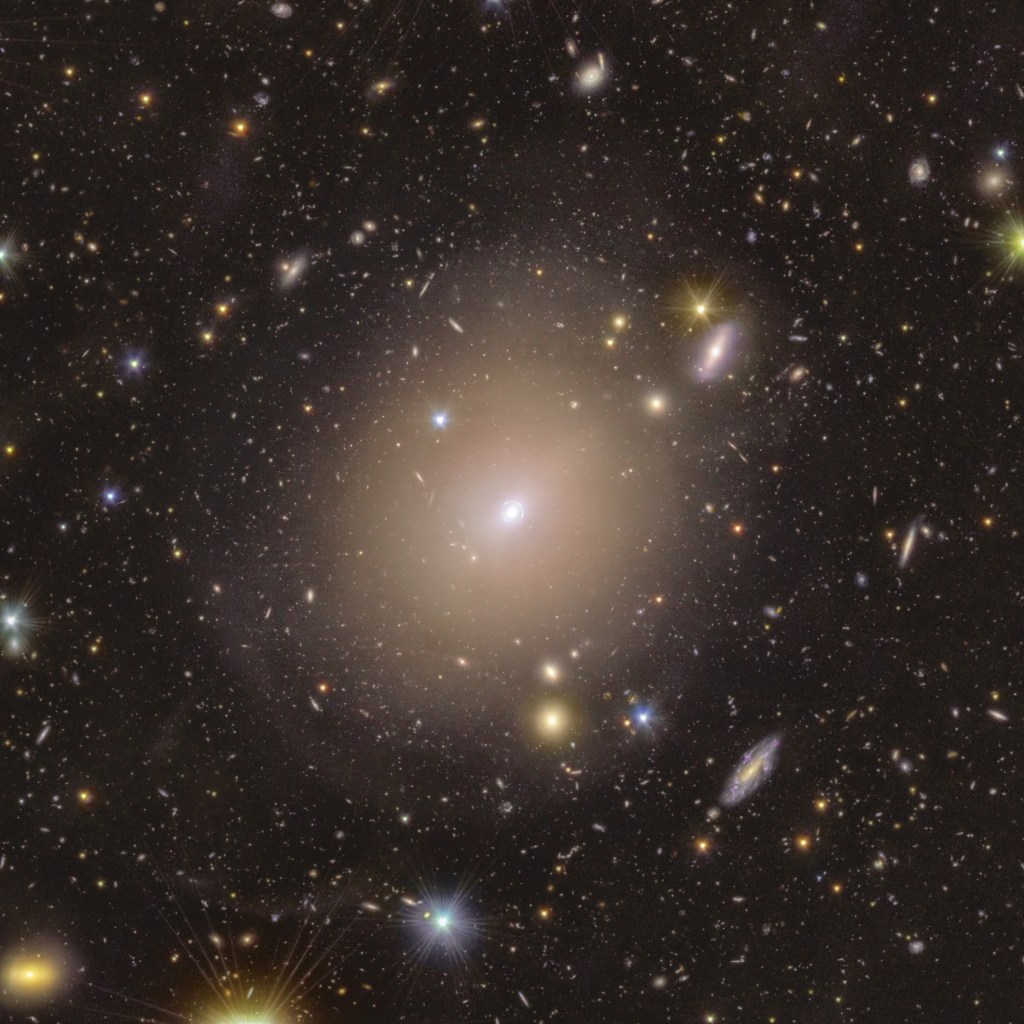

Galaxy clusters are often described by superlatives. After all, they are huge conglomerations of galaxies, hot gas, and dark matter and represent the largest structures in the Universe held together by gravity.

Galaxy clusters tend to be poor at producing new stars in their centers. They generally have one giant galaxy in their middle that forms stars at a rate significantly slower than most galaxies – including our Milky Way. The central galaxy contains a supermassive black hole roughly a thousand times more massive than the one at the center of our galaxy. Without heating by outbursts from this black hole, the copious amounts of hot gas found in the central galaxy should cool, allowing stars to form at a high clip. It is thought that the central black hole acts as a thermostat, preventing rapid cooling of surrounding hot gas and impeding star formation.

New data provide more details on how the galaxy cluster SPT-CLJ2344-4243, nicknamed the Phoenix Cluster for the constellation in which it is found, challenges this trend. The cluster has shattered multiple records in the past: In 2012, scientists announced that the Phoenix cluster featured the highest rate of cooling hot gas and star formation ever seen in the center of a galaxy cluster, and is the most powerful producer of X-rays of all known clusters. The rate at which hot gas is cooling in the center of the cluster is also the largest ever observed.

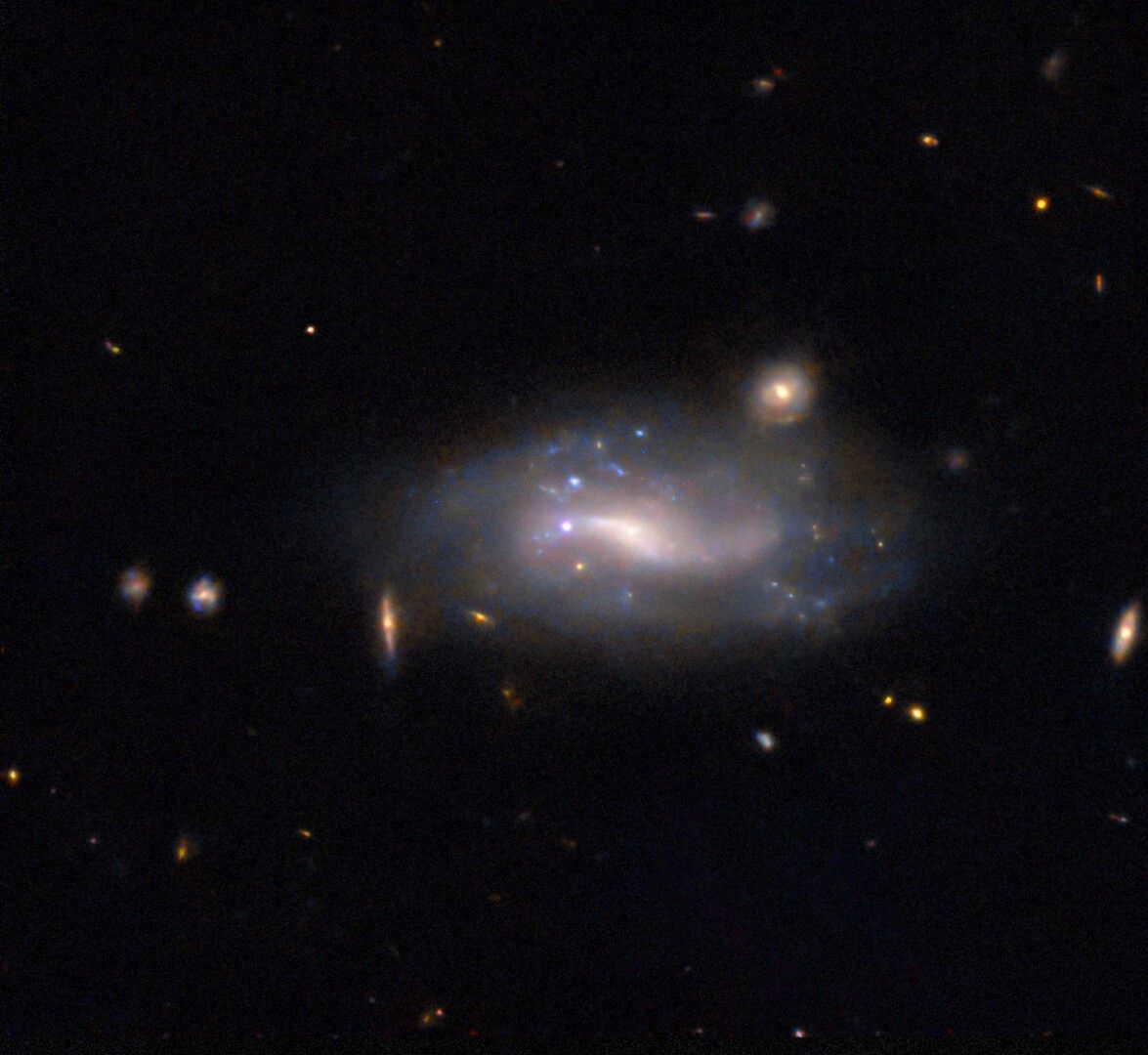

New observations of this galaxy cluster at X-ray, ultraviolet, and optical wavelengths by NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory, the Hubble Space Telescope, and the Clay-Magellan telescope located in Chile, are helping astronomers better understand this remarkable object. Clay-Magellan’s optical data reveal narrow filaments from the center of the cluster where stars are forming. These massive cosmic threads of gas and dust, most of which had never been detected before, extend for 160,000 to 330,000 lights years. This is longer than the entire breadth of the Milky Way galaxy, making them the most extensive filaments ever seen in a galaxy cluster.

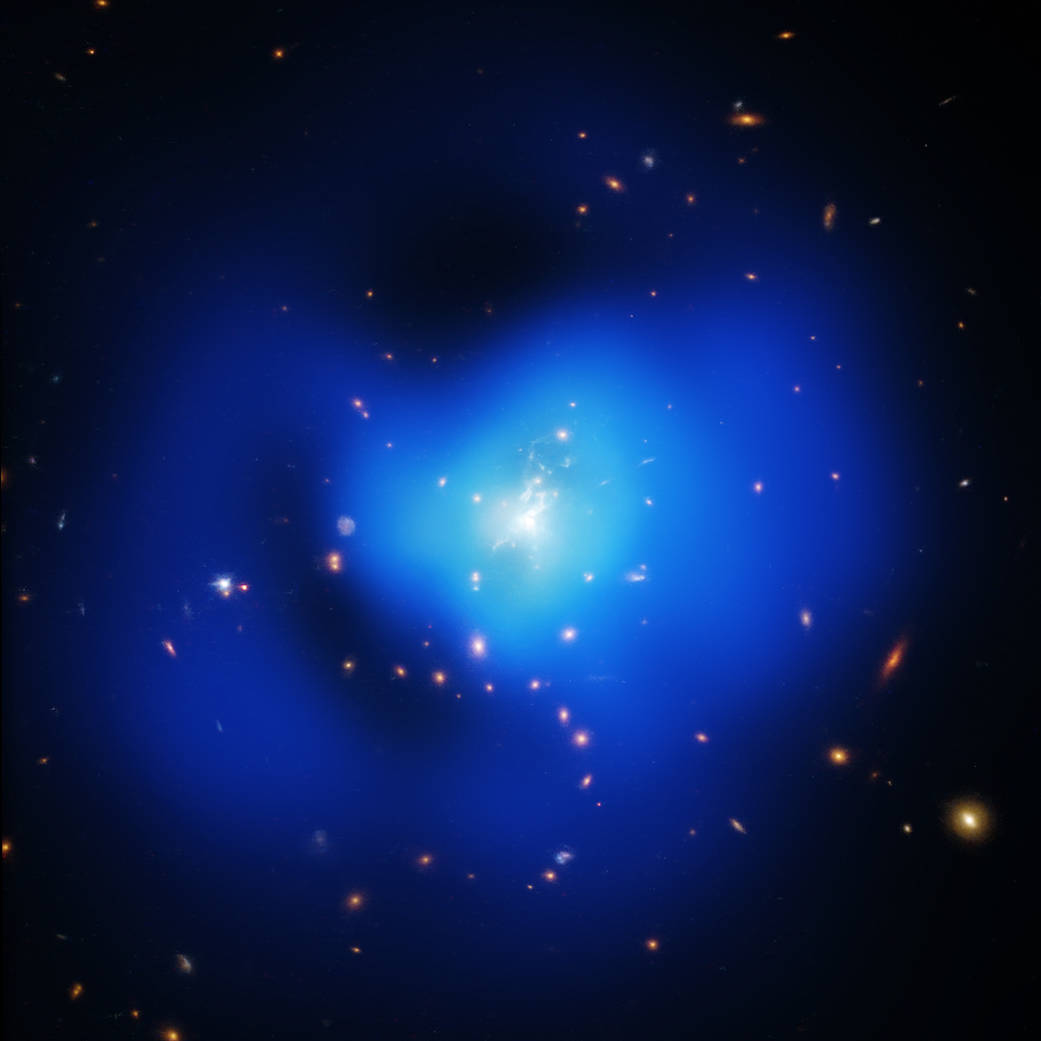

These filaments surround large cavities – regions with greatly reduced X-ray emission – in the hot gas. The X-ray cavities can be seen in this composite image that shows the Chandra X-ray data in blue and optical data from the Hubble Space Telescope (red, green, and blue). For the location of these “inner cavities”, mouse over the image. Astronomers think that the X-ray cavities were carved out of the surrounding gas by powerful jets of high-energy particles emanating from near a supermassive black hole in the central galaxy of the cluster. As matter swirls toward a black hole, an enormous amount of gravitational energy is released. Combined radio and X-ray observations of supermassive black holes in other galaxy clusters have shown that a significant fraction of this energy is released as jets of outbursts that can last millions of years. The observed size of the X-ray cavities indicates that the outburst that produced the cavities in SPT-CLJ2344-4243 SPT- CLJ2344-4243 was one of the most energetic such events ever recorded.

However, the central black hole in the Phoenix cluster is suffering from somewhat of an identity crisis, sharing properties with both “quasars”, very bright objects powered by material falling onto a supermassive black hole, and “radio galaxies” containing jets of energetic particles that glow in radio waves, and are also powered by giant black holes. Half of the energy output from this black hole comes via jets mechanically pushing on the surrounding gas (radio-mode), and the other half from optical, UV and X-radiation originating in an accretion disk (quasar-mode). Astronomers suggest that the black hole may be in the process of flipping between these two states.

X-ray cavities located farther away from the center of the cluster, labeled as “outer cavities”, provide evidence for strong outbursts from the central black hole about a hundred million years ago (neglecting the light travel time to the cluster). This implies that the black hole may have been in a radio mode, with outbursts, about a hundred million years ago, then changed into a quasar mode, and then changed back into a radio mode.

It is thought that rapid cooling may have occurred in between these outbursts, triggering star formation in clumps and filaments throughout the central galaxy at a rate of about 610 solar masses per year. By comparison, only a couple of new stars form every year in our Milky Way galaxy. The extreme properties of the Phoenix cluster system are providing new insights into various astrophysical problems, including the formation of stars, the growth of galaxies and black holes, and the co-evolution of black holes and their environment.

A paper describing these results, led by Michael McDonald (Massachusetts Institute of Technology), has been accepted for publication in The Astrophysical Journal and is available online. NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama, manages the Chandra program for NASA’s Science Mission Directorate in Washington. The Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory in Cambridge, Massachusetts, controls Chandra’s science and flight operations.

Image credit: X-ray: NASA/CXC/MIT/M. McDonald et al.; Optical: NASA/STScI

Read More from NASA’s Chandra X-ray Observatory.

For more Chandra images, multimedia and related materials, visit: