Cool flames, flames that burn at extremely low temperatures, are nearly impossible to create in Earth’s gravity. However, they are easily produced in the microgravity environment of the International Space Station.

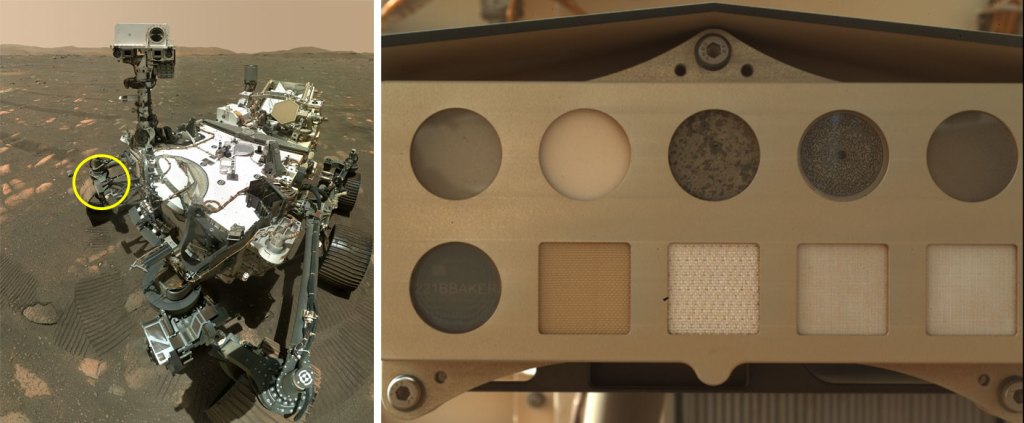

Non-premixed cool flames, created when fuel and oxidizer are not mixed before reacting, were discovered in 2012 aboard the space station during the Flame Extinguishment (FLEX) studies, helping spawn a rapidly growing research field into the nature of cool flames.

“There have been significant advances in cool flame research and understanding since 2012. The discovery of steady non-premixed cool flames has allowed a more detailed study of cool flames and their chemistry,” says NASA’s Glenn Research Center Scientist Daniel Dietrich.

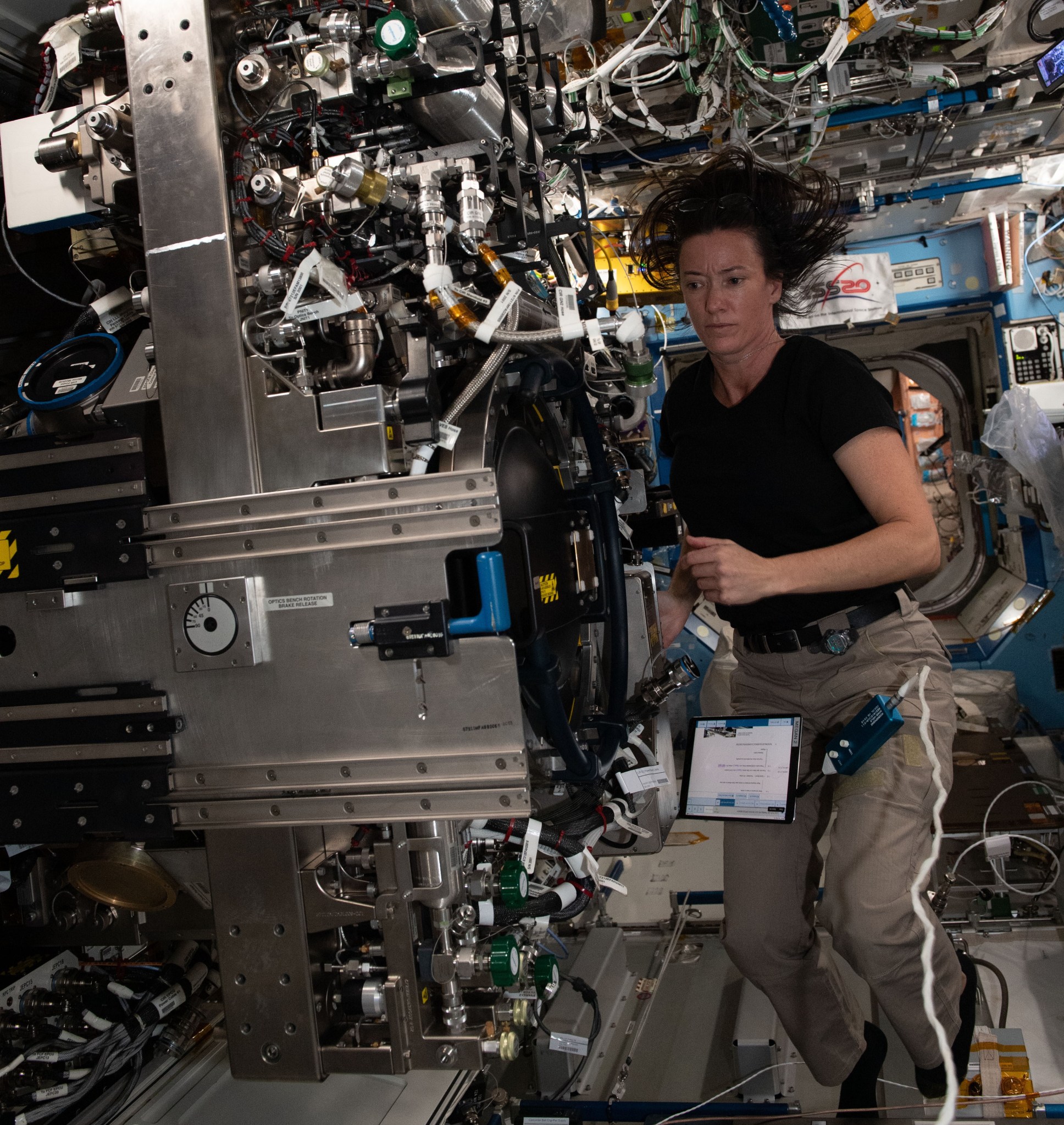

New research conducted aboard the orbiting laboratory in June 2021 has now achieved another first for microgravity flame research.

Data from tests conducted for the Cool Flames Investigation with Gases (CFI-G), sponsored by the ISS U.S. National Lab and National Science Foundation, show the presence of cool flames. While the flames created aboard station in 2012 burned liquid fuel, these new cool flames burned gaseous fuels. This was the first time spherical non-premixed cool flames have been observed burning gaseous fuels.

The results of this investigation could lead to cleaner, more efficient internal combustion engines.

“Cool flames are important to study because engine technology is trending toward lower temperatures. Little is known about combustion chemistry at these temperatures, and experiments like CFI-G could help,” says CFI-G Principal Investigator Peter Sunderland.

While cool flames are important in engines, most internal combustion engines are designed using computer models that ignore their chemistry. Cool flame chemistry also has a significant impact on fuel octane and cetane ratings, numbers that describe the performance and ignition of fuel. Understanding these can have major economic consequences.

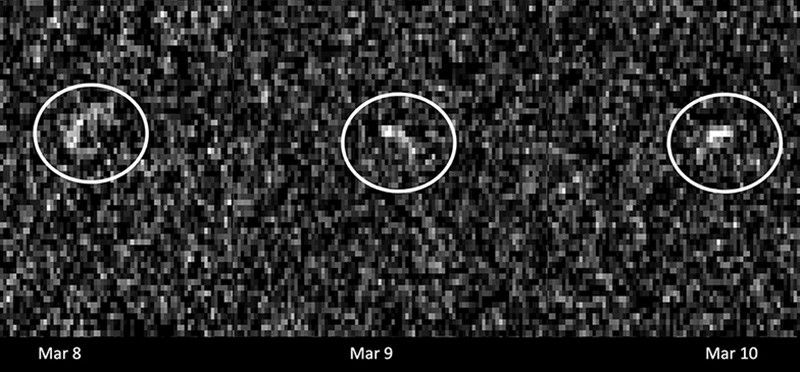

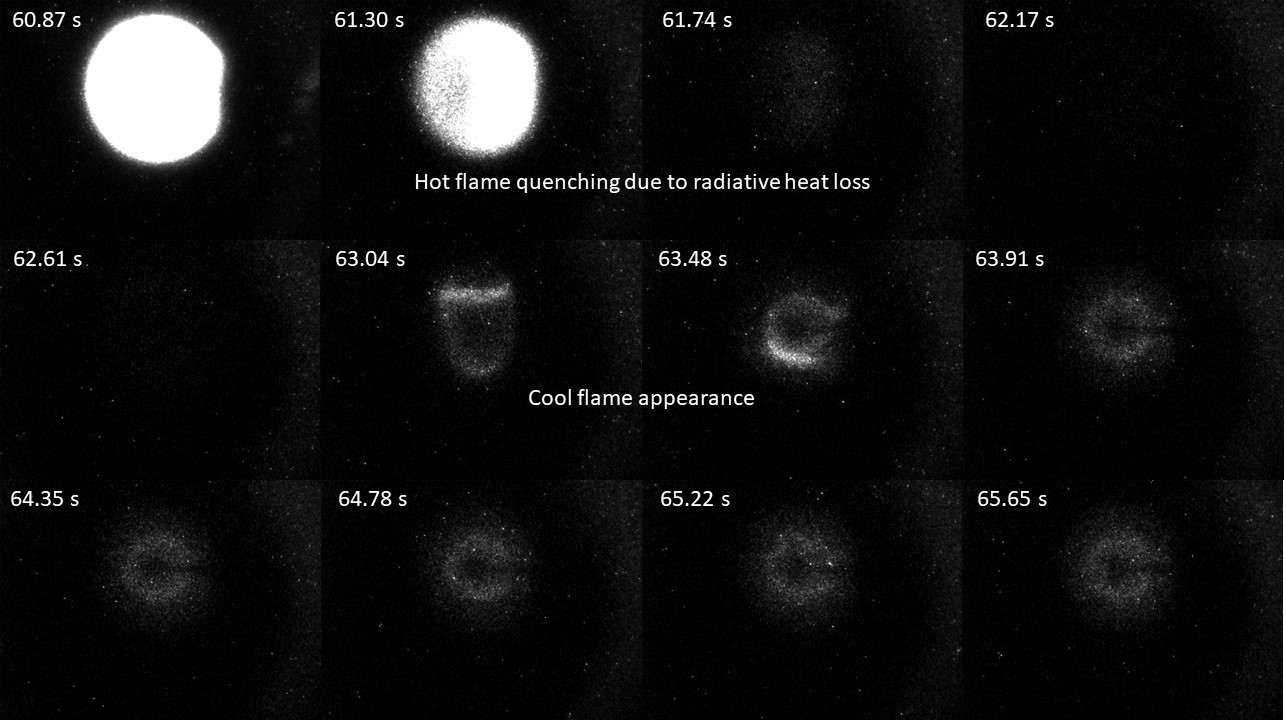

Since cool flames give off little heat or light, they were too faint to be visible in real time during space station testing. The research team uncovered the presence of three cool flames in the data on thermal radiation and burner temperature measurements after the hot flames were quenched.

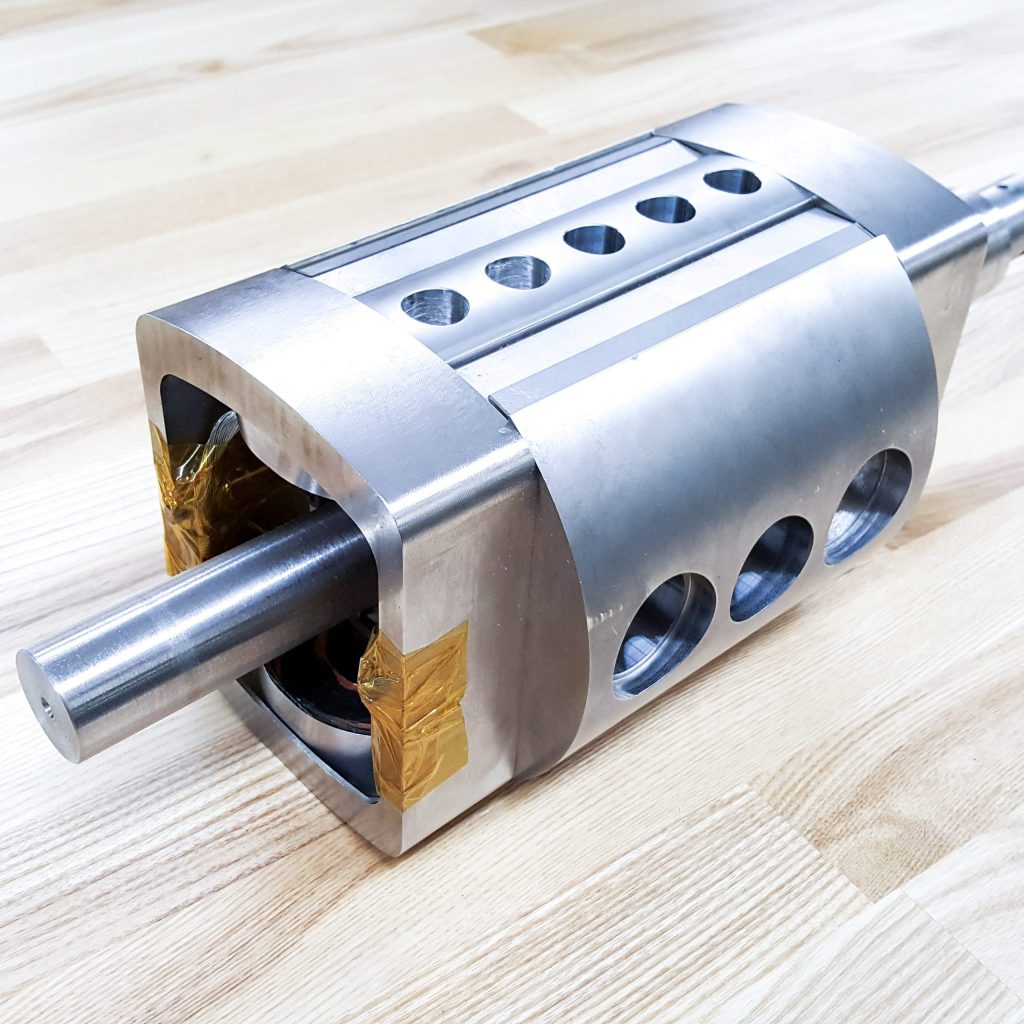

“This is a significant advance in the understanding of cool flames, and we are excited to see these experiment results,” says Dietrich. “The unique geometry and hardware allow Sunderland and his team to study the structure and limits of cool flames in more detail than was possible in earlier station experiments.”

An intensified camera filtered to look for the very faint emissions of a cool flame produced the flame images above. As expected, the cool flame was much smaller than the hot flame. The sequence shows the quenching of the hot flame, followed by a comparatively dark period lasting roughly a second, after which the cool flame becomes evident.

“What used to be a theoretical possibility is now an experimental reality,” says FLEX co-principal investigator Vedha Nayagam. “I am confident that these initial observations will lead to further experimental explorations of the boundaries of cool flame regimes.”