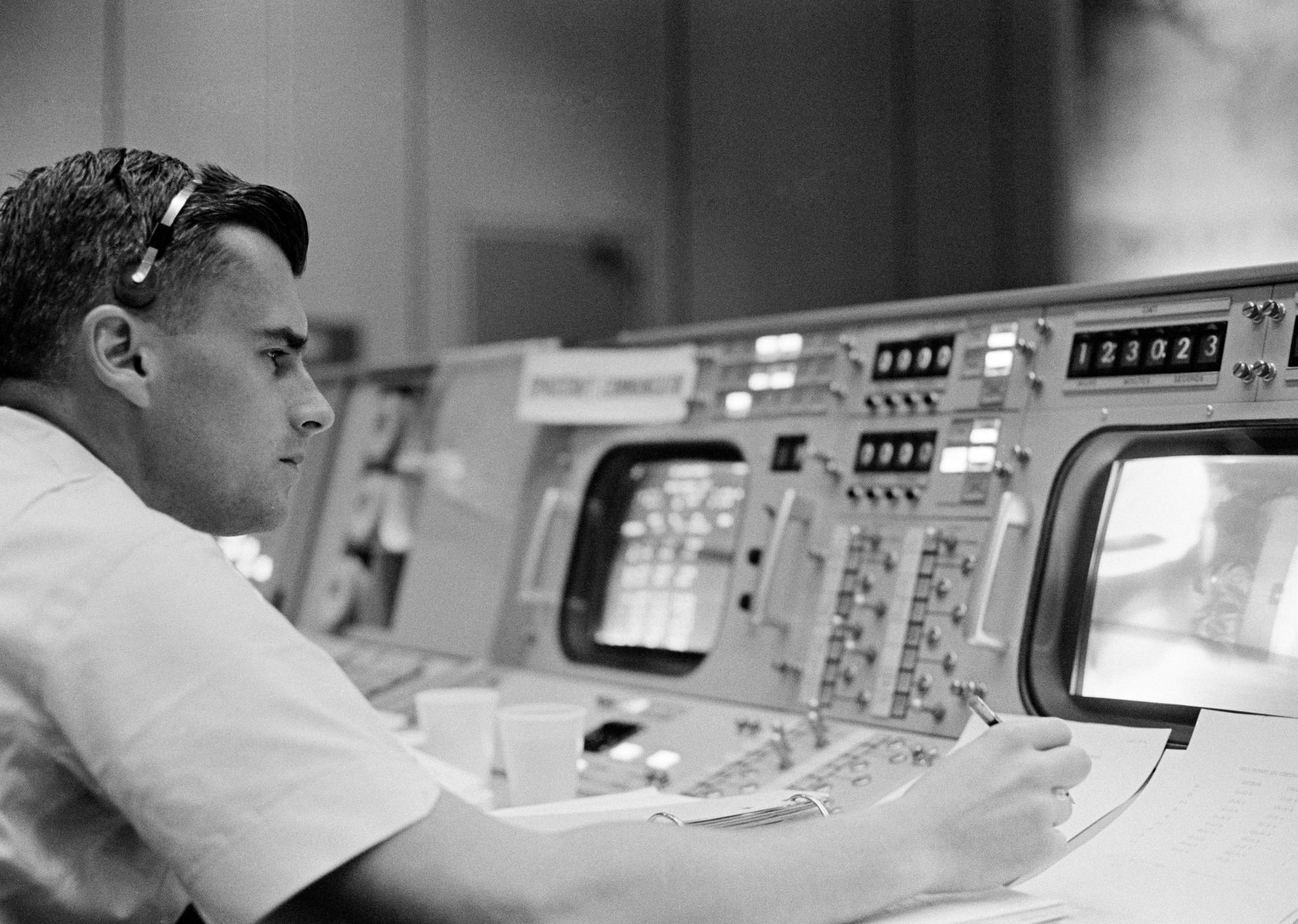

One of Chaffee’s most valuable training experiences came in the form of serving as one of the capsule communicators (capcom) for the Gemini 4 mission in June 1965. He relayed information back and forth between crew members Jim McDivitt and Ed White and the Director of Flight Crew Operations, Christopher Kraft. Chaffee served in this capacity along with Eugene Cernan and chief capcom, Gus Grissom at the recently completed Manned Space Center in Houston. He also was paired up with Grissom to fly chase planes up to a level of fifty thousand feet in order to take pictures of the launch of an unmanned Saturn 1B rocket.

On October 31, 1964, the law of averages had reared its ugly head and the astronaut corps lost its first member when Ted Freeman died in a jet crash during a routine training mission. Fate was kind for nearly two more years. Then, Charlie Bassett and Elliott See were lost when they clipped off part of the McDonnell plant building during an attempted landing in St. Louis. Although the overall death toll stood at three, no lives had been lost in accidents directly related to space flight. Chaffee served as pallbearer for Elliott See, accompanying his body as it was laid to rest in Arlington National Cemetery. Once the proper condolences had been paid, however, it was back to business as usual and the men resumed their training.

Over the years, Chaffee had developed a variety of ways to deal with all of the stress produced by the intensity and serious nature of his work. Hunting, his gun collection and home improvement projects filled his need for relaxation. He tackled each of these pastimes with the same passion he brought to his job. Roger used his woodworking skills to build a magnificent gun cabinet to house his growing collection of firearms. His first 22 rifle, which had been a gift from his parents on his twelfth birthday, a 300 Weatherby, and two old guns which Chaffee had rebuilt, reconditioned and refinished graced the cabinet. “He took great pride in making his own rifles, ordering some of the barrels and lock works from Belgium and carving the stocks from wood which he had brought back from his trip to Hawaii.”24 In addition, Chaffee never wasted his spent ammo shells. He owned all of the supplies and equipment, including scales, scoops, crimping machine, powder and ball necessary to reload his used casings.

Chaffee’s artistic streak was evident in the way he maintained his lawn and arranged the various trees, shrubs and flowers which dotted their property with the skill and eye of a professional landscaper. When Martha asked her husband to build a tiny water fountain in the backyard, she wound up with a carefully engineered waterfall crafted from tons of gravel and hours of backbreaking work. The cascading waterfall was complimented by the lighting Roger had installed around their pool. Additionally, he wired their stereo system so that music could be heard in any room of the house.

Less than one week after Neil Armstrong and David Scott completed their Gemini VIII flight, NASA named the astronauts who would fly the first Apollo Earth-orbit mission. Competition for the three positions had been intense with each man wanting a spot so badly he could taste it. Chaffee was no exception. He had been training specifically for space flight for nearly two and one half years and had yet to be named to a mission. He wanted his first flight to coincide with the first flight of the Apollo-Saturn spacecraft. When the preliminary announcement came on March 21, 1966, Chaffee discovered that he would be getting that for which he had been hoping. NASA had named Gus Grissom as Commander and Ed White as Senior Pilot. Chaffee would complete the crew as Pilot. James McDivitt, David Scott, and Russell Schweickart were assigned as members of the back-up crew. Roger enthusiastically summed up his feelings about his role as Apollo I Pilot: “I’m extremely pleased to be named. I think it will be a lot of fun.”25 Chaffee beamed with pride when Grissom made his first public statement as Apollo I Commander: “I think we have a good crew and I think it will be a good flight.”26 When “asked if there was anything scary about a first space flight, [Chaffee] replied that there were a lot of unknowns and problems. This is our business… to find out if this thing will work for us. I don’t see how you could help but be a little bit excited. I don’t like to use the word scary.”27

The primary purpose of the open-ended flight, which could last up to two weeks, was to test and evaluate all major spacecraft systems as well as the ground tracking and control facilities. The prime and back-up crews threw themselves into the intensive training schedule. Three days after the crew was first announced, Chaffee flew out to the North American Aviation Plant in Downey, California to check out production of the Apollo spacecraft. Chaffee had witnessed the manufacture and assembly of Gemini spacecraft. However, this was an entirely different situation. “We’re not talking generalities any more… That’s my spacecraft.”28 Over the next several months, Chaffee and the crew would come to know every square inch of AS 012. “We know it. We know that spacecraft as well as we know our own homes, you might say. Boy, we know every little rivet and wire and electrical terminal in it practically and all its idiosyncrasies.”29

During the months of training, the crew members worked closely together, gaining insight into individual strengths, habits and personalities in the process. Chaffee established himself as “a tireless and meticulous workhorse, the self-appointed secretary for the trip who answered the endless questions when Gus and Ed got fed up, a constant tease to them – quick with the barb, with the quiet, off-hand comeback.”30 In addition, Roger proved himself to be extremely capable and knowledgeable in his field. Gus Grissom soon recognized and came to admire his Pilot’s engineering skills: “Roger is one of the smartest boys I’ve ever run into. He’s just a damn good engineer. There’s no other way to explain it. When he starts talking to engineers about their systems, he can just tear those damn guys apart. I’ve never seen one like him. He’s really a great boy.”31 In turn, Chaffee greatly admired both Grissom and White for their own accomplishments and abilities. However, he developed a special closeness with Gus. Chaffee soon adopted a variety of mannerisms and body language that were uniquely Grissom’s. He began to pepper his speech with several of the colorful words and phrases that Gus often used. Other astronauts noticed Chaffee’s mimicry and teased him relentlessly about it. Yet, although he admired the veteran members of the crew, Chaffee never doubted his own abilities. When “asked if he felt secure under the wings of two experienced spacemen, he declared frankly: Oh, yes! But I don’t think it’s because they’ve flown and I haven’t. Hell, I’d feel secure taking it up all by myself because we’ve trained enough for every job. You feel secure because you know what you’re doing.”32

As 1966 came to a close, the crew took some time to enjoy their families during the Christmas holiday. Each year, the Nassau Bay Garden Club sponsored a Christmas contest and awarded first place to the most beautifully decorated home. Roger enthusiastically entered the contest and devoted many hours to hanging strings of colorful lights in just the right place. The piece de resistance was the roof display which featured Santa and his reindeer. To enhance the effect, Roger used a series of carefully timed flashing lights which gave the illusion of the sleigh being pulled by the reindeer. He won first place.

Christmas 1966 also gave Roger the opportunity to present his wife with a very special gift. The crew members had designed a pin for each of their wives which they had planned to take with them during the flight of Apollo I. In their excitement over the upcoming mission, they caved in and gave the pins as Christmas gifts instead. “Since they had spoiled their own surprise, immediately after Christmas they had gold charms designed that they secretly planned to take with them into space and then present to their wives. Each unique little charm was an exact duplicate of the Apollo I Command and Service Modules with a little diamond representing the astronaut’s position in the craft.”33

January 1967 found the crew involved nearly full time with the final round of pre-flight testing. In spite of his past technical and flying experience, Roger still was tagged as the rookie because he had no space flights to his credit. His solid accomplishments seemed to pale when placed next to Grissom’s and White’s. His boyish looks and young age were also obstacles. When asked to assess Chaffee as a future spaceman, Gus Grissom, who greatly valued Roger’s expertise, could only offer an educated guess regarding Chaffee’s upcoming performance: “Of course, Roger hasn’t had any experience [space] flying and we don’t know what he’ll be like. I’m sure he’ll be okay.”34 Apollo I would not be merely Chaffee’s ticket to getting his name in the history books. Apollo I would allow him, for the first time, to prove himself worthy of the title of “Astronaut” that had been bestowed upon him.

As the crew entered the Command Module for the plugs-out test on January 27, 1967, Chaffee took the Pilot’s couch on the right side of the spacecraft. His primary duty was to maintain communications with the Blockhouse as the test proceeded. The test was an extensive one that would drag on for hours so that the spacecraft could be evaluated, system by system and procedure by procedure. The job was a tough one that included numerous tedious, exacting, and frustrating tasks. Yet Chaffee’s personal philosophy and professional training had prepared him for exactly this sort ofjob.

“Probably the greatest thing a man can say to himself, or have as his philosophy when he has to tackle a tough job, or make a big decision, is the first eight words of the Scout Oath: On my honor, I will do my best…”35

As the count continued and the test proceeded, Chaffee paid close attention to the spacecraft’s performance and maintained communications with those following the test from outside the Command Module. He saw nothing on his monitors to warn him that the plugs out test soon would become a harrowing nightmare during which his own philosophy would be put to the ultimate test. Before the evening came to a close, Roger Chaffee would prove himself most worthy of the title of “Astronaut”, not by flying in space, but by choosing to remain strapped into his couch, attempting to transmit emergency messages to the Blockhouse while fire raged mercilessly throughout the Apollo I spacecraft.

Gus Grissom

If we die, we want people to accept it. We're in a risky business, and we hope that if anything happens to us it will not delay the program. The conquest of space is worth the risk of life."

Gus Grissom

Quoted in John Barbour et al. Footprints on the Moon (The Associated Press, 1969), p. 125

Lieutenant Colonel Virgil Ivan “Gus” Grissom had been part of the U.S. manned space program since it began in 1959, having been selected as one of NASA’s Original Seven Mercury Astronauts. His second space flight on Gemini III earned him the distinction of being the first man to fly in space twice. His hard work, drive, persistence and skills as a top notch test pilot and engineer had landed him the title of commander for the first Apollo flight. Yet for Grissom, Apollo I was to be just the beginning. He had been told privately that if all went well, he would be the first American to walk on the moon. Although Grissom already had stacked up a very impressive list of career accomplishments, being first on the moon would be the ultimate achievement for the man who grew up in a small town during the lean years of the Great Depression.

Virgil Ivan Grissom was born on April 3, 1926 in Mitchell, Indiana, a tiny Midwestern community of about three thousand residents tucked away in the southern half of the state. Virgil was the eldest of Dennis and Cecile Grissom’s four children, which included two brothers, Norman and Lowell and one sister, Wilma. Dennis Grissom managed to hold on to his job at the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad in spite of the numerous layoffs which were going on all around him. Although they were far from being wealthy, Mr. Grissom’s twenty-four dollar per week salary allowed his family to live comfortably in their white frame house in town.

Although Grissom was too short to participate in high school sports, he found a niche for himself in the local Boy Scout troop where he eventually served as leader of the Honor Guard. To earn spending money, he delivered newspapers twice a day throughout the year and, in the summer, he was hired by the local growers to pick peaches and cherries in the orchards outside of town.

Throughout high school, Virgil used a good portion of his money to take Betty Moore to the late shows at the local theater. He had first met her during his sophomore year and he immediately knew that she was the girl for him. “I met Betty Moore when she entered Mitchell High School as a freshman, and that was it, period, exclamation point! It was a quiet romance, as far as anyone could see, but a special closeness started then and has developed into something light years beyond the power of mere words to describe.”36

Grissom was, in his own words “not much of a whiz in school”.37 Without having set specific goals for himself, he simply seemed to drift through his classes. He excelled in math, but only pulled average grades in his other subjects. His high school principal remembered him as “an average solid citizen who studied just about enough to get a diploma.”38

However, World War II helped Grissom start forming some personal and career goals. He enlisted as an aviation cadet as a high school senior and reported for duty in August 1944 following graduation. He took a short leave during July 1945 to marry Betty Moore and returned to the base with high hopes of receiving flight instructions and flying combat missions. However, Japan surrendered a short time later and the war ended before he could receive his training. Grissom found himself going from one routine desk job to another. Knowing that he had joined the Air Force to fly and not to type, he decided to leave the service. His discharge came through in November 1945.

Grissom soon realized that his limited military career was going to get him nowhere. Eventually, he found a job at Carpenter’s Bus Body Works. However, he knew that he did not want to spend the rest of his life installing doors on school buses in Mitchell, Indiana. Therefore, he set another goal for himself. He would earn a bachelor’s degree in mechanical engineering from Purdue University.

While Gus attended classes during the day, Betty worked as a long distance operator. After class, Gus worked thirty hours a week flipping burgers at a local diner. Their combined incomes plus a small grant from the GI Bill financed the cost of his education and their “pint-sized apartment near the campus.”39 After three and one half years of study, Grissom graduated in 1950 with a BS in mechanical engineering. Many years later, Gus still was quick to give credit to Betty, for “she had made my degree possible.”40

After graduation, Gus made several half-hearted attempts to find employment. At one point, he considered accepting a mechanical engineering position at a brewery. However, because his heart was set on becoming a test pilot, he re-enlisted in the Air Force, finished air cadet training and won his wings.

Less than one year later, Grissom was shipped out to Korea to complete one hundred combat missions with the 334th Fighter-Interceptor Squadron. He ignored the tradition of naming a jet after one’s wife or girlfriend and chose to fly his F- 86 Sabre jet with the name “Scotty” boldly printed on it in honor of his son who had been born the year before. Another code of conduct existed on the bus ride which transported pilots from the barracks to the flight line. Pilots who personally had been shot at by a MIG were allowed to sit. Those who had not yet experienced a real piece of the action were unworthy of a seat and forced to stand. After only two missions, Gus took a seat on the bus. His first experience of being shot at came as a bit of a surprise. “I was flying along up there and it was kind of strange. For a moment I couldn’t figure out what those little red things were going by. Then I realized I was being shot at.”41 Grissom “usually flew wing position in combat, to protect the flanks of other pilots and keep an eye open for any MIGs that might be coming across.”42 He was proud to be able to say, “I never did get hit and neither did any of the leaders that I flew wing for.”43 After spending six months in Korea, Gus reached the one hundred combat missions mark. His request to fly twenty-five additional missions was denied and he was sent back to the states, having earned both the Air Medal with cluster and the Distinguished Flying Cross during his tour of duty.

The next few years brought a variety of assignments and changes for Grissom. He served as a flight instructor for new cadets, a task which Gus soon learned could be even more dangerous than the combat missions he had flown in Korea. “At least you know what a MIG is going to do. Some of these kids were pretty green and careless sometimes, and you had to think fast and act cool or they could kill both of you.”44

The family of three became a family of four when a second son, Mark arrived in 1953. In addition to his duties as an instructor, Grissom spent as much time as he could racking up extra flight hours and honing his flying skills. He “gained the reputation among his peers as one of the best jet jockies in the business.”45 Finally, after receiving additional instruction at the Institute of Technology at Wright-Patterson AFB, Grissom attended test pilot school at Edwards AFB. He received his test pilot credentials in 1957 and was transferred back to Wright-Patterson, where he specialized in testing new jet fighters. “This was what I wanted all along, and when I finished my studies and began the job of testing jet aircraft, well, there wasn’t a happier pilot in the Air Force.”46

Then, out of the blue, Grissom received an official teletype message instructing him to report to an address in Washington, D.C. wearing civilian clothes. The message was classified “Top Secret” and Grissom was not to discuss its contents with anyone. “Well, in the Air Force you get some weird orders, but you obey them, no matter what. On the appointed day, wearing my best civilian suit, and still as baffled as ever, I turned up at the Washington address I’d been given… I was convinced that somehow or other I had wandered right into the middle of a James Bond novel.”47 Nonetheless, as bizarre and surreal as the order might have seemed at the time, it would change Grissom’s life completely.

Grissom discovered that he was one of 110 military test pilots whose credentials had earned them an invitation to learn more about the space program in general and Project Mercury in particular. Gus liked the sound of the program but knew that competition for the final spots would be fierce. “I did not think my chances were very big when I saw some of the other men who were competing for the team. They were a good group, and I had a lot of respect for them. But I decided to give it the old school try and to take some of NASA’s tests.”48

Taking some of NASA’s tests turned out to be more of an ordeal than Grissom could have imagined. He was sent to the Lovelace Clinic and Wright-Patterson AFB to receive extensive physical examinations and to submit to a battery of psychological tests. Grissom was nearly disqualified when doctors discovered that he suffered from hay fever. Without missing a beat, Grissom informed them that his allergies would not be a problem because “there won’t be any ragweed pollen in space.”49 Since no one could argue that point, they passed him on to the next series of tests.

Grissom was pleased with his performance in all but one of the physical tests. “I was real disappointed in myself, and I thought that I should have done better” on the treadmill test.50 Like most of his colleagues, Grissom had an intense dislike and distrust of the psychological exams. It simply did not seem logical to him for grown men to be asked who they perceived themselves to be or what hidden figures or meanings they saw lurking in random blots of ink or blank sheets of paper. “I tried not to give the headshrinkers anything more than they were actually asking for. At least, I played it cool and tried not to talk myself into a hole. I did not have the slightest idea what they were trying to prove, but I tried to be honest with them…without getting carried away and elaborating too much.”51

The number of test pilots had dwindled steadily since the initial invitation to Washington had been issued. Finally, seven were chosen. On April 13, 1959, Air Force Captain Virgil Grissom received official word that he had been selected as one of the seven Project Mercury astronauts. Six others received the same notification:

- Lieutenant Malcolm Scott Carpenter, U.S. Navy

- Captain LeRoy Gordon Cooper, Jr., U.S. Air Force

- Lieutenant Colonel John Herschel Glenn, Jr., U.S. Marine Corps

- Lieutenant Commander Walter Marty Schirra, Jr., U.S. Navy

- Lieutenant Commander Alan Bartlett Shepard, Jr., U.S. Navy

- Captain Donald Kent Slayton, U.S. Air Force

“After I had made the grade, I would lie in bed once in a while at night and think of the capsule and the booster and ask myself, ‘Now what in hell do you want to get up on that thing for?’ I wondered about this especially when I thought about Betty and the two boys. But I knew the answer: We all like to be respected in our fields. I happened to be a career officer in the military and, I think, a deeply patriotic one. If my country decided that I was one of the better qualified people for this new mission, then I was proud and happy to help out.”52 Having made the decision to accept NASA’s invitation to join Project Mercury, Grissom moved his family to Langley AFB, Virginia and considered himself a very fortunate man to be participating in such a “weird, wonderful enterprise.”53

The next two years involved a constant round of crisscrossing the globe for flight training, planning and preparations, survival skills training, additional education, engineering work, monitoring spacecraft design and production and, of course, public relations. Sixteen hour days were not uncommon. After the first year, Grissom tallied up the number of days that he had spent away from home. He was surprised to discover that he had been gone for 305 of the past 365 days. Yet, the pressure was on to win the prize for being the first nation in space. Grissom and his colleagues knew that hard work and long hours were integral parts of the job. They kept their eyes on the prize and worked to get the job done.

However, the prize which awaited NASA’s team as a reward for all of their grueling work and training was snatched right out from under their noses on April 12, 1961. History would forever record that date as the day that Russian cosmonaut Yuri A. Gagarin became the first man in space when he completed his successful orbital flight aboard Vostok I. The space race had begun and we had been left behind, still stuck at the starting gate.

On May 5, 1961, Alan Shepard became the first American in space when he successfully piloted a suborbital flight on board the Freedom 7 spacecraft. His flight closed the gap a bit, but his fifteen minute suborbital flight could not compare with Gagarin’s one and three quarter hour orbital flight.

Gus Grissom had missed out on the opportunity to be the first American in space; he had been selected to fly the second flight. Shepard’s flight had been a very successful one. However, before the U.S. manned space program could move on to orbital flights, it was up to Grissom to prove that Shepard’s successful suborbital flight had not been just a fluke.

Grissom named his MR-4 spacecraft Liberty Bell 7. It seemed a logical choice “because the capsule does resemble a bell.”54 It had three significant improvements over Shepard’s spacecraft. The control panel had been redesigned to accommodate future orbital flights. A large picture window replaced the small portholes used in MR-3. This allowed the pilot to enjoy a better view but more importantly, it offered an improved capability for visual orientation of the spacecraft. Finally, Liberty Bell 7 was the first Mercury spacecraft to include a newly designed explosive hatch. Although the hatch had not been tested previously, it was considered to be superior in design to the older model used on Shepard’s capsule. The explosive hatch was held in place by seventy bolts and was opened by triggering a Mild Detonating Fuse, or MDF. By delivering a five pound blow to a special plunger, the pilot could activate the MDF which would blow the hatch completely off of the spacecraft, enabling the pilot to make a quicker and easier egress from the capsule.

After two postponements because of poor weather, Grissom’s Liberty Bell 7 finally was given the go ahead for launch on July 21, 1961. Grissom patiently waited out two holds during the countdown while strapped into his couch inside the spacecraft. The first hold was called so that a misaligned explosive bolt on the capsule’s hatch could be replaced. The second hold became necessary when cloud cover blocked the tracking cameras.

Gus reported a very smooth liftoff. The new picture window offered a panoramic view, and Grissom was mesmerized by the contrasting blackness of the sky with “the blue of the water, the white of the beaches and the brown of the land.”55 The only difficulty Grissom experienced during the actual flight was with the attitude controls, which he described as “sticky and sluggish.”56 G forces reached a peak of 11.2 during the re-entry period but were not a major problem for Grissom, who had handled up to sixteen G’s during training. The successful flight ended approximately fifteen minutes after lift-off when Liberty Bell 7 popped its chutes and landed safely in the Atlantic Ocean.

After splashdown, Grissom began final preparations for egress. “I opened up the faceplate on my helmet, disconnected the oxygen hose from the helmet, unfastened the helmet from my suit, released the chest strap, the lap belt, the shoulder harness, knee straps and medical sensors. And I rolled up the neck dam of my suit.”57 Grissom then turned his attention to preparing the hatch for egress by completing standard procedures for arming the detonator. He notified the recovery helicopter, code named “Hunt Club”, that he would need a few more minutes to mark all of the switch positions on the capsule’s instrument panel. Grissom’s final transmission was to the helicopter. “As soon as I had finished looking things over, I told Hunt Club that I was ready. According to the plan, the pilot was to inform me as soon as he had lifted me up a bit so that the capsule would not ship water when the hatch blew. Then I would remove my helmet, blow the hatch and get out.”58 Grissom was lying in his couch, waiting to receive final confirmation that it was time for him to blow the hatch and exit the spacecraft “when suddenly, the hatch blew off with a dull thud.”59 Water flooded the cabin. Grissom automatically threw off his helmet, grabbed the sill of the hatch, hauled himself out of the sinking capsule and swam furiously to get away from the spacecraft. The capsule had been equipped with a special dye marker package which would spew out its bright green contents in order to help recovery vehicles locate the spacecraft once it splashed down. The package was attached to the capsule by a set of lines. Once he was in the water, Grissom got tangled up in those lines and thus remained attached to the sinking spacecraft. He finally managed to extricate himself and swam away from the capsule. When the recovery chopper finally hooked on to the spacecraft, Grissom figured that both he and Liberty Bell 7 were home free.

The helicopter made a valiant effort to recover the spacecraft but with the added weight of the water which had flooded it, the capsule proved to be too heavy a load. Red warning lights flashed on the control panel, signifying that the extra weight was putting too much strain on the chopper and that an engine failure was imminent. The recovery team had no choice but to cut the spacecraft loose. Grissom watched helplessly as Liberty Bell sank from sight.

By now, Gus realized that he was having a hard time just keeping his head above the water. “Then it dawned on me that in the rush to get out before I sank I had not closed the air inlet port in the belly of my suit, where the oxygen tube fits into the capsule. Although this hole was not letting much water in, it was letting air seep out, and I needed that air to help me stay afloat.”60 With his suit quickly losing buoyancy, Grissom wished that he could dump the souvenirs he had stored in the left leg pocket of his space suit. “I had brought along two rolls of fifty dimes each for the children of friends, three one dollar bills, some small models of the capsule and two sets of pilot’s wings. These were all adding weight that I could have done without.”61

Unaware of the difficulty Grissom was having in staying afloat, none of the helicopters surrounding him were dropping him a life line. Their rotor blades were churning up the surface of the water, making it necessary for Grissom to swim even harder to keep from going under. He took a salty swill of the Atlantic with every wave that washed over his head. As exhaustion set in, he thought, “Well, you’ve gone through the whole flight, and now you’re going to sink right here in front of all these people.”62 Fear gave way to anger as he tried once again to wave for help, but no one seemed to respond. Finally, a third helicopter approached and dropped Grissom a horse collar. He managed to loop it over his neck and arms, albeit backwards, and was hoisted up. Grissom was so exhausted that he could not even remember that the chopper had to drag him fifteen feet across the water before he finally started going up. As soon as he was safely inside the helicopter, he grabbed the nearest life jacket and made sure that it was buckled on securely. After the ordeal he just had experienced, Grissom simply wanted to be certain that if the recovery helicopter went down and he went for another swim in the choppy waters of the Atlantic, he would be well prepared for the dunk.

Once he was on board the carrier, Grissom received a telephone call from President Kennedy. The President expressed relief that Gus was safe, but his words offered little consolation to the pilot who had flown a perfect flight but came back without his spacecraft. “It was especially hard for me, as a professional pilot. In all of my years of flying—including combat in Korea—this was the first time that my aircraft and I had not come back together. In my entire career as a pilot, Liberty Bell was the first thing I had ever lost.”63

After the flight, Grissom participated in a conventional debriefing during which he recounted the details of the flight. Grissom met his family upon returning to Patrick AFB. He was welcomed by NASA officials and held a press conference with reporters. Gus was never comfortable speaking with the press. In fact, he went to great lengths to avoid them whenever possible. On one occasion, he went so far as to disguise himself in a floppy straw hat and dark glasses in order to slip by reporters. Some members of the press crew responded by tagging him with the titles “Gloomy Gus” and “The Great Stone Face.” The press conference turned out to be an uncomfortable experience because “the reporters skipped over the successful aspects of the flight… and probed around the question of whether Grissom had contributed to the loss of the Liberty Bell by accidentally bumping the plunger which blew the hatch.”64 Grissom repeated his account. “I was just laying there minding my own business when, POW, the hatch went. And I looked up and saw nothing but blue sky and water starting to come in over the sill.”65 The second question which Grissom had to field dealt with whether or not he had felt that his life was in danger at any time. Characteristically, his response was honest and to the point. “Well, I was scared a good portion of the time. I guess this is a pretty good indication.”66 His reply made good sense. It also made good headlines and within no time, newspapers and magazines across the country shouted out variations on the same basic theme: “Astronaut Admits He Was Scared!”. The press conference finally drew to a close and James Webb presented Grissom with NASA’s Distinguished Service Medal.

Although a review board determined that Gus did not contribute in any way to the premature detonation of the hatch, questions surrounding the incident simply would not go away. “Engineers spoke of a transient malfunction but were helpless to identify it because the capsule and the hatch were now on the bottom of the ocean.”67 Grissom was frustrated by the lack of a technical explanation. “We tried for weeks afterwards to find out what had happened and how it had happened. I even crawled into capsules and tried to duplicate all of my movements, to see if I could make the whole thing happen again. It was impossible. The plunger that detonates the bolts is so far out of the way that I would have had to reach for it on purpose to hit it, and this I did not do. Even when I thrashed about with my elbows, I could not bump against it accidentally.”68

Grissom did not like the idea of being unable to come up with a concrete reason for the hatch blowing prematurely. Yet, he was not going to waste precious time worrying about it. “It remained a mystery how that hatch blew. And I am afraid it always will. It was just one of those things.”69 The important thing was that he had flown a successful flight which corroborated Alan Shepard’s experiences and the program could move ahead.

As preparations continued for the first American orbital flight, NASA announced its plan to develop an intermediate phase space program. It would feature a spacecraft that would use the Titan II as a booster and be designed to carry a two man crew. NASA officially named the program Gemini, after the constellation represented by the twin stars Castor and Pollux.

“When my Mercury flight aboard the Liberty Bell capsule was completed, I felt reasonably certain, as the program was planned, that I wouldn’t have a second space flight. By then Gemini was in the works, and I realized that if I were going to fly in space again, this was my opportunity, so I sort of drifted unobtrusively into taking more and more part in Gemini.”70

Gus liked to be in on a project from its inception and he was able to do that with Project Gemini. He combined his skills in mechanical engineering and test piloting to help produce a manned system which was designed to rely on the input of its pilots. “Gemini would not fly without a guy at the controls… It was laid out the way a pilot likes to have the thing laid out… Gus was the guy who did all that.”71

In response to NASA’s plan to build its new Manned Space Center near Houston, the Grissom family left Virginia and moved into a three bedroom home in Timber Cove, one of the new housing developments outside of Seabrook, Texas. Grissom took steps to help shield his family from the onslaught of media attention and curiosity seekers. He had a pool installed in their backyard so that they could relax and swim in privacy. Additionally, “Grissom built a house…with no windows on the side facing the street. He simply did not want people peering into his windows.”72

Grissom greatly valued being home with his family, stating that “it sure helped to spend a quiet evening with your wife and children in your own living room.”73 Betty accommodated his hectic schedule by completing major chores and errands during the week so weekends would be free for family activities. She did not wear him down by constantly grilling him about the details of his job. In turn, Gus refused to let work problems intrude on his time at home and tried to complete technical reading or paperwork after the boys were asleep. The family made what little time they had together count. They went boating and water skiing on Clear Lake. In the winter, the entire family traveled to Colorado so Gus and the boys could ski. An annual trip to the Indianapolis 500 was always a highlight and offered a chance to visit family members back in Mitchell. Gus also introduced his sons to hunting and fishing, two of his favorite hobbies. In spite of the fact that the public had thrown the Grissoms into the spotlight, Gus demanded a normal life for his family. “Betty and I run our lives as we please. We don’t care anything about fads or frills or the P.T.A. We don’t give a damn about the Joneses.”74

Once the Gemini spacecraft was completed, Alan Shepard was selected as commander for its first manned flight. Grissom was his back up. The program was progressing steadily when everything came to a screeching halt for Alan Shepard.

Shepard began to experience severe nausea, vomiting and dizzy spells. The symptoms vanished after the first episode. Shepard felt fine and saw no reason to stop working. Then the symptoms came back again… and again… and again. Shepard knew that something definitely was not right so he had the flight surgeons check him over. Much to his dismay, he wound up with a diagnosis of Meniere’s Syndrome, an inner ear disorder that caused periods of nausea, dizziness and disorientation. With symptoms like that and with no immediate cure available, it did not take long for Alan Shepard to be grounded. As a result, the commander’s seat in the first manned Gemini spacecraft would be occupied by Gus Grissom. The pilot’s seat went to Lieutenant John W. Young, a Navy test pilot with a BS in aeronautical engineering who had been part of the second group of astronauts selected in September 1962.

Grissom took his role as commander very seriously. “I was responsible for my own skin in my Mercury flight, but now that I’m going up for a second flight… I’m responsible for two. This will mean some of the decisions will come a little harder but I’ve asked for the responsibility and I’ve got it.”75

Grissom and Young, plus their backups, Wally Schirra and Tom Stafford immersed themselves in the intensive training schedule. “I had thought training for Mercury was rigorous. Once we got caught up in the Gemini training program, our Mercury training looked pretty soft.”76

Initially, Gus wanted to name his spacecraft Wapasha after a Native American tribe that had lived in Grissom’s home state of Indiana. “Then some smart joker pointed out that surer than shooting, our spacecraft would be dubbed The Wabash Cannon Ball. Well, my Dad was working for the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad, and I wasn’t too sure just how he’d take to The Wabash Cannon Ball. How would he explain that one to his pals on the B & O?”77 Wapasha got scratched off the list of prospective names and Grissom began a new search. The Broadway musical The Unsinkable Molly Brown provided him with a source of inspiration. With the loss of Liberty Bell still on his mind, Gus decided to poke fun at the whole incident. Molly Brown had been strong, reliable and most importantly, unsinkable. It was a perfect name for Liberty Bell‘s successor. However, some of Grissom’s bosses insisted that he choose a more respectable name. Gus replied, “How about the Titanic?”78 It was clear that Grissom was not going to back down on this one. Given a choice of Molly Brown or Titanic, disgruntled officials backed off. Without further ado, Gemini-Titan 3 became known as Molly Brown.

On March 23, 1965, Molly Brown successfully lifted off from Pad 19 with Grissom and Young at the controls. Gus carried with him two specially engraved watches for Scott and Mark. Betty’s souvenir, a new diamond ring, hung safe and sound on a string around Gus’ neck.

The main objectives for the five hour flight were to test all of the major operating systems and to determine if controlled maneuvering of the spacecraft was possible. Being able to change orbit and flight path was crucial to upcoming rendezvous missions, so a lot was riding on Molly’s performance. She did not let her crew down. “To our intense satisfaction we were able to carry out these maneuvers almost exactly as planned…The longer we flew, the more jubilant we felt. We had a really fine spacecraft, one we could be proud of in every respect.”79

Scientific experiments were also part of the flight plan and Grissom had to perform one of them. “It was pathetically simple. All I had to do was turn a knob, which would activate a mechanism, which would fertilize some sea urchin eggs to test the effects of weightlessness on living cells. Maybe… I had too much adrenaline pumping, but I twisted that handle so hard I broke it off.”80 Ironically, at the same time as Gus was performing his test, a ground controller was conducting an identical experiment on earth. The controller broke off his handle as well.

Another experiment that needed to be completed was testing the new array of specially packaged space food. Because future Gemini missions were scheduled to last several days, supplying the crew with an adequate diet was critical. John Young had been assigned to conduct this important experiment. Grissom constantly complained about the dehydrated delicacies concocted by NASA nutritionists. He was willing to eat the reconstituted food only because there was nothing else available. Or so he thought. Gus had no idea that John Young had more than just souvenirs stowed in his space suit pockets.

“I was concentrating on our spacecraft’s performance, when suddenly John asked me, ‘You care for a corned beef sandwich, skipper?’ If I could have fallen out of my couch, I would have. Sure enough, he was holding an honest-to-john corned beef sandwich.”81 John had managed to sneak the deli sandwich, which was one of Grissom’s favorites into his pocket. As Gus sampled the treat, tiny bits of rye bread began floating around the pristine cabin and the crew was just about knocked over by the pungent aroma of corned beef wafting through the small confines of the spacecraft. “After the flight our superiors at NASA let us know in no uncertain terms that non-man-rated corned beef sandwiches were out for future space missions. But John’s deadpan offer of this strictly non-regulation goodie remains one of the highlights of our flight for me.”82

Molly Brown splashed down at 2:15 PM after flying eighty thousand miles and completing three successful orbits around the earth. Grissom and Young were ecstatic about their textbook flight. “I do know that if NASA had asked John and me to take Molly Brown back into space the day after splashdown, we would have done it with pleasure. She flew like a queen, did our unsinkable Molly, and we were absolutely sure that her sister craft would perform as well.”83

The flight was followed by an enthusiastic reception and parade at Cape Kennedy. The following day Grissom and Young, accompanied by their families, flew to Washington. President Lyndon Johnson awarded both men NASA’s Distinguished Service Medal. “For me, personally, the finest award I received was the opportunity for my wife and two sons to meet and shake hands with the President of the United States and Mrs. Johnson and with Vice President Humphrey. It was, I know, a moment that Scott and Mark Grissom will remember for the rest of their lives.”84 Ticker-tape parades in New York and other cities followed. “After all the Russian space spectaculars, the United States was back in the manned space flight business with probably the most sophisticated spacecraft in the world, or out of it. Our reception was the public’s way of expressing pride in a national achievement.”85

Molly Brown‘s flight was followed by nine other manned missions. Each flight gave the program a wealth of knowledge, techniques and much-needed confidence. With each successful mission, we advanced closer to the moon.

Grissom remained directly involved with the Gemini program for quite some time, including several months of training as backup commander for the Gemini 6 mission. At the same time, work on the Apollo spacecraft was already well in progress. In March 1966, NASA publicly announced that Gus Grissom had been assigned as commander for the first Apollo Earth-orbit mission. Ed White would serve as Senior Pilot and Roger Chaffee was named Pilot. Jim McDivitt, David Scott and Russell Schweickart were assigned as backups. By the time Gus was freed up from his duties on Project Gemini to jump on board the Apollo program, the spacecraft and its systems were well advanced in terms of production and testing. Unlike Gemini, Grissom and his crew inherited a spacecraft that had been designed for them, but not with them.

Although they did not have a hand in the basic design process, Grissom and his crew were able to exert some influence on Spacecraft 012 which was scheduled for an October 1966 launch. “He and Ed White and Roger Chaffee, along with their supporting staff of engineers and technicians, participated directly in the progressive design and manufacturing reviews and inspections as Spacecraft 012 neared completion. Some of the things Gus saw he did not like.”86

As the pressure mounted and dissatisfaction grew, Grissom, for the first time, began to bring his work problems home. “When he was home he normally did not want to be with the space program. He would rather be just messing around with the kids. But now he was uptight about it.”87

The arrival of Spacecraft 012 to the Cape only brought more problems. It soon became obvious that many designated engineering changes were incomplete. The environmental control unit leaked like a sieve and needed to be removed from the module. As a result, the launch schedule was delayed by several weeks. The Apollo simulator which was used for training purposes had its own set of problems and was not in any better shape than the actual spacecraft itself. According to Astronaut Walter Cunningham, “We knew that the spacecraft was, you know, in poor shape relative to what it ought to be. We felt like we could fly it, but let’s face it, it just wasn’t as good as it should have been for the job of flying the first manned Apollo mission.”88 Nonetheless, the crew made do with what they had and by mid January of 1967, preparations were being made for the final preflight tests of Spacecraft 012.

On January 22, 1967, Grissom made a brief stop at home before returning to the Cape. A citrus tree grew in their backyard with lemons on it as big as grapefruits. Gus yanked the largest lemon he could find off of the tree. Betty had no idea what he was up to and asked what he planned to do with the lemon. ” ‘I’m going to hang it on that spacecraft,’ Gus said grimly and kissed her goodbye.”89 Betty knew that Gus would be unable to return home before the crew conducted the plugs out test on January 27, 1967. What she did not know was that January 22 would be “the last time he was here at the house.”90

Ed White

I think you have to understand the feeling that a pilot has, that a test pilot has, that I look forward a great deal to making the first flight. There's a great deal of pride involved in making a first flight.

Ed White

Quoted in The New York Times, Jan 29, 1967, p. 48

There is no typical path which leads a person to become an astronaut. For some, aerial combat or test piloting in one of the armed forces leads to a career in space flight. Some develop a curiosity and love of flying during adolescence. Others recall a childhood filled with memories of making airplanes from paper or balsa wood and flying with nothing more than a cardboard box for a cockpit and imagination for fuel. Others, however, were “actually born into flying.”91 Edward White fell into this category. For Ed White, flying was not merely a hobby, fascination or job. Flying was his birthright.

Edward Higgins White, II was born on November 14, 1930 in San Antonio, Texas. His father was a West Point graduate who served in the United States Air Force. He became known as a pioneer in aeronautics, beginning his military career by flying U.S. Army balloons. As the years went by and more emphasis was placed on powered flight, he switched to flying powered aircraft. By the time he retired from the Air Force, White’s father had earned the rank of major general.

White’s parents instilled a variety of personal qualities in their son. They taught him the value of self discipline, persistence and single minded dedication. They also modeled to him the importance of seasoning such a highly focused life with a good dose of laughter and fun. White learned his lessons well and successfully used these qualities throughout his personal and professional life.

At the age of twelve, when most other boys were flying model airplanes, Ed went up in an old T-6 trainer with his father. It was an experience he would long remember. Even though “he was barely old enough to strap on a parachute”92 his father allowed him to take over the controls of the plane. Ed recalled that “it felt like the most natural thing in the world to do.”93 Rather than experiencing a crippling sense of fear, the twelve year old boy displayed a sense of calm confidence which was the product of the main lesson his parents had taught him: Set a goal, believe in your heart and soul that you can achieve it and then work to accomplish it.

Because Ed’s father was a career military officer, the family moved numerous times to various Air Force bases around the country. As a result, Ed learned to adjust to new situations, people and places. Ed was considered to be a very good student and an excellent athlete in whatever school he attended. In fact, the constant shuffling from one Air Force post to another did not create any major difficulties for White until he was enrolled in Western High School in Washington, D.C. Once he began researching the admission policies at his college of choice, the lack of a continuous residency presented an obstacle.

The White family had a long and proud history of service in the various branches of the military. In addition to his father’s career in the Air Force, two of Ed’s uncles had solid careers in the Army and Marines. West Point had graduated two members of the White family “and there never seemed to be any question that I would go there too. But most military families don’t have a permanent residence so we didn’t have a congressman to appoint me to the Academy.”94

White knew that he would need to be sponsored as an at-large appointee if he was going to follow in his father’s and uncle’s footsteps and attend West Point. In order to obtain the coveted appointment, Ed would “go up and down the halls of Congress knocking on doors… [and] finally knocked on enough doors to get an appointment.”95 Following his high school graduation, the United States Military Academy at West Point opened its doors to Edward H. White, II, the newest member of the White clan to walk down its hallowed halls.