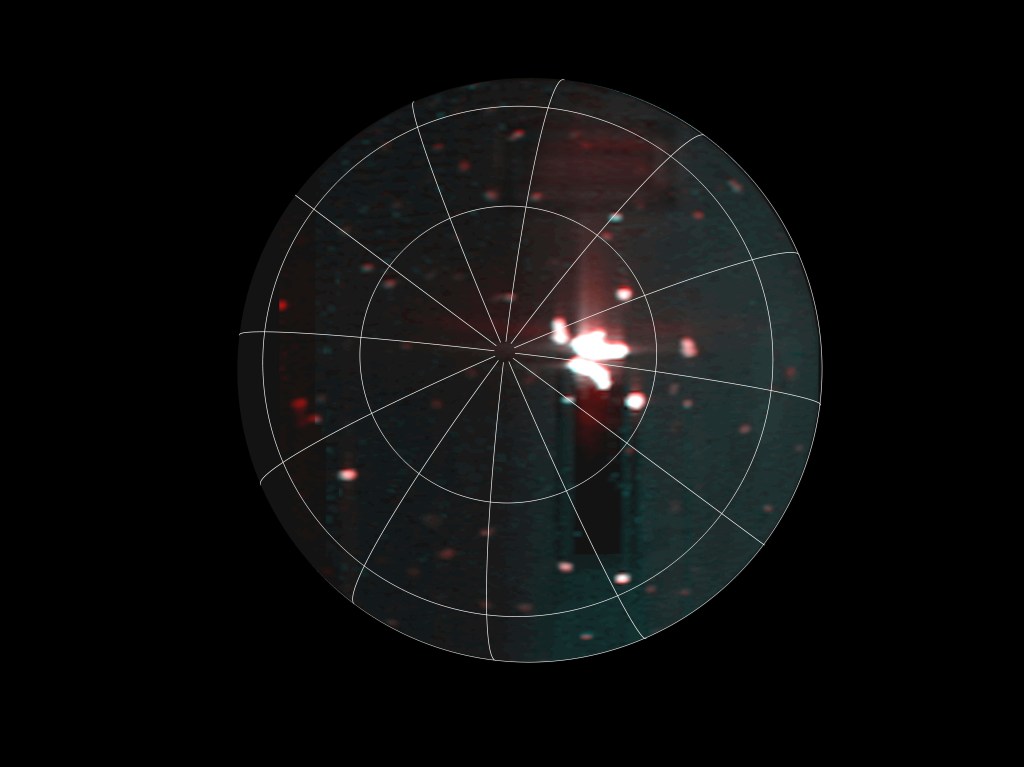

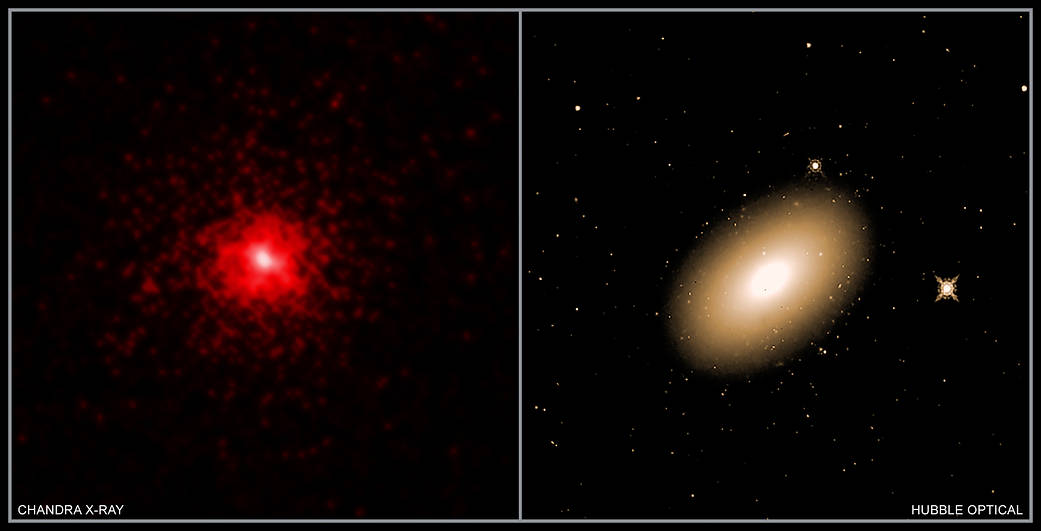

Isolated for billions of years, a galaxy with more dark matter packed into its core than expected has been identified by astronomers using data from NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory.

The galaxy, known as Markarian 1216 (abbreviated as Mrk 1216), contains stars that are within 10% the age of the universe – that is, almost as old as the universe itself. Scientists have found that it has gone through a different evolution than typical galaxies, both in terms of its stars and the invisible dark matter that, through gravity, holds the galaxy together. Dark matter accounts for about 85% of the matter in the universe, although it has only been detected indirectly.

Mrk 1216 belongs to a family of elliptically shaped galaxies that are more densely packed with stars in their centers than most other galaxies. Astronomers think they have descended from reddish, compact galaxies called “red nuggets” that formed about a billion years after the big bang, but then stalled in their growth about 10 billion years ago.

If this explanation is correct, then the dark matter in Mark 1216 and its galactic cousins should also be tightly packed. To test this idea for the first time, a pair of astronomers studied the X-ray brightness and temperature of hot gas at different distances from Mrk 1216’s center, so they could “weigh” how much dark matter exists in the middle of the galaxy.

“When we compared the Chandra data to our computer models, we found a much stronger concentration of dark matter was required than we find in other galaxies of similar total mass,” said David Buote of the University of California at Irvine. “This tells us the history of Mrk 1216 is very different from the typical galaxy. Essentially all of its stars and dark matter was assembled long ago with little added in the past 10 billion years.”

According to the new study, a halo, or fuzzy sphere, of dark matter formed around the center of Mrk 1216 about 3 or 4 billion years after the big bang. This halo is expected to have extended over a larger region than the stars in the galaxy. The formation of such a red nugget galaxy was typical for a wide range of elliptical galaxies seen today. However, unlike Mrk 1216, most giant elliptical galaxies continued to gradually grow in size when smaller galaxies merged with them over cosmic time.

“The old ages and dense concentration of the stars in compact elliptical galaxies like Mrk 1216 seen relatively nearby provided the first key evidence that they are the descendants of the red nuggets seen at great distances”, said co-author Aaron Barth, also of the University of California at Irvine. “We think the compact size of the dark matter halo seen here clinches the case.”

Previously, astronomers estimated that the supermassive black hole in Mrk 1216 is more massive than expected for a galaxy of its mass. This most recent study, however, concluded that the black hole is likely to weigh less than about 4 billion times the mass of the Sun. That sounds like a lot, but it may not be unusually massive for a galaxy as large as Mrk 1216.

The authors also searched for signs of outbursts from the supermassive black hole in the center of the galaxy. They saw hints of cavities in the hot gas similar to those observed in other massive galaxies and galaxy clusters like Perseus, but more data are needed to confirm their presence.

The Mrk 1216 data also provide useful information about dark matter. Because dark matter has never been directly observed, some scientists question whether it exists at all. In the study, Buote and Barth interpreted the Chandra data using both standard, “Newtonian” models of gravity and an alternative theory known as modified Newtonian dynamics, or “MOND” designed to remove the need for dark matter in typical galaxies. The results showed that both theories of gravity required about the same extraordinary amount of dark matter in the center of Mrk 1216, effectively removing the need for the MOND explanation.

“In the future we hope to go a step further and study the nature of dark matter,” said Buote. “The dense accumulation of dark matter in the middle of Mrk 1216 may provide an interesting test for non-standard theories that predict less centrally concentrated dark matter, such as for dark matter particles that interact with each other by an additional means other than gravity.”

A paper describing these results appeared in the May 29th issue of The Astrophysical Journal and is available online. NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama, manages the Chandra program for NASA’s Science Mission Directorate in Washington. The Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory in Cambridge, Massachusetts, controls Chandra’s science and flight operations.

Image credit: X-ray: NASA/CXC/Univ. of CA Irvine/D. Buote; Optical: NASA/STScI

Read more from NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory.

For more Chandra images, multimedia and related materials, visit: